| Sport | Football |

|---|---|

| First meeting | November 13, 1875 Harvard 4, Yale 0 |

| Latest meeting | November 18, 2023 Yale 23, Harvard 18 |

| Next meeting | November 24, 2024 |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | 138 |

| All-time series | Yale leads, 70–61–8 |

| Largest victory | Yale, 54–0 (1957) |

| Longest win streak | Harvard, 9 (2007–2015) |

| Current win streak | Yale, 2 (2022–present) |

The Harvard–Yale football rivalry is renewed annually with The Game, an American college football match between the Harvard Crimson football team of Harvard University and the Yale Bulldogs football team of Yale University.

Though the winner does not take possession of a physical prize, the matchup is usually considered the most important and anticipated game of the year for both teams, regardless of their season records. The Game is scheduled annually as the last contest of the year for both teams; as the Ivy League does not participate in postseason play for football, The Game is the final outing for each team's graduating seniors. Some years, the rivalry carries the additional significance of deciding the Ivy League championship.

The weekend of The Game includes more than just the varsity matchup; the respective Yale residential college football teams compete against "sister" Harvard house teams the day before.[1] The Game is third among most-played NCAA Division I football rivalries. Yale leads the series 70–61–8.

"Harvard and Yale generally duke it out in the academic arena",[2] but geographic proximity, the history of Yale's founding[3][4] and social competition between the respective student and alumni bodies animate the athletic rivalry.

Harvard football head coach Joe Restic, who held the position for 23 seasons, quipped regarding his relationship with retired Yale football head coach and National Football Foundation/College Football Hall of Fame member Carm Cozza, who held the position for 32 seasons: "Each year, we're friends for 364 days and rivals for one." The athletic rivalry is historically the second in American intercollegiate athletics, with Rutgers vs Princeton being the first, having played the first ever college football game.[5][6]

The signature Harvard fight song, "Ten Thousand Men of Harvard", names Yale in the famous final stanza.[7] The song is sung in the Harvard football locker room after a victory regardless of the opponent.[8] The song is among six Harvard fight songs that mention Yale.[9] "Down the Field" is Yale's signature fight song and Harvard is the named foe. The song is among five that mention Harvard. Two of the songs, "Bingo, That's the Lingo" and "Goodnight, Harvard", have been sung substituting Princeton for Harvard when appropriate. Cole Porter composed the former and Douglas Moore the latter.[10]

The football rivalry is among the most admired rivalries on the American athletic scene. The schools and the rivalry established the template for American college football. The Game is the most prominent athletic contest between the schools and has accounted for many of either rival's best-publicized athletic feats.[11][12][13] Sports Illustrated (College Edition) rated the athletic rivalry sixth-best among American athletic collegiate rivalries behind, in order, Alabama–Auburn, Duke–North Carolina, UCLA–USC, Army–Navy and Cal–Stanford. The football rivalry was ranked 8th among Athlon Sports's top 25 rivalries in the history of college football.[14]

Significance

"A whale-ship was my Yale College and my Harvard" from Moby-Dick by Herman Melville examples public fascination beyond athletics with both institutions.[15] Twelve past presidents of the United States have earned an undergraduate or professional degree from one of the universities. The list includes: John Adams, John Quincy Adams, George Herbert Walker Bush, George Walker Bush, Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford, Rutherford B. Hayes, John F. Kennedy, Barack Obama, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.

Theodore Roosevelt, a fan of football, is considered often the savior of football in the early 20th century. Roosevelt, who attended the second Harvard–Yale game as a first year student at Harvard College in 1876, has been quoted, "In life as in football, the principle to follow is hit the line hard".[16] Roosevelt suggested turn-of-the-century "manly virtues" were taught and reinforced on the gridiron.

Walter Camp, captain of the 1878 and 1879 Yale football teams, is considered often "the father" of American football and its most ardent popularizer. Camp attended almost every important rule committee meeting for the sport to his death in 1925 while napping between sessions of the Intercollegiate Football Rule Committee. Camp attended a rules meeting for the sport when he was a student at Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut. Camp wrote professionally about the sport, popularizing All-American teams with Caspar Whitney for This Week's Sports magazine. Eventually Collier's magazine featured the annual selections.

The rivalry has been noted in American athletic and popular culture. The University of Mississippi's first football team, organized by Alexander Bondurant, adopted Yale blue and crimson for team colors in 1893.[17] Newspapers printed Bull Tales, Garry Trudeau's collegiate precursor to Doonesbury published in the Yale Daily News, often featuring Brian Dowling and Calvin Hill, in the run-up to the 1968 Yale vs. Harvard football game.[18] Burns, Baby Burns, the fourth episode in the eighth season of The Simpsons, depicts Mr. Burns returning to Springfield, Massachusetts after attending The Game.

Thomas G. Bergin, better known for commentary on The Divine Comedy and longtime Sterling Professor of Romance Languages at Yale University, authored THE GAME: The Harvard Yale Football Rivalry 1875 – 1983, published in 1984.

Owen Johnson's Dink Stover, Gilbert Patten's Frank Merriwell and F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tom Buchanan played football for Yale.

Historical significance

The first contest was held in 1875, two years after the inaugural Princeton – Yale football contest. Harvard athlete Nathaniel Curtis challenged Yale's captain, William Arnold to a rugby-style game.[19][20] The next season Curtis was captain.[21] He took one look at Walter Camp, then only 156 pounds, and told Yale captain Gene Baker "You don't mean to let that child play, do you? . . . He will get hurt."[22][23]

The Harvard-Yale series is the third most played rivalry in collegiate football history, including 137 games since 1875. In the series, Yale has 69 wins, Harvard has 61 wins, and the teams have tied eight times.[24] Only two collegiate rivalries have played more often than Harvard-Yale. Princeton and Yale have played 143 times since 1873, and Lafayette College and Lehigh University (known simply as "The Rivalry"), have played the most, 157 games, dating back to 1884.

Yale and Harvard have played major roles in advancing and shaping intercollegiate athletics. The first American intercollegiate sporting event took place August 3, 1852 after Yale invited Harvard to a race of crews. The first intercollegiate contests in ice hockey, soccer or five-on-five basketball contests featured teams from Harvard and Yale.[25] Many now century-old aspects of American football were introduced by Harvard or Yale students or athletes. Yale introduced cheerleading at athletic events in 1890.[26] Harvard introduced spring practice to collegiate football March 14, 1889.[27] Yalies sang "Hold the Fort" during the 1892 Harvard game, considered the first public performance of a collegiate "fight song".[28]

Reform and Roosevelt

Years later, representatives from Harvard, Yale and Princeton were summoned to the White House October 9, 1905 by Theodore Roosevelt to discuss reforms to mitigate unnecessarily violent, unsportsmanlike play and minimize resultant fatalities and injuries in football. Roosevelt sought reform of rules to quell misgivings about the sport he admired. The New York Times, Harper's, McClure's and Nation advocated reform if not abolishment of the sport. The era's Progressives, muckrakers, university faculties and presidents—particularly at Harvard, led by its president, Charles W. Eliot and NYU, led by its president Henry MacCracken—and the general public had misgivings about the sport's safety and place in higher and secondary school education. Walter Camp, Bill Reid, and Arthur T. Hillebrand attended the meeting, representing respectively Yale, Harvard and Princeton.[29]

The "Grim Reaper Smiles on the Goalposts" cartoon, published December 3, 1905 in the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune depicting the Grim Reaper sitting on the crossbar of a goalpost overlooking a mound of uniformed dead bodies exhibited how the press presented the problem. November 25 Union College halfback Harold Moore was knocked unconscious in a game versus NYU. Moore, age 19, died of a cerebral hemorrhage six hours later. MacCracken called a meeting of university leaders to suggest protective gear be worn by the athletes.[30] Reformers requested deemphasis or suspension of the sport. The press reported that 18 athletes, 15 of whom were high school students,[31] died from football-related injuries during the 1905 season. The era has been described as the "first concussion crisis" for the sport.[32]

A meeting convened December 28, 1905 with 62 schools represented to appoint a rules committee. January 12 the American Football Rules Committee met. March 31 the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States was established, the corporate forerunner to the NCAA.[33]

Rules were changed: the flying wedge was banned, the neutral zone was created, and the distance increased to ten yards from five yards for a first down.

Council of Ivy Group Presidents

Decades later the eight universities that administer athletic programs and competition under the auspices of the Council of Ivy Group Presidents, better known as the Ivy League, reiterated reforms rooted in requests made during the series of meetings.[34][35] Agreements among the athletics departments at Harvard, Yale and Princeton in 1906, 1916 (the "Three Presidents Agreements" on eligibility), and a revision of that agreement in 1923 have been considered precursors to the Ivy Group Agreement, each agreement addressing amateurism and college football.

