ʿApiru (Ugaritic: 𐎓𐎔𐎗𐎎, romanized: ʿPRM, Ancient Egyptian: 𓂝𓊪𓂋𓅱𓀀𓏥, romanized: ʿprw), also known in the Akkadian version Ḫabiru (sometimes written Habiru, Ḫapiru or Hapiru; Akkadian: 𒄩𒁉𒊒, ḫa-bi-ru or *ʿaperu) is a term used in 2nd-millennium BCE texts throughout the Fertile Crescent for a social status of people who were variously described as rebels, outlaws, raiders, mercenaries, bowmen, servants, slaves, and laborers.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Etymology

| ꜥpr.w[7] in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The term was first discovered in its Akkadian version "ḫa-bi-ru" or "ḫa-pi-ru". Due to later findings in Ugaritic and Egyptian which used the consonants ʿ, p and r, and in light of the well-established sound change from Northwest Semitic ʿ to Akkadian ḫ,[8] the root of this term is proven to be ʿ-p-r.[9][10][6][11][12] This root means "dust, dirt", and links to the characterization of the ʿApiru as nomads, mercenaries, people who are not part of the cultural society.[6][11] The morphological pattern of the word is qatilu,[10] which point to a status, condition.[6]

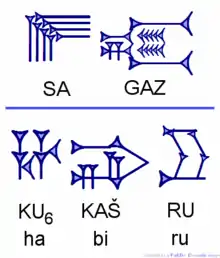

The Sumerogram SA.GAZ

The Akkadian term Ḫabiru occasionally alternates with the sumerograms SA.GAZ. Akkadian dictionaries for sumerograms added to SA.GAZ the gloss "ḫabatu" (raider), which raised the suggestion to read the sumerograms as this word. However, the Amarna letters attested the spelling SA.GA.AZ, and letters from Ugarit attested the spelling SAG.GAZ, which points that these sumerograms were read as written, and did not function as ideograms. The only Akkadian word which fits such spelling is "šagašu" (murderer or barbarian), but an Akkadian gloss to an Akkadian word seems odd, and the meaning of "šagašu" doesn't fit the essence of the Ḫabiru. Therefore, the meaning of SA.GAZ should probably be found in West Semitic word such Aramaic ŠGŠ which means muddy, restless,while the word "ḫabatu" should be interpreted as "nomad", and that fits the meaning of the word Ḫabiru/ʿApiru.[13]

Hapiru, Habiru, and Apiru

In the time of Rim-Sin I (1822 BCE to 1763 BCE), the Sumerians knew a group of Aramaean nomads living in southern Mesopotamia as SA.GAZ, which meant "trespassers".[14] The later Akkadians inherited the term, which was rendered as the calque Habiru, properly ʿApiru. The term occurs in hundreds of 2nd millennium BCE documents covering a 600-year period from the 18th to the 12th centuries BCE and found at sites ranging from Egypt, Canaan and Syria, to Nuzi (near Kirkuk in northern Iraq) and Anatolia (Turkey).[15][16]

Not all Habiru were murderers and robbers:[17] in the 18th century BCE a north Syrian king named Irkabtum (c. 1740 BCE) "made peace with [the warlord] Shemuba and his Habiru,"[18] while the ʿApiru, Idrimi of Alalakh, was the son of a deposed king, and formed a band of ʿApiru to make himself king of Alalakh.[19] What Idrimi shared with the other ʿApiru was membership of an inferior social class of outlaws, mercenaries, and slaves leading a marginal and sometimes lawless existence on the fringes of settled society.[20] ʿApiru had no common ethnic affiliations and no common language, their personal names being most frequently West Semitic, but also East Semitic, Hurrian or Indo-European.[20][21]

| The spelling of singular ꜥApiru in

"The Conquest of Joppa" tale[22] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In the Amarna letters from the 14th century BCE, the petty kings of Canaan describe them sometimes as outlaws, sometimes as mercenaries, sometimes as day-labourers and servants.[3] Usually they are socially marginal, but Rib-Hadda of Byblos calls Abdi-Ashirta of Amurru (modern Lebanon) and his son ʿApiru, with the implication that they have rebelled against their common overlord, the Pharaoh.[3] In "The Conquest of Joppa" (modern Jaffa), an Egyptian work of historical fiction from around 1440 BCE, they appear as brigands, and General Djehuty asks at one point that his horses be taken inside the city lest they be stolen by a passing ʿApir.[23]

Habiru and the biblical Hebrews

Except for its first appearance (Gen. 14:13), the biblical word "Hebrew", can be interpreted as a social category.[24] Since the discovery of the 2nd millennium BCE inscriptions mentioning the Habiru, there have been many theories linking these to the Hebrews of the Bible;[14] Most of which were based on the supposed etymological link and were widely denied following the Ugaritic and Egyptian discoveries.[6][11][12]

As pointed out by Moore and Kelle, while the ʿApiru/Ḫabiru may be related to the biblical Hebrews, they also appear to be composed of many different peoples, including nomadic Shasu and Shutu, the biblical Midianites, Kenites, and Amalekites, as well as displaced peasants and pastoralists.[25][26]

Scholars such as Anson Rainey have noted, however, that while ʿApiru covered the regions from Nuzi to Anatolia as well as Northern Syria, Canaan and Egypt, they were distinguished from Shutu (Sutu) or Shasu (Shosu), Syrian pastoral nomads in the Amarna letters or other texts of the time.[27] The morphological pattern of the word ʿApiru is, as mentioned above, qatilu, which point a status, as oppose to the morphological pattern of the term עִבְרִי (Hebrew) which is based on nisba (like מִצְרִי – Egyptian).[6] The ʿApiru were ethnically diverse, and hence this term is completely disconected from the term "Hebrew", in both etymology and meaning.[28] Professor Albert D. Friedberg concurs, arguing that Habiru refers to a social class found in every ancient Near Eastern society. [29]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Rainey 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Coote 2000, p. 549.

