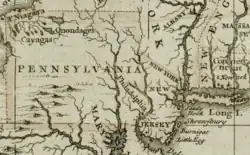

The history of Pittsburgh began with centuries of Native American civilization in the modern Pittsburgh region, known as "Dionde:gâ'" in the Seneca language.[1] Eventually, European explorers encountered the strategic confluence where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio, which leads to the Mississippi River. The area became a battleground when France and Great Britain fought for control in the 1750s. When the British were victorious, the French ceded control of territories east of the Mississippi.

Following American independence in 1783, the village around Fort Pitt continued to grow. The region saw the short-lived Whiskey Rebellion, when farmers rebelled against federal taxes on whiskey. The War of 1812 cut off the supply of British goods, stimulating American manufacture. By 1815, Pittsburgh was producing large quantities of iron, brass, tin, and glass products. By the 1840s, Pittsburgh had grown to be one of the largest cities west of the Allegheny Mountains. Production of steel began in 1875. During the 1877 railway riots it was the site of the most violence and damage in any city affected by the nationwide strikes of that summer. Workers protested against cuts in wages, burning down buildings at the railyards, including 100 train engines and more than 1,000 cars. Forty men were killed, most of them strikers. By 1911, Pittsburgh was producing half the nation's steel.

Pittsburgh was a Republican party stronghold until 1932. The soaring unemployment of the Great Depression, the New Deal relief programs and the rise of powerful labor unions in the 1930s turned the city into a liberal stronghold of the New Deal Coalition under powerful Democratic mayors. In World War II, it was the center of the "Arsenal of Democracy", producing munitions for the Allied war effort as prosperity returned.

Following World War II, Pittsburgh launched a clean air and civic revitalization project known as the "Renaissance." The industrial base continued to expand through the 1960s, but after 1970 foreign competition led to the collapse of the steel industry, with massive layoffs and mill closures. Top corporate headquarters moved out in the 1980s. In 2007 the city lost its status as a major transportation hub. The population of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area is holding steady at 2.4 million; 65% of its residents are of European descent and 35% are minorities.

Native American era

For thousands of years, Native Americans inhabited the region where the Allegheny and the Monongahela join to form the Ohio. Paleo-Indians conducted a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the region perhaps as early as 19,000 years ago. Meadowcroft Rockshelter, an archaeological site west of Pittsburgh, provides evidence that these first Americans lived in the region from that date.[2] During the Adena culture that followed, Mound Builders erected a large Indian Mound at the future site of McKees Rocks, about three miles (5 km) from the head of the Ohio. The Indian Mound, a burial site, was augmented in later years by members of the Hopewell culture.[3]

By 1700 the Haudenosaunee, the Five Nations-based south of the Great Lakes in present-day New York, held dominion over the upper Ohio valley, reserving it for hunting grounds. Other tribes included the Lenape, who had been displaced from eastern Pennsylvania by European settlement, and the Shawnee, who had migrated up from the south.[4] With the arrival of European explorers, these tribes and others had been devastated by infectious diseases from Europe, such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and malaria, to which they had no immunity.[5]

In 1748, when Conrad Weiser visited Logstown, 18 miles (29 km) downriver from Pittsburgh, he counted 789 warriors gathered: the Iroquois included 163 Seneca, 74 Mohawk, 35 Onondaga, 20 Cayuga, and 15 Oneida. Other tribes were 165 Lenape, 162 Shawnee, 100 Wyandot, 40 Tisagechroami, and 15 Mohican.[6]

Shannopin's Town, a Lenape (Delaware) village on the east bank of the Allegheny, was established in the 1720s and was deserted after 1758. The village is believed to have been roughly from where Penn Avenue is today, below the mouth of Two Mile Run, from 30th Street to 39th Street. According to George Croghan, the town was situated on the south bank of the Allegheny, nearly opposite what is now known as Herr's Island, in what is now the Lawrenceville neighborhood in the city of Pittsburgh.[7]: 289

Sawcunk, on the mouth of the Beaver River, was a Lenape settlement and the principal residence of Shingas, a chief of theirs.[8] Chartier's Town was a Shawnee town established in 1734 by Peter Chartier. Kittanning was a Lenape and Shawnee village on the Allegheny, with an estimated 300–400 residents.[9]

Early colonization (1747–1763)

The first Europeans arrived in the 1710s as traders. Michael Bezallion was the first to describe the forks of the Ohio in a manuscript in 1717, and later that year European traders established posts and settlements in the area.[10] Europeans first began to settle in the region in 1748, when the first Ohio Company, a Virginian land speculation company, won a grant of 200,000 acres (800 km2) in the upper Ohio Valley. From a post at present-day Cumberland, Maryland, the company began to construct an 80-mile (130 km) wagon road to the Monongahela River[11] employing a Lenape Indian chief named Nemacolin and a party of settlers headed by Capt. Michael Cresap to begin widening the track into a road. It mostly followed the same route as an existing Native American trail[12] now known as Nemacolin's Trail. The river crossing and flats at Redstone creek, was the earliest point and shortest distance for the descent of a wagon road. Later in the war, the site fortified as Fort Burd (now Brownsville) was one of several possible destinations. Another alternative was the divergent route that became Braddock's Road a few years later through present-day New Stanton. In the event, the colonists did not succeed in turning the path into a wagon road much beyond the Cumberland Narrows pass before they came into conflict with Native Americans. The colonists later mounted a series of expeditions in order to accomplish piecemeal improvements to the track.

The nearby Native American community of Logstown was an important trade and council center in the Ohio Valley.[6] Between June 15 and November 10, 1749, an expedition headed by Celeron de Bienville, a French officer, traveled down the Allegheny and Ohio to bolster the French claim to the region.[12] De Bienville warned away British traders and posted markers claiming the territory.[13]

In 1753, Marquis Duquesne, the Governor of New France, sent another, larger expedition. At present-day Erie, Pennsylvania, an advance party built Fort Presque Isle. They also cut a road through the woods and built Fort Le Boeuf on French Creek, from which it was possible at high water to float to the Allegheny. By summer, an expedition of 1,500 French and Native American men descended the Allegheny. Some wintered at the confluence of French Creek and the Allegheny. The following year, they built Fort Machault at that site.[14]

Alarmed at these French incursions in the Ohio Valley, Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia sent Major George Washington to warn the French to withdraw.[15] Accompanied by Christopher Gist, Washington arrived at the Forks of the Ohio on November 25, 1753.

As I got down before the Canoe, I spent some Time in viewing the Rivers, & the Land in the Fork, which I think extremely well situated for a Fort; as it has the absolute Command of both Rivers. The Land at the Point is 20 or 25 feet (7.6 m) above the common Surface of the Water; & a considerable Bottom of flat well timber'd Land all around it, very convenient for Building.

Proceeding up the Allegheny, Washington presented Dinwiddie's letter to the French commanders first at Venango, and then Fort Le Boeuf. The French officers received Washington with wine and courtesy, but did not withdraw.[15]

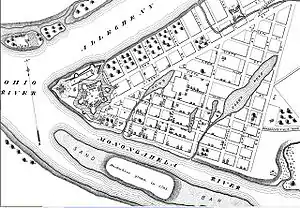

Governor Dinwiddie sent Captain William Trent to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. On February 17, 1754, Trent began construction of the fort, the first European habitation[17] at the site of present-day Pittsburgh. The fort, named Fort Prince George, was only half-built by April 1754, when over 500 French forces arrived and ordered the 40-some colonials back to Virginia. The French tore down the British fortification and constructed Fort Duquesne.[14][15]

Governor Dinwiddie launched another expedition. Colonel Joshua Fry commanded the regiment with his second-in-command, George Washington, leading an advance column. On May 28, 1754, Washington's unit clashed with the French in the Battle of Jumonville Glen, during which 13 French soldiers were killed and 21 were taken prisoner.[18] After the battle, Washington's ally, Seneca chief Tanaghrisson, unexpectedly executed the French commanding officer, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The French pursued Washington and on July 3, 1754, George Washington surrendered following the Battle of Fort Necessity. These frontier actions contributed to the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), or, the Seven Years' War, a global confrontation between Britain and France fought in both hemispheres.[15][19]

