HMS Owen Glendower in Copenhagen in 1822, painted by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Owen Glendower |

| Namesake | Owain Glyndŵr[lower-alpha 1] |

| Ordered | 1 October 1806 |

| Laid down | January 1807 |

| Launched | 19 November 1808 |

| Fate | Sold in 1884 |

| General characteristics [6] | |

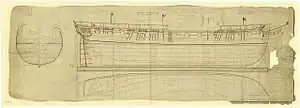

| Class and type | 36-gun fifth-rate Apollo-class frigate |

| Tons burthen | 9513⁄95 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 38 ft 3+1⁄2 in (11.671 m) |

| Depth of hold | 13 ft 3 in (4.04 m) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 285 |

| Armament |

|

HMS Owen Glendower (or Owen Glendour) was a Royal Navy 36-gun fifth-rate Apollo-class frigate launched in 1808 and disposed of in 1884. In between she was instrumental in the seizure of the Danish island of Anholt, captured prizes in the Channel during the Napoleonic Wars, sailed to the East Indies and South America, participated in the suppression of the slave trade, and served as a prison hulk in Gibraltar before she was sold in 1884.

Active duty

Captain William Selby, late of Cerberus, took command of Owen Glendower in January 1809.[6]

The Gunboat War

Early in May 1809, Vice-admiral Sir James Saumarez, the British commander-in-chief in the Baltic, sent a squadron, consisting of the 64-gun third rate Standard, Owen Glendower, three sloops (Avenger, Ranger, and Rose), and the gun-brig Snipe. The commander of the squadron was Captain Aiskew Paffard Hollis, captain of Standard. Their objective was to capture the Danish island of Anholt.[7] Anholt was small and essentially barren; its significance rested in the lighthouse that stood on its easternmost point. The Danes had extinguished it at the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and Denmark; the point of capturing the island was to restore the lighthouse to its function to assist British men-of-war and merchantmen in the Kattegat.[8]

The task force landed a party of seamen and marines, under the command of Selby, assisted by Captain Edward Nicolls of the Standard's Royal Marines. The Danes put up a short, ineffective resistance that killed one British marine and wounded two. Still, on 18 May the Danish garrison of 170 men surrendered, giving the British immediate possession of the island.[7]

The Channel

From late 1809 Owen Glendower operated in the Channel. On 10 March 1810, she came upon a French privateer lugger while her crew was boarding a schooner.[9] Selby chased the lugger for one and half hours. The lugger resisted until she was half full of water and had had two men killed and three wounded out of her crew of 58.[9] She turned out to be Camille, armed with only six of the fourteen guns she carried, having stored eight in her hold. She had sailed from Cherbourg only six hours earlier and had already captured the English schooner Fame, of London, William Proper, master, which had been sailing from Lisbon to London with a cargo of fruit. HMS Diana later recaptured Fame.[9]

On 26 March Owen Glendower sailed with a convoy for Quebec. On 27 September she sailed with a convoy for the Cape of Good Hope.[6]

Then on 1 October Owen Glendower, with Persian in company,[10] was escorting a convoy off The Lizard in thick fog. A master and crew from Roden,[10] one of the vessels in the convoy, came aboard and advised Selby that a French privateer cutter had taken his vessel. When the fog lifted, it turned out that the cutter was only a short distance away. The cutter did not surrender until a short cannonade wounded several of her crew. She turned out to be the 16 or 20-gun Indomptable, out of Roscoff, with a crew of 120 or 130 men.[11] She had formerly been the Revenue Cutter Swan, out of Cowes.[12] Selby also retook Roden.[10]

Selby died aboard Owen Glendower on 28 March 1811 whilst at the Cape of Good Hope .[13] Edward Henry A'Court, newly promoted to post-captain on 29 March, took temporary command of Owen Glendower.[6] He then sailed her back to Britain. Captain Bryan Hodgson transferred in July from HMS Barbadoes to replace A'Court as captain.[6]

East Indies

Owen Glendower's next cruise was to the East Indies. She was due to leave Portsmouth on 25 September 1811, but adverse winds detained her. She sailed five days later, only to be driven back to Falmouth. Finally, she sailed for India on 20 October. In 1812 she served as flagship for Vice Admiral Sir Samuel Hood in the East Indies.[6]

