| Otomi | |

|---|---|

| Region | Mexico: México (state), Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Guanajuato, Querétaro, Tlaxcala, Michoacán |

| Ethnicity | Otomi |

Native speakers | 300,000 (2020 census)[1] |

Oto-Manguean

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | In Mexico through the General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples (in Spanish). |

| Regulated by | Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | oto |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:ote – Mezquital Otomiotl – Tilapa Otomiotm – Highland Otomiotn – Tenango Otomiotq – Querétaro Otomiots – Estado de México Otomiott – Temoaya Otomiotx – Texcatepec Otomiotz – Ixtenco Otomi |

| Glottolog | otom1300 Otomisout3168 Southwestern Otomi |

Otomi-speaking areas in Mexico | |

The Otomi languages within Oto-Manguean, number 3 (bright blue), north | |

Otomi (/ˌoʊtəˈmiː/ OH-tə-MEE; Spanish: Otomí [otoˈmi]) is an Oto-Pamean language spoken by approximately 240,000 indigenous Otomi people in the central altiplano region of Mexico.[2] Otomi consists of several closely related languages, many of which are not mutually intelligible. The word Hñähñu [hɲɑ̃hɲṹ] has been proposed as an endonym, but since it represents the usage of a single dialect, it has not gained wide currency. Linguists have classified the modern dialects into three dialect areas: the Northwestern dialects are spoken in Querétaro, Hidalgo and Guanajuato; the Southwestern dialects are spoken in the State of Mexico; and the Eastern dialects are spoken in the highlands of Veracruz, Puebla, and eastern Hidalgo and villages in Tlaxcala and Mexico states.

Like all other Oto-Manguean languages, Otomi is a tonal language, and most varieties distinguish three tones. Nouns are marked only for possessor; the plural number is marked with a definite article and a verbal suffix, and some dialects keep dual number marking. There is no case marking. Verb morphology is either fusional or agglutinating depending on the analysis.[cn 1] In verb inflection, infixation, consonant mutation, and apocope are prominent processes. The number of irregular verbs is large. A class of morphemes cross-references the grammatical subject in a sentence. These morphemes can be analysed as either proclitics or prefixes and mark tense, aspect and mood. Verbs are inflected for either direct object or dative object (but not for both simultaneously) by suffixes. Grammar also distinguishes between inclusive 'we' and exclusive 'we'.

After the Spanish conquest, Otomi became a written language when friars taught the Otomi to write the language using the Latin script; colonial period's written language is often called Classical Otomi. Several codices and grammars were composed in Classical Otomi. A negative stereotype of the Otomi promoted by the Nahuas and perpetuated by the Spanish resulted in a loss of status for the Otomi, who began to abandon their language in favor of Spanish. The attitude of the larger world toward the Otomi language started to change in 2003 when Otomi was granted recognition as a national language under Mexican law together with 61 other indigenous languages.

Name

Otomi comes from the Nahuatl word otomitl, which in turn possibly derived from an older word, totomitl "shooter of birds."[3] It is an exonym; the Otomi refer to their language as Hñähñú, Hñähño, Hñotho, Hñähü, Hñätho, Hyųhų, Yųhmų, Ñųhų, Ñǫthǫ, or Ñañhų, depending on the dialect.[3][4][cn 2] Most of those forms are composed of two morphemes, meaning "speak" and "well" respectively.[5]

The word Otomi entered the Spanish language through Nahuatl and describes the larger Otomi macroethnic group and the dialect continuum. From Spanish, the word Otomi has become entrenched in the linguistic and anthropological literature. Among linguists, the suggestion has been made to change the academic designation from Otomi to Hñähñú, the endonym used by the Otomi of the Mezquital Valley; however, no common endonym exists for all dialects of the language.[3][4][6]

History

Proto-Otomi period and later precolonial period

The Oto-Pamean languages are thought to have split from the other Oto-Manguean languages around 3500 BC. Within the Otomian branch, Proto-Otomi seems to have split from Proto-Mazahua ca. 500 AD. Around 1000 AD, Proto-Otomi began diversifying into the modern Otomi varieties.[7] Much of central Mexico was inhabited by speakers of the Oto-Pamean languages before the arrival of Nahuatl speakers; beyond this, the geographical distribution of the ancestral stages of most modern indigenous languages of Mexico, and their associations with various civilizations remain undetermined. It has been proposed that Proto-Otomi-Mazahua most likely was one of the languages spoken in Teotihuacan, the greatest Mesoamerican ceremonial center of the Classic period, the demise of which occurred ca. 600 AD.[8]