The Ivy Group Agreement, adopted in 1945, states for football, "the players be truly representative of the student body and not comprised of a group of special recruited and trained athletes."[36] Harvard president Nathan Pusey and Yale president A. Whitney Griswold collaborated closely toward the eventual implementation of the Ivy League in 1954 with the "Agreement" extended to all sports.[37] Round-robin play started in 1956 for football among programs representing Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Princeton University, University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University.

Game results

| Harvard victories | Yale victories |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

† The 1881 game is recognized by both teams as a Yale victory due to four fewer safeties.[38][39]

‡ Hosted ESPN's College Gameday.[40]

All games since 1956 are Ivy League contests. The teams did not play in 2020 due to the Ivy League cancelling the 2020 football season because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[41]

Regular season overtime was introduced for Division I-AA in 1981[42] and was first used in the 2005 game.

Stadiums

The contests are hosted in stadiums listed on the U.S. National Register of Historical Places and are U.S. National Historic Landmarks. They are among the oldest gridiron football stadiums.[43]

Yale Bowl

Designs for the Rose Bowl and Michigan Stadium were influenced by the Yale Bowl Stadium. When the Bowl was built by Charles Ferry in 1914 the Colosseum of Pompeii in Italy was the only other known structure in the world engineered by digging a hole then using the displaced dirt to build the surrounding wall or berm. The Bowl had the largest seating capacity for a stadium in the world upon completion of construction. Head coach Carm Cozza likened the feeling of running through the tunnel onto the Bowl to a gladiator entering the arena.[44][45]

The Yale Bowl, completed before World War I, presaged a collegiate stadium-building blitz associated with the game's popularity in the Roaring Twenties. The modern era of college football, with radio broadcasts coast to coast of gridiron exploits by Red Grange or the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame, began soon after the construction of stadiums that rivaled the Yale Bowl's seating capacity.[46][47] The Rose Bowl venue, its annual post-season contest, and the plethora of venues and post-season football contests known as "bowls" has been attributed to the Yale Bowl.[48][49]

Walter Camp had been the long-tenured treasurer of the Yale Athletic Union, precursor to the later professional athletic department administration. Yale swim athlete and team manager Robert Moses—acknowledged later in life as the power broker of urban planning and a "master builder"—had disagreements with Camp regarding the Athletic Union's treasury. Moses wrote editorials in two campus papers and lobbied Camp and the administration for larger sums for the minor sports (every sport save football, rowing and hockey) from the fund swelled by football receipts. Camp conceded little. Camp's big idea was to fund eventually the Yale Bowl Stadium.[50]

The Walter Camp Memorial Arch greets visitors to the Walter Camp Fields on Derby Avenue in front of the Bowl. A seven-person committee, including Yale Law School Dean Robert Hutchins, who would later abolish a storied football program at University of Chicago, raised money for the arch from a variety of sources, including 224 colleges and universities, and 279 high schools and prep schools.[51][52]

Harvard Stadium

Harvard Stadium, was built in 1903. The 25th Anniversary Reunion gift by the Harvard Class of 1879 funded the project.

The stadium is the nation's oldest permanent concrete structure dedicated to intercollegiate athletics. The stadium mimics the Panathenaic Stadium. Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and first president of the Harvard Club of Boston, donated the land, known as Soldier's Field, for a memorial to Harvard men who were killed during the American Civil War.

Camp accommodated Harvard on the issue of widening the playing field to "open up" play from the almost perpetual rugby scrum that characterized the sport. The rules reform movement, which gained impetus after the 1905 meeting at the White House, demanded action. The present standardized playing field width was as wide as could be accommodated in Harvard Stadium, the first football stadium constructed with reinforced concrete and a pioneering execution in the construction of large structures. The forward pass was adopted instead of an even wider field. The rule change is mentioned often as the most important in the history of the sport. John Heisman championed the forward pass and is credited with lobbying successfully influential members of the IIAUS American Football Rules Committee to adopt the change.[53][54][55]

Notable contests

1875

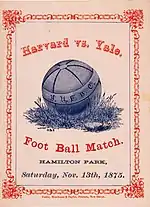

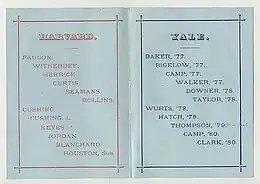

The game, a rugby contest in fact but called "Foot Ball",[56] played November 13 in New Haven at Hamilton Park was won by Harvard.[57] The "Foot Ball Match" was played under "concessionary rules". Harvard conceded to aspects of the soccer-like "Foot Ball" played by Yale while Yale conceded likewise to Harvard's rugby-informed play, featured in the Harvard–McGill game of 1874.[58]

The contest has been noted as the first ever when both teams donned coordinated uniforms. The teams fielded fifteen athletes to a side.[59] Through plebiscite, Harvard students picked crimson over magenta as the school color and athletic nickname.[60]

Yale would win consecutively ten games and tie once before Harvard would win again, 12–6 in 1890, a season Harvard claimed a national championship.[61] Harvard's record in the series was once 9–23–5 through the start of World War I.[62] "Harvard felt a certain loss of manhood in not winning a single football game with Yale in the eighties and only to win one in the nighties," historian Samuel Eliot Morison noted in Three Centuries of Harvard 1636–1936.[63]

1876

The 1876 game was the first won by Yale, and the first game Walter Camp played in. Eugene V. Baker was the captain. O. D. Thompson scored on Harvard.[64]

1887

On November 24, the year's Thanksgiving holiday, Yale defeated Harvard, 17–8, at the Polo Grounds in New York City before 18,000 spectators. Harvard had yielded six points total the entire season. For the third time in the brief history of the rivalry both squads sported undefeated and untied records. William H. Corbin, the 1888 team captain and future Yale head coach known as "Pa" Corbin, is credited with leading Yale to the victory and a 9–0 record, with Harvard's season ending with a 10–1 record.[65] The game ball was discovered and picked up by an oyster boat in the water in March 1890 and returned to Yale.[66]

1890

The1890 game was played on November 22 at Hampden Park in Springfield, Massachusetts. Harvard ended the season undefeated and untied, 11–0, defeating Yale, 12–6. Yale finished the season with a 12–1 record. The victory is considered possibly the greatest in the history of Harvard Crimson football and Arthur Cumnock, team captain, as Harvard's greatest football player. Harvard won its second game in the series and ended a streak that included one tie and ten losses.

Cumnock, who captained the 1889 and 1890 Crimson teams, is credited with convening the first spring practice in collegiate football.

1891

The 1891 game was held on November 21, again in Springfield, again with Harvard and Yale undefeated and untied for the contest; Yale won 10–0. Yale finished the season with a 13–0 record. Harvard, nursing a 23-game win streak over two seasons, ended the season 13–1.

The play of the game was a fumble returned for a touchdown by Laurie Bliss. Frank Hinkey separated Crimson back Hamilton Forbush Corbett from the ball that Bliss retrieved on the fly.[67]

1892

Harvard introduced the flying wedge to football November 19 at the beginning of the second half before 21,000 spectators.[68] Captain Vance McCormack warned his Yale teammates upon witnessing the formation, "Boys, this is something new but play the game as you have been taught. Keep your eyes open and do not let them draw you in".[69]

Lorin F. Deland, an unpaid adviser to the Harvard team and an avid chess player, suggested the tactic. Yale won, 6–0.

The flying wedge was outlawed two years after its introduction. Bergin writes, "The legacy of the wedge is perceptible in the austere rules of today's game, by which a 'man in motion' can run away from the line literally, but if he takes a step forward before the ball is snapped his team is penalized. Offensive lineman must not move a muscle or even turn their heads before the snap."[70]

Deland would coach Harvard for three games in 1895 and co-author with Walter Camp the seminal Football published in 1896.[71][72]

Mass-momentum plays based on the flying wedge were the rage in the sport. The result was mayhem that eventually prompted intervention in 1905 by Teddy Roosevelt to help reform rules governing play.[73]

1894

Held on November 24, Yale won the 1894 game 12–4, at Hampden Park.[74][75] The contest, a bloody mess of a game, was known for on-field and off-field violence. In an era before players employed protective equipment of any type, the result of rough play was a given; however, competition between the Yale and Harvard football programs was placed on hiatus, seven players denoted in "dying condition" after the contest, according to the German daily newspaper Munchener Nachrichten.[76]

Frank Hinkey has been alleged to have broken the collarbone of a Harvard player following a fair catch.[77] Yale tackle Fred Murphy broke the nose of Harvard's Bob Hallowell during an official's conference; in turn, Murphy absorbed a hard hit later in the contest that hospitalized him. Rumors circulated post-game he died in a local hospital. Violence ensued among fans in the streets of Springfield.[78]