In May 1814 off the Nicobar Islands, Owen Glendower captured a U.S. privateer, the 12 or 16-gun vessel Hyder Ally, which had a crew of 30.[14][15] Hyder Ally was out of Portland, Maine and under the command of Captain Israel Thorndike. She carried sixteen cannons: twelve 18-pounder carronades, two 18-pounder guns, and two 9-pounder guns. Hyder Ally had already taken three prizes, which she had sent back to the US. (The British later retook all three. Earlier, Hyder Ally had escaped after being chased for three days by Salsette.[15]

Owen Glendower cruised the East Indies, stopping at such places as the Malacca Roads (21 August), Madras (29 August 1815), Penang and China, Trincomalee, and the like. She returned to England in the spring of 1816 and was laid up in May at Chatham.

Post-war

Between March 1817 and May 1819, Owen Glendower underwent major repairs at Chatham. She then was fitted for sea between June and October.[6]

South America

Captain the Honorable Robert Cavendish Spencer took command of Owen Glendower in August 1819.[6] He brought with him nearly all the officers and 18 young gentlemen from his previous command, Ganymede. Owen Glendower was nominally ready for sea, but Spencer found the reality less compelling. He therefore spent two and a half months re-rigging and re-fitting.[lower-alpha 2] He also discharged about a fifth of his crew and lost about the same proportion to sickness and desertion.[17]

Owen Glendower sailed for South America on 16 November. She arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 19 December after a record 33-day voyage that included a 24-hour stop in Funchal, Madeira. She then sailed for Montevideo and Buenos Aires where Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy was waiting to make her his flagship. She stayed in Buenos Aires for some time, but then sailed to St Helena on a fact-finding mission to report on the conditions under which Napoleon was living while in captivity. Contemporary accounts stress that Spencer's political affiliations were such that he would have been ready to find fault; instead, his report affirmed that Napoleon was well treated, though Napoleon chose not to grant Spencer an audience.[18] While Owen Glendower was away on this mission, Hardy transferred his flag to Creole.

Owen Glendower rounded Cape Horn despite bad weather and arrived in Valparaiso on 22 January 1821. Spencer was under orders to find Captain William Henry Shirreff of Andromache, who was a close friend of Lord Cochrane. (Cochrane was commander of the insurgent Chilean Navy in the fight for Chile's independence form Spain). Shirreff had ignored three previous recall messages and Spencer's orders were to arrest Shirreff if he continue to prove recalcitrant. The reason behind the recall was that Spain had complained that Shirreff had not maintained a strict neutrality.[19] Hardy, in Creole, joined Spencer at Valparaiso. Spencer found Andromache off Peru and Shirreff agreed, without a fuss, to return to Britain.[17]

Owen Glendower then spent three months off Spanish Peru, during which she visited the Galapagos Islands.[lower-alpha 3] One of her midshipmen was Robert FitzRoy, who, as captain of HMS Beagle, would take Charles Darwin there in 1834.[21] While Owen Glendower was at Callao, the Chilean fleet attacked the port. However, Cochrane's forces were not strong enough and he was forced to retire. During the attack, Spencer moved Owen Glendower to expose a Chilean vessel that had tried to take cover behind her.[17]

Blockade succeeded where force had not, and Spain entered into negotiations with the rebels. The negotiations took place on Owen Glendower. These negotiations continued after Spencer's recall and were completed on board Conway; the negotiations resulted in the formation of the Republic of Peru.[17]

Owen Glendower sailed for home with freight worth about £400,000.[lower-alpha 4] Off the Azores they encountered an American ship from Smyrna that had exhausted its food and water. Spencer provided some and told them that they were only a few hours away from Flores.[17] Owen Glendower arrived at Spithead on 19 January 1822.

The Eastern Atlantic

Owen Glendower underwent a refit that included rebuilding the stern that Sir Robert Sepping had given her. Spencer then sailed her, with his father, Earl Spencer, to Copenhagen to invest the Danish King with the Order of the Garter.[16] Two or three weeks later she was at Falmouth to determine its longitude. She then sailed to Madeira to determine Funchal's longitude. Owen Glendower then was paid off at Chatham.

Another midshipman on Owen Glendower at about this time who later came to be of note was Richard Brydges Beechey. He would go on to reach the rank of Rear Admiral. He was also a painter, and son and brother of painters.