In 1755, the Braddock Expedition was launched, accompanied by Virginia militia officer George Washington. Two regiments marched from Fort Cumberland across the Allegheny Mountains and into western Pennsylvania. Following a path Washington surveyed, over 3,000 men built a wagon road 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, that when complete, was the first road to cross the Appalachian Mountains. Braddock's Road, as it was known, blazed the way for the future National Road (US40). The expedition crossed the Monongahela River on July 9, 1755. French troops from Fort Duquesne ambushed Braddock's expedition at Braddock's Field, nine miles (14 km) from Fort Duquesne.[20] In the Battle of the Monongahela, the French inflicted heavy losses on the British, and Braddock was mortally wounded.[21] The surviving British and colonial forces retreated. This left the French and their Native American allies with dominion over the upper Ohio valley.[15]

On September 8, 1756, an expedition of 300 militiamen destroyed the Shawnee and Lenape village of Kittanning, and in the summer of 1758, British Army officer John Forbes began a campaign to capture Fort Duquesne.[21] At the head of 7,000 regular and colonial troops, Forbes built Fort Ligonier and Fort Bedford, from where he cut a wagon road over the Allegheny Mountains, later known as Forbes' Road. On the night of September 13–14, 1758, an advance column under Major James Grant was annihilated in the Battle of Fort Duquesne.[21] The battleground, the high hill east of the Point, was named Grant's Hill in his memory. With this defeat, Forbes decided to wait until spring. But when he heard that the French had lost Fort Frontenac and largely evacuated Fort Duquesne, he planned an immediate attack. Hopelessly outnumbered, the French abandoned and razed Fort Duquesne. Forbes occupied the burned fort on November 25, 1758, and ordered the construction of Fort Pitt, named after British Secretary of State William Pitt the Elder. He also named the settlement between the rivers, "Pittsborough" (see Etymology of Pittsburgh).[11][15] The British garrison at Fort Pitt made substantial improvements to its fortification.[11] The French never attacked Fort Pitt and the war soon ended with the Treaty of Paris and French defeat.[15] They ceded their territories east of the Mississippi River.

Gateway to the West (1763–1799)

In 1760, the first considerable European settlement around Fort Pitt began to grow. Traders and settlers built two groups of houses and cabins, the "lower town," near the fort's ramparts, and the "upper town," along the Monongahela as far as present-day Market Street. In April 1761, a census ordered by Colonel Henry Bouquet and conducted by William Clapham counted 332 people and 104 houses.[21][22]: 148

After Britain's victory in the French and Indian War, increasing dissatisfaction among Native Americans with British policies led to the outbreak of Pontiac's War. The Odawa leader Pontiac launched an offensive against British forts in May 1763. Native American tribes from the Ohio Valley and the Great Lakes overran numerous British forts; one of their most important targets was Fort Pitt. Receiving warning of the coming attack, Captain Simeon Ecuyer, the Swiss officer in command of the garrison, prepared for a siege. He leveled the houses outside the ramparts and ordered all settlers into the fort: 330 men, 104 women, and 196 children sought refuge inside its ramparts.[11] Captain Ecuyer also gathered stores, which included hundreds of barrels of pork and beef. Pontiac's forces attacked the fort on June 22, 1763, and the siege of Fort Pitt lasted for two months.[15] Pontiac's warriors kept up a continuous, though ineffective, fire on it from July 27 through August 1, 1763.[21] They drew off to confront the relieving party under Colonel Bouquet, which defeated them in the Battle of Bushy Run.[21] This victory ensured British dominion over the forks of the Ohio, if not the entire Ohio valley. In 1764 Colonel Bouquet added a redoubt, the Fort Pitt Blockhouse, which still stands, the sole remaining structure from Fort Pitt and the oldest authenticated building west of the Allegheny Mountains.[15]

The Iroquois signed the Fort Stanwix Treaty of 1768, ceding the lands south of the Ohio to the British Crown.[21] European expansion into the upper Ohio valley increased. An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 families settled in western Pennsylvania between 1768 and 1770. Of these settlers, about a third were English-American, another third were Scotch-Irish, and the rest were Welsh, German and others.[23] These groups tended to settle together in small farming communities, but often their households were not within hailing distance. The life of a settler family was one of relentless hard work: clearing the forest, stumping the fields, building cabins and barns, planting, weeding, and harvesting. In addition, almost everything was manufactured by hand, including furniture, tools, candles, buttons, and needles.[23] Settlers had to deal with harsh winters, and with snakes, black bears, mountain lions, and timber wolves. Because of the fear of raids by Native Americans, the settlers often built their cabins near, or even on top of, springs, to ensure access to water. They also built blockhouses, where neighbors would rally during conflicts.[4]

Increasing violence, especially by the Shawnee, Miami, and Wyandot tribes, led to Dunmore's War in 1774. Conflict with Native Americans continued throughout the Revolutionary War, as some hoped that the war would end with expulsion of the settlers from their territory. In 1777, Fort Pitt became a United States fort, when Brigadier General Edward Hand took command. In 1779, Colonel Daniel Brodhead led 600 men from Fort Pitt to destroy Seneca villages along the upper Allegheny.[4]

With the war still ongoing, in 1780 Virginia and Pennsylvania came to an agreement on their mutual borders, creating the state lines known today and determining finally that the jurisdiction of Pittsburgh region was Pennsylvanian. In 1783, the Revolutionary War ended, which also brought at least a temporary cessation of border warfare. In the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois ceded the land north of the Purchase Line to Pennsylvania.[4]

After the Revolution, the village of Pittsburgh continued to grow. One of its earliest industries was boat building. Flatboats could be used to carry large numbers of pioneers and goods downriver, while keelboats were capable of traveling upriver.[24]

The village began to develop vital institutions. Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a Pittsburgh resident and state legislator, introduced a bill that resulted in a gift deed of land and a charter for the Pittsburgh Academy on February 28, 1787. The academy later developed as the University of Western Pennsylvania (1819) and since 1908 has been known as the University of Pittsburgh.[25]

Many farmers distilled their corn harvest into whiskey, increasing its value while lowering its transportation costs. At that time, whiskey was used as a form of currency on the frontier. When the federal government imposed an excise tax on whiskey, Western Pennsylvania farmers felt victimized, leading to the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Farmers from the region rallied at Braddock's Field and marched on Pittsburgh. The short-lived rebellion was put down, however, when President George Washington sent in militias from several states.[20]

The town continued to grow in manufacturing capability. In 1792, the boatyards in Pittsburgh built a sloop, Western Experiment.[26] During the next decades, the yards produced other large boats. By the 19th century, they were building ocean-going vessels that shipped goods as far as Europe. In 1794, the town's first courthouse was built; it was a wooden structure on Market Square.[11] In 1797, the manufacture of glass began.[27]

| Year | City Population[11][21][28][29]: 80 [30] |

|---|---|

| 1761 | 332 |

| 1796 | 1,395 |

| 1800 | 1,565 |

Iron City (1800–1859)

Commerce continued to be an essential part of the economy of early Pittsburgh, but increasingly, manufacture began to grow in importance. Pittsburgh was located in the middle of one of the most productive coalfields in the country; the region was also rich in petroleum, natural gas, lumber, and farm goods. Blacksmiths forged iron implements, from horse shoes to nails. By 1800, the town, with a population of 1,565 persons, had over 60 shops, including general stores, bakeries, and hat and shoe shops.[11]

The 1810s were a critical decade in Pittsburgh's growth. In 1811, the first steamboat was built in Pittsburgh. Increasingly, commerce would also flow upriver. The War of 1812 catalyzed growth of the Iron City. The war with Britain, the manufacturing center of the world, cut off the supply of British goods, stimulating American manufacture.[11] In addition, the British blockade of the American coast increased inland trade, so that goods flowed through Pittsburgh from all four directions. By 1815, Pittsburgh was producing $764K in iron; $249K in brass and tin, and $235K in glass products.[11] When, on March 18, 1816, Pittsburgh was incorporated as a city, it had already taken on some of its defining characteristics: commerce, manufacture, and a constant cloud of coal dust.[32]