The Harvard faculty voted by a two-to-one margin to abolish football. Harvard president Charles W. Eliot supported the faculty.[79] Eliot opined, "Football is to academics what bull fighting is to agriculture".[80]

The Harvard Corporation sided, however, with alumni and students who championed the sport.[81] The Harvard Board of Overseers invited Camp to chair an investigative committee to determine the extent of "character-building" as well as "brutality" on college and prep school football fields. Rev. Joseph Twichell, Endicott Peabody and Henry E. Howland were among the committee's members.[82]

Ray Tompkins, a former teammate of Camp as well as a two-time captain at the guard position,[83] confided to Camp during the crisis of '94 that football was too American to be abrogated by any one or more faculty.[84] Tompkins later would be namesake to the building, Ray Tompkins House, that serves as the administrative headquarters for Yale athletics.[85]

Yale and Harvard took a two-year hiatus on the football rivalry. The programs have played annually ever since excluding the World War I and World War II years and in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1898

On the November 19 game, two future members of the National Football Foundation/College Football Hall of Fame showcased apt athletic and leadership ability, leading Harvard to a 17–0 victory. Both would later coach the Crimson. Bill Reid, a fullback, scored two touchdowns versus Yale. Harvard achieved a rare victory in the series, its third in 19 contests. Reid was rewarded with his picture published in Harper's Weekly.[86] Percy D. Haughton was on the gridiron, too, for the Crimson.

The now traditional end of season scheduling started this date and continues to the present.

1900

On November 24 in Orange, Connecticut at Yale Field, the undefeated and untied Harvard and Yale teams met once more, with Yale winning 28–0. Gordon Brown, a four-time first team All American at the guard position, captained a team that held eleven of thirteen opponents scoreless.

1903

On November 21, Harvard hosted Yale at Harvard Stadium for the first time. Yale won, 16–0, before an estimated crowd of 40,000.

Harvard opened the facility with a game versus Dartmouth the week before.

1905

November 25 was the conclusion of another undefeated, untied season for Yale. An estimated crowd of 43,000 at Soldiers Field witnessed a 6–0 Yale win and enough violent play to prompt the delivery of a note from the benefactor who donated to Soldiers Field to Harvard, Henry Lee Higginson, to Crimson head coach Bill Reid. The note requested the withdrawal of the Crimson team from the playing field; Reid ignored the request.

Bob Forbes was the only player to cross the goal line.

Harvard finished the season 8–2–1, Yale 10–0.[87]

1908

The game played November 21 marked the end of a six-game winning streak for Yale. Harvard won, 4–0, on a field goal by Victor Kennard, a fullback, at Yale Field in Orange, Connecticut. Hamilton Fish III, captain of the 1909 team (and acting captain 1908 when that year's captain was injured) was a mainstay at tackle the 1907–1909 seasons.

Percy Haughton, Harvard's first professional coach, was understood to had strangled to death a bulldog during the pregame pep talk. This contest was his first as a head coach versus Yale. Contemporary research concludes that at worse Haughton "strangled" a papier mache bulldog and tied another such creation to the back fender of his automobile.[88]

1909

On November 20 in Boston, Harvard and Yale competed for the national championship. Ted Coy captained the Yale squad which shutout Harvard, 8–0. Coy threw a touchdown pass and Harvard didn't advance pass the Yale 30 yard line the entire contest. Harvard fielded two future NFF/College Football Hall of Fame members, Bob Fisher—a future head coach for the Crimson—and Hamilton Fish. The pair were respectively right guard and right tackle on offense. Their coach Percy Haughton also would win election to the Hall of Fame.

Harvard would dominate the series from 1909 to 1922, earning an 8–1–2 record.[89]

1914

The game played on November 21 was the inaugural event at the Yale Bowl. William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt were said to be among the spectators, a throng estimated at between 70,000 and 74,000.[90] Harvard won, 36–0.

The day's memorable play was a 98-yard touchdown run after a recovered fumble by Jeff Coolidge. Coolidge gathered the Yale fumble with Harvard leading by two touchdowns.[91]

"Yale has the Bowl but Harvard has the punch" was reportedly repeated often in the press the next day.

1915

On November 20, Harvard defeated Yale 41–0, the program's largest margin of victory in the series. Team captain Eddie Mahan scored 4 touchdowns and kicked five extra points.

The week before the Yale game and subsequent to the Brown game, won 16–7 by Harvard, William J. Bingham, a track star and team captain, authored an announcement under byline in the November 15 issue of the Harvard Crimson.[92] Bingham thought poorly of the cheering and singing among students at the Brown game and announced a pep rally for Thursday to support Mahan and head coach Haughton before the Yale game. Bingham was appointed Harvard's first athletic director a decade later. He held the position 1926–1951.[93] Harvard's most prestigious athletic award is named in his honor, the winner announced at the Harvard Varsity Club's annual Senior Letterwinner Dinner.[94]

1919

Harvard coach Bob Fisher's team concluded an undefeated regular season November 22 with a 10–3 victory at the Stadium before an estimated crowd of 50,000.[95]

Arnold Horween, who would later coach the Crimson, kicked a field goal and Eddie Casey scored on a reception in the first half. Robert Sedgwick helped anchor an outstanding offensive and defensive line that day and throughout the season. Only one touchdown was scored against Harvard during the season.[96]

Harvard won later the 1920 East–West Tournament Bowl, now known as the Rose Bowl, versus the Oregon Webfoots, now known as the Oregon Ducks, 10–7.

1920

Harvard dominated completely Yale at the Bowl, 9–0, before an estimated crowd of nearly 80,000. Charles Buell kicked two field goals and Arnold Horween kicked one while Harvard controlled the line of scrimmage. The Harvard team outrushed its Yale counterpart 195 yards to 68 and outpassed it 124 yards to 43. Buell quarterbacked the national champions.[97]

1923

On November 24, the game was played on, according to Grantland Rice, "a gridiron of seventeen lakes, five quagmires and a water hazard" in Boston.[98] Yale won, 13–0. Ducky Pond, future Yale head coach and All American for the season, returned a fumble 67 yards for a touchdown, Yale's first touchdown versus Harvard since World War I.[99]

Yale head coach T.A. Dwight Jones, future member of the College Football Hall of Fame, advised before the opening kickoff, "Gentlemen, you are about to play Harvard. You will never do anything else so important for the rest of your lives."[100] Yale, who defeated Army and then Princeton at the Yale Bowl before crowds of an estimated 80,000 and ended the season scoring 230 points and yielding 38, entered the contest with claim to the national championship. "Memphis" Bill Mallory, Century Milstead and Mal Stevens contributed to the victory.[101] Bill Mallory, team captain and future member of the College Football Hall of Fame, kicked two field goals in the third quarter to complete the scoring.[102]

The Yale athletics department awards a prize commemorating Mallory, who died in a plane crash while serving in the Army Air Forces in World War II, to "the senior man who, on the field of play and in his life at Yale, best represents the highest ideals of American sportsmanship and Yale tradition". The winner is announced at Class Day.

The 1956 Yale Banner, the senior class yearbook, published, "Bill Mallory was, to put it mildly, an all-around football player. He backed the line sharply, ran effectively, kicked field goals with unbelievable skill, and blocked flawlessly. It was his leadership, perhaps, more than any other factor, that brought Yale its last undefeated, untied season."[103] The 1960 Yale football team would duplicate the feat.

1925

On November 21, the game, between a 5–2 Yale team and a 4–3 Harvard team, ended in what the Harvard Crimson hailed as "a scoreless victory." T.A.D. Jones's charges couldn't decide what play to call on the Harvard one-foot line against Bob Fisher's defense as time ran down in the fourth quarter.[104]

Yale was in "scoring position" six times over the course of the contest but never crossed the goal line.[105] This game is the last scoreless tie in the series.

1931

The November 21 contest showcased the final gridiron competition between Yale captain Albie Booth and Harvard captain Barry Wood, who lettered three times each in football, ice hockey and baseball.

Harvard was undefeated at 7–0. Yale was 3–1–2. Booth kicked a late fourth quarter field goal, the sole points scored.

