Henry | |

|---|---|

Henry walking on his murderer Lalli. Painting from the Church of Taivassalo about 1450. | |

| Bishop, missionary, martyr | |

| Born | 1100 Kingdom of England |

| Died | Traditionally January 20, 1156[1] Lake Köyliö, Finnic tribal lands (now Finland) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation[2] |

| Major shrine | Earlier Cathedral of Turku, today only Catholic Cathedral of Helsinki |

| Feast | January 19 |

| Patronage | Catholic Cathedral of Helsinki |

| Controversy | Existence disputed |

Henry (Finnish: Henrik; Swedish: Henrik; Latin: Henricus; died c. 20 January 1156[1]) was a medieval English clergyman. He came to Sweden with Cardinal Nicholas Breakspeare in 1153 and was most likely designated to be the new Archbishop of Uppsala, but the independent church province of Sweden could only be established in 1164 after the civil war, and Henry would have been sent to organize the Church in Finland, where Christians had already existed for two centuries.

According to legend, he entered Finland together with the king, Saint Eric of Sweden and died as a martyr, becoming a central figure in the local Catholic Church. However, the authenticity of the accounts of his life and ministry are widely disputed and there are no historical records of his birth, existence or death.

Together with his alleged murderer, peasant Lalli, Henry is an important figure in the early history of Finland. His feast is celebrated by the majority Lutheran Church of Finland,[3] as well as by the Catholic Church of Finland. He is commemorated in the liturgical calendars of several Lutheran and Anglican churches.

Legend

Vita and miracula

The legend of Bishop Henry's life, or his Vita, was written 150 years after his time, at the end of the 13th century, and contains little concrete information about him. He is said to have been an English-born bishop in Uppsala at the time of King Eric the Saint of Sweden in the mid-12th century, ruling the peaceful kingdom with the king in heavenly co-existence. To tackle the perceived threat from the non-Christian Finns, Eric and Henry were forced to do battle with them. After they had conquered Finland, baptized the people and built many churches, the victorious king returned to Sweden while Henry (Henricus) remained with the Finns, more willing to live the life of a preacher than that of a high bishop.[4]

The legend draws to a conclusion as Henry attempted to give a canonical punishment to a murderer. The accused man became enraged and killed the bishop, who was thus considered to be a martyr.[4]

The legend strongly emphasizes that Henry was a Bishop of Uppsala, not a Bishop of Finland[5] which became a conventional claim later on, also by the church itself.[6] He stayed in Finland out of pity, but was never appointed as a bishop there. The legend does not state whether there had been bishops in Finland before his time or what happened after his death; it does not even mention his burial in Finland. The vita is so void of any concrete information about Finland that it could have been created anywhere.[4] The Latin is scholastic and the grammar is in general exceptionally good.[7]

Henry's Vita is followed by the more local miracula, a list of eleven miracles that various people were said to have experienced sometime after the bishop's death. With the exception of a priest in Skara who suffered a stomach ache after mocking Henry, all miracles seem to have taken place in Finland. The other miracles, which usually occurred following prayer to Bishop Henry, were:[4]

- The murderer lost his scalp when he put the bishop's hat on his head

- The Bishop's finger was found the next Spring

- A boy was raised from the dead in Kaisala

- A girl was raised from the dead in Vehmaa

- A sick woman was healed in Sastamala

- A Franciscan called Erlend had his headache healed

- A blind woman got back her eyesight in Kyrö

- A man with a paralyzed leg could walk again in Kyrö

- A sick girl was healed

- A group of fishermen from Kokemäki survived a storm

Most versions of Henry's legend only include a selection of these miracles.[8]

Development of the legend

Henry and his crusade to Finland were also a part of the legend of King Eric. The appendix of the early 13th century Västgötalagen, which has a short description of Eric's memorable deeds, also makes no reference to Henry or the crusade.[9] Henry and the crusade do not appear until a version of Eric's legend that dates to 1344. Similarities in the factual content and phraseology regarding the common events indicate that either one of the legends has acted as the model for the other.[10] Henry's legend is commonly considered to have been written during the 1280s or 1290s at the latest, for the consecration of the Cathedral of Turku in 1300, when his alleged remains were translated there from Nousiainen, a parish not far from Turku.[11]

Absence from the historical record

Yet, even as late as in the 1470s, the crusade legend was ignored in the Chronica regni Gothorum, a chronicle of the history of Sweden, written by Ericus Olai, the Canon of the Uppsala cathedral.[12]

Noteworthy in the development of the legend is that the first canonically elected Bishop of Turku, Johan (1286–1289) of Polish origin, was elected as the Archbishop of Uppsala in 1289, after three years in office in Turku. The Swedish bishops of Finland[13] before him, Bero, Ragvald and Kettil, had apparently been selected by the King of Sweden. Related to the new situation was also the appointment of the king's brother as the Duke of Finland in 1284, which challenged the Bishop's earlier position as the sole authority on all local matters. Johan was followed in Turku by Bishop Magnus (1291–1308), who had been born in Finland.[14]

In 1291 a document by the cathedral chapter makes no reference to Henry even though it mentions the cathedral and election of the new bishop many times.[15] A papal letter by Pope Nicholas IV from 1292 has the Virgin Mary as the sole patrona in Turku.[16]

Appearance in the historical record

The first mention of Bishop Henry in historical sources is from 1298, when he is mentioned along with king Eric in a document from a provincial synod of Uppsala in Telge. This document, although mentioned many times as a source over the centuries, was not correctly dated until 1910.[17]