Other emerging towns challenged Pittsburgh. In 1818, the first segment of the National Road was completed, from Baltimore to Wheeling, bypassing Pittsburgh. This threatened to render the town less essential in east–west commerce. In the coming decade, however, many improvements were made to the transportation infrastructure. In 1818, the region's first river bridge, the Smithfield Street Bridge, opened, the first step in developing the "City of bridges" over its two rivers. On October 1, 1840, the original Pennsylvania Turnpike was completed, connecting Pittsburgh and the eastern port city of Philadelphia. In 1834, the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal was completed, making Pittsburgh part of a transportation system that included rivers, roads, and canals.[27]

Manufacture continued to grow. In 1835, McClurg, Wade and Co. built the first locomotive west of the Alleghenies. Already, Pittsburgh was capable of manufacturing the most essential machines of its age. By the 1840s, Pittsburgh was one of the largest cities west of the mountains. In 1841, the Second Court House, on Grant's Hill, was completed. Made from polished gray sandstone, the court house had a rotunda 60 feet (18 m) in diameter and 80 feet (24 m) high.[33]

Like many burgeoning cities of its day, Pittsburgh's growth outstripped some of its necessary infrastructure, such as a water supply with dependable pressure.[34] Because of this, on April 10, 1845, a great fire burned out of control, destroying over a thousand buildings and causing $9M in damages.[31] As the city rebuilt, the age of rails arrived. In 1851, the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad began service between Cleveland and Allegheny City (present-day North Side).[27] In 1854, the Pennsylvania Railroad began service between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Despite many challenges, Pittsburgh had grown into an industrial powerhouse. An 1857 article provided a snapshot of the Iron City:[31]

- 939 factories in Pittsburgh and Allegheny City

- employing more than 10K workers

- producing almost $12M in goods

- using 400 steam engines

- Total coal consumed — 22M bushels

- Total iron consumed — 127K tons

- In steam tonnage, third busiest port in the nation, surpassed only by New York City and New Orleans.

| Year | City Population | City Rank[35] |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1,565 | NA |

| 1810 | 4,768 | 31 |

| 1820 | 7,248 | 23 |

| 1830 | 12,568 | 17 |

| 1840 | 21,115 | 17 |

| 1850 | 46,601 | 13 |

| 1860 | 49,221 | 17 |

Steel City (1859–1946)

The iron and steel industry developed rapidly after 1830 and became one of the dominant factors in industrial America by the 1860s.

Scots Irish leadership

Ingham (1978) examined the leadership of the industry in its most important center, Pittsburgh, as well as smaller cities. He concludes that the leadership of the iron and steel industry nationwide was "largely Scotch Irish". Ingham finds that the Scotch Irish held together cohesively throughout the 19th century and "developed their own sense of uniqueness."[36]

New immigrants after 1800 made Pittsburgh a major Scotch-Irish stronghold. For example, Thomas Mellon (b. Ulster 1813–1908) left northern Ireland in 1823 for the United States. He founded the powerful Mellon family, which played a central role in banking and industries such as aluminum and oil. As Barnhisel (2005) finds, industrialists such as James Laughlin (b. Ulster 1806–1882) of Jones and Laughlin Steel Company comprised the "Scots-Irish Presbyterian ruling stratum of Pittsburgh society."[37]

Technology

In 1859, the Clinton and Soho iron furnaces introduced coke-fire smelting to the region. The American Civil War boosted the city's economy with increased production of iron and armaments, especially at the Allegheny Arsenal and the Fort Pitt Foundry.[33] Arms manufacture included iron-clad warships and the world's first 21" gun.[38] By war's end, over one-half of the steel and more than one-third of all U.S. glass was produced in Pittsburgh. A milestone in steel production was achieved in 1875, when the Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock began to make steel rail using the new Bessemer process.[39]

Industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew W. Mellon, and Charles M. Schwab built their fortunes in Pittsburgh. Also based in Pittsburgh was George Westinghouse, credited with such advancements as the air brake and founder of over 60 companies, including Westinghouse Air and Brake Company (1869), Union Switch & Signal (1881), and Westinghouse Electric Company (1886).[40] Banks played a key role in Pittsburgh's development as these industrialists sought massive loans to upgrade plants, integrate industries and fund technological advances. For example, T. Mellon & Sons Bank, founded in 1869, helped to finance an aluminum reduction company that became Alcoa.[39]

Ingham (1991) shows how small, independent iron and steel manufacturers survived and prospered from the 1870s through the 1950s, despite competition from much larger, standardized production firms. These smaller firms were built on a culture that valued local markets and the beneficial role of business in the local community. Small firms concentrated on specialized products, particularly structural steel, where the economies of scale of larger firms were no advantage. They embraced technological change more cautiously than larger firms. They also had less antagonistic relations with workers and employed a higher percentage of highly skilled workers than their mass-production counterparts.[41]

Geography of industrialization

Beginning in the 1870s, entrepreneurs transformed the economy from small, craft-organized factories located inside the city limits to a large integrated industrial region stretching 50 miles across Allegheny County. The new industrial Pittsburgh was based on integrated mills, mass production, and modern management organization in steel and other industries. Many manufacturers searched for large sites with railroad and river accessibility. They purchased land, designed modern plants, and sometimes built towns for workers. Other firms bought into new communities that began as speculative industrial real estate ventures. Some owners removed their plants from the central city's labor unions to exert greater control over workers. The region's rugged topography and dispersed natural resources of coal and gas accentuated this dispersal. The rapid growth of steel, glass, railroad equipment, and coke industries resulted in both large mass-production plants and numerous smaller firms. As capital deepened and interdependence grew, participants multiplied, economies accrued, the division of labor increased, and localized production systems formed around these industries. Transportation, capital, labor markets, and the division of labor in production bound the scattered industrial plants and communities into a sprawling metropolitan district. By 1910 the Pittsburgh district was a complex urban landscape with a dominant central city, surrounded by proximate residential communities, mill towns, satellite cities, and hundreds of mining towns.[42]

Representative of the new industrial suburbs was the model town of Vandergrift, according to Mosher (1995). Caught up in a dramatic round of industrial restructuring and labor tension, Pittsburgh steelmaker George McMurtry hired Frederick Law Olmsted's landscape architectural firm in 1895 to design Vandergrift as a model town. McMurtry believed in what was later known as welfare capitalism, with the company going beyond paychecks to provide for the social needs of the workers; he believed that a benign physical environment made for happier and more productive workers. A strike and lockout at McMurtry's steelworks in Apollo, Pennsylvania, prompted him to build the new town. Wanting a loyal workforce, he developed a town agenda that drew upon environmentalism as well as popular attitudes toward capital's treatment of labor. The Olmsted firm translated this agenda into an urban design that included a unique combination of social reform, comprehensive infrastructure planning, and private homeownership principles. The rates of homeownership and cordial relationships between the steel company and Vandergrift residents fostered loyalty among McMurtry's skilled workers and led to McMurtry's greatest success. In 1901 he used Vandergrift's worker-residents to break the first major strike against the United States Steel Corporation.[43]

Machine politics

Christopher Magee and William Flinn operated powerful Republican machines that controlled local politics after 1880. They were business owners and favored business interests. Flinn was a leader of the Progressive movement statewide and supported Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 election.[44]

Germans

During the mid-19th century, Pittsburgh witnessed a dramatic influx of German immigrants, including a brick mason whose son, Henry J. Heinz, founded the H.J. Heinz Company in 1869. Heinz was at the forefront of reform efforts to improve food purity, working conditions, hours, and wages,[45] but the company bitterly opposed the formation of an independent labor union.[46]

Labor unions

As a manufacturing center, Pittsburgh also became an arena for intense labor strife. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, Pittsburgh workers protested and had massive demonstrations that erupted into widespread violence, known as the Pittsburgh Railway Riots.[47] Militia and federal troops were called to the city to suppress the strike. Forty men died, most of them workers, and more than 40 buildings were burned down, including the Union Depot of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Strikers also burned and destroyed rolling stock: more than 100 train engines and 1000 railcars were destroyed. It was the city with the most violence of any affected by the strikes.

In 1892, a confrontation in the steel industry resulted in 10 deaths (3 detectives, 7 workers) when Carnegie Steel Company's manager Henry Clay Frick sent in Pinkertons to break the Homestead Strike. Labor strife continued into the years of the Great Depression, as workers sought to protect their jobs and improve working conditions. Unions organized H.J. Heinz workers, with the assistance of the Catholic Radical Alliance.

Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie, an immigrant from Scotland, a former Pennsylvania Railroad executive turned steel magnate, founded the Carnegie Steel Company. He proceeded to play a key role in the development of the U.S. steel industry. He became a philanthropist: in 1890, he established the first Carnegie Library, in a program to establish libraries in numerous cities and towns by the incentive of matching funds. In 1895, he founded the Carnegie Institute. In 1901, as the U.S. Steel Corporation formed, he sold his mills to J.P. Morgan for $250 million, making him one of the world's richest men. Carnegie once wrote that a man who dies rich, dies disgraced.[48] He devoted the rest of his life to public service, establishing libraries, trusts, and foundations. In Pittsburgh, he founded the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.[39]

The third (and present) Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail was completed in 1886. In 1890, trolleys began operations.[27] In 1907, Pittsburgh annexed Allegheny City, which is now known as the North Shore.[27]

.jpg.webp)

Early 20th century

By 1911, Pittsburgh had grown into an industrial and commercial powerhouse:[21]

- Nexus of a vast railway system, with freight yards capable of handling 60K cars

- 27.2 miles (43.8 km) of harbor

- Yearly river traffic in excess of 9M tons

- Value of factory products more than $211M (with Allegheny City)

- Allegheny county produced, as percentage of national output, about:

- 24% of the pig iron

- 34% of the Bessemer steel

- 44% of the open hearth steel

- 53% of the crucible steel

- 24% of the steel rails

- 59% of the structural shapes

Prohibition

During the Prohibition era, 1920 to 1933, Pittsburgh was a hotbed of bootlegging and illicit alcohol consumption.[49][50] Several factors fed into resistance to Prohibition, including a large immigrant population, anti-establishment animosity dating to the Whiskey Rebellion, fragmented local government, and pervasive corruption.[50] The Pittsburgh crime family controlled significant portions of the illegal alcohol trade.

During that time, Prohibition Administrator John Pennington and his federal agents engaged in 15,000 raids, arrested over 18,000 people and closed down over 3,000 distilleries, 16 regular breweries, and 400 'wildcat' breweries.[50][51] Even the term "Speakeasy," meaning an illegal drinking establishment, is said to have been coined at the Blind Pig in nearby McKeesport, Pennsylvania.[50][52]

The last distillery in Pittsburgh, Joseph S. Finch's distillery, located at South Second and McKean streets, closed in the 1920s.[53] In 2012, Wigle Whiskey opened, becoming the first since the closure of Finch's distillery.[53]

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette produced a large web feature on this period in the city's history.[54]

Environment

During the late 19th century, city leaders debated the responsibility and expense of creating a waterworks system and disposal of sewage. Downstream users complained about Pittsburgh's dumping of sewage into the Ohio River. Allegheny County cities did not stop discharging raw sewage into rivers until 1939. Pittsburgh's smoke pollution, seen in the 1890s as a sign of prosperity, was recognized as a problem in the Progressive Era and was cleared up in the 1930s–1940s. Steel plants deposited mountains of slag until 1972, especially in Nine Mile Run Valley.[55]

In November 1927, 28 people were killed and hundreds were wounded in an explosion of a gas tank.[56]

To escape the soot of the city, many of the wealthy lived in the Shadyside and East End neighborhoods, a few miles east of downtown. Fifth Avenue was dubbed "Millionaire's Row" because of the many mansions lining the street.

On March 17 and 18, 1936, Pittsburgh suffered the worst flood in its history, with flood levels peaking at 46 feet. This catastrophe killed 69 victims, destroyed thousands of buildings, caused $3B (2006 dollars) in damages, and put more than 60,000 steelworkers out of work.[57]

High culture

Oakland became the city's predominant cultural and educational center, including three universities, multiple museums, a library, a music hall, and a botanical conservatory. Oakland's University of Pittsburgh erected what today is still the world's fourth-tallest educational building, the 42-story Cathedral of Learning.[58] It towered over Forbes Field, where the Pittsburgh Pirates played from 1909 to 1970.[39]

New immigrants and migrants

Between 1870 and 1920, the population of Pittsburgh grew almost sevenfold, with a large number of European immigrants arriving to the city. New arrivals continue to come from Britain, Ireland, and Germany, but the most popular sources after 1870 were poor rural areas in southern and eastern Europe, including Italy, the Balkans, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Empire. Unskilled immigrants found jobs in construction, mining, steel mills and factories. They introduced new traditions, languages, and cultures to the city, creating a diversified society as a result. Ethnic neighborhoods developed in working-class areas and were built on densely populated hillsides and valleys, such as South Side, Polish Hill, Bloomfield, and Squirrel Hill, home to 28% of the city's almost 21,000 Jewish households.[59] The Strip District, the city's produce distribution center, still boasts many restaurants and clubs that showcase these multicultural traditions of Pittsburghers.[39]

African Americans

The years 1916–1940 marked the largest migration of African Americans to Pittsburgh during the Great Migration from the rural South to industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest. These migrants came for industrial jobs, education, political and social freedom, and to escape racial oppression and violence in the South. Migrants going to Pittsburgh and surrounding mill towns faced racial discrimination and restricted housing and job opportunities. The black population in Pittsburgh jumped from 6,000 in 1880 to 27,000 in 1910. Many took highly paid, skilled jobs in the steel mills. Pittsburgh's black population increased to 37,700 in 1920 (6.4% of the total) while the black element in Homestead, Rankin, Braddock, and others nearly doubled. They succeeded in building effective community responses that enabled the survival of new communities.[60][61] Historian Joe Trotter explains the decision process:

- Although African-Americans often expressed their views of the Great Migration in biblical terms and received encouragement from northern black newspapers, railroad companies, and industrial labor agents, they also drew upon family and friendship networks to help in the move to Western Pennsylvania. They formed migration clubs, pooled their money, bought tickets at reduced rates, and often moved ingroups. Before they made the decision to move, they gathered information and debated the pros and cons of the process....In barbershops, poolrooms, and grocery stores, in churches, lodge halls, and clubhouses, and in private homes, southern blacks discussed, debated, and decided what was good and what was bad about moving to the urban North.[62]

The newly established Black communities nearly all endured, apart from Johnstown where blacks were expelled in 1923. Joe Trotter explains how the Blacks built new institutions for their new communities in the Pittsburgh area:

- Black churches, fraternal orders, and newspapers (especially the Pittsburgh Courier); organizations such as the NAACP, Urban League, and Garvey Movement; social clubs, restaurants, and baseball teams; hotels, beauty shops, barber shops, and taverns, all proliferated.[63]

The cultural nucleus of Black Pittsburgh was Wylie Avenue in the Hill District. It became an important jazz mecca because jazz greats such as Duke Ellington and Pittsburgh natives Billy Strayhorn and Earl Hines played there. Two of the Negro League's greatest baseball rivals, the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, often competed in the Hill District. The teams dominated the Negro National League in the 1930s and 1940s.[39]

1930s

Pittsburgh was a Republican stronghold starting in the 1880s,[64] and the Republican governments provided jobs and assistance for the new immigrants in return for their votes. But the Great Depression starting in 1929 ruined the GOP in the city. The Democratic victory of 1932 meant an end to Republican patronage jobs and assistance. As the Depression worsened, Pittsburgh ethnics voted heavily for the Democrats, especially in 1934, making the city a stronghold of the New Deal Coalition. By 1936, Democratic programs for relief and jobs, especially the WPA, were so popular with the ethnics that a large majority voted for the Democrats.[65][66]

Joseph Guffey, statewide leader of the Democrats, and his local lieutenant David Lawrence gained control of all federal patronage in Pittsburgh after Roosevelt's landslide victory in 1932 and the election of a Democratic mayor in 1933. Guffey and Lawrence used the New Deal programs to increase their political power and build up a Democratic machine that superseded the decaying Republican machine. Guffey acknowledged that a high rate of people on relief was not only "a challenge" but also "an opportunity." He regarded each relief job as Democratic patronage.[67]

1940s

Pittsburgh was at the center of the "Arsenal of Democracy" that provided steel, aluminum, munitions and machinery for the U.S. during World War II. Pittsburgh's mills contributed 95 million tons of steel to the war effort. The increased production output created a workforce shortage, which resulted in African Americans moving en masse during the Second Great Migration from the South to the city in order to find work.[11]