1932

The November 19 game was played for 35,000 to 50,000 fans at Yale Bowl, including Babe Ruth, a "loyal Crimson fan" among them, who endured an unreleting rain off Long Island Sound. Walter Levering and Walter Marting scored touchdowns and Yale shut out Harvard 13–0.[106][107][108] Walter Marting's son, Walter Marting, Jr., known as Del, would win varsity letters three seasons in the sixties and participate in the rivalry's historic 1968 contest.[109]

1936

On November 21, Yale won, 14–13, at the Bowl. Heisman Trophy winner Larry Kelley captained the squad. Future Heisman trophy winners Clint Frank and Kelley collaborated on a 42-yard pass play, Kelley scoring, to forge a 14–0 halftime lead. Harvard missed an extra point in the fourth quarter and Yale held on for the win.[110] Yale, with a 7–1 record, was ranked 12th in the final AP Poll.[111]

1937

On November 20 Harvard won, 13–6, through snow flurries at the Stadium. The teams rushing attacks totaled 434 yards. Harvard's Torbert Macdonal, who would captain the 1939 Crimson team, gained 102 yards on 10 carries. Yale's Al Hessberg gained 98 yards on 15 carries. Clint Frank scored on a one-yard run in the third quarter.[112]

Yale's second Heisman Trophy winner played with a severe injury most of the contest but made "fifty tackles" according to Stanley Woodward, the sports journalist credited with the first printed mention of the "ivy colleges" or Ivy League, of the New York Herald Tribune.[113] Woodward hailed Frank "the best football player we have seen" since World War I.[114] The Yale team finished 12th in the final AP Poll ranking.

1941

November 22 was Harvard senior Endicott Peabody II's final performance versus Yale. Peabody started three straight seasons on the offensive line. Harvard rushed from scrimmage for 270 yards, Don McNicol accounting for 179 yards and a touchdown on 25 carries.[115]

Harvard shut out Yale, 28–0, in 1940, and shut out Yale, 14–0, in 1941.

Peabody finished sixth in the balloting for the season's Heisman Trophy,[116] and would later serve a term as Governor of Massachusetts.

1949

On November 19, Yale won, 29–6, led by Levi Jackson, its first African-American captain. Jackson was born in Branford, Connecticut and reared in New Haven where he was a graduate of Hillhouse High School. Jackson had been a sergeant in the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps during World War II before matriculating at Yale.

Jackson scored the day's first and second touchdowns.

- 1952

On November 22, Yale won, 41–14, at the Stadium. The box score noted Charley Yeager scored Yale's 41st point on a pass reception, from the holder. (Conversions were worth one point, kicked, ran or passed in that era.) Yeager, who stood 5 feet, 5 inches and weighed 145 pounds, was Yale's head football manager. Yeager wore a pristine jersey numbered 99 as he scored on a squareout route, flanked right.

Life, Time and Saturday Evening Post reported the Walter Mittyesque feat in subsequent issues. At the time rumblings were heard that Harvard might cease fielding a football team.[117]

1955

The November 19 game was won by Yale, 21–7. Ted Kennedy, in jersey numbered 88, caught a pass for a touchdown in the third quarter for Harvard's sole touchdown in New Haven on a snowy day before a crowd that included his brother, Senator John F. Kennedy, Connecticut's governor Abe Ribicoff and New York City's mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr.[118] Denny McGill scored Yale's 20th point on an interception. Offensive tackles Phil Tarasovic, the team captain, and William Post Lovejoy, winner of the Mallory Award for the Class of 1956, helped Yale running backs Gene Coker, Al Ward and Denny McGill gain 238 rushing yards on 45 carries. Harvard, in turn, was held to 78 rushing yards on 33 carries.[119][120]

Charley Yeager was recalled as fondly as he might be by Harvard denizens of the Dillon Field House. "Remember Charley Yaeger" was chalked prominently in block letters on the Harvard athletics center during the week leading up to Yale's win.[121]

Crimson coach Lloyd Jordan, a future member of the College Football Hall of Fame, was replaced by John Yovicsin in the off-season.

1956

On November 24, Denny McGill gained 116 yards on 8 carries and scored on runs of two and seventy-eight yards to stake Yale a 14–0 lead.[122] Play turned unsportsmanlike toward the end of Yale's 42–14 rout, clinching the inaugural Ivy League football title.[123]

The Ivy League athletic conference became fully operational in 1956. Yale won the first Ivy League football title with an undefeated, untied record playing a round-robin schedule versus Harvard, Princeton, Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth and Penn.

1957

On November 23, Harvard first year head coach John Yovicsin, recommended by Dick Harlow,[124] brought his team to New Haven with an injured starting quarterback. Yale lead 34–0 by halftime; the Harvard Class of 1947 dispatched a telegram to Yovicsin's counterpart, Jordan Olivar, to "Please" take it easy on the Crimson in the second half. Yale scored 20 points to complete the scoring.[125]

Including this contest, the Crimson would enjoy a 35–24–1 record versus the Bulldogs over the next six decades under three head coaches, Yovicsin, Restic and Murphy. By contrast, the Yale program had six coaches during the period, four during Murphy's career at Harvard.

1960

Mike Pyle, future Chicago Bears center and NFL All-Pro, captained an undefeated, untied Yale team to the 1960 Ivy League football title, 14th place on the AP Poll, and a share of the Lambert Trophy after Yale routed Harvard, 39–6, on November 19. Pyle, who would captain the 1963 NFL Championship–winning Bears, lead the last untied and undefeated Yale team since 1923.

Yale's first play from scrimmage netted a 41-yard touchdown run by Ken Wolfe. Harvard quarterback Charlie Ravenal turned over a pitchout that John Hutcherson returned 42 yards for a touchdown early in the afternoon. Harvard scored with Yale leading, 39–0.[126]

1963

The game played November 30, which Yale won, 20–6, was postponed from November 23 in mourning for assassinated president of the United States John F. Kennedy, Harvard College Class of 1940 and Yale University 1962 honorand and commencement speaker.[127] Arrangements had been made during the week by the Secret Service for Kennedy to attend the contest at Yale after the trip to Dallas.[128] Kennedy had earned a JV football letter at Harvard.[129] Chuck Mercein lead all running backs with 63 total rushing yards and made 2 of 3 PATs.[130]

1967 and 1968

"The games played in 1967 and 1968 were a pair of back-to-back thrillers unique in the chronicles. Both were filled with action, great individual efforts, and costly misplays, each terminating in breathtaking climaxes ... each had the outline of high melodrama," Tom Bergin wrote the above in his definitive The Game: The Harvard-Yale Football Rivalry, 1875–1983.[131]

Yale won, 24–20, on a soggy playing surface under clearing skies on November 25, 1967, at the Yale Bowl. A crowd of 68,315, understood as the largest crowd to attend a football game in the Ivy League era, was present.[132]

Yale scored first on a recovery in the endzone. Offensive end Del Marting scored. The second score, off a lengthy improvisational quarterback scramble by Dowling, was a 53-yard pass completion to Calvin Hill. Hill remarked to Dan Jenkins, reporting for Sports Illustrated, "We do that a lot. It's kind of a play. Dowling gets in trouble and I wave my hand and he throws it to me."[133] A fieldgoal was the 17th point. Then, Harvard scored three touchdowns, one each in the second, third and fourth quarters. Harvard, led by left handed quarterback Ric Zimmerman, Vic Gatto (next year's captain) and Ray Hornblower, overcame a seventeen-point Yale lead to score twenty unanswered points. Then, late in the fourth quarter Dowling delivered deftly a 66-yard pass to Del Marting for the winning touchdown. Yale claimed the victory soon after Ken O'Connell fumbled on Harvard's next series.

The game played November 23, 1968, was highlighted by the Crimson scoring 16 points in the final 42 seconds to tie a highly touted Bulldog squad. Harvard All Ivy punter and Harvard Varsity Club Hall of Fame member Gary Singleterry has recalled that the 1968 game and season was a triumph of the human spirit for Harvard football.[134]

Harvard head coach John Yovicsin substituted twice quarterback Frank Champi—number 27, the man of the moment who earned one varsity H at Harvard[135]—for George Lalich to reignite the Crimson's nearly-extinguished offense. Champi singed the Yale defense at the close of the first half with a touchdown drive (however, Yovicsin returned Champi to the bench at the start of the second half), then Champi, again substituting for the lackluster Lalich, immolated the Yale defense in the closing minutes of the contest. Yale lost six fumbles, an all-time record, adding logs to the fire.[136]

Poor officiating and poor timekeeping contributed to the outcome, Yale partisans and players have suggested; nonetheless, Pete Varney, who would later play in the MLB, ran a slant route and caught a pass right in front of Yale linebacker Ed Franklin, giving Harvard its 29th point.

Yale had a 16-game winning streak. Both teams were 8–0. For the first time since 1909, both adversaries were undefeated and untied for the contest. Yale was ranked at the lower end of a few top national college football polls. Calvin Hill, soon to be the first ever and only Ivy League football athlete selected in the first round of the NFL draft, and Tommy Lee Jones, an offensive guard for Harvard, were in uniform.[137][138]

The Penn Quakers finished third in the standings and won five League games by close scores but were defeated by Harvard, 28–6, and Yale, 30–13.[139] By contrast, Yale had defeated, in order, excluding the Penn game—which was Yale's fifth win in the League—Brown, 35–15, Columbia, 29–7, Cornell 25–13, Dartmouth, 47–27, and Princeton, 42–17.[140]

The Yale roster included two future Rhodes Scholars, Kurt Schmoke and Tom Neville, who would later captain a Yale football squad. The Harvard roster included one future Rhodes Scholar, Paul Saba.

