| Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 |

| Notable strains | |

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

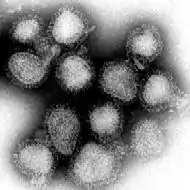

Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 (A/H3N2) is a subtype of viruses that causes influenza (flu). H3N2 viruses can infect birds and mammals. In birds, humans, and pigs, the virus has mutated into many strains. In years in which H3N2 is the predominant strain, there are more hospitalizations.[1]

Classification

H3N2 is a subtype of the viral genus Influenzavirus A, which is an important cause of human influenza. Its name derives from the forms of the two kinds of proteins on the surface of its coat, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). By reassortment, H3N2 exchanges genes for internal proteins with other influenza subtypes.[2]

Seasonal H3N2 flu

Seasonal influenza kills an estimated 36,000 people in the United States each year. Flu vaccines are based on predicting which "mutants" of H1N1, H3N2, H1N2, and influenza B will proliferate in the next season. Separate vaccines are developed for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres in preparation for their annual epidemics. In the tropics, influenza shows no clear seasonality. In the past ten years, H3N2 has tended to dominate in prevalence over H1N1, H1N2, and influenza B. Measured resistance to the standard antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine in H3N2 has increased from 1% in 1994 to 12% in 2003 to 91% in 2005.[3]

Seasonal H3N2 flu is a human flu from H3N2 that is slightly different from one of the previous year's flu season H3N2 variants. Seasonal influenza viruses flow out of overlapping epidemics in East Asia and Southeast Asia, then trickle around the globe before dying off. Identifying the source of the viruses allows global health officials to better predict which viruses are most likely to cause the most disease over the next year. An analysis of 13,000 samples of influenza A/H3N2 virus that were collected across six continents from 2002 to 2007 by the WHO's Global Influenza Surveillance Network showed the newly emerging strains of H3N2 appeared in East and Southeast Asian countries about six to nine months earlier than anywhere else. The strains generally reached Australia and New Zealand next, followed by North America and Europe. The new variants typically reached South America after an additional six to nine months, the group reported.[4]

Swine flu

A 2007 study reported: "In swine, three influenza A virus subtypes (H1N1, H3N2, and H1N2) are circulating throughout the world. In the United States, the classic H1N1 subtype was exclusively prevalent among swine populations before 1998; however, since late August 1998, H3N2 subtypes have been isolated from pigs. Most H3N2 virus isolates are triple reassortants, containing genes from human (HA, NA, and PB1), swine (NS, NP, and M), and avian (PB2 and PA) lineages. Present vaccination strategies for swine influenza virus (SIV) control and prevention in swine farms typically include the use of one of several bivalent SIV vaccines commercially available in the United States. Of the 97 recent H3N2 isolates examined, only 41 had strong serologic cross-reactions with antiserum to three commercial SIV vaccines. Since the protective ability of influenza vaccines depends primarily on the closeness of the match between the vaccine virus and the epidemic virus, the presence of nonreactive H3N2 SIV variants suggests current commercial vaccines might not effectively protect pigs from infection with a majority of H3N2 viruses."[5]

Avian influenza virus H3N2 is endemic in pigs in China, and has been detected in pigs in Vietnam, contributing to the emergence of new variant strains. Pigs can carry human influenza viruses, which can combine (i.e. exchange homologous genome subunits by genetic reassortment) with H5N1, passing genes and mutating into a form which can pass easily among humans. H3N2 evolved from H2N2 by antigenic shift and caused the Hong Kong Flu pandemic of 1968 and 1969 that killed up to 750,000 humans. The dominant strain of annual flu in humans in January 2006 was H3N2. Measured resistance to the standard antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine in H3N2 in humans had increased to 91% by 2005. In August 2004, researchers in China found H5N1 in pigs.[6]

Flu spread, by season

Hong Kong Flu (1968–1969)

The Hong Kong Flu was a flu pandemic caused by a strain of H3N2 descended from H2N2 by antigenic shift, in which genes from multiple subtypes reassorted to form a new virus. This pandemic of 1968 and 1969 killed an estimated one million people worldwide.[7][8][9] The pandemic infected an estimated 500,000 Hong Kong residents, 15% of the population, with a low death rate.[10] In the United States, about 100,000 people died.[11]

Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic flu strains contained genes from avian influenza viruses. The new subtypes arose in pigs coinfected with avian and human viruses and were soon transferred to humans. Swine were considered the original "intermediate host" for influenza, because they supported reassortment of divergent subtypes. However, other hosts appear capable of similar coinfection (e.g., many poultry species), and direct transmission of avian viruses to humans is possible. H1N1 may have been transmitted directly from birds to humans (Belshe 2005).[12]

The Hong Kong flu strain shared internal genes and the neuraminidase with the 1957 Asian flu (H2N2). Accumulated antibodies to the neuraminidase or internal proteins may have resulted in much fewer casualties than most pandemics. However, cross-immunity within and between subtypes of influenza is poorly understood.

The Hong Kong flu was the first known outbreak of the H3N2 strain, though there is serologic evidence of H3N2 infections in the late 19th century. The first record of the outbreak in Hong Kong appeared on 13 July 1968 in an area with a density of about 500 people per acre in an urban setting. The outbreak reached maximum intensity in two weeks, lasting six weeks in total. The virus was isolated in Queen Mary Hospital. Flu symptoms lasted four to five days.[10]

By July 1968, extensive outbreaks were reported in Vietnam and Singapore. By September 1968, it reached India, the Philippines, northern Australia and Europe. That same month, the virus entered California from United States troops returning from the Vietnam War. It reached Japan, Africa and South America in 1969.[10]

Fujian flu (2003–2004)

Fujian flu refers to flu caused by either a Fujian human flu strain of the H3N2 subtype or a Fujian bird flu strain of the H5N1 subtype of the Influenza A virus. These strains are named after Fujian province in China.

A/Fujian (H3N2) human flu (from A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2)-like flu virus strains) caused an unusually severe 2003–2004 flu season. This was due to a reassortment event that caused a minor clade to provide a haemagglutinin gene that later became part of the dominant strain in the 2002–2003 flu season. A/Fujian (H3N2) was made part of the trivalent influenza vaccine for the 2004–2005 flu season.[13]

2004–2005 flu season

The 2004–05 trivalent influenza vaccine for the United States contained:

- an A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Fujian/411/2002 (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Shanghai/361/2002-like virus.[13]

2005–2006 flu season

The vaccines produced for the 2005–2006 season used:

2006–2007 flu season

The 2006–2007 influenza vaccine composition recommended by the World Health Organization on 15 February 2006 and the US FDA's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee on 17 February 2006 used:

- an A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2)-like virus (A/Wisconsin/67/2005 and A/Hiroshima/52/2005 strains)

- a B/Malaysia/2506/2004-like virus from B/Malaysia/2506/2004 and B/Ohio/1/2005 strains which are of B/Victoria/2/87 lineage[14]

2007–2008 flu season

The composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2007–2008 Northern Hemisphere influenza season recommended by the World Health Organization on 14 February 2007[15] was:

- an A/Solomon Islands/3/2006 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2)-like virus (A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2) and A/Hiroshima/52/2005 were used at the time)

- a B/Malaysia/2506/2004-like virus[16][17]

"A/H3N2 has become the predominant flu subtype in the United States, and the record over the past 25 years shows that seasons dominated by H3N2 tend to be worse than those dominated by type A/H1N1 or type B." Many H3N2 viruses making people ill in this 2007–2008 flu season differ from the strains in the vaccine and may not be well covered by the vaccine strains. "The CDC has analyzed 250 viruses this season to determine how well they match up with the vaccine, the report says. Of 65 H3N2 isolates, 53 (81%) were characterized as A/Brisbane/10/2007-like, a variant that has evolved [notably] from the H3N2 strain in the vaccine—A/Wisconsin/67/2005."[18]

2008–2009 flu season

The composition of virus vaccines for use in the 2008–2009 Northern Hemisphere influenza season recommended by the World Health Organization on February 14, 2008[19] was:

- an A/Brisbane/59/2007 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Brisbane/10/2007 (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Florida/4/2006-like virus (B/Florida/4/2006 and B/Brisbane/3/2007 (a B/Florida/4/2006-like virus) were used at the time)[20][21]

