Milwaukee, Wisconsin's history, which includes over 160 years of immigration (of Germans, Irish, French, Yankees, Poles, Blacks and Hispanics), politics (including a strong Socialist movement), and industry (including machines, cheese, and beer), has given it a distinctive heritage.

To 1820

The first recorded inhabitants of the Milwaukee area are the Menominee, Fox, Mascouten, Sauk, Potawatomi, Ojibwe (all Algic/Algonquian peoples) and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) (a Siouan people) Native American tribes. Many of these people had lived around Green Bay[1] before migrating to the Milwaukee area around the time of European immigration.

The name "Milwaukee" comes from an Algonquian word Millioke, meaning "Good", "Beautiful" and "Pleasant Land" (cf. Potawatomi language minwaking, Ojibwe language ominowakiing) or "Gathering place [by the water]" (cf. Potawatomi language manwaking, Ojibwe language omaniwakiing).[2][3]

French missionaries and traders first passed through the area in the late 17th and 18th centuries. French explorer Robert La Salle was most likely the first white man to visit Milwaukee in October 1679.[4] Although La Salle and others visited Milwaukee, prior to the 19th century, Milwaukee was mostly inhabited by Native Americans.

The Natives at Milwaukee tried to control their destiny by participating in all the major wars on the American continent. During the French and Indian War, a group of "Ojibwas and Pottawattamies from the far [Lake] Michigan" (i.e., the area from Milwaukee to Green Bay) joined the French-Canadian Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu at the Battle of the Monongahela.[5] In the American Revolutionary War, the Indians around Milwaukee were some of the few Indians who remained loyal to the American cause throughout the Revolution.[6]

As the 18th century came to a close, the first recorded white fur trader settled in Milwaukee. This was French Canadian Jean Baptiste Mirandeau who along with Jacques Vieau of La Baye (Green Bay), established a fur-trading post near the Menomonee River in 1795. Mirandeau remained all year with Vieau coming every spring with supplies. In 1820 or 1821 Mirandeau died and was the first white to be buried in the city in an Indian cemetery near Broadway and Wisconsin. The post was on the Chicago-Green Bay trail, located on the site of today's Mitchell Park. Vieau married the granddaughter of an Indian chief and had at least twelve children. Vieau's daughter by another woman, Josette, would later marry Solomon Juneau. These links established a Metis population, and by 1820 Milwaukee was essentially a Metis settlement.[7]

1820 to 1849

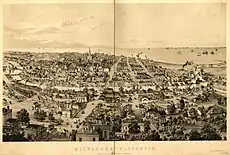

Milwaukee has three "founding fathers": Solomon Juneau, Byron Kilbourn, and George H. Walker. Solomon Juneau, the first of the three to come to the area, arrived in 1818. The French Canadian Juneau married Josette Vieau, daughter of Jacques Vieau, in 1820, and Vieau eventually sold the trading post to his son-in-law and daughter, the "founding mother of Milwaukee." The Juneaus moved the post in 1825 to the eastern bank of the Milwaukee River (between the river and Lake Michigan), where they founded the town called Juneau's Side, or Juneautown. This town soon attracted settlers from the Eastern United States and Europe.

Soon after, Byron Kilbourn settled on the west side of the Milwaukee River. In competition with Juneau, Kilbourn established Kilbourntown there, making sure that the streets running toward the river did not match up with those on the east side. This accounts for the large number of angled bridges that still exist in Milwaukee today. Further, Kilbourn distributed maps of the area that showed only Kilbourntown, implying that Juneautown did not exist or that the east side of the river was uninhabited and thus undesirable.

The third prominent builder, George H. Walker, claimed land to the south of the Milwaukee River, where he built a log house in 1834. This area grew and became known as Walker's Point.

The proximity of the towns sparked tensions in 1845 after the completion of a bridge built between Kilbourntown and Juneautown. Kilbourn and his supporters viewed the bridge as a threat to their community and ultimately led to Kilbourn destroying part of the bridge. Over the next few weeks, skirmishes broke out between the inhabitants of the two towns; while no one was killed, several people were seriously injured. After this event, known as the Milwaukee Bridge War, the two towns made greater attempts at cooperation.