Fighting the slave trade

In October 1821, the Admiralty appointed Captain Sir Robert Mends to the West Africa Squadron as Commodore and Senior Officer on the west coast of Africa, to be employed in the suppression of the slave trade. He commissioned Owen Glendower in November 1822.[6]

On 16 June 1823, Owen Glendower seized the Spanish slave schooner Concheta.[23]

Returning to Africa following an outbreak of yellow fever, Mends defended the Cape Coast against the threatened attack by the Ashanti. It was during this operation that he fell ill with cholera. He died three days later on 4 September.[6]

On 5 September the boats of the Owen Glendower seized the Spanish slave schooner Fabiana.[23]

Lieutenant Pringle Stokes temporarily took command of the ship.[24]

Hearing of the death of Sir Robert Mends, Commander John Filmore, who had recently arrived on the African Station, appointed himself to command the station and transferred to the Owen Glendower.[25]

On 8 February 1824 marines from Owen Glendower defended Cape Coast Castle following the Ashanti defeat of government forces: two marines and a Krooman were killed and two marines and five seamen from the ship wounded.[lower-alpha 5] Thereafter the vessel visited ports along the coast where the Ashanti might have been taking refuge. A letter dated 16 March 1824 from Major J. Chisholm, administrator of the colonial government and commander of the British troops on the Gold Coast, praised Owen Glendower and Captain Woolcombe for her role in suppressing unrest and possible insurrection at Elmina.[26] On 19 May 1824 Owen Glendower, under Captain Prickett, who also commanded the Naval Squadron, landed seamen and marines to occupy the forts on the coast while the army moved against the Ashanti.[27]

One of the officers on Owen Glendower during her time with the West Africa Squadron was Cheesman Henry Binstead. He served as an Admiralty Midshipman and later as an acting Lieutenant. He is most noted for the diaries that he kept, which detail life on the squadron. They record frustrations, slave ships chased and captured, fears of attack and imprisonment, impressions of the indigenous African people, and effects of ill-health and fever on the ship's men. When Owen Glendower finally returned to England, Binstead was one of the few of her original crew to have survived.

From October 1824 to February 1825, Owen Glendower was back at Chatham, undergoing refitting.[6] There Captain Hood Hanway Christian commissioned her for the Africa station,[6] where he would serve as Commodore.[28]

Cape of Good Hope

From early 1825 to early 1827, Owen Glendower was based at the Cape of Good Hope. On 10 March 1826, 19 sailors from Owen Glendower drowned in a boating accident at Simon's Bay when her pinnace swamped.[29] After another trip to England via St Helena, she was paid off at Chatham in July. Between December 1828 and December 1829, Owen Glendower was at Chatham, again undergoing repairs.[6]

Gibraltar

In March 1842 Owen Glendower was in Chatham, being fitted as a prison hulk to be based at Gibraltar.[6] > She then sailed from Chatham for Gibraltar in October with 200 convicts for work on the development of the Dockyard and the construction of a new breakwater there. Among the convicts were some who had run afoul of the restrictive political laws of the time, such as the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Once in Gibraltar, Owen Glendower then served for decades as a convict hulk.

Fate

In 1876 Gibraltar abolished the Convict Establishment and Owen Glendower, which had been operating as the convicts' hospital, became a receiving ship. In 1884 she was sold to F. Danino at Gibraltar,[30] for £1036.[6]

Notes

- ↑ Owain Glyndŵr (c. 1359 – c. 1416) was the last native Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales.[1][2][3] Owain Glyndŵr fought a long but unsuccessful campaign aimed at ending English rule in Wales.[4] The anglicisation of the name to Owen Glendower apparently comes from Holinshed's Chronicles, which served as one of Shakespeare's main sources for his history play Henry IV, Part One in which Glendower is a character. Glendower is referred to in Henry IV, Part Two, but he does not have a speaking role in that play. Owen Glendower was the only Royal Navy vessel to bear that name.[5]

- ↑ Spencer introduced "Congreve's Lights" at his own expense before the Board of Ordnance had authorized them.[16]

- ↑ While Spencer was in Peru a report reached London that he had been killed in a duel with his First Lieutenant; it was two months before the story was contradicted.[20]

- ↑ The Navy permitted captains returning to Britain to carry "freight" in the form of remittances. The captains earned a commission of one percent of the value, half of which they kept and half of which went to the Greenwich Hospital (London); unlike in the case of prizes, the crew did not share in the proceeds.[22]

- ↑ Also Krouman or Kruman. This was the term for an ex-slave, rescued from West Africa and locally recruited into the Royal Navy. The Navy used it as a title, such as "Krooman Jim Freeman", or "Head Krouman Jim Freeman".