As of May 30, 2009: "CDC has antigenically characterized 1,567 seasonal human influenza viruses [947 influenza A (H1), 162 influenza A (H3) and 458 influenza B viruses] collected by U.S. laboratories since October 1, 2008, and 84 novel influenza A (H1N1) viruses. All 947 influenza seasonal A (H1) viruses are related to the influenza A (H1N1) component of the 2008–09 influenza vaccine (A/Brisbane/59/2007). All 162 influenza A (H3N2) viruses are related to the A (H3N2) vaccine component (A/Brisbane/10/2007). All 84 novel influenza A (H1N1) viruses are related to the A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) reference virus selected by WHO as a potential candidate for novel influenza A (H1N1) vaccine. Influenza B viruses currently circulating can be divided into two distinct lineages represented by the B/Yamagata/16/88 and B/Victoria/02/87 viruses. Sixty-one influenza B viruses tested belong to the B/Yamagata lineage and are related to the vaccine strain (B/Florida/04/2006). The remaining 397 viruses belong to the B/Victoria lineage and are not related to the vaccine strain."[22]

2009–2010 flu season

The vaccines produced for the 2009–2010 season used:

- an A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Brisbane/10/2007 (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Brisbane 60/2008-like antigens[23]

A separate vaccine was available for pandemic H1N1 influenza using the A/California/7/2009-like pandemic H1N1 strain.[24]

2010–2011 flu season

The vaccines produced for the 2010–2011 season used:

- an A/California/7/2009-like (pandemic H1N1)

- an A/Perth/16/2009-like (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like antigens[24]

2011–2012 flu season

The vaccines produced for the 2011–2012 season used:

- an A/California/07/2009 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Victoria/210/2009 (an A/Perth/16/2009-like strain) (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus[25]

2012–2013 flu season

The vaccines produced for the Northern Hemisphere 2012–2013 season used:

- an A/California/07/2009 (H1N1)-like virus

- an A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Massachusetts/2/2012-like virus,[26] which replaced B/Wisconsin/1/2010-like virus[27]

In January 2013, influenza activity continued to increase in the United States and most of the country experienced high levels of influenza-like-illness (ILI), according to CDC's latest FluView report. Reports of influenza-like-illness (ILI) are nearing what have been peak levels during moderately severe seasons, and CDC continues to recommend influenza vaccination and antiviral drug treatment when appropriate at this time. On January 9, 2013, the Boston Government declared a public health emergency for H3N2 influenza.[28]

2014–2015 flu season

The vaccines produced for the Northern Hemisphere 2014–2015 season used:

- A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Texas/50/2012 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Massachusetts/2/2012-like virus,[29]

Quadrivalent vaccines include a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus.[30] The CDC announced that drift variants of the A (H3N2) virus strain from the 2012–2013 potentially foretold a severe flu season for 2014–2015.[31][32]

2015–2016 flu season

The vaccines produced for the Northern Hemisphere 2015–2016 season used:

- A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus. (This is a B/Yamagata lineage virus)

The "Split Virion" vaccine distributed in 2016 contained the following strains of inactivated virus:

- A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09 - like strain (A/California/7/2009, NYMC X-179A)

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) - like strain (A/Hong Kong/4801/2014, NYMC X-263B)

- B/Brisbane/60/2008 - like strain (B/Brisbane/60/2008, wild type)[33]

2016–2017 flu season

- A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus,

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage)[34]

Quadrivalent influenza vaccine adds:

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like strain

2017–2018 flu season

- A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)

- B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage)[35]

Quadrivalent influenza vaccine adds

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like[B/Yamagata lineage]

2020-SH(southern hemisphere)

Quadrivalent-

A/Brisbane/02/2018 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

A/SouthAustralia/34/2019 (H3N2)-like virus

B/Washington/02/2019-like virus [B/Victoria lineage]

B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus [B/Yamagata lineage]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pinkbook | Influenza | Epidemiology of Vaccine Preventable Diseases | CDC". CDC. 2019-03-29. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

Greater number of hospitalizations during years that A(H3N2) is predominant

- ↑ Marozin, S.; Gregory, V.; Cameron, K.; Bennett, M.; Valette, M.; Aymard, M.; Foni, E.; Barigazzi, G.; Lin, Y.; Hay, A.YR 2002 (2002). "Antigenic and genetic diversity among swine influenza A H1N1 and H1N2 viruses in Europe". Journal of General Virology. 83 (4): 735–745. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-83-4-735. ISSN 1465-2099. PMID 11907321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ronald Ban This Season's Flu Virus Is Resistant to 2 Standard Drugs. New York Times. January 15, 2006