Postwar

David Lawrence, a Democrat, served as mayor of Pittsburgh from 1946 to 1959 and as Pennsylvania's governor from 1959 to 1963.[68] Lawrence used his political power to transform Pittsburgh's political machine into a modern governmental unit that could run the city well and honestly.[69] In 1946 Lawrence decided to enforce the Smoke Control Ordinance of 1941 because he believed smoke abatement was crucial for the city's future economic development. However, enforcement placed a substantial burden on the city's working-class because smoky bituminous coal was much less expensive than smokeless fuels. One round of protests came from Italian-American organizations, which called for delay in enforcing it. Enforcement raised their cost of living and threatened the jobs of their relatives in nearby bituminous coal mines. Despite dislike of the smoke abatement program, Italian Americans strongly supported the reelection of Lawrence in 1949, in part because many of them were on the city payroll.[70]

| Year | City Population | City Rank[35] |

|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 49,221 | 17 |

| 1870 | 86,076 | 16 |

| 1880 | 156,389 | 12 |

| 1890 | 238,617 | 13 |

| 1900 | 321,616 | 11 |

| 1910 | 533,905 | 8 |

| 1920 | 588,343 | 9 |

| 1930 | 669,817 | 10 |

| 1940 | 671,659 | 10 |

| 1950 | 676,806 | 12 |

Renaissance I (1946–1973)

Rich and productive, Pittsburgh was also the "Smoky City," with smog sometimes so thick that streetlights burned during the day[11] as well as rivers that resembled open sewers. Civic leaders, notably Mayor David L. Lawrence, elected in 1945, Richard K. Mellon, chairman of Mellon Bank and John P. Robin[71][72] began smoke control and urban revitalization, also known as Urban Renewal projects that transformed the city[11] in unforeseen ways.

"Renaissance I" began in 1946. Title One of the Housing Act of 1949 provided the means in which to begin. By 1950, vast swaths of buildings and land near the Point were demolished for Gateway Center. 1953 saw the opening of the (since demolished) Greater Pittsburgh Municipal Airport terminal.[27]

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the lower Hill District, an area inhabited predominantly by poor Blacks, was completely destroyed. Ninety-five acres of the lower Hill District were cleared using eminent domain, forcibly displacing hundreds of small businesses and more than 8,000 people (1,239 black families, 312 white), to make room for a cultural center that included the Civic Arena, which opened in 1961.[73] Other than one apartment building, none of the other buildings planned for the cultural center were ever built.

In the early 1960s, the neighborhood of East Liberty was also included in Renaissance I Urban Renewal plans, with over 125 acres (0.51 km2) of the neighborhood being demolished and replaced with garden apartments, three 20-story public housing apartments, and a convoluted road-way system that circled a pedestrianized shopping district. In the span of just a few years during the mid-1960s, East Liberty became a blighted neighborhood. There were some 575 businesses in East Liberty in 1959, but only 292 in 1970, and just 98 in 1979.

Preservation efforts by the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation, along with community neighborhood groups, resisted the demolition plans. The neighborhoods containing rich architectural heritage, including the Mexican War Streets, Allegheny West, and Manchester, were spared. The center of Allegheny City, with its culturally and socially important buildings, was not as lucky. All of the buildings, with the exception of the Old U.S. Post Office, the Carnegie Library, and Buhl Planetarium were destroyed and replaced with the "pedestrianized" Allegheny Center Mall and apartments.

The city's industrial base continued to grow in the post-war era[74] partly assisted by the area's first agency entirely devoted to industrial development, the RIDC.[75][76] Jones and Laughlin Steel Company expanded its plant on the Southside. H.J. Heinz, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Alcoa, Westinghouse, U.S. Steel and its new division, the Pittsburgh Chemical Company and many other companies also continued robust operations through the 1960s.[11] 1970 marked the completion of the final building projects of Renaissance I: the U.S. Steel Tower and Three Rivers Stadium.[27] In 1974, with the addition of the fountain at the tip of the Golden Triangle, Point State Park was completed.[77] Although air quality was dramatically improved, and Pittsburgh's manufacturing base seemed solid, questions abound about the negative effects Urban Renewal continues to have on the social fabric of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, however, was about to undergo one of its most dramatic transformations.

Like most major cities, Pittsburgh experienced several days of rioting following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. There were no further major riots, although tension remained high in the inner-city black neighborhoods.[78]

Reinvention (1973–present)

During the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. steel industry came under increasing pressure from foreign competition and from American mini-mills that had much lower overhead by using salvaged steel. Manufacture in Germany and Japan was booming. Foreign mills and factories, built with the latest technology, benefited from lower labor costs and powerful government-corporate partnerships, allowing them to capture increasing market shares of steel and steel products. Separately, demand for steel softened due to recessions, the 1973 oil crisis, and increasing use of other materials.[11][79] The era began with the RIDC's "Building on Basics" report in 1974.[80]

Collapse of steel

Free market pressures exposed the U.S. steel industry's own internal problems, which included a now-outdated manufacturing base that had been over-expanded in the 1950s and 1960s, hostile management and labor relationships, the inflexibility of United Steelworkers regarding wage cuts and work-rule reforms, oligarchic management styles, and poor strategic planning by both unions and management. In particular, Pittsburgh faced its own challenges. Local coke and iron ore deposits were depleted, raising material costs. The large mills in the Pittsburgh region also faced competition from newer, more profitable "mini-mills" and non-union mills with lower labor costs.[79]

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the steel industry in Pittsburgh began to implode along with the deindustrialization of the U.S.[81] Following the 1981–1982 recession, for example, the mills laid off 153,000 workers.[79] The steel mills began to shut down. These closures caused a ripple effect, as railroads, mines, and other factories across the region lost business and closed.[82][83] The local economy suffered a depression, marked by high unemployment and underemployment, as laid-off workers took lower-paying, non-union jobs.[84] Pittsburgh suffered as elsewhere in the Rust Belt with a declining population, and like many other U.S. cities, it also saw white flight to the suburbs.[85]

In 1991 the Homestead Works was demolished, replaced in 1999 by The Waterfront shopping mall. As a direct result of the loss of mill employment, the number of people living in Homestead dwindled. By the time of the 2000 census, the borough population was 3,569. The borough began financially recovering in 2002, with the enlarging retail tax base.

Corporations

Top corporate headquarters such as Gulf Oil (1985), Koppers (1987), Westinghouse (1996) and Rockwell International (1989) were bought out by larger firms, with the loss of high paying, white collar headquarters and research personnel (the "brain drain") as well as massive charitable contributions by the "home based" companies to local cultural and educational institutions. At the time of the Gulf Oil merger in 1985 it was the largest buyout in world history involving the company that was No. 7 on the Fortune 500 just six years earlier. Over 1,000 high paying white collar corporate and PhD research jobs were lost in one day.

Today, there are no steel mills within the city limits of Pittsburgh, although manufacture continues at regional mills, such as the Edgar Thomson Works in nearby Braddock.

Higher education

Pittsburgh is home to three universities that are included in most under-graduate and graduate school national rankings, The University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University and Duquesne University. Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh had evolved in the mid-20th century along lines that followed the needs of the heavy industries that financed and directed their development. The collapse of steel put pressure on those two universities to reinvent themselves as research centers in science and technology which acted to pull the regional economy toward high-technology fields.[86] Other regional collegiate institutions include Robert Morris University, Chatham University, Carlow University, Point Park University, La Roche College, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Trinity School for Ministry (an Episcopal seminary) and the Community College of Allegheny County.