The outcome inspired The Harvard Crimson to print the logically impossible "Harvard Beats Yale, 29–29" headline.[141] This headline was later used as the title for a 2008 documentary about this Game, directed by Kevin Rafferty.[142]

Yale Daily News editors headlined "Johns Stage Dramatic Rally Tie Elis For Title, 29 – All" at top right half of frontpage of its November 25, 1968 issue.

John T. Downey, a Yale football letterwinner before joining the CIA, was a prisoner-of-war in 1968. His Chinese captors allowed correspondences from home while he endured solitary confinement. Downey received from a friend a postcard announcing Yale had won, 29–13. Months later he learned of the "loss".

1969

On November 22, Yale outlasted Harvard, 7–0, and shared the League football title with Dartmouth and Princeton. Each team suffered one loss.

Future NFL defensive back and coach Don Martin and Bill Primps, who scored the sole touchdown, combined for 162 rushing yards.[143] Captain Andy Coe lead the defense to the shutout. Harvard's offense help preserve the shutout. The unit advanced to the Yale ten yard line in the last few minutes of the fourth quarter but missed anticlimactically a 32-yard field goal attempt moments before game time expired.[144]

1972

In Boston on November 25, Yale overcame a 17–0 Harvard second quarter lead with 28 unanswered points. Yale won, 28–17.

Dick Jauron, who rushed for 183 yards, setting the all-time record in the series,[145] and captain Dick Perschel, at linebacker, lead the Bulldogs to the come-from-behind victory. Harvard's Ted DeMars rushed for 153 yards, including an 86-yard first quarter touchdown. Harvard was held scoreless after quarterback Eric Crone's one-yard touchdown run and the successful conversion kick. Momentum swung away from Harvard after fumbling on its one-yard line later in the quarter. Tyrell Henning scored eventually for Yale. Momentum swung seemingly further toward Yale when a Harvard punt was blocked on the subsequent set of downs; however, Jauron was stopped at the 1-yard line before halftime. Jauron scored on a seventy-four run early in the third quarter.[146]

Jauron, among a myriad of awards, won the Gridiron Club of Greater Boston George H. "Bulger" Lowe award for the season.[147]

1974

On November 22, Harvard Stadium was the setting for a late fourth quarter 95-yard drive that defeated an undefeated and untied Yale team. Senior quarterback, first year starter and eventual All Ivy First Team football selection Milt Holt lead the Harvard offense to the winning touchdown through a Yale defense that lead the League in many statistical categories. Holt scored on a sweep around left end for Harvard's 20th point. The Crimson won, 21–16. Harvard and Yale both finished the season 6–1 in the League and shared the title.

Gary Fencik caught 11 passes for 187 yards in the losing effort.[148] Fencik was one of a total of six varsity letterwinners on the field—with Yale teammates Elvin Charity and Vic Staffieri (whom Carm Cozza described as "the best captain I ever had" when Staffieri lead the 1976 Bulldogs team),[149] and Bill Emper, Dan Jiggetts, and Pat McInally for Harvard—who were named later to the Ivy League Silver Anniversary team. Greg Dubinetz, a Yale senior lineman, was drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals in the ninth round of the 1975 NFL draft and enjoyed a brief professional football career.

1975

The game played November 22 in New Haven—the outcome elevating Harvard to its first undisputed League football championship (it had shared titles three other seasons since 1956, the League's first year) – featured future Chicago Bears teammates Harvard captain Dan Jiggetts and Yale captain Gary Fencik. Fencik helped win Super Bowl XX and a Gold Record with the Bears.

Harvard won, 10–7, on a fourth quarter field goal by Mike Lynch with 0:33 on the official time clock.

1978

Future three-time Super Bowl champion Kenny Hill ran well from the I formation, 154 yards on 25 carries, and scored down a sideline on an 18-yard pitchout,[150] and Yale won, 35–28, in Boston on November 18. Larry Brown, Harvard's senior quarterback, set a Harvard standard for touchdown passes in The Game. Neil Rose, Ryan Fitzpatrick, a future NFL starting quarterback, and Chris Pizzotti would each toss four touchdowns versus Yale in 2001, 2003, and 2007, respectively, matching Brown.[151]

Brown would teach a seminar at Harvard on the multiflex the next academic semester.[152][153]

The most memorable pass of the afternoon was tossed by a future participant in the NFL. Tight end John Spagnola, a future eleven year NFL veteran and participant in Super Bowl XV, lofted a spiral to fellow receiver Bob Krystyniak for a touchdown to conclude a trick play. The extra point provided the 21-point cushion Brown almost wore out with two more touchdown passes.[154]

Carm Cozza fielded questions on the 1968 contest for a portion of his post-game interview.[155]

1979

On November 17, Harvard upset, 22–7, an undefeated, untied, 13.5 point Las Vegas-favored Yale team in New Haven before an estimated crowd of 72,000. The Crimson was shocked by the outcome, publishing the following week a sports column under the headline "The Shock of 1979". Yale had clinched the League title the week before with a 35–10 victory over Princeton at Palmer Stadium.[156] Not even the Harvard Crimson sports editor, or a peer at any of the other seven League newspapers, predicted Harvard would win.[157]

Harvard running back Jim Callinan and the offense set the tone with an opening game drive of 74 yards, 64 by the run, on 17 plays. Callinan caught a 23-yard touchdown pass later in the afternoon. Harvard ran for 152 yards from scrimmage while Yale managed 92 yards. Yale fumbled six times but recovered three, unlike the 1968 Yale team that fumbled six times with Harvard recovering each fumble.[158][143]

Harvard lost its starting and backup quarterback before the season started. Injuries forced four other quarterbacks onto the field with hope each had mastered Joe Restic's complicated multiflex offense. Brian Buckley, Ron Cuccia, Mike Smerczynski, Joe Lahti, Mike Buchannan, and Burke St. John—who quarterbacked the 22 – 7 victory—were each listed at least once as the Crimson's starting quarterback during the season.[159] Harvard employed two tightends and an unbalanced offensive line to control the line scrimmage.

Harvard finished the season 3 – 6 and thwarted again a Yale team a win away from an unblemished football season. Yale would have celebrated its first undefeated, untied season since 1960 and its second in 56 years with a win.[160] Yale clinched sole possession of the League football title the week before at Princeton.

1983

The game played on November 19 marked the 100th time the programs met on the gridiron. Harvard won, 16–7, in New Haven. Captain, linebacker and later Bingham Award winner Joe Azelby led the Crimson. Harvard outrushed Yale 259 yards to 61. Yale endured its worst season of all time, finishing 1–9.[161]

Yale lead series 54–38–8 at the 100 game mark.

1987

On November 21, the weather conditions at the Bowl were somewhat similar to the 1967 NFL Championship Game in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Game time temperature approached the high teens and 40 mph wind chilled the "real feel" temperatures to sub-zero Fahrenheit throughout the day. Harvard won, 14–10, before an announced crowd of 66,548.

Joe Restic guided the Crimson 8–2 overall and 6–1 League records, both bests for Restic. Harvard won the League football title.

1993

On November 20, a gameball was presented to Theo Epstein, a Yale Daily News sports section editor. Epstein, later a noted sports executive, authored a column calling for Yale head coach Carm Cozza to retire, published the day before the 110th contest in the series. The column appeared to arouse the Bulldogs. Harvard, the program playing its last game under Joe Restic, appeared aroused, too. The 33–31 outcome is the all–time highest combined score in the series. Both teams had each won one game, and not versus Princeton, in the League entering the contest. The teams both finished with 3–7 overall records.

Twenty five years before, almost to date, Harvard achieved a climatic 29–29 win versus Yale. The New York Times sportswriter William N. Wallace wrote "Twenty-five years ago Harvard scored 26 points in the last 42 seconds at Cambridge to tie Yale, 29–29, in an epic battle between two undefeated teams."[162] (Wallace authored an authoritative book on an important game in the Princeton–Yale football rivalry, Yale's Ironmen: A Story of Football + Lives in the Decade of the Depression + Beyond.) Harvard mounted a fourth quarter comeback, and though it mauled the Yale return man and caused a melee on an onside kick after scoring on a 77-yard pass and a run play for the 2-point coconversion, the Crimson couldn't send off Restic with a victory.

1995

On November 18 in New Haven, Harvard, 1–6 in the League, defeated Yale, 22–21. Coach Murphy's charges would soon dominate the series. Murphy scored an astounding 17–6 versus four Yale counterparts, including Carm Cozza.