The legend itself is also first referred in a letter by the Archbishop of Uppsala in 1298, where Eric and Henry are mentioned together as martyrs who needed to be prayed to for the sake of the situation in Karelia,[18] associating their alleged crusade to Finland with the new expeditions against Novgorod. The war between Novgorod and Sweden for the control of Karelia had started in 1293. The first certain appearance of Henry's image in the seal of the Bishop of Turku is not until 1299.[19]

The first mention of Henry of Uppsala being the patron saint of Turku cathedral is not until 14 August 1320, when he is mentioned as the second patron of the cathedral after Virgin Mary.[20] When he is later addressed by Pope Boniface IX as the patronus of the Cathedral of Turku along with the Virgin Mary, and referred to as a saint, it was in the year 1391.[21] Some sources claim that Henry was canonized in 1158, but this information has been traced to a late publication by Johannes Vastovius in 1623 and is generally regarded as a fabrication.[22]

Thus, Henry's veneration as a saint and his relation to King Eric seem to have emerged in the historical record at the same time in the mid-1290s with strong support from the church. This correlates with the start of the war against Novgorod. Sources do not support the popular assumption that Henry's cult developed in Nousiainen and gradually spread among ordinary people before official adoption. In 1232, the church in Nousiainen was consecrated only to the Virgin Mary,[23] and it was not until 1452 that Henry was mentioned as the patronus of Nousiainen.[24]

Veneration

Despite the high-profile start of Henry's cultus, it took more than 100 years for the veneration of Saint Henry to gain widespread acceptance throughout Sweden. As of 1344 there were no relics of the bishop in the Cathedral of Uppsala. According to one biographer, Henry's veneration was rare outside the Diocese of Turku throughout the 14th century.[25] Vadstena Abbey near Linköping seems to have played a key role in establishment of Henry's legend elsewhere in Sweden in the early 15th century.[26] Henry never received the highest totum duplex veneration in Uppsala nor was he made a patronus of the church there, which status he had both in Turku and Nousiainen.[27]

At the end of the Roman Catholic era in Sweden, Henry was well established as a local saint. The dioceses in Sweden and elsewhere venerating Henry were as follows, categorized by his local ranking:[28]

- Totum duplex: Turku, Linköping, Strängnäs

- Duplex: Uppsala, Lund (Denmark), Västerås, Växjö

- Semiduplex: Nidaros (Norway)

- Simplex: Skara[29]

Henry seems to have been known in northern Germany, but he was largely ignored elsewhere in the Roman Catholic world.[30]

In the Bishopric of Turku, the annual feast day of Henry was January 20 (talviheikki, "Winter Henry"), according to traditions the day of his death. Elsewhere his memorial was held already on January 19,[31] since more prominent saints were already commemorated on January 20. After the Reformation, Henry's day was moved to the 19th in Finland as well.[32] The existence of the feast day is first mentioned in 1335, and is known to have been marked in the liturgical calendar from the early 15th century onwards. Another memorial was held on June 18 (kesäheikki, "Summer Henry") which was the day of the translation of his relics to the Cathedral of Turku.[33]

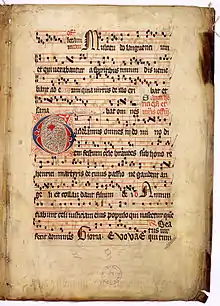

Gaudeamus omnes ("Let all rejoice"), a Gregorian introit for the Mass in honor of Henry has survived within the late 14th or early 15th century Graduale Aboense.[34]

Political dimensions

| Christianization of Finland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| People | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||

| Kokemäki ● Köyliö ● Nousiainen ● Koroinen ● Turku Cathedral | ||||||||

| Events | ||||||||

| Finnish-Novgorodian wars First Swedish Crusade Second Swedish Crusade Third Swedish Crusade | ||||||||

According to legend, establishment of the church of Finland was entirely the work of the saint-king Eric of Sweden, assisted by the bishop from the most important diocese in the country. The first half of the legend describes how the king and the bishop ruled Sweden like 'two great lights' with feelings of 'internal love' toward each other, emphasizing the peaceful coexistence of the secular and ecclesiastical rule during a happy era when 'predatory wolves' could not hit their 'poisonous teeth against the innocent'.[4] The reality was quite different – Eric's predecessor, Eric himself and two of his successors were all murdered almost within a decade, one of the bloodiest times for the Swedish royalty. In the 1150s, the Bishop of Uppsala was also in a bitter fight with the Bishop of Linköping over which see would become archiepiscopal.[35] The crusade itself is described as a brief and bloodless event that was only performed to bring the "blind and evil heathen people of Finland" under Christian order.[4]

The writer of the legend seems to have been especially interested in presenting the bishop as a humble martyr. He has fully ignored his place of death and burial and other "domestic" Finnish interests, which were much more apparent in folk traditions. The legend and folk traditions eventually influenced each other, and the church gradually adopted many additional details to its saint bishop.[36]

Folk traditions

Among the many folk traditions about Henry, the most prominent is the folk poem "The Death-lay of Bishop Henry" (Piispa Henrikin surmavirsi). The poem almost completely ignores Henry's life and ministry and concentrates on his death.[37]