By the 1840s, the three towns had grown to such an extent that on January 31, 1846 they combined to incorporate as the City of Milwaukee and elected Solomon Juneau as the city's first mayor. A great number of German immigrants had helped increase the city's population during the 1840s and continued to migrate to the area during the following decades.

Milwaukee became known as the "Deutsches Athen" (German Athens), and into the 20th century, there were more German speakers and German-language newspapers than there were English speakers and English-language newspapers in the city. To this day, the Milwaukee phone book includes more than 40 pages of Schmitts or Schmidts, far more than the pages of Smiths.

In the mid-19th century Milwaukee earned the nickname "Cream City," which refers to the large number of cream colored bricks that came out of the Menomonee River Valley and were used in construction. At its peak, Milwaukee produced 15 million bricks a year, with a third going out of the state.

1850 to 1899

During the middle and late 19th century, Wisconsin and the Milwaukee area became the final destination of many German immigrants fleeing the Revolutions of 1848. In Wisconsin they found the inexpensive land and the freedoms they sought. The German heritage and influence in the Milwaukee area is widespread.

On November 14, 1856 Solomon Juneau died at the age of 63.

The Milwaukee Bar Association was founded in 1858. It is the fourth oldest of such organizations in the United States and now has over 2,600 members.

On May 5, 1886 the Bay View Massacre occurred, in which striking steelworkers who were marching toward a mill in the Bay View section of Milwaukee were intercepted by a squad of National Guardsmen who, under orders from the Wisconsin Governor, fired point blank into the strikers, killing seven.

In March 1889, Milwaukee had four days of protest and one day of rioting against its Chinese laundrymen. Sparking this citywide disturbance were allegations of sexual misconduct between two Chinese and several underaged white females. The unease and tension in the wake of the riot was assuaged by the direct disciplining of the city's Chinese.[8]

The late 19th century saw the incorporation of Milwaukee's first suburbs. Bay View existed as an independent village from 1879 to 1886. In 1892, Whitefish Bay, South Milwaukee, and Wauwatosa incorporated. They were followed by Cudahy (1895), North Milwaukee (1897) and East Milwaukee, (later known as Shorewood), in 1900. The early 20th century saw the additions of West Allis (1902) and West Milwaukee (1906), which completed the first generation of so-called "inner-ring" suburbs.

In general, suburbs along the north shore of Lake Michigan were residential and wealthier and suburbs along the south shore were industrial and working class. The western suburbs were mixed—North Milwaukee and West Allis being primarily industrial, and Wauwatosa being primarily residential. Wauwatosa was widely recognized as Milwaukee's first "bedroom suburb," though it developed its own set of social, economic, and religious institutions.

In 1895, the Milwaukee City Hall was completed. Containing 15 stories and topping out at 393 feet, the City Hall was the tallest habitable building in the world upon its completion (a title it maintained until the Park Row Building was completed in New York City in 1899)[9] and one of the tallest structures overall, behind such non-habitable buildings as the Eiffel Tower and the Washington Monument. It remained the tallest seat of government until 1901, when Philadelphia City Hall was completed.

1900 to 1959

During the first half of the 20th century, Milwaukee was the hub of the socialist movement in the United States. Milwaukeeans elected three Socialist mayors during this time: Emil Seidel (1910–1912), Daniel Hoan (1916–1940), and Frank Zeidler (1948–1960), and remains the only major city in the country to have done so.

Often referred to as "Sewer Socialists," these Milwaukee Socialists were characterized by their practical approach to government and labor. These practices emphasized cleaning up neighborhoods and factories with new sanitation systems, city owned water and power systems, and improved education systems. During this period, socialist mayor Daniel Hoan implemented the country's first public housing project, known as Garden Homes.[10] The socialists' influence began to dwindle in the late 1950s amidst the "red scare".

On November 24, 1917, Milwaukee was the site of a terrorist explosion when a large black powder bomb [11] exploded at the central police station at Oneida and Broadway.[12] Nine members of the department were killed in the blast, along with a female civilian, Catherine Walker.[11][13] It was suspected at the time that the bomb had been placed outside the church by anarchists, particularly the Galleanist faction led by adherents of Luigi Galleani. At the time, the bombing was the most fatal single event in national law enforcement history,[14] only surpassed later by the World Trade Center terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 when 72 law enforcement officers representing eight different agencies were killed.