1999

On November 20, quarterback Eric Walland and receiver Eric Johnson set single game Yale records for passing yardage, passing attempts and completions, 437 yards on 42 completions from 67 attempts, and receiving yardage and receptions, 244 yards and 21 receptions.[163] Yale won the contest on a touchdown pass to Johnson from Walland with 0:29 remaining in the game.

Yale rallied late and in thrilling fashion to win the year before and the year after.[164]

2001

On November 17, Harvard defeated Yale, 35–23, in New Haven. The win sealed the Crimson's first perfect season since 1913. Percy Haughton had last lead Harvard to undefeated and untied seasons, 9–0, in 1912 and 1913. Yale's three-game win streak in the series ended. Neil Rose completed four touchdown passes.

2004

On November 20, the Harvard team, a team that eight times scored at least 30 points against an opponent during the season, completed the program's third undefeated season with a 35–3 victory versus Yale. Future NFL quarterback and Buffalo Bills captain Ryan Fitzpatrick, who captained the Harvard team, earned the season's Frederick Greeley Crocker award as team MVP and the Asa Bushnell Cup as League Player of the Year. Fifteen Harvard athletes were named to the All-Ivy squad.[165] The undefeated season was Tim Murphy's second in four seasons.

Yale undergraduate pranksters, led by Michael Kai and David Aulicino, won handily, too. The 2004 Harvard–Yale prank gained national press coverage through the early part of the week following the contest. Jimmy Kimmel Live!, among other news, sports and entertainment media, gave notice that Harvard fans raised cards in unison that read WE SUCK. Yale fans applauded appreciatively in acknowledgement from the other side of Soldiers Field.[166]

2005

Clifton Dawson's 258th carry for the season, a record, delivered to Harvard the triple-overtime victory, 30–24, on November 19 in New Haven. The contest was the longest ever at the Bowl and in Ivy League football history. Yale led, 21–3, in the third quarter.

Dawson is the Crimsom leader in career rushing attempts (958), career rushing yards (4,241), single-season rushing yards (1,302), career rushing touchdowns (60), and single-season rushing touchdowns (20).[167]

2009

On November 21, Harvard won 14–10. The contest concluded horribly for Yale head coach Tom Williams.

Yale nursed a 10–0 halftime lead to a 10–7 lead late in the fourth quarter. Then Williams, on fourth down and 22 yards to go for a first down from the Yale 26, chose to fake a punt. The attempt netted fifteen yards.

Harvard was behind 10–0 late in the fourth quarter. Harvard scored its first touchdown covering 76 yards in six plays. When Yale's fake punt failed Collier Winter soon passed to Chris Lorditch for the winning touchdown. Moments later Harvard linebacker Jon Takamura intercepted a pass to end the game.[168] Williams was soon released from his contract for presenting misleading information about being a candidate for a Rhodes Scholarship.[169]

The Yale Freshmen Council loss the battle versus university administration over design of a T-shirt, approved by class-wide vote, that quoted F. Scott Fitzgerald. The T-shirt was banned that quoted the sentiment voiced by Amory Blaine from This Side of Paradise that "Harvard men are sissies".

2014

Conner Hempel completed a 35-yard touchdown pass to Andrew Fischer with 0:55 remaining in the contest and Harvard defeated Yale 31–24. Harvard won outright the League football title on November 22. A Yale victory would have created a three-way tie for the League football title among Dartmouth, Harvard and Yale. Harvard led 24–7 at the end of the third quarter. Harvard finished season ranked in several Top 20 college football polls for its NCAA division.

The Emmy-winning ESPN College GameDay was broadcast from Boston. Lee Corso predicted Yale would win on the premiere college football television show. A little more than a week before the contest, Yale students protested the cost of the football program, particularly given the recent poor record.

Tyler Varga gained 127 yards on 30 carries and scored two touchdowns for Yale but Harvard completed the season undefeated and untied, the third time during Tim Murphy's tenure.

Deon Randall for Yale and Norm Hayes for Harvard captained the teams, the first time African American athletes represented each rival at the opening coin toss. Both were voted First team All-Ivy football, Randall at receiver (for the second straight year) and Hayes at defensive back. Tim Murphy was voted Coach of the Year.

2015

The football game held November 21 was the first that ended after sunset at the Bowl, and was won by Harvard, 38–19. The 2:30 kickoff forced play after dusk. Harvard extended to nine games its winning streak versus Yale, the longest winning streak in the series. Harvard shared the League title, the third straight season it shared or won outright the title, another school record.

Justice Shelton-Mosley gained 119 yards, scoring two touchdowns, on five receptions, and scored on an eight-yard run from scrimmage. The first touchdown reception covered fifty-three yards, the second covered thirty-five yards. The fourth quarter eight-yard touchdown run ended his day. Shelton-Mosley was named Ivy League Rookie of the Year.[170]

2016

The game played November 19 in Boston ended two streaks. Yale won, 21–14, denying Harvard its fourth consecutive shared or outright Ivy League football title, and ending Yale's nine-game losing streak in The Game.

2019

Like many previous iterations of The Game, the regular season finale between Yale and Harvard had Ivy League Championship implications. Yale and Dartmouth began the day tied for the Ivy League lead, at 5–1 in conference play. Yale was ranked 25th in the national FCS coaches poll entering the game after defeating 19 ranked Princeton a week before. The first half of the 136th edition of The Game surprised odds makers with a 15-3 Harvard lead.

Halftime began at 1:40 PM, but the start of the third quarter was delayed when a small group of protesters staged a sit-in at midfield and were soon joined by more than 500 spectators,[171] including students and alumni from Harvard and Yale. Among the causes being protested, the media coverage focused most on the calls for the two universities to divest from fossil fuel holdings[172] and Puerto Rican debt.[173] Play resumed a just over an hour later after security escorted out the 42 individuals who refused to leave.[174]

For most of the second half, the Crimson had a commanding lead over the Bulldogs, including 19- and 17-point leads in the fourth quarter. With 90 seconds left in the game, a successful onside kick aided Yale in scoring two touchdowns to force overtime. Both teams scored touchdowns on their first overtime possessions. The Bulldogs started with the ball in the second overtime and quickly scored a touchdown. On the ensuing Harvard possession the Bulldogs forced the Crimson to go four and out, ending the two-overtime struggle. The 50–43 score handed Yale a share of the Ivy League Championship, their second title in three years. The conclusion of the contest was threatened by the early sunset and the lack of lights in the 105-year-old stadium. The second half began at 2:48 PM, the sunset occurred at 4:26 PM, and the deciding Yale stop took place at 4:38 PM.[175] The thriller game itself, along with its importance in the Ivy League standings as well as the unexpected sit-in, led observers to immediately declare it a classic, with The New Haven Register, a popular local newspaper, stating that the game, "instantly took on legendary status in the annals of one of college football’s most prestigious rivalries."[176] Notably, Harvard running back Aidan Borguet delivered one of the most statistically outstanding and anomalous performances in the history of college football in the loss, finishing the contest with 269 rushing yards and 4 touchdowns on 11 carries for an average of 24.5 yards/carry.[177]

Record

The football teams of Harvard and Yale have been meeting nearly annually since their first game on November 13, 1875. Following is a table of dates, scores and venues of Harvard–Yale games.[178][179] All games were played on Saturdays except those in 1883 and 1887 when the game was played on Thursday, Thanksgiving Day. Since 1945 the game has been played in New Haven, Connecticut in odd years and in Boston, Massachusetts in even years. As of November 2019, 136 games have been played. Yale has 69 wins and Harvard has 60 wins (8 games ended as ties). Harvard has the longest winning streak (nine games).