Citations

- ↑ "Owain Glyndŵr". Glyndŵr University. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Owain Glyndwr". Dictionary of Welsh Biography.

- ↑ Mainwaring, Rachel (23 April 2016). "How Wales is marking 400 years since Shakespeare's death". Wales Online. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ Allday, D. Helen (1981). Insurrection in Wales: the rebellion of the Welsh led by Owen Glyn Dwr (Glendower) against the English Crown in 1400. Lavenham: Terence Dalton. p. 51. ISBN 0-86138-001-0.

- ↑ Colledge & Warlow (2006), p. 292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Winfield (2008), p. 167.

- 1 2 "No. 16260". The London Gazette. 23 May 1809. p. 736.

- ↑ James (1827) Vol. 5, 130.

- 1 2 3 "No. 16349". The London Gazette. 10 March 1810. p. 354.

- 1 2 3 "No. 16590". The London Gazette. 7 April 1812. p. 666.

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine (November 1810), Vol. 80 Part 2, p. 466.

- ↑ Lloyd's List,№4499.

- ↑ The gentleman's magazine, and historical chronicle, Volume 81, Part 1, p. 596.

- ↑ Niles's Weekly Register, 15 February 1815, 400.

- 1 2 "No. 16983". The London Gazette. 11 February 1815. p. 234.

- 1 2 The annual biography and obituary for the year 1832, Vol. 16, 5; London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Phillips, Michael – Owen Glendower

- ↑ Forsyth & Lowe (1853), p. 246.

- ↑ Vale (2001), p. 22.

- ↑ Le Marchant (1876), pp. 219–20.

- ↑ Gribbin and Gribbin (2003), pp. 24&30.

- ↑ Vale (2001), p. 23.

- 1 2 "No. 19845". The London Gazette. 10 April 1840. p. 953.

- ↑ British and Foreign State Papers (1825), p. 502.

- ↑ Marshall (1830), p. 434.

- ↑ "No. 18038". The London Gazette. 22 June 1824. pp. 1009–1011.

- ↑ "No. 18050". The London Gazette. 3 August 1824. pp. 1273–1274.

- ↑ "NMM, vessel ID 372643" (PDF). Warship Histories, vol iii. National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- ↑ Roth et al. (1906), p. 257.

- ↑ Colledge, p. 254.

References

- British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. 1825. p. 493. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Forsyth, William; Lowe, Hudson (1853). History of the captivity of Napoleon at St. Helena : from the letters and journals of the late Lieut.-Gen. Sir Hudson Lowe, and official documents not before made public. Vol. 3. Murray. OCLC 215830491.

- Gribbin, John R. and Mary Gribbin (2003) FitzRoy: the remarkable story of Darwin's captain and the invention of the weather forecast. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University). ISBN 978-0-300-10361-8

- James, William (1827) The naval history of Great Britain: from the declaration of war by France in 1793 to the accession of George IV. (London: R. Bentley).

- Le Marchant, Denis (1876). Memoir of John Charles Viscount Althorp, Third Earl Spencer. R. Bently. OCLC 665148904.

- Marshall, John (1831). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 3, part 1. London: Longman and company. p. 184.

- Michael Phillips, Ships of the Old Navy

- Michael Phillips, OWEN GLENDOWER (36) 1808

- Roth, Henry Ling, John Lister, J. Lawson Russel (1906) The Yorkshire coiners, 1767–1783: And notes on old and prehistoric Halifax (F. King & sons).

- Vale, Brian ( 2001) A frigate of King George: life and duty on a British man-of-war 1807–1829. (London: I.B. Tauris; New York: St. Martin's Press).

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

This article includes data released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported UK: England & Wales Licence, by the National Maritime Museum, as part of the Warship Histories project.