| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

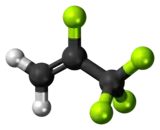

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoroprop-1-ene | |

| Other names

HFO-1234yf; R1234yf; R-1234yf; 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropylene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.104.879 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3161 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C3H2F4 | |

| Molar mass | 114 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless gas |

| Density | 1.1 g/cm3 at 25 °C (liquid); 4 (gas, relative, air is 1) |

| Boiling point | −30 °C (−22 °F; 243 K) |

| 198.2 mg/L at 24 °C, 92/69/EEC, A.6 | |

| log P | 2.15, n-octanol/water, 92/69/EEC, A.8 |

| Vapor pressure | 6,067 hPa at 21.1 °C; 14,203 hPa at 54.4 °C |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| H220, H280 | |

| P210, P260, P281, P308+P313, P410+P403 | |

| 405 °C (761 °F; 678 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 6.2% vol.; 12.3% vol. |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene, HFO-1234yf, is a hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) with the formula CH2=CFCF3. It is also designated R-1234yf as the first of a new class of refrigerants:[1] it is marketed under the name Opteon YF by Chemours and as Solstice YF by Honeywell.[2] R-1234yf is also a component of zeotropic refrigerant blend R-454B, an alternative to the R-410A refrigerant currently used in air conditioning and heat pump applications.

HFO-1234yf has a global warming potential (GWP) of less than 1,[3][4] compared to 1,430 for R-134a[5] and 1 for carbon dioxide. This colorless gas is being used as a replacement for R-134a as a refrigerant in automobile air conditioners. As of 2022, 90% of new U.S. vehicles from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are estimated to use HFO-1234yf.[6] One drawback is it breaks down into persistent organic pollutant short chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs).[7]

Adoption by automotive industry

HFO-1234yf was developed by a team at DuPont, led by Barbara Haviland Minor, which worked jointly with researchers at Honeywell.[8][9] Their goal was to meet European directive 2006/40/EC, which went into effect in 2011 and required that all new car platforms for sale in Europe use a refrigerant in its AC system with a global warming potential (GWP) below 150.[10][11]

HFO-1234yf was initially considered to have a 100-year GWP of 4, and is now considered to have a 100-year GWP lower than 1.[4][3] It can be used as a "near drop-in replacement" for R-134a,[12] the product previously used in automobile AC systems, which has a 100-year GWP of 1430.[5][13] This meant that automakers would not have to make significant modifications in assembly lines or in vehicle system designs to accommodate the product. HFO-1234yf had the lowest switching cost for automakers among the proposed alternatives.[14][15] The product can be handled in repair shops in the same way as R-134a, although it requires some different, specialized equipment to perform the service. One of the reasons for that is the flammability of HFO-1234yf.[16] Another issue affecting the compatibility between HFO-1234yf and R-134a-based systems is the choice of lubricating oil.[17]

Shortly after confirmation from automakers that HFO-1234yf would be adopted as a replacement of R-134a automotive air-conditioning refrigerant, in 2010, Honeywell and DuPont announced that they would jointly build a manufacturing facility in Changshu, Jiangsu Province, China to produce HFO-1234yf.[18] In 2017, Honeywell opened a new plant in Geismar, Louisiana, to produce the new refrigerant as well.[19][20] Although others claim to be able to make and sell HFO-1234yf, Honeywell and DuPont hold most or all of the patents issued for HFO-1234yf[18] and are considered the leading players in this area as of 2018.[21]

Flammability

Although the product is classified slightly flammable by ASHRAE, several years of testing by SAE International proved that the product could not be ignited under conditions normally experienced by a vehicle.[10] In addition, several independent authorities evaluated the safety of the product in vehicles and some of them concluded that it was as safe to use as R-134a, the product then in use in cars. In the atmosphere, HFO-1234yf degrades to trifluoroacetic acid,[22] which is a mildly phytotoxic[23] strong organic acid[24] with no known biodegradation mechanism in water. In case of fire it releases highly corrosive and toxic hydrogen fluoride and the highly toxic gas carbonyl fluoride.[25]

In July 2008, Honeywell and Du-Pont published a report claiming "HFO-1234yf is very difficult to ignite with electric spark", detailing the tests they did passing the gas over a hot plate heated to various temperatures in the range of 500–900 °C. Ignition was only seen when HFO-1234yf was mixed with PAG oil and passed over a plate that was >900 °C.[26]

In August 2012, Mercedes-Benz showed that the substance ignited when researchers sprayed it and A/C compressor oil onto a car's hot engine. A senior Daimler engineer who ran the tests, stated "We were frozen in shock, I am not going to deny it. We needed a day to comprehend what we had just seen." Combustion occurred in more than two-thirds of their simulated head-on collisions. The engineers also noticed etching on the windshield caused by the corrosive gases.[27] On September 25, 2012, Daimler issued a press release[10] and proposed a recall of cars using the refrigerant. The German automakers argued for development of carbon dioxide refrigerants, which they argued would be safer.[27]