Results

Harvard victories are shown in ██ crimson, Yale victories in ██ blue, and tie games in ██ light gray. The - symbol denotes a skipped year.

| Game | Date | Winning Team | Score | Venue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | November 13, 1875 | Harvard | 4g,2t–0 | Hamilton Park, New Haven | Until 1883, goals from a kick ("g") and touchdowns ("t") were tracked separately, and in 1875 and 1876, touchdowns did not count for a score.[180] |

| 2 | November 18, 1876 | Yale | 1g–2t | Hamilton Park, New Haven | [180] |

| — | |||||

| 3 | November 23, 1878 | Yale | 1g–0 | South End Grounds, Boston | Between 1877 and 1882, a touchdown counted for 1/4 of a goal.[180] |

| 4 | November 8, 1879 | Tie | 0–0 | Hamilton Park, New Haven | |

| 5 | November 20, 1880 | Yale | 1g,1t–0 | South End Grounds, Boston | Between 1877 and 1882, a touchdown counted for 1/4 of a goal.[180] |

| 6 | November 12, 1881 | Yale | 0–4s | Hamilton Park, New Haven | Yale was awarded victory on safeties, as, in a tie, the team having 4 or more safeties than the other would lose.[180] |

| 7 | November 25, 1882 | Yale | 1g,3t-0 | Holmes Field, Cambridge | Between 1877 and 1882, a touchdown counted for 1/4 of a goal.[180] |

| 8 | November 29, 1883 | Yale | 23–2 | Polo Grounds, New York | Match was played on Thursday, Thanksgiving Day |

| 9 | November 22, 1884 | Yale | 52–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| — | Harvard banned football in 1885[181] | ||||

| 10 | November 20, 1886 | Yale | 29–4 | Jarvis Field, Cambridge | |

| 11 | November 24, 1887 | Yale | 17–8 | Polo Grounds, New York | Match was played on Thursday, Thanksgiving Day |

| — | |||||

| 12 | November 23, 1889 | Yale | 6–0 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | |

| 13 | November 22, 1890 | Harvard | 12–6 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | |

| 14 | November 21, 1891 | Yale | 10–0 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | |

| 15 | November 19, 1892 | Yale | 6–0 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | Harvard introduced flying wedge formation |

| 16 | November 25, 1893 | Yale | 6–0 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | New York Times game preview and lineups[182] |

| 17 | November 24, 1894 | Yale | 12–4 | Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts | |

| — | The 1894 game was so violent that the series was suspended for two years[183] | ||||

| — | |||||

| 18 | November 13, 1897 | Tie | 0–0 | Soldiers Field, Cambridge | |

| 19 | November 19, 1898 | Harvard | 17–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 20 | November 18, 1899 | Tie | 0–0 | Soldiers Field, Cambridge | |

| 21 | November 24, 1900 | Yale | 28–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 22 | November 23, 1901 | Harvard | 22–0 | Soldiers Field, Cambridge | |

| 23 | November 22, 1902 | Yale | 23–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | Crowd of 30,000 saw contest. |

| 24 | November 21, 1903 | Yale | 16–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 25 | November 19, 1904 | Yale | 12–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 26 | November 25, 1905 | Yale | 6–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 27 | November 24, 1906 | Yale | 6–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 28 | November 23, 1907 | Yale | 12–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 29 | November 21, 1908 | Harvard | 4–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | HOF Harvard Coach Percy Haughton allegedly strangled a live bulldog and threw its dead carcass at players in the locker room before the game to motivate his players to victory.[184] However, according to research published by the Los Angeles Times in 2011, it is likely that this story is a myth. According to the research, it is much more probable that the coach strangled a fake bulldog made of papier-mâché. |

| 30 | November 20, 1909 | Yale | 8–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 31 | November 19, 1910 | Tie | 0–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 32 | November 25, 1911 | Tie | 0–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 33 | November 23, 1912 | Harvard | 20–0 | Yale Field, New Haven | |

| 34 | November 22, 1913 | Harvard | 15–5 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Electrical World article on The Game[185] |

| 35 | November 21, 1914 | Harvard | 15–5 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Image of The Game [186] |

| 36 | November 20, 1915 | Harvard | 41–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 37 | November 25, 1916 | Yale | 3–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| — | Both Harvard and Yale suspended their football programs during World War I. | ||||

| — | Both Harvard and Yale suspended their football programs during World War I. | ||||

| 38 | November 22, 1919 | Harvard | 10–3 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 39 | November 20, 1920 | Harvard | 9–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | 80,000 fans attended[187] |

| 40 | November 19, 1921 | Harvard | 10–3 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 41 | November 25, 1922 | Harvard | 10–3 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 42 | November 24, 1923 | Yale | 13–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 43 | November 22, 1924 | Yale | 19–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 44 | November 21, 1925 | Tie | 0–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 45 | November 20, 1926 | Yale | 12–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 46 | November 19, 1927 | Yale | 14–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 47 | November 24, 1928 | Harvard | 17–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 48 | November 23, 1929 | Harvard | 10–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 49 | November 22, 1930 | Harvard | 13–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 50 | November 21, 1931 | Yale | 3–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 51 | November 19, 1932 | Yale | 19–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Time Magazine article on The Game[188] |

| 52 | November 25, 1933 | Harvard | 19–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 53 | November 24, 1934 | Yale | 14–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 54 | November 23, 1935 | Yale | 14–7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | In 1935 Gerald Ford was an assistant coach for Yale[189] |

| 55 | November 21, 1936 | Yale | 14–13 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Game featured 1936 Heisman winner Larry Kelley[190] |

| 56 | November 20, 1937 | Harvard | 13–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Game featured 1937 Heisman winner Clint Frank[191] |

| 57 | November 19, 1938 | Harvard | 7–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 58 | November 25, 1939 | Yale | 20–7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 59 | November 23, 1940 | Harvard | 28–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 60 | November 22, 1941 | Harvard | 14–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 61 | November 21, 1942 | Yale | 7–3 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| — | While Yale continued its football program during World War II, Harvard suspended theirs and played no games in 1943 and 1944. | ||||

| — | While Yale continued its football program during World War II, Harvard suspended theirs and played no games in 1943 and 1944. | ||||

| 62 | December 1, 1945 | Yale | 28–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Harvard did not restart its football program until shortly after VJ-Day, after Yale had already closed its 1945 schedule. It was agreed that Yale would add Harvard at the end of its schedule on December 1 (the only time the two teams played a December game) - with the location being at the Yale Bowl - reversing the tradition in place since 1897 that games in odd years would be played at Harvard's field, while games in even years would be played at Yale. Since the 1945 game, games in odd years would be played at the Yale Bowl and games in even years would be played at Harvard Stadium. |

| 63 | November 23, 1946 | Yale | 27–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 64 | November 22, 1947 | Yale | 31–21 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 65 | November 20, 1948 | Harvard | 20–7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 66 | November 19, 1949 | Yale | 29–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Game featured Yale captain Levi Jackson |

| 67 | November 25, 1950 | Yale | 14–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 68 | November 24, 1951 | Tie | 21–21 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 69 | November 22, 1952 | Yale | 41–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 70 | November 21, 1953 | Harvard | 13–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 71 | November 20, 1954 | Harvard | 13–9 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 72 | November 19, 1955 | Yale | 21–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | End Ted Kennedy scored Harvard's only touchdown.[192] Down 14–0 in the third quarter, he caught an eight-yard pass from Walt Stahura to complete a 79-yard drive.[193][194][195] Earlier in the game, Kennedy had been unable to hold onto a fourth-down pass in the end zone.[195] |

| 73 | November 24, 1956 | Yale | 42–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 74 | November 23, 1957 | Yale | 54–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 75 | November 22, 1958 | Harvard | 28–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 76 | November 21, 1959 | Harvard | 35–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 77 | November 19, 1960 | Yale | 39–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 78 | November 25, 1961 | Harvard | 27–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 79 | November 24, 1962 | Harvard | 14–6 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 80 | November 30, 1963 | Yale | 20–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Tim Merrill, native of Cambridge, Ohio intercepted a pass that made it possible for Yale's go-ahead score. Game delayed a week after the death of President John F. Kennedy, Harvard 1940. |

| 81 | November 21, 1964 | Harvard | 18–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 82 | November 20, 1965 | Harvard | 13–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 83 | November 19, 1966 | Harvard | 17–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 84 | November 25, 1967 | Yale | 24–20 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 85 | November 23, 1968 | Tie | 29–29 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | The Harvard Student Newspaper printed the title Harvard Beats Yale 29-29, which became the title of a famous 2008 documentary film. This was the final tie in the rivalry, as modern college football rules do not allow tie games.[196][141] |

| 86 | November 22, 1969 | Yale | 7–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 87 | November 21, 1970 | Harvard | 14–12 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 88 | November 20, 1971 | Harvard | 35–16 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 89 | November 25, 1972 | Yale | 28–17 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 90 | November 24, 1973 | Yale | 35–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 91 | November 23, 1974 | Harvard | 21–16 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 92 | November 22, 1975 | Harvard | 10–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 93 | November 13, 1976 | Yale | 21–7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 94 | November 12, 1977 | Yale | 24–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 95 | November 18, 1978 | Yale | 35–28 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 96 | November 17, 1979 | Harvard | 22–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 97 | November 22, 1980 | Yale | 14–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 98 | November 21, 1981 | Yale | 28–0 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 99 | November 20, 1982 | Harvard | 45-7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Harvard and Yale moved to NCAA Division I-AA; MIT pulled the famous weather balloon prank. |

| 100 | November 19, 1983 | Harvard | 16–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 101 | November 17, 1984 | Yale | 30–27 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 102 | November 23, 1985 | Yale | 17–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 103 | November 22, 1986 | Harvard | 24–17 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 104 | November 21, 1987 | Harvard | 14–10 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 105 | November 19, 1988 | Yale | 26–17 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 106 | November 18, 1989 | Harvard | 37–20 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 107 | November 17, 1990 | Yale | 34–19 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | MIT fired a rocket with an MIT banner over the goal post. |