Henry's origins

According to the poem, Henry had grown up in "Cabbage Land" (Kaalimaa), which has puzzled Finnish historians for centuries. The name might be connected to a coastal area in northern Finland Proper called Kaland, which is also mentioned in conjunction with an unrelated early preacher in Vesilahti, upper Satakunta, whose local name was "Fish of Kaland" (Kalannin kala, also known as Hunnun herra).[38] Bishop Mikael Agricola wrote in his Se Wsi Testamenti in 1548, that the earliest Swedish settlers in Finland had come from Gotland to the islets on the coast of Kaland, being harassed by Finns and seeking help from their relatives in Sweden.[39]

It has also been suggested that the name might be related to Gaelic, which would presumably have referred to the bishop's Scottish origins, though the legend gives him as a native Englishman.[40]

Folk traditions have no information on the crusade whatsoever. King Eric is briefly mentioned in the death-lay's preface as Henry's concerned "brother". Henry appears as a lone preacher who moved around southwestern Finland more or less on his own. Besides the name, he has only little in common with the Henry in the church vita.[41]

Kokemäki is often mentioned in traditions as a place where Henry preached. Kokemäki was later one of the central parishes in Satakunta. This province was first mentioned in historical documents in 1331.[42]

Death and burial

The death-lay's version of the bishop's death was different from the vita. The bishop's killer was called Lalli. Lalli's wife Kerttu falsely claimed to him that upon leaving the manor, their ungrateful guest Henry, travelling around on his own in the middle of winter, had without permission or recompense, through violence, taken food, cake from the oven and beer from the cellar, for himself and hay for his horse, and left nothing but ashes. This is supposed to have enraged Lalli so that he immediately grabbed his skis and went in pursuit of the thief, finally chasing Henry down on the ice of Lake Köyliönjärvi in Eura. There he killed him on the spot with an axe.[37] Lalli then proceeded to steal the late holy man's hat, called a mitre, and place it on his own head. When Lalli's mother questioned him about where he found the hat, he attempted to take it off, but with it came his scalp. Lalli then died a painful death. The 17th century lay version smugly comments that:[43]

Now the bishop is in joy,

Lalli in evil torture.

The bishop sings with the angels,

Performs a joyful hymn.

Lalli is skiing down in hell.

His left ski slides along.

Into the thick smoke of torture.

With his staff he strikes about:

Demons beset him cruelly.

In the swelter of hell

They assail his pitiful soul.

The 17th century lay version of the tale was intended to be performed during the annual pilgrimage along Henrik's final route.

In some versions of the poem, considered older, Lalli's weapon was a sword. The axe was the murder weapon of Saint Olaf, who was very popular in Finland and may have influenced Henry's legend.[43] However, since Lalli is not portrayed as a member of the upper class, it is unlikely that he possessed an expensive weapon like a sword, and the axe is a more historically likely choice for Henry's murder.

Before his death, Henry instructed the coachman to gather his remaining body parts in a cloth tied with blue string, place it in a cart drawn by a stallion. When the stallion broke, he was to replace it with an ox, and when the ox stopped, he was to build a church.[37] This is where Henrik's remains were to be buried.

Medieval folk traditions enumerate the pestilences and misfortunes which befell Lalli after his slaying of the bishop. His hair and scalp are said to have fallen out as he took off the bishop's cap, taken as a trophy. Removing the bishop's ring from his finger, just bones remained. Eventually he ran into a lake and drowned himself.[37][44]

Development of folk traditions

Basically the death-lay is a simple story of a short-tempered man who falls victim of his "bad-mouthed wife's" sharp tongue. The poem has no pity for Lalli, and he is not depicted as a hero in a story whose true antagonist is Kerttu. The depiction of Henry's death built on an independent tradition that was once in direct competition with that of the legend, which is largely forgotten today. It remains unknown whether the two traditions were built around the same person.[41]

The poem, following the traditional Kalevala metre, has survived as several 17th and 18th century literations from various parts of Finland. Some of its elements appear in earlier works, but it hardly dates older than the vita.[45] There is debate on whether the original poem was constructed by one or more individuals. The writer has however had superficial understanding of the church legends.[45]

Both Lalli (Laurentius) and Kerttu (Gertrud) are originally German names, which might indicate that the poem was partly constructed on foreign models, whose influence is visible in other aspects, too. The way Lalli is manipulated to commit the crime and what happens to him later seem to be taken from a medieval Judas fable.[44] Extensive borrowing from unrelated Finnish legends from the pre-Christian era has taken place as well, leaving quite little original material left at all.[46]

Based on finds from medieval church ruins in the tiny island of Kirkkokari ("Church Rock", previously known as the "Island of Saint Henry") in Lake Köyliönjärvi, the bishop's veneration began in the latter half of the 14th century, well after Henry had received his official status as a local saint, and 200 years after his alleged death.[47] A small granary in the nearby Kokemäki, claimed to have been the bishop's place of rest the night before his death, could not be dated earlier than the late 15th century in dendrochronological examinations.[48]

However, the poem's claim that Henry was buried in Nousiainen was already held to be true around 1300, when his alleged bones were translated from Nousiainen to the Cathedral of Turku. A mid-15th century Chronicon episcoporum Finlandensium also confirmed Köyliö as the place of his death.[49] Neither place is mentioned in the vita in any way. The church seems to have gradually complemented its own legends by adopting elements from the folk traditions, especially during the 15th century.[45]

Historical sources

Today, the legend of Henry is challenged by some historians to the point of being labelled as pure imagination. Completely invented saints were not exceptional in Europe,[50] and there is no direct evidence of either the crusade or Henry.[51]