In October 2012, SAE International established a new Cooperative Research Project, CRP1234-4, which included members of thirteen automotive companies, to extend its previous testing and investigate Daimler's claims.[10] A preliminary update as of December 2012[28] and a final report publicly released on July 24, 2013[10] agreed that R-1234yf was safe to use in automotive direct-expansion air conditioning systems. R-1234yf was believed not to increase the estimated risk of vehicle fire exposure. The report further stated that "the refrigerant release testing completed by Daimler was unrealistic" and "created extreme conditions that favored ignition".[10][29] The final report was supported by Chrysler/Fiat, Ford, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, PSA, Renault and Toyota. Daimler, BMW and Audi chose to withdraw from the SAE R-1234yf CRP Team.[10]

Following Mercedes' claims that the new refrigerant could be ignited, Germany's Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt (KBA, Federal Motor Transport Authority) conducted its own tests. They submitted a report to the European Union in August 2013. The Authority concluded that while R-1234yf was potentially more hazardous than previously used R-134a, it did not comprise a serious danger. Daimler disagreed with this conclusion and argued that the report supported their decision to continue to use older refrigerants.[30]

On July 23, 2010, General Motors announced that it would introduce HFO-1234yf in 2013 Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, and Cadillac models in the U.S.[31] Cadillac became the first American car to use R-1234yf in 2012.[32]

Since then, Chrysler,[33] GMC[34] and Ford[35] have all begun transitioning vehicles to R1234yf.[16] Japanese automakers are also making the transition to R1234yf. Honda and Subaru began to introduce the new refrigerant with the 2017 models.[32] From 2017 to 2018, BMW changed all of its models to R-1234yf. As of 2018, 50% of new vehicles from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are estimated to use R-1234yf.[36]

"The flammability issue has attracted a lot of attention, prompting the industry to conduct some serious third-party testing. The bottom line is this: The refrigerant will burn, but it takes a lot of heat to ignite it and it burns slowly. Almost every other fluid under the hood will light more easily and burn hotter than R1234yf, so the industry has determined that with proper A/C system design, it does not increase the chances of fire in the vehicle."[16]

Mixing HFO-1234yf with 10–11% R-134A is in development to produce a hybrid gas under review by ASHRAE for classification as A2L which is described as "virtually non-flammable". These gases are under review with the names of R451A and R451B. These mixes have GWP of ~147.[37]

Other additives have been proposed for lowering the flammability of HFO-1234yf, such as trifluoroiodomethane, which has a low GWP due to its short atmospheric lifetime, but is slightly mutagenic.[38]

Atmospheric transformation

HFO-1234yf has been shown to atmospherically transform into trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), leading to a potential for wet and dry atmospheric deposition.[39]

See also

- 1,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene (HFO-1234ze)

References

- ↑ Sciance, Fred (October 29, 2013). "The Transition from HFC- 134a to a Low -GWP Refrigerant in Mobile Air Conditioners HFO -1234yf" (PDF). General Motors Public Policy Center. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ "Honeywell and Chemours Announce New Manufacturing Plants for HFO 1234yf". Aspen Refrigerants. June 12, 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014 Full Report. World Meteorological Organization Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project—Report No. 55. 2014. p. 551.

- 1 2 "IPCC confirms HFO GWPs are less than 1". Cooling Post. 3 Feb 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 P. Forster; V. Ramaswamy; P. Artaxo; T. Berntsen; R. Betts; D.W. Fahey; J. Haywood; J. Lean; D.C. Lowe; G. Myhre; J. Nganga; R. Prinn; G. Raga; M. Schulz; R. Van Dorland (2007). "Chapter 2: Changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing". In Solomon, S.; Miller, H.L.; Tignor, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Marquis, M.; Chen, Z.; Manning, M.; Qin, D. (eds.). Climate Change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "StackPath". www.vehicleservicepros.com. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ↑ Wang, Ziyuan; Wang, Yuhang; Li, Jianfeng; Henne, Stephan; Zhang, Boya; Hu, Jianxin; Zhang, Jianbo (30 January 2018). "Impacts of the Degradation of 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene into Trifluoroacetic Acid from Its Application in Automobile Air Conditioners in China, the United States, and Europe". Environmental Science & Technology. 52 (5): 2819–2826. Bibcode:2018EnST...52.2819W. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b05960. PMID 29381347.