Beginning in the 1980s, Pittsburgh's economy shifted from heavy industry to services, medicine, higher education, tourism, banking, corporate headquarters, and high technology. Today, the top two private employers in the city are the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (26,000 employees) and the West Penn Allegheny Health System (13,000 employees).[87][88]

Civic improvements

Despite the economic turmoil, civic improvements continued. In the mid-1970s, Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr. and the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation (Landmarks) wanted to demonstrate that historic preservation could be used to drive economic development without the use of eminent domain or public subsidies. Landmarks acquired the former terminal buildings and yards of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad, a 1-mile (1.6 km) long property at the base of Mt. Washington facing the City of Pittsburgh. In 1976, Landmarks developed the site as a mixed-use historic adaptive reuse development that gave the foundation the opportunity to put its urban planning principles into practice. Aided by an initial generous gift from the Allegheny Foundation in 1976, Landmarks adapted five historic Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad buildings for new uses and added a hotel, a dock for the Gateway Clipper fleet, and parking areas. Now shops, offices, restaurants, and entertainment anchor the historic riverfront site on the south shore of the Monongahela River, opposite the Golden Triangle (Pittsburgh). Station Square is Pittsburgh's premier attraction, generating over 3,500,000 visitors a year. It reflects a $100 million investment from all sources, with the lowest public cost and highest taxpayer return of any major renewal project in the Pittsburgh region since the 1950s. In 1994, Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation sold Station Square in to Forest City Enterprises which created an endowment to help support its restoration efforts and educational programs. Each year the staff and docents of Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation introduce more than 10,000 people – teachers, students, adults, and visitors – to the architectural heritage of the Pittsburgh region and to the value of historic preservation.[89]

During this period, Pittsburgh also became a national model for community development, through the work of activists such as Dorothy Mae Richardson, who founded Neighborhood Housing Services in 1968, an organization that became the model for the nationwide NeighborWorks America. Activists such a Richardson shared the aim of Landmarks to rehabilitate Pittsburgh's existing built landscape rather than to demolish and redevelop.

In 1985, the J & L Steel site on the north side of the Monongahela river was cleared and a publicly subsidized High Technology Center was built. The Pittsburgh Technology Center, home to many major technology companies, is planning major expansion in the area soon.[27] In the 1980s, the "Renaissance II" urban revitalization created numerous new structures, such as PPG Place. In the 1990s, the former sites of the Homestead, Duquesne and South Side J&L mills were cleared.[27] In 1992, the new terminal at Pittsburgh International Airport opened.[27] In 2001, the aging Three Rivers Stadium was replaced by Heinz Field and PNC Park, despite being rejected by voter referendum. In 2010, PPG Paints Arena, replaced the Civic Arena, which at the time was the oldest arena in the National Hockey League.[90]

Also in 1985, Al Michaels revealed to a national TV audience how Pittsburgh had transformed itself from an industrial rust belt city.[91]

Pittsburgh today

Present-day Pittsburgh, with a diversified economy, a low cost of living, and a rich infrastructure for medicine and education and culture, has been ranked as one of the World's Most Livable Cities.[92] Tourism has recently boomed in Pittsburgh with nearly 3,000 new hotel rooms opening since 2004 and holding a consistently higher occupancy than in comparable cities. Medicine has replaced steel as a leading industry.[93] Meanwhile, tech giants such as Apple, Google, IBM Watson, Facebook, and Intel have joined the 1,600 technology firms choosing to operate out of Pittsburgh. As a result of the proximity to CMU's National Robotics Engineering Center (NREC), there has a boom of autonomous vehicles companies. The region has also become a leader in green environmental design, a movement exemplified by the city's convention center. In the last twenty years the region has seen a small but influential group of Asian immigrants, including from the Indian sub-continent. It has been generally considered as the most recovered city from the rust belt. [94]

| Year | City Population | City Rank[35] | Population of the Urbanized Area[95] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 676,806 | 12 | 1,533,000 |

| 1960 | 604,332 | 16 | 1,804,000 |

| 1970 | 540,025 | 24 | 1,846,000 |

| 1980 | 423,938 | 30 | 1,810,000 |

| 1990 | 369,879 | 40 | 1,678,000 |

| 2000 | 334,563 | 51 | 1,753,000 |

| 2010 | 307,484[96] | 61[96] | 1,733,853 (Ranked 27th, between San Antonio and Sacramento)[97] |

Jurisdiction timeline

- Possibly as early as 17,000 BCE, and until approximately 1750 CE, the area was home to numerous Native American groups, including the Lenape and Seneca tribes.

- 1669 Claimed for the French Empire by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.

- 1681 King Charles claims the forks for Pennsylvania with 5 degrees west of the Delaware.

- 1694 Arnout Viele a Dutch trader explores the area.[98]

- 1717 Settled by European traders, primarily Pennsylvanians; dispute occurs between Virginia and Pennsylvania.

- 1727 Joncaire visits with a small French force.

- 1748 Both Pennsylvanian Conrad Weiser visits and the Kingd approves the Ohio Company for Virginia.

- 1749 Frenchman Louis Blainville deCeleron sails by on the Allegheny and Ohio burying lead plates claiming the area for France.

- 1750 Cumberland County Pennsylvania founded, though its jurisdiction is not governable.

- 1753 George Washington visits en route to Fort LeBeouf.

- 1754 French Forces occupy the area and construct Fort Duquesne.

- 1757 Jesuit Father Claude Francis Virot founded Catholic Mission at Beaver.

- 1758 British Forces regain the area and establish Fort Pitt though some dispute over claims between the colonies of Pennsylvania (Cumberland County) and Virginia (Augusta County).

- 1761 Ayr Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.

- 1763 The Proclamation of 1763 grants Quebec rights to all lands west of the Alleghenies and North of the Ohio River.

- 1767 Bedford Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.[99]

- 1770 George Washington visits for Virginia.

- 1771 (March 9) Bedford County, Pennsylvania.[99]

- 1771 (April 16) Pitt Township founded.[100]

- 1773 (February 26) part of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

- 1788 (September 24) part of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

- 1788 (December 16) A new Pitt Township is formed as a division of Allegheny County.[101]

- 1792 (June) Petition for a Pittsburgh Township at the forks.

- 1792 (September 6) Pittsburgh Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

- 1794 (April 22) Pittsburgh borough, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.[102]

- 1816 (March 18) City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

See also

- Timeline of Pittsburgh

- Westinghouse Works, 1904 - series of early films showing working conditions in Westinghouse factories

- List of mayors of Pittsburgh

- List of Pittsburgh neighborhoods

- List of major corporations in Pittsburgh

- University of Pittsburgh

- Pittsburgh Riot

- Pittsburgh Flood of 1936

- History of the Jews in Pittsburgh

References

- ↑ "Glossary of Seneca Words". Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ↑ Shreeve, James. "The Greatest Journey," National Geographic, March 2006, pg. 64.

- ↑ Pitz, Marylynne (May 12, 2001). "Burial Mound to Get Historical Marker". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Sipe, C. Hale, The Indian Wars of Pennsylvania, 1831, Wennawoods Publishing reprint 1999

- ↑ Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650, (1998)

- 1 2 Agnew, Daniel, Myers, Shinkle & Co., Logstown, on the Ohio, 1894. pg. 7.

- ↑ Charles Augustus Hanna, The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Volume 1, Putnam's sons, 1911

- ↑ Buck, The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania, (1939), pg. 30.

- ↑ Course of Study in Geographic, Biographic and Historic Pittsburgh, The Board of Public Education, Pittsburgh, 1921.

- ↑ "Chronology". Historic Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lorant, Stefan (1999). Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City, 5th edition. Derrydale Press. ISBN 0-9674103-0-4.

- 1 2

Commission members: Thomas Lynch Montgomery, Henry Melchior Muhlenberg Richards, John M. Buckalew, George Dallas Albert, Sheldon Reynolds, Jay Gilfillan Weiser; compiled by George Dallas Albert (1916). The frontier forts of western Pennsylvania. Report By the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania: W.S. Ray, state printer. p. 382. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

Note: pp. 382 specifically discusses the 'Hanger' fort (literally in French: "storehouse") (a blockhouse) site on Redstone creek founded in 1754 on the ford; the Dunlap Creek site of Fort Burd is located on the bigger (canoe friendly) stream.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Crumrine, Boyd, L.H. Everts and Co. History of Washington County, Pennsylvania, 1882, pg. 26.

- 1 2 Albert, George (1896). The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania. C. M. Busch.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "A History of the Point". Fort Pitt Museum. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Jackson, Donald (1976). Twohig, Dorothy (ed.). The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1. University Press of Virginia.

- ↑ Wilson, Erasmus; H.R. Cornell; et al., eds. (1898). Standard History of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. p. 58.

- ↑ "History and Culture". Fort Necessity National Battlefield. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ↑ Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-375-70636-4.