The Precolumbian Otomi people did not have a fully developed writing system. However, Aztec writing, largely ideographic, could be read in Otomi as well as Nahuatl.[8] The Otomi often translated names of places or rulers into Otomi rather than using the Nahuatl names. For example, the Nahuatl place name Tenochtitlān, "place of Opuntia cactus", was rendered as *ʔmpôndo in proto-Otomi, with the same meaning.[cn 3]

Colonial period and Classical Otomi

At the time of the Spanish conquest of central Mexico, Otomi had a much wider distribution than now, with sizeable Otomi speaking areas existing in the modern states of Jalisco and Michoacán.[9] After the conquest, the Otomi people experienced a period of geographical expansion as the Spaniards employed Otomi warriors in their expeditions of conquest into northern Mexico. During and after the Mixtón rebellion, in which Otomi warriors fought for the Spanish, Otomis settled areas in Querétaro (where they founded the city of Querétaro) and Guanajuato which previously had been inhabited by nomadic Chichimecs.[10] Because Spanish colonial historians such as Bernardino de Sahagún used primarily Nahua speakers primarily as sources for their histories of the colony, the Nahuas' negative image of the Otomi people was perpetuated throughout the colonial period. This tendency towards devaluing and stigmatizing the Otomi cultural identity relative to other Indigenous groups gave impetus to the process of language loss and mestizaje, as many Otomies opted to adopt the Spanish language and customs in search of social mobility.[11]

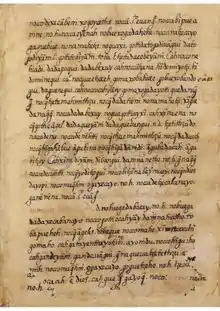

"Classical Otomi" is the term used to define the Otomi spoken in the early centuries of colonial rule. This historical stage of the language was given Latin orthography and documented by Spanish friars who learned it in order to proselytize among the Otomi. Text in Classical Otomi is not readily comprehensible since the Spanish-speaking friars failed to differentiate the varied vowel and consonant phonemes used in Otomi.[5] Friars and monks from the Spanish mendicant orders such as the Franciscans wrote Otomi grammars, the earliest of which is Friar Pedro de Cárceres's Arte de la lengua othomí [sic], written perhaps as early as 1580, but not published until 1907.[12][13][14] In 1605, Alonso de Urbano wrote a trilingual Spanish-Nahuatl-Otomi dictionary, which included a small set of grammatical notes about Otomi. The grammarian of Nahuatl, Horacio Carochi, has written a grammar of Otomi, but no copies have survived. He is the author of an anonymous dictionary of Otomi (manuscript 1640). In the latter half of the eighteenth century, an anonymous Jesuit priest wrote the grammar Luces del Otomi (which is, strictly speaking, not a grammar but a report on research about Otomi [15]). Neve y Molina wrote a dictionary and a grammar.[16] [17]

During the colonial period, many Otomis learned to read and write their language. Consequently, a significant number of Otomi documents exist from the period, both secular and religious, the most well-known of which are the Codices of Huichapan and Jilotepec.[cn 4] In the late colonial period and after independence, indigenous groups no longer had separate status. At that time, Otomi lost its status as a language of education, ending Classical Otomi period as a literary language.[5] This led to a declining numbers of speakers of indigenous languages, as Indigenous groups throughout Mexico adopted the Spanish language and Mestizo cultural identities. Coupled with a policy of castellanización this led to a rapid decline of speakers of all indigenous languages including Otomi, during the early 20th century.[18]

Contemporary status

| Region | Count | Percentage[cn 5] |

|---|---|---|

| Mexico City | 12,460 | 5.2% |

| Querétaro | 18,933 | 8.0% |

| Hidalgo | 95,057 | 39.7% |

| Mexico (state) | 83,362 | 34.9% |

| Jalisco | 1,089 | 0.5% |

| Guanajuato | 721 | 0.32% |

| Puebla | 7,253 | 3.0% |

| Michoacán | 480 | 0.2% |

| Nuevo León | 1,126 | 0.5% |

| Veracruz | 16,822 | 7.0% |

| Rest of Mexico | 2,537 | 1.20% |

| Total: | 239,850 | 100% |

During the 1990s, however, the Mexican government made a reversal in policies towards indigenous and linguistic rights, prompted by the 1996 adoption of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights[cn 6] and domestic social and political agitation by various groups such as social and political agitation by the EZLN and indigenous social movements. Decentralized government agencies were created and charged with promoting and protecting indigenous communities and languages; these include the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI).[19] In particular, the federal Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ("General Law on the Language Rights of the Indigenous Peoples"), promulgated on 13 March 2003, recognizes all of Mexico's indigenous languages, including Otomi, as "national languages", and gave indigenous people the right to speak them in every sphere of public and private life.[20]