- ↑ CIDRAP Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine article Study: New seasonal flu strains launch from Asia published 16 April 2008

- ↑ René Gramer, Marie; Hoon Lee, Jee; Ki Choi, Young; Goyal, Sagar M.; Soo Joo, Han (2007). "Serologic and genetic characterization of North American H3N2 swine influenza A viruses". Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 71 (3): 201–206. PMC 1899866. PMID 17695595.

- ↑ WHO (28 October 2005). "H5N1 avian influenza: timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Paul, William E. (2008). Fundamental Immunology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1273. ISBN 9780781765190.

- ↑ "World health group issues alert Mexican president tries to isolate those with swine flu". Associated Press. April 25, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Mandel, Michael (April 26, 2009). "No need to panic ... yet Ontario officials are worried swine flu could be pandemic, killing thousands". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- 1 2 3 Starling, Arthur (2006). Plague, SARS, and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. HK University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-962-209-805-3.

- ↑ "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 Virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Chapter Two : Avian Influenza by Timm C. Harder and Ortrud Werner from excellent free on-line book Influenza Report 2006

- 1 2 CDC article Update: Influenza Activity—United States and Worldwide, 2003–04 Season, and Composition of the 2004–05 Influenza Vaccine published 2 July 2004

- ↑ CDC fluwatch Archived 2010-03-08 at the Library of Congress Web Archives B/Victoria/2/87 lineage

- ↑ "14 February 2007: WHO information meeting (Morning)". Archived from the original on January 14, 2007.

- ↑ Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2007–2008 northern hemisphere influenza season. WHO

- ↑ WHO—Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2007–2008 influenza season (PDF)

- ↑ CIDRAP Archived 2013-05-06 at the Wayback Machine article Flu widespread in 44 states, CDC reports published 15 February 2008

- ↑ "14 February 2008: Information meeting (Morning)". Archived from the original on 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "WHO website recommendation for 2008–2009 season". Archived from the original on March 13, 2008.

- ↑ WHO—Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2008–2009 influenza season Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- ↑ CDC article "2008–2009 Influenza Season Week 21 ending May 30, 2009" published May 30, 2009

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2009–2010 influenza season".

- 1 2 "Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report - Seasonal Influenza (Flu) - CDC". 2018-12-07.

- ↑ "U S Food and Drug Administration Home Page". 2019-08-27.

- ↑ "WHO recommends new B strain for next season's flu vaccine". Center for infectious Disease Research and Policy. 21 Feb 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2013 southern hemisphere influenza season". World Health Organization. 20 Sep 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Mayor declares flu emergency in Boston". Boston Herald. 9 Jan 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ "What You Should Know for the 2014-2015 Influenza Season". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "WHO - Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2014-2015 northern hemisphere influenza season". Archived from the original on February 25, 2014.

- ↑ "CDC Press Releases". January 2016.

- ↑ "Dr. Mark Dowell urges flu shots despite mutated h3n2 strain". Wyoming Medical Center. December 8, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ↑ "Inactivated Influenza Vaccine (Split Virion) BP - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". Archived from the original on 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ↑ Scutti, Susan (September 14, 2017). "What Australia's bad flu season means for Europe, North America". CNN. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ Blanton, Lenee; Wentworth, David E.; Alabi, Noreen; Azziz-Baumgartner, Eduardo; Barnes, John; Brammer, Lynnette; Burns, Erin; Davis, C. Todd; Dugan, Vivien G. (2017). "Update: Influenza Activity — United States and Worldwide, May 21–September 23, 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (39): 1043–1051. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6639a3. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 5720887. PMID 28981486.

Further reading

- Graphic showing H3N2 mutations, amino acid by amino acid, among 207 isolates completely sequenced by the Influenza Genome Sequencing Project.

- Influenza A (H3N2) Outbreak, Nepal

- Hot topic – Fujian-like strain A influenza

- New Scientist: Bird Flu

External links

- Influenza Research Database Database of influenza sequences and related information.