- 1 2 The Unwritten History of Braddock's Field (Pennsylvania), editor Geo. H. Lamb, A. M., Nicholson Printing Co., 1917

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Pittsburgh". Encyclopædia. 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Bausman, Joseph Henderson. History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania: And Its Centennial Celebration. Knickerbocker Press, 1904.

- 1 2 Bartlett, Virginia K. (1994). Keeping House, Women's Lives in Western Pennsylvania. Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-5538-5.

- ↑ Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. "Pittsburgh: History". City-Data. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Lynch Starrett, Agnes (2007). Through one hundred and fifty years: the University of Pittsburgh. Kessinger Publishing.

- ↑ Wiley, Richard Taylor (1937). Monongahela, the River and Its Region. The Ziegler Company.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Key Events in Pittsburgh History". WQED Pittsburgh History Site. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Cushing, Thomas (1889). History of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. A. Warner Co., Chicago. p. 621.

- ↑ Chapman, Thomas Jefferson, Old Pittsburgh Days. J. R. Weldin & Company, 1900.

- ↑ "A List of Houses and Inhabitants at Fort Pitt, 14 April, 1761." in Bouquet, H., Kent, D. H., Stevens, S. Kirby., British Library., Pennsylvania Historical Commission., Frontier Forts and Trails Survey. (1940). The papers of Col: Henry Bouquet, vol. 7. Harrisburg: Department of public instruction, Pennsylvania historical commission, pp 103-108

- 1 2 3 4 Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion. Ballou's, Boston. February 21, 1857. ISBN 0-942301-23-4.

- ↑ "Pittsburgh in 1816". Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. 1916. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- 1 2 Boucher, John Newton (1908). A century and a half of Pittsburgh and her people. The Lewis Publishing Company.

- ↑ History of the Allegheny Fire Department. Allegheny Fire Dept. 1895.

- 1 2 3 "Population of the 100 largest cities and other urban places in the united states: 1790 to 1990". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ↑ John Ingham, The Iron Barons (1978) quotes pp 7 and 228.

- ↑ Gregory Barnhisel James Laughlin, New Directions, and the Remaking of Ezra Pound (2005) p. 48.

- ↑ Thurston, George H (1888). Allegheny County's Hundred Years. A. A. Anderson Son, Pittsburgh.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Meislik, Miriam; Galloway, Ed (1999). History of Pittsburgh. Society of American Archivists, Pittsburgh.

- ↑ "Westinghouse, Our Past". Westinghouse. 2007. Archived from the original on May 9, 2004. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ↑ John N. Ingham, "Iron and Steel in the Pittsburgh Region: The Domain of Small Business," Business and Economic History 1991 20: 107–116

- ↑ Edward K. Muller, "Industrial Suburbs and the Growth of Metropolitan Pittsburgh, 1870–1920," Journal of Historical Geography 2001 27(1): 58–73

- ↑ Anne E. Mosher, "'Something Better than the Best': Industrial Restructuring, George McMurtry and the Creation of the Model Industrial Town of Vandergrift, Pennsylvania, 1883–1901," Annals of the Association of American Geographers 1995 85(1): 84–107,

- ↑ Eugene Kaufman, "A Pittsburgh Political Battle Royal of A Half Century Ago." Western Pennsylvania History (1952): 79-84. online on the machine's defeat in 1900-1903.

- ↑ "Heinz Family History". Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Heineman, Kenneth A. (1999). A Catholic New Deal: Religion and Reform in Depression Pittsburgh. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01896-8.

- ↑ Harper's Weekly, Journal of Civilization Vol. XXL, No. 1076 New York, August 11, 1877.

- ↑ Carnegie, Andrew. "The North American Review Volume 0148 Issue 391". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ McGee, Chris (1994). "Prohibition's Failure in Pittsburgh". The Sloping Halls Review, Volume 1, 1994. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Prohibition ended 80 years ago today, but the dry movement never worked here". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 4, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ Comte, Julien (Spring 2010). ""Let the Federal Men Raid": Bootlegging and Prohibition Enforcement in Pittsburgh". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. Project MUSE. 77 (2): 166–192. doi:10.1353/pnh.0.0021. S2CID 143698372. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Munch goes to the Blind Pig". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 30, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Toland, Bill (March 29, 2012). "Pittsburgh gets its first distillery since before Prohibition". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ↑ Mellon, Steve. "Pittsburgh:The Dark Years". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ Joel Tarr, "The Metabolism of the Industrial City: The Case of Pittsburgh," Journal of Urban History 2002 28(5): 511–545

- ↑ Brotzman, W. S. (January 25, 1928). "Damaging Gas Explosion at Pittsburgh, PA" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 55 (11): 500. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1927)55<500a:DGEAPP>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ↑ Mildred Flaherty, The Great Saint Patrick's Day Flood, (The Local History Company, Pittsburgh, PA, 2004)

- ↑ List of tallest educational buildings Accessed 13 August 2017

- ↑ "The 2002 Pittsburgh Jewish Community Study". United Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh. December 2002. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Joe W. Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania." Western Pennsylvania History (1995) 78#4: 153-158 online.

- ↑ Joe W. Trotter, and Eric Ledell Smith, eds. African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives (Penn State Press, 2010).

- ↑ Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania," p 154.

- ↑ Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania," pp 156-57.

- ↑ Between 1884 and 1933, only two Democrats served as mayors of Pittsburgh, Bernard McKenna from 1893 through 1896 and George Guthrie between 1906 and 1909.

- ↑ Stefano Luconi, "The Roosevelt Majority: The Case of Italian Americans in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia," Journal of American Ethnic History 1996 15(2): 32–59

- ↑ Richard C. Keller, Pennsylvania's Little New Deal (1960)

- ↑ Bruce M. Stave, The New Deal and the Last Hurrah: Pittsburgh Machine Politics (1970)

- ↑ Michael P. Weber, Don't Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh's Renaissance Mayor, (1988)

- ↑ Richard Robbins, "David L. Lawrence: The Deft Hand Behind Pittsburgh's – and Pennsylvania's – Politics," Pennsylvania Heritage 2001 27(4): 22–29

- ↑ Stefano Luconi, "The Enforcement of the 1941 Smoke-Control Ordinance and Italian Americans in Pittsburgh," Pennsylvania History 1999 66(4): 580–594

- ↑ "Robin Chosen Head of Industrial Plan", Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, July 30, 1955

- ↑ Copage, Eric V. (July 30, 1955), "John P. Robin, 87; Led the Redevelopment of Downtown Pittsburgh", New York Times, New York, NY, retrieved February 10, 2014

- ↑ "Building the Igloo". Pittsburgh Heritage Project. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Pittsburgh Booms While Rest of U.S. Begins to Slacken". The Evening Independent. March 22, 1949. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ White, William A. (June 26, 1956), "Power Firm Turned Lake Area Into Gigantic Chemical Shore", Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, p. 1

- ↑ "Development group files for charter", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, PA, p. 28, August 4, 1955

- ↑ "History, Point State Park". Pennsylvania State Parks Website. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Alyssa (2013). "A Period of Turmoil: Pittsburgh's April 1968 Riots and Their Aftermath; 39#2". Journal of Urban History. pp. 147–171. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hoerr, John P. (1988). And the Wolf Finally Came: The Decline of the American Steel Industry. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-5398-6.

- ↑ "Area's Economy Reported Strong", Beaver County Times, Beaver, PA, September 23, 1974

- ↑ Toland, Bill (December 23, 2012). "In desperate 1983, there was nowhere for Pittsburgh's economy to go but up". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ Barnes, Tom (December 29, 1989). "'80s Gave City, State Surprise, Shock and Sadness: A Top Rating, a Suicide, a Mayor's Death, Nature's Wrath". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ Wade, Chet (December 27, 1989). "How You View the Decade May Depend On Whether You Kept or Lost Your Job". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ Briem, Christopher (December 23, 2012). "For Pittsburgh a future not reliant on steel was unthinkable ... and unavoidable". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Western PA History: Renaissance City: Corporate Center 1945–present". WQED's Pittsburgh History Teacher's Guide series. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Annette L. Giovengo, "The Historical Roles of Pittsburgh's Research Universities in Regional Economic Development," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 1987 70(3): 257–277

- ↑ "Top Private Employers". Pittsburgh Regional Alliance. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Allegheny Health Network

- ↑ "A Brief History of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation". Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. 2008. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Plan B". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Hopey, Don (October 3, 1985). "Pittsburgh's Image Belies Workforce". The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ↑ Majors, Dan (April 26, 2007). "Pittsburgh rated 'most livable' once again". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- ↑ Gabriel Winant, The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America (Harvard University Press, 2021), focus on Pittsburgh.