Current speaker demography and vitality

Currently, Otomi dialects are spoken by circa 239,000 speakers—some 5 to 6 percent of whom are monolingual—in widely scattered districts (see map).[2] The highest concentration of speakers is found in the Valle de Mezquital region of Hidalgo and the southern portion of Querétaro. Some municipalities have concentrations of Otomi speakers as high as 60–70%.[21] Because of recent migratory patterns, small populations of Otomi speakers can be found in new locations throughout Mexico and the United States. In the second half of the 20th century, speaker populations began to increase again, although at a slower pace than the general population. While absolute numbers of Otomi speakers continue to rise, their numbers relative to the Mexican population are falling.[22]

Although Otomi is vigorous in some areas, with children acquiring the language through natural transmission (e.g. in the Mezquital valley and in the Highlands), it is an endangered language.[23] Three dialects in particular have reached moribund status: those of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala state), Santiago Tilapa (Mexico state), and Cruz del Palmar (Guanajuato state).[21] On the other hand, the level of monolingualism in Otomi is as high as 22.3% in Huehuetla, Hidalgo, and 13.1% in Texcatepec, Veracruz). Monolingualism is usually significantly higher among women than among men.[24] Due to the politics from the 1920s to the 1980s that encouraged the "Hispanification" of indigenous communities and made Spanish the only language used in schools,[18] no group of Otomi speakers today has general literacy in Otomi,[25] while their literacy rate in Spanish remains far below the national average.[cn 7]

Classification

The Otomi languages belongs to the Oto-Pamean branch of the Oto-Manguean languages. Within Oto-Pamean, it is part of the Otomian subgroup, which also includes Mazahua.[26][27]

Otomi has traditionally been described as a single language, although its many dialects are not all mutually intelligible. SIL International's Ethnologue considers nine separate Otomi languages based on literature needs and the degree of mutual intelligibility between varieties. It assigns an ISO code to each of these nine.[28] INALI, the Mexican National Institute of Indigenous Languages, avoids the problem of assigning dialect or language status to Otomian varieties by defining "Otomi" as a "linguistic group" with nine different "linguistic varieties".[cn 8] Still, for official purposes, each variety is considered a separate language.[29] Other linguists, however, consider Otomi to be a dialect continuum that is clearly demarcated from its closest relative, Mazahua.[7] For this article, the latter approach will be followed.

Dialectology

Dialectologists tend to group the languages into three main groups that reflect historical relationships among the dialects: Northwestern Otomi spoken in the Mezquital Valley and surrounding areas of Hidalgo, Queretaro and Northern Mexico State, Southwestern Otomi spoken in the valley of Toluca, and Eastern Otomi spoken in the Highlands of Northern Puebla, Veracruz and Hidalgo, in Tlaxcala and two towns in the Toluca Valley, San Jerónimo Acazulco and Santiago Tilapa. The Northwestern varieties are characterized by an innovative phonology and grammar, whereas the Eastern varieties are more conservative.[30][31][29]

The assignment of dialects to the three groups is as follows:[cn 9]

- The Eastern group, including all dialects spoken east of the Valle del Mezquital in the center of the State of Hidalgo plus two village dialects from the State of Mexico; specifically: the Highland dialects (the Ethnologue's Highland Otomi, Texcatepec Otomi, and Tenango Otomi), Otomi of Santa Ana Hueytlalpan, as well as three dialects geographically distant from the preceding: the dialects of Tilapa and Acazulco in the state of Mexico, and finally the dialect of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala).

- The Northwestern area, comprising the dialects of Mezquital, Querétaro, and Guanajuato.