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Finkelstein & Silberman 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Noll 2001, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cochavi-Rainey, Zipora (2005). To the King my Lord (in Hebrew). Mosad Bialik. p. 12.

- ↑ Other versions:

![D36 [a] a](../I/hiero_D36.png.webp)

![Q3 [p] p](../I/hiero_Q3.png.webp)

![D21 [r] r](../I/hiero_D21.png.webp)

See: Ernest Alfred Wallis, An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary, John Murray, 1920, p. 119![D36 [a] a](../I/hiero_D36.png.webp)

![Q3 [p] p](../I/hiero_Q3.png.webp)

![Z7 [W] W](../I/hiero_Z7.png.webp)

![Z4 [y] y](../I/hiero_Z4.png.webp)

![D21 [r] r](../I/hiero_D21.png.webp)

- ↑ Cf. Pentiuc, Eugen J. (2001). West Semitic Vocabulary in the Akkadian Texts from Emar. Eisenbrauns. pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Pardee, Dennis (2004). "Textes akkadiens d'Ugarit (à propos du livre de Sylvie Lackenbacher)". Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire. 81 (1): 251–252. doi:10.3406/syria.2004.7787.

- 1 2 גרינברג, משה (1955). "לחקר בעית הח'ברו (ח'פרו) ("On the ḫabiru (ḫapiru) Problem")". Tarbiz. 24 (4): 376. ISSN 0334-3650.

- 1 2 3 Horon, A. G. (2000). East and West (in Hebrew). Dvir. p. 159.

- 1 2 רטוש, יונתן (1971). ""עבר" במקרא או ארץ העברים ("Eber" in the Bible or the Land of the Hebrews)". Beit Mikra. 16 (4 (47)): 568. ISSN 0005-979X.

- ↑ גרינברג, משה (1955). "לחקר בעית הח'ברו (ח'פרו) ("On the ḫabiru (ḫapiru) Problem")". Tarbiz. 24 (4): 375–376. ISSN 0334-3650.

- 1 2 Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 89.

- ↑ Rainey 2008, p. 52.

- ↑ Rainey 1995, pp. 482–483.

- ↑ Youngblood 2005, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Hamblin 2006, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Na'aman 2005, p. 112.

- 1 2 Redmount 2001, p. 98.

- ↑ Coote 2000, pp. 549–550.

- ↑ Gruen, Stephan W. (1972). "The Meaning of [unknown] in Papyrus Harris 500, Verso (= Joppa) 1, 5". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 58: 307. doi:10.2307/3856266. ISSN 0307-5133.

- ↑ Manassa 2013, pp. 5, 75, 107.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Moore & Kelle 2011, p. 125.

- ↑ Rainey 1995, p. 483.

- ↑ Rainey 1995, p. 490.

- ↑ גרינברג, משה (1955). "לחקר בעית הח'ברו (ח'פרו) ("On the ḫabiru (ḫapiru) Problem")". Tarbiz. 24 (4): 377. ISSN 0334-3650.

- ↑ D. Friedberg, Albert (22 February 2017). "Who Were the Hebrews?". The Torah.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023.

Bibliography

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864505.

- Collins, John J. (2014). A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451484359.

- Coote, Robert B. (2000). "Hapiru, Apiru". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2007). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743243636.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. ISBN 9781134520626.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2010). The A to Z of Ancient Israel. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461671725.

- Manassa, Colleen (2013). Imagining the Past: Historical Fiction in New Kingdom Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199982226.

- McKenzie, John L. (1995). The Dictionary Of The Bible. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684819136.

- McLaughlin, John L. (2012). The Ancient Near East. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426765506.

- Moore, Megan B.; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Grand Rapids, Michigan; Cambridge, UK. ISBN 9780802862600.

- Na'aman, Nadav (2005). Canaan in the Second Millennium B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061139.

- Noll, K.L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841273181.

- Rainey, Anson F. (2008). "Who Were the Early Israelites?" (PDF). Biblical Archaeology Review. 34:06 (Nov/Dec 2008): 51–55.

- Rainey, Anson F. (1995). "Unruly Elements in Late Bronze Canaanite Society". In Wright, David Pearson; Freedman, David Noel; Hurvitz, Avi (eds.). Pomegranates and Golden Bells. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464874.

- Redmount, Carol A. (2001). "Bitter Lives". In Michael David, Coogan (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139372.

- Van der Steen, Eveline J. (2004). Tribes and Territories in Transition. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042913851.

- Youngblood, Ronald (2005). "The Amarna Letters and the "Habiru"". In Carnagey, Glenn A.; Schoville, Keith N. (eds.). Beyond the Jordan: Studies in Honor of W. Harold Mare. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781597520690.