Also during this time, a small, but burgeoning community of African-Americans who emigrated from the south formed a community that would come to be known as Bronzeville. This area, which was located on and near what are now known as Old World Third Street and Martin Luther King Drive, soon became known as a "Harlem of the Midwest" for its jazz clubs and juke joints which attracted both local and nationally renowned musicians such as B.B. King and Ella Fitzgerald. Bronzeville's significance began to fall off as the heart of Milwaukee's Black community shifted north following World War II after the building of a major expressway (Interstate 43) which destroyed the geographic continuity of the district. Today, the area has been experiencing something of a revival as it has seen the arrival of several new businesses, restaurants, condos, coffee shops and night clubs that seek to recapture the prominence the area once had.

In 1953, over 7,000 workers at six breweries in Milwaukee went on strike for over 76 days.

Into the late 1950s, Milwaukee, like many northern industrial cities, grew tremendously. Having been home historically to immigrants from European nations, as well as the northward migration of African-Americans from the Southern United States and industrial workers from Wisconsin's hinterlands and other parts of the United States, the city had acquired a dense population in the first half of the 20th century.

As Milwaukee's suburbs proliferated and the population of the city center began to disperse, Milwaukee annexed and incorporated the surrounding lands, recapturing a portion of its departing tax base and simultaneously supplying these areas with much-needed city services. The first plan for Wisconsin's highway system, with an aim to improve Milwaukee's worsening automotive congestion, was submitted in 1945, although construction did not begin until the late 1950s.

1960 to 1995

Milwaukee's population peaked in 1960, according to the decennial US Census, with a count of 741,324 and a national ranking as the 11th largest American city. Milwaukee made its final boundary annexations and consolidations in the same year, when it established the configuration of borders seen today.

In 1967 a riot rocked the city. The 1967 Milwaukee riot was one of 159 race riots that swept cities in the United States during the long, hot summer of 1967. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, African American residents, outraged by the slow pace in ending housing discrimination and police brutality, began to riot on the evening of July 30, 1967. A fight between teenagers escalated into full-fledged rioting with the arrival of police. Within minutes, arson, looting, and sniping were ravaging the North Side of the city, primarily the 3rd Street Corridor. (Excerpt from “1967 Milwaukee riot” Wikipedia, see full entry for more)

By 1970, as the city continued to exhibit the trends of decentralization, its population had fallen to 717,099 as the 12th largest American city. In 2000, it was the 19th largest, with a population of 596,974. The population decline was a result of various factors. Starting in the late 1960s, as in many cities in the Great Lakes "rust belt," Milwaukee saw the loss of blue collar jobs and the phenomenon of "white flight."

The construction of Milwaukee's interstate highway system, beginning in 1964 with the completion of its first seven miles of I-94, heralded an age of greater decentralization, as southeastern Wisconsin suburbs continued to proliferate along interstate corridors, providing an alternative to crowded city living. Nevertheless, a backlash against the freeway in the late 1960s and early 1970s virtually ground Milwaukee's freeway construction to a halt, leaving the city with about 50% of the highways recommended by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission's freeway plan.

1996 to 2020

In recent years the city began to make strides in improving its economy, neighborhoods, and image, resulting in the revitalization of neighborhoods such as the Historic Third Ward, the East Side, and more recently, Bay View, along with attracting businesses to its downtown area. Marquette University has dedicated major projects to the Marquette Hill neighborhood including "campus town" and additional academic buildings, while demolishing some historic buildings and taking over other structures for its own use.

The city continues to plan for revitalization through various projects. Largely because of its efforts to preserve its history, in 2006 Milwaukee was named one of the "Dozen Distinctive Destinations" by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[15]

In the early 21st century, the city has undergone a large number of construction projects at rates not seen since the 1960s.[16]

In 2020, Milwaukee recorded 189 homicides,[17] exceeding the all-time homicide record of 174 which was set in 1993.[18]

See also

- List of mayors of Milwaukee

- The Making of Milwaukee, a film about the history of Milwaukee

- Sewer Socialism

- History of Wisconsin

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- List of Milwaukeeans

- Neighborhoods of Milwaukee

- Germans in Milwaukee

- Jews in Milwaukee

References

- ↑ White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9781139495684.

- ↑ Bruce, William George (1936). A Short History of Milwaukee. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Bruce Publishing Company. p. 15. LCCN 36010193.