| 108 | November 23, 1991 | Yale | 23–13 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 109 | November 21, 1992 | Harvard | 14–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 110 | November 20, 1993 | Yale | 33–31 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 111 | November 19, 1994 | Yale | 32–13 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 112 | November 18, 1995 | Harvard | 22–21 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 113 | November 23, 1996 | Harvard | 26–21 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 114 | November 22, 1997 | Harvard | 17–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 115 | November 21, 1998 | Yale | 9–7 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 116 | November 20, 1999 | Yale | 24–21 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 117 | November 18, 2000 | Yale | 34–24 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 118 | November 17, 2001 | Harvard | 35–23 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 119 | November 23, 2002 | Harvard | 20–13 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Images from The Game[197] |

| 120 | November 22, 2003 | Harvard | 37–19 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | 53,136 fans attended.[198] |

| 121 | November 20, 2004 | Harvard | 35–3 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Recap.[199] Yale pulled a high-profile prank. |

| 122 | November 19, 2005 | Harvard | 30–24 (3OT) | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 123 | November 18, 2006 | Yale | 34–13 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 124 | November 17, 2007 | Harvard | 37–6 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 125 | November 22, 2008 | Harvard | 10–0 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 126 | November 21, 2009 | Harvard | 14–10 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Failed fake punt attempt by Yale on fourth-and-22 at their own 25-yard-line in the closing minutes likely cost the Bulldogs the game.[200] |

| 127 | November 20, 2010 | Harvard | 28–21 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 128 | November 19, 2011 | Harvard | 45–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Tragic fatal U-Haul crash during tailgate.[201]

Same score as Harvard record-setting 1982 game. |

| 129 | November 17, 2012 | Harvard | 34–24 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 130 | November 23, 2013 | Harvard | 34–7 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 131 | November 22, 2014 | Harvard | 31–24 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | Harvard hosted ESPN's College Gameday.[202] |

| 132 | November 21, 2015 | Harvard | 38–19 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 133 | November 19, 2016 | Yale | 21–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 134 | November 18, 2017 | Yale | 24–3 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 135 | November 17, 2018 | Harvard | 45–27 | Fenway Park (Harvard Home), Boston | |

| 136 | November 23, 2019 | Yale | 50–43 (2OT) | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Yale scored 14 points within the final 90 seconds of regulation to tie the game, then won in double overtime.[203]

Second half delayed by 45 minutes due to joint protest by Fossil Free Yale and Divest Harvard, demanding both universities divest from fossil fuels.[204][205] |

| November, 2020 | Scheduled for Harvard Stadium, Boston | Canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. | |||

| 137 | November 20, 2021 | Harvard | 34–31 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | |

| 138 | November 19, 2022 | Yale | 19–14 | Harvard Stadium, Boston | |

| 139 | November 18, 2023 | Yale | 23–18 | Yale Bowl, New Haven | Over 51,000 fans attended.[206] |

Past participants and teams

Some past participants and teams have been noteworthy. Yale claims twenty seven collegiate national football season-ending number one poll rankings or championships.[207][208] Harvard football claims seven such rankings or championships.[209]

Yale or Harvard athletes, cheerleaders, coaches, journalists, and student managers associated with The Game include: Howard M. Baldrige, George W. Bush, Jonathan Bush, Prescott Bush,[26] Ruly Carpenter, Frederick B. Dent, Richardson Dilworth, John T. Downey, Theo Epstein, Gerald Ford, Jack Ford, Pudge Heffelfinger, John Hersey, Charles B. Johnson, Dean Loucks, Archibald MacLeish, Michael McCaskey, Lee McClung, Vance McCormick, Stone Phillips, Philip W. Pillsbury, William Proxmire, Frederic Remington, Percy Avery Rockefeller, Kurt Schmoke, Bob Shoop, Steve Skrovan, Amos Alonzo Stagg, George Woodruff and William Wrigley III for Yale;[210] and Steve Ballmer, Wilder Dwight Bancroft, Edward Bowditch, Frank Champi, Henry Chauncey, Adam Clymer, John Culver, Arthur Cumnock, C. Douglas Dillon, Hamilton Fish III, Tim Fleiszer, Victor E. Gatto, Huntington Hardwick, Ray Hornblower, Dan Jiggetts, Tommy Lee Jones, Robert F. Kennedy, Ted Kennedy, Everett J. Lake, William Henry Lewis, Lucius Nathan Littauer, Torbert MacDonald, Kenneth O'Donnell, Chester Middlebrook Pierce, Henry Dwight Sedgwick, Thomas F. Stephenson, Jeffrey Ross Toobin, Walter H. Trumbull, Pete Varney and W. Barry Wood, Jr. for Harvard;[211]

- Fifteen Rhodes Scholarship recipients, eight representing Yale, seven representing Harvard;[212]

- Heisman Trophy winners Larry Kelley and Clint Frank (Frank won also the Maxwell Award), both for Yale, and Heisman finalists Endicott Peabody II, an offensive lineman for Harvard, and Brian Dowling and Rich Diana, offensive backfield players, for Yale;

- Fifty members of the College Football Hall of Fame, twenty-nine affiliated with Yale and twenty-one affiliated with Harvard, the most recent inductees Dick Jauron from Yale, Class of 2015, and Pat McInally from Harvard, Class of 2016;

- Seventeen holders of the Asa S. Bushnell Cup, the Player of the Year award for Ivy League football, nine representing Harvard, eight representing Yale;[213]

- Twenty-one designees to the Ivy League Silver Anniversary Team, sixteen from Yale and five from Harvard;[214]

- Twenty winners of the Gridiron Club of Greater Boston's George H. "Bulger" Lowe Award, honoring New England's best collegiate football athlete, twelve from Harvard, eight from Yale – and eleven winners of the Nils V. "Swede" Nelson Award for "academics, athletics, sportsmanship and citizenship," seven from Yale, four from Harvard;[147][215]

- Super Bowl participants Matt Birk, Rich Diana, John Dockery, Gary Fencik, Pat Graham, Calvin Hill, Kenny Hill, Isaiah Kacyvenski, Pat McInally, Chuck Mercein, and John Spagnola;

- Ninety Harvard football athletes are members of the Harvard Varsity Hall of Fame and twenty-seven Yale football athletes have won the William Mallory Award;[216][217]

- Thirty-two teams, seventeen representing Harvard and fifteen representing Yale, have won outright or shared the Ivy League football title;

- Nearly 300 football All Americans are affiliated with the programs;

- Five Yale teams won enough support for inclusion on the season's final AP or UPI CollegeFootball Poll: 12th in 1936, 12th in 1937, 12th in 1946, and 14th in 1960 AP polls, with 17th- and 18th-place rankings, respectively, on the 1956 and 1960 UPI polls.[218]

Noteworthy pranks

1933

Prior to The Game Handsome Dan II, Yale's bulldog mascot, was kidnapped (allegedly by members of the Harvard Lampoon); then, the morning after a 19–6 upset by Harvard over Yale, after hamburger was smeared on the feet of the statue of John Harvard that sits in front of University Hall in Harvard Yard, an image was captured of Handsome Dan licking John Harvard's feet. The photo ran on the front page of papers throughout the country.[219]

1955

Three greased pigs diverted the attention of 56,000 spectators at halftime on a snowy Saturday in New Haven. The pigs eluded tackles by groundskeepers and "compiled the most yards rushing of the afternoon," reported Charles Steedman of The Harvard Crimson. Rumor had it the Harvard Lampoon was responsible for the exhibition of porcine football skill on the gridiron. The Crimson reported "in any event it was certain [the pigs] hadn't been playmates of Handsome Dan."[220]

1961

In 1961, The Harvard Crimson handed out a parody of The Yale Daily News indicating that President John F. Kennedy ‘40 would be at the game in New Haven. At The Game, Robert Ellis Smith ‘62, the President of The Crimson, wore a mask of President Kennedy and walked onto the field, flanked by “Secret Service” agents and a Harvard friend dressed as a military aide, as the Harvard Band played “Hail to the Chief.” Reportedly, thousands of spectators were fooled."[221]

1969

Two staffers of the Harvard College paper published and distributed a mock copy of The Yale Daily News, datelined November 22, 1969. Readers were greeted with headlines "Disease Strikes 16 Eli Football Starters; Bulldogs Forced to Forfeit Harvard Game" and "Last Year's Stars Want to Fill in". Female cheerleaders were the alleged source of an STD rampaging through the football roster. Yale was in its first semester of coeducation.[222]

1983