The bishop's alleged violent death however, is no reason to doubt his potential existence, as many bishops were murdered during the turmoils of the 12th and 13th centuries, although most were not elevated to sainthood. Saxo Grammaticus said of the Battle of Fotevik in 1134 that never had so many bishops been killed at the same time. Notable bishops that died violently included the Archbishop of Uppsala in 1187,[52] Bishop of Estonia in 1219[53] and Bishop of Linköping in 1220.[54]

Bishop of Uppsala

There is no historical record of a Bishop of Uppsala called Henry during the reign of King Eric (about 1156–1160). Early phases of the diocese remain obscure up to the point of Stefan, who was appointed as the archbishop in 1164.[55]

A certain Henry is mentioned in Incerti scriptoris Sueci chronicon primorum in ecclesia Upsalensi archiepiscoporum, a chronicle of Uppsala archbishops, before Coppmannus and Stefan, but after Sverinius (probably mentioned in German sources in 1141/2 as "Siwardus"[56]), Nicolaus and Sweno.[57] Besides the name, the chronicle knows that he was martyred and buried in Finland in the Cathedral of Turku. Latest research dates the chronicle to the early 15th century when Henry's legend was already established in the kingdom, leaving only little significance to its testimony.[58]

A late 15th century legenda nova claimed that Henry had come to Sweden in the retinue of papal legate Nicholas Breakspear, the later Pope Adrian IV, and appointed as the Bishop of Uppsala by him. Even though legenda nova states 1150 as the year of the crusade, it is certain from other sources that Nicholas really was in Sweden in 1153. It is not known whether this was just an inference by the writer, based on the fact that also Nicholas was an Englishman.[59] However, there is no information about anyone called as Henry accompanying the legate in any source describing the visit, nor him appointing a new bishop in Uppsala.[60] Another claim by legenda nova was that Henry was translated to Turku cathedral already in 1154, which certainly was false since the cathedral was built only in the 1290s.[61] In the late 16th century, Bishop Paulus Juusten claimed that Henry had been the Bishop of Uppsala for two years before the crusade. Based on these postulates, early 20th-century historians assembled 1155 as the year of the crusade and 1156 as the year of Henry's death.[61] Historians from different centuries have also suggested various other years from 1150 to 1158.[1]

Contradicting these claims, the medieval Annales Suecici Medii Aevi[62] and the 13th century legend of Saint Botvid[63] mention some Henry as the Bishop of Uppsala (Henricus scilicet Upsalensis) in 1129, participating in the consecration of the saint's newly built church.[64] He is apparently the same Bishop Henry who died at the Battle of Fotevik in 1134, fighting along with the Danes after being banished from Sweden. Known from the Chronicon Roskildense written soon after his death and from Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum from the early 13th century, he had fled to Denmark from Sigtuna, the see of the early Uppland bishops before it was moved a few kilometers to its later location in Uppsala sometime before 1164.[65][66] He is ignored in all Swedish bishop chronicles, unless he is the same Henry who was later redated to the 1150s. That would make the claim about him coming to Finland with King Eric a late innovation, where memory about a killed bishop in Uppsala sometime in the 12th century was reused in a new context.[67]

Noteworthy also, is a story written down by Adam of Bremen in his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (Deeds of Bishops of the Hamburg Church) from 1075/6 about a certain foreigner called Hericus, who was slain and martyred while preaching among the Sueones. Adam had heard the story from King Sweyn II of Denmark.[68] According to some historians, resemblance to later legend about an English-born Henricus, who was allegedly slain and martyred in Finland, is too striking to be a coincidence.[69]

Bishop of Finland

No historical source remains that would confirm the existence of a bishop named Henry in Finland. However, papal letters mentioning an unidentified Bishop of Finland in 1209, 1221, 1229 and 1232 have survived.[70] Some copies of another papal letter from 1232 call the bishop as "N.",[23] but the letter "N" may originally have also been something resembling it. The first certainly known Bishop of Finland is Thomas, who is first mentioned in 1234.[71] It is however possible, that Fulco, the Bishop of Estonia mentioned in sources from 1165 and 1171,[72] was the same as Folquinus, a legendary Bishop of Finland at the end of the 12th century, but this remains only a theory.[73]

No Bishop or Diocese of Finland is mentioned in a papal letter from 1171 (or 1172) by the seemingly well-informed Pope Alexander III, who otherwise addressed the situation of the church in Finland. The Pope mentions that there were preachers, presumably from Sweden, working in Finland and was worried about their bad treatment by the Finns.[74] The Pope had earlier in 1165 authorized the first missionary Bishop of Estonia to be appointed, and was a close acquaintance of both Eskil, the Archbishop of Lund, and Stefan, the Archbishop of Uppsala, who both had spent time with him in France where he had been exiled in the 1160s. Following the situation in Estonia, the Pope personally interfered in the Estonian mission in 1171, ordering assistance for the local Bishop Fulco from Norway.[72]

No surviving list of bishops or dioceses under the Archbishop of Uppsala from 1164, 1189, 1192, 1233, 1241 or 1248 contains any reference to Finland, neither factual or propagandist. No claim about a Swedish bishop in Finland is made in any other source from the era prior to the so-called Second Swedish Crusade in 1249.[75]