- ↑ "Ojibwe Dictionary". Freelang. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Buck, James S (1890). Pioneer History of Milwaukee. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Swain.

- ↑ Fowler, William (2005). Empires at War. New York: Walker & Company. p. 68. ISBN 9780802719355.

- ↑ White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 400. ISBN 9781139495684.

- ↑ Jaqueline Peterson, "Many Roads to Red River: Metis genesis in the Great Lakes region, 1680-1815" in The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Metis in North America, Jaqueline Peterson and Jennifer S. H. Brown, ed. (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1985 reprinted St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2001), p. 44

- ↑ Jew, Victor. "'Chinese Demons': The Violent Articulation of Chinese Otherness and Interracial Sexuality in the U.S. Midwest, 1885-1889." Journal of Social History v. 37 no. 2 (2003), pp. 389-410. doi:10.1353/jsh.2003.0181

- ↑ "Milwaukee City Hall". Skyscraper Source Media. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "GARDEN HOMES HISTORIC DISTRICT HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT APRIL 2011" (PDF). City.milwaukee.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- 1 2 Balousek, Marv, and Kirsch, J. Allen, 50 Wisconsin Crimes of the Century, Badger Books Inc. (1997), ISBN 1-878569-47-3, ISBN 978-1-878569-47-9, p. 113

- ↑ The Indianapolis Star, "Bomb Mystery Baffles Police", November 26, 1917

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Milwaukee Police Department Officer Memorial Page" - ↑ Deadliest Days in Law Enforcement History, National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund (November 24, 1917) http://www.nleomf.org/facts/enforcement/deadliest.html Archived 2016-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Dozen Distinctive Destinations - Milwaukee". National Trust for Historic Preservation. 2006.

- ↑ "Extraordinary building boom is reshaping Milwaukee's skyline". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- ↑ "Milwaukee's historic year of violence concludes with 189 people killed in homicides". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. January 1, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Milwaukee Co. homicide numbers exceed all-time record of 174 set in 1993". FOX6 News. October 26, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

Further reading

- Booth, Douglas E. "Municipal Socialism and City Government Reform: The Milwaukee Experience, 1910-1940". Journal of Urban History 12, no. 1 (November 1985): 51-74.

- Carriere, Michael, and David Schalliol. "There Grows the City: A Long History of Urban Agriculture in Milwaukee, Wisconsin." Journal of Urban History (2022): 00961442221100490.

- Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City. (Harvard University Press, 1976).

- Hurley, Alec S., and Annette R. Hofmann. "Between Pints and Performances: The Work of George Brosius in the Nineteenth-Century Turner Stronghold of Milwaukee." Journal of Sport History 48.2 (2021): 186-200.

- Eimer, Stuart. "From 'business unionism' to 'social movement unionism': The case of the AFL-CIO Milwaukee County Labor Council." Labor Studies Journal 24.2 (1999): 63-81. online

- Gavett, Thomas William. Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

- Greene, Victor. "Dealing with diversity: Milwaukee's multiethnic festivals and urban identity, 1840-1940." Journal of Urban History 31.6 (2005): 820-849.

- Gurda, John. Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee's Past. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2007.

- Hintz, Martin. A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze (Arcadia Publishing, 2011).

- Hintz, Martin. Irish Milwaukee (Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

- Holli, Melvin G., and Jones, Peter d'A., eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980 (Greenwood Press, 1981) short scholarly biographies each of the city's mayors 1820 to 1980. online; see index at p. 409 for list.

- Holter, Darryl. "Sources of CIO success: The New Deal years in Milwaukee." Labor History 29.2 (1988): 199-224.

- Jarosinski, Eric. "“Der unrealistische Genosse”: Heinrich Bartel and Milwaukee Socialism." Yearbook of German-American Studies 37 (2002): 125-134.online

- Kates, James. "Editor, publisher, citizen, socialist: Victor L. Berger and his Milwaukee Leader." Journalism History 44.2 (2018): 79-88. online

- Kenny, Judith T., and Jeffrey Zimmerman. "Constructing the ‘Genuine American City’: neo-traditionalism, New Urbanism and neo-liberalism in the remaking of downtown Milwaukee." Cultural Geographies 11.1 (2004): 74-98.