- ↑ "Recognizing excellence: Development of HFO-1234yf as the next generation refrigerant for the automotive industry" (PDF). 2010 DuPont Excellence Awards Sustainable Growth. 2010. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ↑ "DuPont Names Seven New DuPont Fellows". DuPont Media Center (Press release). July 17, 2014. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lewandowski, Thomas A. (July 24, 2013). "Additional risk assessment of alternative refrigerant R-1234yf prepared for SAE International cooperative research program CRP1234-4" (PDF). SAE International. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Directive 2006/40/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 relating to emissions from air-conditioning systems in motor vehicles and amending Council Directive 70/156/EEC". EFCTC. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Honeywell's low-global-warming refrigerant for vehicles approved for import, use by Japan regulators". Honeywell (Press release). August 4, 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Air conditioning in new vehicle models requires a greener gas". Autodata. 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Ansari, Naushad A.; Yadav, Bipin; Kumar, Jitendra (August 2013). "Theoretical exergy analysis of HFO-1234yf and HFO-1234ze as an alternative replacement of HFC-134a in simple vapour compression refrigeration system". International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 4 (8). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.415.9796.

- ↑ "HFO-1234yf, New Dawn of Refrigerant Alternatives". JARN: Japan Air Conditioning, Heating & Refrigeration News (Press release). April 25, 2008. pp. 1, 6, 24. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Gordon, Jacques (April 12, 2017). "Real world experience with R1234yf: The new refrigerant is finally here; are you ready?". Auto Service Professional. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Johnson, Alec (October 13, 2017). "Understanding refrigerant oils". Refrigerant HQ. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Automakers Go HFO", Chemical & Engineering News, July 26, 2010

- ↑ "Honeywell announces major investments to increase HFO-1234yf production in the United States". Honeywell (Press release). December 10, 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Honeywell starts up $300 million automotive refrigerant production facility in Louisiana". Honeywell (Press release). May 16, 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Marwa, Stefen (July 26, 2018). "HFO-1234yf market 2018 global share and projections: Honeywell and Chemours". The Aerospace News. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Hurley, M.D; Wallington, T.J; Javadi, M.S; Nielsen, O.J (2008). "Atmospheric chemistry of CF3CF=CH2: Products and mechanisms of Cl atom and OH radical initiated oxidation". Chemical Physics Letters. 450 (4–6): 263–267. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2007.11.051.

- ↑ Boutonnet, Jean Charles; Bingham, Pauline; Calamari, Davide; Rooij, Christ de; Franklin, James; Kawano, Toshihiko; Libre, Jean-Marie; McCul-Loch, Archie; Malinverno, Giuseppe; Odom, J Martin; Rusch, George M; Smythe, Katie; Sobolev, Igor; Thompson, Roy; Tiedje, James M (1999). "Environmental risk assessment of trifluoroacetic acid". International Journal of Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. 5 (1): 59–124. Bibcode:1999HERA....5...59B. doi:10.1080/10807039991289644.

- ↑ Henne, Albert L; Fox, Charles J (1951). "Ionization constants of fluorinated acids". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (5): 2323–2325. doi:10.1021/ja01149a122.

- ↑ "Refreshingly cool, potentially toxic". Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) Munich. 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Spatz, Mark; Minor, Barbara (July 2008). "HFO-1234yf Low GWP Refrigerant Update" (PDF).

- 1 2 Hetzner, Christiaan (December 12, 2012). "Coolant safety row puts the heat on Europe's carmakers". Reuters. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "SAE International Cooperative Research Project Offers Update on R1234yf Refrigerant". MACS Worldwide. December 14, 2012. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "A heated row over coolants". The Economist. August 31, 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Bolduc, Douglas A. (August 8, 2013). "German officials provide mixed ruling on Honeywell refrigerant Despite fire risk, agency does not seek recall of cars using HFO-1234yf". Automotive News Europe. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "GM first to market greenhouse gas-friendly air conditioning refrigerant in U.S." GM Corporate Newsroom (Press release). 2010-07-23. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 Schaeber, Steve (February 27, 2017). "R-1234yf at the 2017 PHL Auto Show". MACS Worldwide. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Zatz, David (October 1, 2013). "Chrysler adopting R1234YF". Allpar News (Press release). Retrieved 2018-06-16.

- ↑ "GMC hits the road with R-1234yf". MACS Worldwide. September 22, 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Schaeber, Steve (August 17, 2016). "Ford dealers selling their first MPVs with R-1234yf". MACS Worldwide. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Ask the expert: How many light duty OEs use HFO-1234yf refrigerant?". Vehicle Service Pros. May 15, 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "R134a alternative is "virtually non-flammable"". Cooling Post. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ↑ "US6969701B2 Azeotrope-like compositions of tetrafluoropropene and trifluoroiodomethane". Google patents. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Luecken, Deborah J.; Waterland, Robert L.; Papasavva, Stella; Taddonio, Kristen N.; Hutzell, William T.; Rugh, John P.; Andersen, Stephen O. (2010). "Ozone and TFA Impacts in North America from Degradation of 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene (HFO-1234yf), A Potential Greenhouse Gas Replacement". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (1): 343–348. Bibcode:2010EnST...44..343L. doi:10.1021/es902481f. PMID 19994849.