The first mention of a bishop in Finland is from a papal letter in 1209. It was sent to Archbishop Anders of Lund by Pope Innocent III as a reply to the Archbishop's earlier letter which has not survived. According to the Archbishop, the Bishop of the newly established church in Finland was dead, apparently from natural causes since his passing away is mentioned to have been "lawful", and the see had been vacant for some time. The Archbishop had complained to the Pope how difficult it was to get anyone to be a bishop in Finland and planned to appoint someone without formal adequacy, who was already working in Finland. The Pope approved of Archbishop's suggestion without questioning his opinions.[76] It is noteworthy that the Archbishop of Uppsala, Valerius (1207–1219/1224), was also in Denmark at the time, temporarily exiled from Sweden after having allied with the deposed King Sverker, yet another exile in Denmark.[55]

Whether the appointment of the said preacher ever took place, remains unknown. Note should be taken that the King of Sweden at the time was Eric, a grandson of his better known namesake Eric the Saint. Eric had taken over Sweden in 1208 and was crowned king two years later. The Pope who had strongly sided with Sverker, ignored him at first, but finally recognized him in 1216, commenting many requests that he had apparently made ever since having taken the office. Based on the papal letter that year, Eric seems to have had a plan to invade some country that allegedly had been "taken from the heathens by his predecessors" and was allowed to install a bishop there.[77] Similar letters were sent to the King of Denmark in 1208 and 1218, who is known to have meant Estonia both times.[75] Sweden also attacked Estonia in 1220.[54] Eric died of illness 1216. Almost nothing is known about his time as the king.[18]

Nevertheless, someone was eventually appointed and installed as the new bishop, since Pope Honorius III sent a letter directly to an unnamed Bishop of Finland in 1221. According to the letter, Archbishop Valerius[78] had followed the situation in Finland and sent a report to the Pope, worried about a threat from unidentified "barbarians". It is notable that when the Pope quoted Valerius in his letter, he calls the church in Finland to have been established "newly", the same claim that Anders had made 12 years earlier.[79] The list of Swedish bishops which survives from this era is from king John Sverkerson's coronation from the year 1219 and it mentions the bishops which have been present at the coronation. Finland as well as Wäxjö are not among those five, which so seem to have been all the bishops of the Swedish realm at that time.[80] So the Finnish bishop's possible position under Uppsala's primacy is highly improbable.[75]

Despite so many high-ranking church representatives being involved in the 1209/1221 arrangements, later chronicles are fully ignorant on the situation in Finland at the time, or if there was even a bishop then. The first 13th-century bishop is said to have been Thomas, and his predecessor remains unknown. According to 15th and 16th century chronicles, Henry was followed by bishops Rodulff and Folquinus, after whom there was a 25–30-year gap before Thomas.[6][49] However, according to the papal letter Ex tuarum no such gap has ever existed, since the archbishop of Lund was given the right to anoint a new bishop to Finland in 1209 after the death of the previous. So the logic and datings of the sixteenth-century writers must be esteemed as false. The date 1209 is far too early for a Dominican like Thomas to step into the office, and so Rodolphus, the first real bishop of Finland and his successor Folquinus must be considered as 13th-century bishops nominated and appointed by the Danish and not by the Swedes.[81] As an extra proof of this the ancient Finnish taxation system of church taxes has its roots in Denmark, not in Sweden.[82] And the same goes to lay taxes especially in the Åland Islands and to the old Finnish monetary system.[83] As J. W. Ruuth already nearly a hundred years ago pointed out, Finland was at that time a Danish and not a Swedish mission territory, where the Danes according to the Danish annals made there expeditions in 1191, 1202 and possible even 1210[84]

Legacy

Relics

Henry was allegedly buried in Nousiainen, from where his bones—or at least something that was thought to be his bones—were transported to Turku in 1300.[85] In addition to traditions, the only source connecting Nousiainen to early bishops is a letter signed by Bishop Thomas in Nousiainen in 1234.[86] Archaeological excavations of pre-Catholic cemeteries in Nousiainen and surrounding parishes show a clear discontinuation of traditions in the early 13th century, but no abrupt changes are apparent in the religious environment among the 12th century finds.[87]

Whatever the case, the bishop's grave seems to have been traced to Nousiainen latest after his elevation to sainthood. A number of medieval documents mention that the bishop's grave continued to be located in the local church, presumably meaning that all the bones had not been translated to Turku.[88] The church was later adorned with a grandiose 15th century cenotaph, whose replica can be found in the National Museum of Finland in Helsinki.[89]

Most of the bones in Turku were still in place in 1720 when they were catalogued for a transfer to Saint Petersburg during the Russian occupation of Finland in the Great Northern War. The man behind the idea was Swedish Count Gustaf Otto Douglas who had defected to the Russian side during the war and was in charge of the grim occupation of Finland.[90] What happened to the bones after that, remains unknown. According to some sources, the Russian vessel transporting the relics sank on the way.[88] However, it is generally acknowledged that a piece of Henry's ulna had been placed in Bishop Hemming's reliquarium that was built in 1514 and treasured in the cathedral. Also enclosed was a piece of parchment stating the bone belonged to Henry. During the restoration work of the cathedral, the relic was relocated to the National Board of Antiquities.[91] It was later placed inside the altar of St. Henry's Cathedral in Helsinki.[92]

In 1924, a jawless skull and several other bones were found in a sealed closet in the Cathedral of Turku. These are also referred to as Henry's relics in popular media and even by the church, even though that designation remains speculative and the bones may have belonged to another saint. The bones are currently stored in the Cathedral of Turku.[91]