- Leahy, Stephen M. The Life of Milwaukee's Most Popular Politician, Clement J. Zablocki: Milwaukee Politics and Congressional Foreign Policy (Edwin Mellen Press, 2002).

- Leavitt, Judith W. The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform. (University of Wisconsin Press, 1996).

- Mukherji, S. Ani. "Reds Among the Sewer Socialists and McCarthyites: The Communist Party in Milwaukee." American Communist History 16.3-4 (2017): 112-142.

- Pienkos, Donald. "Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930". Wisconsin Magazine of History 61, no. 3 (Spring 1978): 179-209.

- Rast, Joel. "Annexation policy in Milwaukee: An historical institutionalist approach." Polity 39 (2007): 55-78.

- Simon, Roger D. "The City-Building Process: Housing and Services in New Milwaukee Neighborhoods 1880-1910". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 86, pt. 6 (1996): 1-163.

- Still, Bayrd. "Milwaukee, 1870-1900: The Emergence of a Metropolis". Wisconsin Magazine of History 23 no. 2 (December 1939): 138-162.

- Still, Bayrd. Milwaukee: the History of a City. (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948); a standard scholarly history.

- Wachman, Marvin. History of the Social-Democratic Party of Milwaukee, 1897-1910. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1945).

- Zeitlin, Richard H. Germans in Wisconsin (Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013).

Education and race

- Connell, Tula. "1950S Milwaukee: race, class, and a City divided." Labor Studies Journal 42.1 (2017): 27-51.

- Dougherty, Jack. More than one struggle: The evolution of Black school reform in Milwaukee (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004).

- Jones, Patrick D. The Selma of the North: Civil rights insurgency in Milwaukee (Harvard University Press, 2009)

- Jones, Sandra E. Voices of Milwaukee Bronzeville (Arcadia Publishing, 2021).

- Miner, Barbara J. Lessons from the Heartland : A Turbulent Half-Century of Public Education in an Iconic American City (New Press, 2013) on Milwaukee schools

- Nelsen, James K. Educating Milwaukee: How one city’s history of segregation and struggle shaped its schools (Wisconsin Historical Society, 2015).

- Rury, John L. and Frank A. Cassell, eds. Seeds of Crisis: Public Schooling in Milwaukee since 1920 (1993)

- Trotter, Joe William. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985.

Pre 1939 titles

- Bruce, William George. Milwaukee's Century of Progress. Milwaukee: Wright Directory Co., 1918.

- Bruce, William George. History of Milwaukee, City and County. Chicago—Milwaukee: S. J. Clarke, 1922. Vol. 1. Vol. 2. Vol. 3.

- Buck, James S. Pioneer History of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Symes, Swain & Co.

- Conrad, Howard Louis (ed.) History of Milwaukee from Its First Settlement to the Year 1895]. Chicago: American Biographical Publishing Co., 1895. Vol. 1

- Gregory, John Goadby. History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Chicago-Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke, 1931. (4 vols.). detailed popular history with many biographies

- Harger, Charles B. Milwaukee Illustrated., Milwaukee: W. W. Coleman, 1877.

- King, Rufus, "A Sketch of Milwaukee". in Erving, Burdick & Co.'s Milwaukee City Directory, for 1857 & 1858. Milwaukee: King, Jermain & Co., 1857.

- Koss, Rudolph A. Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Schnellpressendruck des "Herold", 1871. (in German)

- Larson, Laurence Marcellus. "A Financial and Administrative History of Milwaukee", Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin, 242 (June 1908).

- Milwaukee: Seventy-five Years a City. Milwaukee: 75th Anniversary Committee, 1921.

- Newcomb, T. Night in Milwaukee. New York: T. Newcomb, 1917.

- Watrous, Jerome A. Memoirs of Milwaukee County. Madison: Western Historical Association, 1909. Vol. 1. Vol. 2.

- Watrous, R. B. (comp.) Milwaukee: a Bright Spot. Milwaukee: Citizens' Business League, 1902.

- Wolf, John R. Wolf's Book of Milwaukee Dates: A Condensed History of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Evening Wisconsin Co., 1915.

External links

- The Making of Milwaukee- television mini-series

- Archives on Milwaukee history from UWM

- Milwaukee Neighborhoods: Photos and Maps 1885-1992 - Digital collection from the UWM