- ↑ "Asians Study in Pittsburgh, Then Stay to Start Businesses". Reading Eagle. November 26, 2006.

- ↑ "US Urbanized Areas 1950–1990 Urbanized Area Data". Demographia. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- 1 2 "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places Over 50,000, Ranked by July 1, 2011 Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011". 2011 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. June 2012. Archived from the original (CSV) on August 21, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ "2010 Census Urban Area List". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Early Beaver County Chronology--1600s-1800". Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- 1 2 "Old Bedford County Townships". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Greene County and Its Courts" (PDF). Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ History of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Vol. 2. Chicago: A. Warner & Co. 1889. p. 115.

- ↑ "How to Spell Pittsburgh". Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

Bibliography

- Baldwin, Leland D. Pittsburgh: The Story of a City (U of Pittsburgh Press, 1937) online

- Bauman, John F.; Muller, Edward K. (2006). "Before Renaissance: Planning in Pittsburgh, 1889–1943". University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 331. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- Cannadine, David. Mellon: An American Life (2006), major biography of Thomas Mellon and Andrew Mellon, top financial leaders

- Carson, Carolyn Leonard. Healing Body, Mind, and Spirit: The History of the St. Francis Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Carnegie Mellon U. Press, 1995. 246 pp.

- Couvares, Francis G. (1984). "The Remaking of Pittsburgh: Class and Culture in an Industrializing City 1877–1919". State University of New York Press.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Cowan, Aaron. A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism and Urban Revitalization in the Postwar Rustbelt (2016) compares Cincinnati, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore in the wake of deindustrialization.

- Crowley, Gregory J. The Politics of Place: Contentious Urban Redevelopment in Pittsburgh. (U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2005). 207 pp.

- Devault, Ileen A. Sons and Daughters of Labor: Class and Clerical Work in Turn-of-the-Century Pittsburgh. (Cornell U. Press, 1991). 194 pp.

- Dieterich-Ward, Allen Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. 347pp. online review

- Glasco, Laurence A., ed. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. (U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2004). 422 pp.

- Greenwald, Maurine W. and Margo Anderson, eds. Pittsburgh Surveyed: Social Science and Social Reform in the Early Twentieth Century. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 292 pp.

- Grinder, Robert Dale. " From Insurgency to Efficiency: The Smoke Abatement Campaign in Pittsburgh before World War I." Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (1978) 61#3 pp 187–202.

- Hays, Samuel P., ed. City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1989. 473 pp.

- Heineman, Kenneth J. (1999). "A Catholic New Deal: Religion and Reform in Depression Pittsburgh". Pennsylvania State U. Press. p. 287.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Hinshaw, John. Steel and Steelworkers: Race and Class Struggle in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. State U. of New York Press, 2002. 348 pp.

- Holli, Melvin G., and Jones, Peter d'A., eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980 (Greenwood Press, 1981) short scholarly biographies each of the city's mayors 1820 to 1980. online; see index at p. 410 for list.

- Hoerr, John. And the Wolf Finally Came: The Decline of American Steel. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 689 pp.

- Holt, Michael. Forging a Majority: The Formation of the Republican Party in Pittsburgh, 1848-18 (1969).

- Ingham, John N. Making Iron and Steel: Independent Mills in Pittsburgh, 1820–1920. Ohio State U. Press, 1991. 297 pp.

- Kleinberg, S. J. The Shadow of the Mills: Working-Class Families in Pittsburgh, 1870–1907. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1989. 414 pp.

- Kobus, Kenneth J. City of Steel: How Pittsburgh became the world's steelmaking capital during the Carnegie era (2015) 320pp.

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. 548 pp.

- Lopez, Steven Henry. Reorganizing the Rust Belt: An Inside Study of the American Labor Movement. U. of California Press, 2004. 314 pp.

- Lorant, Stefan. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City, (1964), well written, heavily illustrated popular history

- Lubove, Roy. Twentieth Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change (1969).

- Lubove, Roy. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 2: The Post-Steel Era. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 413 pp. the major scholarly synthesis.

- Mayfield, Loomis. "Voting Fraud in Early Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh." Journal of Interdisciplinary History 24#1 (1993), pp. 59–84 online

- Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie (2006), major scholarly biography. online

- Rishel, Joseph F. Founding Families of Pittsburgh: The Evolution of a Regional Elite, 1760–1910. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. 241 pp.

- Rose, James D. Duquesne and the Rise of Steel Unionism. U. of Illinois Press, 2001. 284 pp.

- Ruck, Rob. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. U. of Illinois Press, 1987. 238 pp.

- Seely, Bruce E., ed. Iron and Steel in the Twentieth Century. Facts on File, 1994. 512 pp.

- Slavishak, Edward Steven. Bodies of Work: Civic Display and Labor in Industrial Pittsburgh (2008)

- Smith, Arthur G. Pittsburgh: Then and Now. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. 336 pp.

- Smith, George David. From Monopoly to Competition: The Transformation of Alcoa, 1888–1986. Cambridge U. Press, 1988. 554 pp.

- Stave, Bruce M. "Pittsburgh and the New Deal," in John Braeman et al. eds. The New Deal: Volume Two – the State and Local Levels (1975) pp 376–406

- Tarr, Joel A., ed. (2003). "Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region". U. of Pittsburgh Press. p. 312. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- Trotter, Joe W., and Jared N. Day. Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh Since World War II (University of Pittsburgh Press; 2010) 328 pages. Draws on journalism, oral histories, and other sources to study the city's black community, including its experience of the city's industrial decline and rebirth.

- Wade, Richard C. The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790–1830. (1959)

- Wall, Joseph. Andrew Carnegie (1970). 1137 pp.; major scholarly biography

- Warren, Kenneth. Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

- Weber, Michael P. Don't Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh's Renaissance Mayor. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 440 pp.

- Winant, Gabriel. The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America (Harvard University Press, 2021), focus on Pittsburgh

Primary sources

- Lubove, Roy, ed. Pittsburgh 1976. 294 pp. short excerpts covering main themes

- Kellogg, Paul Underwood, ed. (1914). The Pittsburgh survey: findings in six volumes. Charities Publication Committee. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

famous in-depth study of society and government

- Thomas, Clarke M. ed. Front-Page Pittsburgh: Two Hundred Years of the Post-Gazette. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. 332 pp. readable copies of key front pages

- The Pittsburgh directory for 1815, Pittsburgh: Printed for James M. Riddle, compiler and publisher, 1815, OCLC 21956933, OL 24166640M

- The Pittsburgh directory for 1819, Pittsburgh: Printed by Butler & Lambdin, 1819, OCLC 30696960, OL 24467282M

- "Pittsburgh", American Advertising Directory, for Manufacturers and Dealers in American Goods, New York: Jocelyn, Darling & Co., 1831, OCLC 1018684

- Harris' Pittsburgh & Allegheny directory, Pittsburgh: Printed by A.A. Anderson, 1839, OCLC 22234968, OL 23302955M

- Harris' business directory of the cities of Pittsburgh & Allegheny, Pittsburgh: Printed by A.A. Anderson, 1844, OL 24349698M

- "Historic Pittsburgh General Text Collection". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

Digital Library, 500 published works from the 19th and early 20th centuries that document Pittsburgh history. The scope of the collection includes poetry, fiction, genealogy and biography. Contains both primary and secondary sources.

External links

- "Historic Pittsburgh". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

Provides historic materials from the University of Pittsburgh's University Library System, the Library & Archives of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania at the Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center, and the Carnegie Museum of Art, including city directories 1815–1945.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - "Pittsburgh History". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

maintained by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

- "Historical interactive maps". Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- "Life in Western Pennsylvania". Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

Contains digitized films and photographs from the Library and Archives of the Senator John Heinz History Center.

- "German Historical Sites in Pittsburgh". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- "The History of Pittsburgh's Skyline". Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- "The Battle of the Monongahela". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- Old photos of Pittsburg(h)

- "Wayward record of Pittsburgh's early years recovered by archivist"