Henry's status today

Although Henry has never been officially canonized, he has been referred to as a saint since as early as 1296 according to a papal document of the time,[21] and continues to be called as such today as well.[93][94] On the basis of the traditional accounts of Henry's death, his recognition as saint took place prior to the founding of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints and the official canonization process of the Roman Catholic Church. Henry is currently commemorated on January 19 on the calendar of commemorations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada.[95] January 19 is also Henry's name day (so-called "Heikinpäivä") in Sweden and Finland.[96] He continues to be remembered as a local observance in the Catholic Church of Finland, whose sole cathedral is dedicated to him.[97] The cathedral was consecrated in 1860 and is headed by fr. Marco Pasinato.[98]

The Kirkkokari island in Lake Köyliönjärvi remains the only Catholic place of pilgrimage in Finland, with a memorial service held every year on second Sunday in June before the Midsummer festival. Also the medieval 140 km countryside route, the Saint Henry's Way, from Köyliö to Nousiainen has been marked all the way for people willing to walk through it.[99] Association of "Ecumenical pilgrimage of St. Henry" has been organized around the event.[100]

Based on folk traditions about the bishop's activities, the municipalities of Nousiainen, Köyliö and Kokemäki use images from Henry's legend in their coats of arms.[101]

Today, Henry and his alleged murderer Lalli remain two of the best-known persons from the mediæval history of Finland.[102]

In modern popular culture

The story of Henry's death on the lake is the subject of the song Köyliönjärven jäällä, by Finnish metal band Moonsorrow.[103]

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 Heikkilä 2005, pp. 55–62.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 100.

- ↑ "Pyhän Henrikin muistopäivä". Kirkkovuosikalenteri (in Finnish). Kirkkohallitus, Suomen evankelis-luterilainen kirkko. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Heikkilä 2005, pp. 398–417 In Latin and in Finnish. All 52 known versions of the legend, many of which are fragmented, can also be downloaded from a server of the University of Helsinki.

- ↑ Bishop of Finland was renamed as the Bishop of Turku by 1259, see "Letter by Pope Alexander VI to the Bishop of Turku". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1259. In Latin.

- 1 2 For example, in Bishop Paulus Juusten's Chronicon episcoporum Finlandensium from the mid-16th century (not to be confused with another chronicle of the same name about 100 years earlier), Henry is listed as the first Bishop of Finland without any additional reservations.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 188

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 172.

- ↑ Original text as hosted by the University of Lund. See also Beckman, Natanael (S1886): Medeltidslatin bland skaradjäknar 1943:1 s. 3.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 189.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 234.

- ↑ Nygren 1953, pp. 216–242.

- ↑ The so-called "chancellor bishops of Finland" have been shown to have been a creation of later historians, especially by Juusten in his chronicle of the Finnish Bishops during the 16th century, by Herman Shück in Historisk Tidskrift 2/1963 in his article "Kansler och capella regis under folkungatiden". As to Ragvald and Kettil, the title "chancellor" rests solely on Juustens imagination and is in contradiction with the real and known chancellors of the time. As to Bero, who is mentioned already in the so-called "Palmskölds fragment" probably from the time of Turku bishop Magnus Tavast from the 15th century (dating by Jarl Gallén in "De engelska munkarna i Uppsala – ett katedralkloster på 1100-talet, Historisk Tidskrift för Finland 1976, p.17). According to Schück, Bero might have been the King's chaplain.

- ↑ Kari 2004, pp. 122–123, 132–134.

- ↑ "Letter by the Turku cathedral chapter". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1291. In Latin.

- ↑ "Letter by Pope Nicholas IV". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1292. In Latin.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Suecanum nr.1746. The document (previously dated to 1295–1296) has been shown by Jarl Gallén to be from 22.4.1391 in his article "Studier i Åbo domkyrkans Svartbok" in Historisk Tidskrift för Finland 1978. The same document has been published twice by Hausen, first with false dating in "Registrum Ecclesiae Aboensis" in the year 1890 (nr.18) and then with correct dating in "Finlands Medeltids Urkunder" in 1910 (nr. 999).

- 1 2 Linna 1989, p. 113.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 97.

- ↑ Hausen's Registrum Ecclesiae Aboensis nr.27

- 1 2 Heikkilä 2005, p. 95. See also History of the Cathedral of Turku Archived 2007-08-22 at the Wayback Machine by the Archdiocese of Turku.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, pp. 100, 445.

- 1 2 "Papal letter to chaplain of Nousiainen". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1232. In Latin.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 86.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 116.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 87.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Noteworthy is that king Eric was from Västergötaland, which was a part of the Diocese of Skara.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, pp. 118–125.

- ↑ January 19 was also the memorial of King Canute IV of Denmark who had been canonized January 19, 1101 by Pope Paschal II. Coincidentally, also his relics were translated in 1300, to the Saint Canute's Cathedral in Odense.

- ↑ Archbishop Jukka Paarma's speech on Henry Archived 2006-12-28 at the Wayback Machine. In Finnish.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 80,96

- ↑ Graduale Aboense Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine in The European Library.

- ↑ Kari 2004, pp. 110–112.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 256.

- 1 2 3 4 The Death-lay of Bishop Henry. In Finnish.

- ↑ Werner 1958. Lähteenmäki 1946.

- ↑ Agricola 1987

- ↑ About Bishop Henry by the Lutheran Church of Finland Archived 2007-05-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Heikkilä 2005, pp. 246–256.

- ↑ Linna,1996, pp.151–158.Suvanto 1973.

- 1 2 "Sts Sunniva and Henrik: Scandinavian Martyr Saints"

- 1 2 Article in Tieteessä tapahtuu magazine Archived 2007-07-04 at the Wayback Machine. 2006/8. In Finnish.

- 1 2 3 Heikkilä 2005, p. 253.

- ↑ Linguistic analysis of the poem Archived 2007-07-04 at the Wayback Machine. Provided by the Köyliö Association; in Finnish.

- ↑ See "KESKIAIKA" [MIDDLE AGES]. Archived from the original on 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2006-12-13.; in Finnish. See also description by the National Board of Antiquities of Finland; in Finnish.

- ↑ Description of Bishop Henry's Granary by the National Board of Antiquities of Finland.

- 1 2 Chronicon episcoporum Finlandensium, hosted by the University of Columbia.

- ↑ Delehaye 1955.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 78.

- ↑ Archbishop Johannes. Åsbrink 1935.

- ↑ Bishop Theoderich. See "Estonian Middle Ages". Archived from the original on 2012-08-02. by the Estonian Institute.

- 1 2 Bishop Karl Magnusson. Andresen 2002.

- 1 2 Åsbrink 1935.

- ↑ See Nordisk familjebok- On this page / på denna sida - Sevene ... runeberg.org, accessed 3 May 2021

- ↑ See INCERTI SCRIPTORTS SUECI CHRONICON PRIMORUM IN ECCLESIA UPSALENSI ARCHIEPISCOPORUM (tr. "Sweden's first CHRONICLE IN THE upsalensis Archiepiscopis") In Latin, www.columbia.edu accessed 3 May 2021

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 60.

- ↑ Medieval Anglia docens propaganda wanted to play down the Danish part in the establishment of the Swedish church, often claiming early clergymen to have English heritage or education. Schmid 1934.

- ↑ Bergquist, Anders. Kardinalen som blev påve. 2003. Föreläsning den 15 November 2003. 850-årsjubileum. Kyrkomötet 1153.

- 1 2 Heikkilä 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ Paulsson 1974. The Annales were written in the Sigtuna Abbey. See an article Archived 2007-12-27 at the Wayback Machine by the Foteviken Museum.

- ↑ Saint Botvid in the New Catholic Dictionary Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine. Botvid had been converted to Christianity in England. He was martyred around 1100 in Sweden. Some sources Archived 2007-08-08 at the Wayback Machine claim that he was murdered by a Finnish slave. See also .

- ↑ See . In Swedish.

- ↑ Sigtuna is mentioned as the earlier location of the Uppsala see in a letter by Pope Alexander III to the King Knut Eriksson and Jarl Birger Brosa in the 1170s (Svenskt Diplomatarium I nr 852. Originalbrev).

- ↑ The first Uppland bishops were appointed for Sictunam et Ubsalam in the 1060s. See Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum Archived 2005-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, online text in Latin; scholia 94.

- ↑ Schmid 1934.

- ↑ Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum Archived 2005-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, online text in Latin. See III 53.

- ↑ Linna 1996, pp. 148–207.

- ↑ Papal letters "1209". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14., "1221". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27., "1229". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14., "1232". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14.. In Latin. Diplomatarium Fennicum hosted by the National Archives of Finland.

- ↑ "Letter by Bishop Thomas to his chaplain". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.. In Latin.

- 1 2 Rebane 1989, pp. 37–68. Rebane 2001, pp. 171–200

- ↑ Juva 1964, p. 125.

- ↑ "Letter by Pope Alexander III to the Archbishop of Uppsala". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.. In Latin.

- 1 2 3 Linna 1989.

- ↑ "Letter by Pope Innocent III to the Archbishop of Lund". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14.. In Latin.

- ↑ "Papal letter to King Eric in 1216". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.. In Latin.

- ↑ Note that the letter does not mention the name of the archbishop. However, Valerius had died in 1219 and the Uppsala see was vacant until 1224.

- ↑ "Papal letter to Bishop of Finland". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1221. In Latin.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Suecanum nr.181.

- ↑ Linna, 1996 pp.192–202

- ↑ Läntinen Aarre,Turun keskiaikainen piispanpöytä,Studia historica Jyväskyläensis 16, Jyväskylä 1978 pp113-117.

- ↑ Voionmaa, Väinö, Studier i Ålands Medeltidshistoria, Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistyksen aikakauskirja XXVII, 1916,s 107, Voionmaa, Väinö, Kansallinen raha -ja mittajärjestelmä Suomessa varhaisemmalla keskiajalla, Suomen Museo 1914

- ↑ Ruuth, J.W. Suomi ja paavilliset legaatit 1200-luvun alkupuoliskolla. Historiallinen Aikakauskirja 1909, Ruuth, J.W.,Paavi Innocentio III:en "Ex tuarum" -kirjeestä 30:p:ltä lokakuuta 1209. Saiko Lundin arkkipiispa tämän kirjeen Pohjoismaiden primaksena ja paavillisena legaattina vaiko suoraan arkkipiispana, Historiallinen Arkisto XXII,1,1911,Ruuth, J-W., Några ord om de äldsta danska medeltidsannalerna, som innehålla uppgifter on tågen till Finland 1191 och 1202, Historiska uppsatser tillegnade Magnus Gottfrid Schybergsson, Skrifter utgifne af Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland C, 1911, Ruuth, J.W.,Tanskalaisten annaalien merkintä Suomen retkestä 1191, annaalitutkimuksen kannalta valaistuna., Historiallinen Arkisto XXXIV, 1, 1925. As to the Danish expeditions to Finland see also: Danmarks middelalderlige annaler, udgivet ved Erik Kroman, Copenhagen 1980

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, p. 94. Some historians have proposed that the translation took place already before 1296, or even so late than 1309. The year 1300 is from the mid-15th century Chronicon and remains generally accepted.

- ↑ "Letter by Bishop Thomas to his chaplain". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1234. In Latin.

- ↑ Purhonen 1998. The book contains a thorough comparison of finds from dozens of cemeteries around southwestern Finland.

- 1 2 Heikkilä 2005, p. 108.

- ↑ Heikkilä 2005, pp. 257–61.

- ↑ Kari 2004, p. 135.

- 1 2 See e.g. news by the Turku and Kaarina parish Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. See also article 21.06.2007 Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Anton, Emil (2017). Katolisempi kuin luulit: Aikamatkoja Suomen historiaan. Helsinki: Kirjapaja. p. 14. ISBN 978-952-288-620-0.

- ↑ John Paul II's address to the Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox bishops of Finland, 7 January 1985. In English.

- ↑ John Paul II's letter to Cardinal Joachim Meisner on the 850th anniversary of the arrival of Saint Henry, Bishop, and the 50th anniversary of the founding of the diocese of Helsinki, 17 January 2005. In Latin.

- ↑ ECLA 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ As Heikki, Henrik, Henrikki, Henri. Note that also that the city of Hancock in Michigan, which has a lot of residents of Finnish origins, celebrates "Heikinpäivä" (anglicized Finnish for "Henry's Day") on the same day. See "2007 Heikinpaiva Celebration". Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2007-09-28..

- ↑ See the Catholic Forum Patron Saints Index Archived 2007-06-29 at the Wayback Machine for a description of the ongoing Roman Catholic recognition of Henry.

- ↑ Official www site of the Catholic Diocese of Helsinki.

- ↑ Information about the pilgrimage by the municipality of Köyliö Archived 2007-06-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ecumenical pilgrimage of St. Henry Archived 2007-08-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Nousiainen, Köyliö and Kokemäki coats of arms with descriptions. Maintained by Suomen Kuntaliitto.

- ↑ Klinge 1998.

- ↑ Moonsorrow – Köyliönjärven jäällä (Pakanavedet II) – Genius Lyrics

Cited sources

- Agricola, Mikael (1987), Mikael Agricolan teokset 1, Söderström, ISBN 951-0-13900-9

- Andresen, Lembit (2002) [1997], Eesti Ajalugu I–II. 1997. History of Estonia, AS BIT 2000, 2002, Avita, ISBN 9985-2-0606-1

- Delehaye, Hippolyte (1955), Les légendes hagiographiques. Quatrième édition. Subsidia hagiographica n:o 18A, Bruxelles

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ECLA (2006), Evangelical Lutheran Worship, Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, ISBN 951-746-441-X, archived from the original on 2010-06-21

- Heikkilä, Tuomas (2005), Pyhän Henrikin Legenda, SKS, ISBN 951-746-738-9

- Juva, Einar W. (1964), Suomen kansan historia I. Esihistoria ja keskiaika, Otava

- Kari, Risto (2004), Suomalaisten keskiaika, WSOY, ISBN 951-0-28321-5

- Klinge, Matti (1998), Suomen kansallisbiografia, Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, ISBN 951-746-441-X

- Linna, Martti (1989), Suomen varhaiskeskiajan lähteitä, Gummerus kirjapaino Oy, ISBN 951-96006-1-2

- Linna, Martti (1996), Suomen alueellinen pyhimyskultti ja vanhemmat aluejaot. Vesilahti 1346–1996. Edited by Helena Honka-Hallila, Jyväskylä

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lähteenmäki, Eino (1946), Minkä mitäkin Vesilahden kirkon syntyvaiheista, Vesilahti: Vesilahden seurakunta

- Nygren, Ernst (1953), Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Stockholm

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paulsson, Göte (1974), Annales suecici medii aevi, Bibliotheca historica Lundensis XXXII

- Purhonen, Paula (1998), Kristinuskon saapumisesta Suomeen, Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy, ISBN 951-9057-31-5

- Rebane, Peep Peeter (2001), From Fulco to Theoderic: The Changing Face of Livonian Mission — Andres Andresen (ed.), Muinasaja loojangust omariikluse lävele: Pühendusteos Sulev Vahtre 75. sünnipäevaks, Tartu: Kleio

- Rebane, Peep Peeter (1989), Denmark, the Papacy and the Christianization of Estonia – Michele Maccarrone (ed.), Gli Inizi del Cristianesimo in Livonia-Lettonia: Atti del Colloque internazionale di storia ecclesiastica in occasione dell'VIII centenario della Chiesa in Livonia (1186–1986), Roma 24–25 giugno 1986. Città del Vaticano

- Schmid, Toni (1934), Sverige's kristnande, Uppsala

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Suvanto, Seppo (1973), Satakunnan historia. III : Keskiaika, Satakunnan maakuntaliitto, ISBN 951-95095-0-X

- Werner, Joachim (1958), Kirmukarmu – Monza – Roes – Vendel XIV. (SM 65)

- Åsbrink, Gustav (1935), Svea Rikes Ärkebiskopar, Uppsala

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)