- The Southwestern group, including the so called State of Mexico dialect, Otomi of Chapa de Mota, Otomi of Jilotepec, Toluca Otomi, and Otomi of San Felipe los Alzatí, Michoacán. (In point of fact, all the foregoing, except of course for Alzatí, are spoken in the northern half of western lobe of the State of Mexico.)

| Approximate number of speakers of all varieties of Otomí: ~212,000 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otomi language | Where spoken | Own name | ISO 639-3 | Number of speakers |

| Highland Otomi | Hidalgo, Puebla, Veracruz | Yųhų[32] | otm | 20,000 |

| Mezquital Otomi | Hidalgo Mezquital Valley, and 100 in North Carolina, 230 in Oklahoma and 270 in Texas United States | Hñahñu[32] | ote | 100,000 |

| Otomi del Estado de Mexico | N México (state): San Felipe Santiago | Hñatho, Hñotho[32] | ots | 10,000 |

| Otomi de Tlaxcala | Tlaxcala: San Juan Bautista Ixtenco | Yųhmų[33] | otz | 736 |

| Otomi de Texcatepec | Northwestern Veracruz: Texcatepec, Ayotuxtla, Zontecomatlán Municipio: Hueytepec, Amajac, Tzicatlán. | Ñųhų[33] | otx | 12,000 |

| Otomí de Queretaro | Querétaro: Amealco Municipio: towns of San Ildefonso, Santiago Mexquititlán; Acambay Municipio; Tolimán Municipio. Also small numbers in Guanajuato. | Hñohño, Ñañhų, Hñąñho, Ñǫthǫ [34] | otq | 33,000 |

| Otomi de Tenango | Hidalgo, Puebla: San Nicolás Tenango | Ñųhų[34] | otn | 10,000 |

| Otomí de Tilapa | Santiago Tilapa town between D.F. and Toluca, State of México | Ñųhų[34] | otl | 100 |

| Temoaya Otomi | Temoaya Municipio, State of México | Ñatho[34] | ott | 37,000 |

Mutual intelligibility

| 70% | Egland & Bartholomew | Ethnologue 16 |

|---|---|---|

| * | Tolimán (less Tecozautla) | Querétaro (incl. Mexquititlán) |

| Anaya (+ Zozea, Tecozautla) | Mezquital | |

| San Felipe | (N: San Felipe) State of Mexico; (S: Jiquipilco) Temoaya | |

| * | — | Tilapa |

| * | Texcatepec | Texcatepec |

| San Antonio – San Gregorio | Eastern Highland | |

| San Nicolás | Tenango | |

| * | Ixtenco | Ixtenco |

Egland, Bartholomew & Cruz Ramos (1983) conducted mutual intelligibility tests in which they concluded that eight varieties of Otomi could be considered separate languages in regards to mutual intelligibility, with 80% intelligibility being needed for varieties to be considered part of the same language. They concluded that Texcatepec, Eastern Highland Otomi, and Tenango may be considered the same language at a lower threshold of 70% intelligibility. Ethnologue finds a similar lower level of 70% intelligibility between Querétaro, Mezquital, and Mexico State Otomi. The Ethnologue Temaoya Otomi is split off from Mexico State Otomi, and introduce Tilapa Otomi as a separate language; while Egland's poorly tested Zozea Otomi is subsumed under Anaya/Mezquital.

Phonology

Phoneme inventory

The following phonological description is that of the dialect of San Ildefonso Tultepec, Querétaro, similar to the system found in the Valle del Mezquital variety, which is the most widely spoken Otomian variety.[cn 10]

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | ejective | tʼ | tsʼ | tʃʼ | kʼ | ||

| unaspirated | p | t | t͡s | t͡ʃ | k | ʔ | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | ɸ | θ | s | ʃ | x | h |

| voiced | z | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Liquid | rhotic | r~ɾ | |||||

| lateral | l | ||||||

| Semivowel | w | j | |||||

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | i | ĩ | ɨ | u | ũ | |

| Close-mid | e | ə | o | õ | ||

| Near-open | ɛ | ɛ̃ | ɔ | |||

| Open | a | ã | ||||

The phoneme inventory of the Proto-Otomi language from which all modern varieties have descended has been reconstructed as /p t k (kʷ) ʔ b d ɡ t͡s ʃ h z m n w j/, the oral vowels /i ɨ u e ø o ɛ a ɔ/, and the nasal vowels /ĩ ũ ẽ ɑ̃/.[35][36][37]

Phonological diversity of the modern dialects

Modern dialects have undergone various changes from the common historic phonemic inventory. Most have voiced the reconstructed Proto-Otomian voiceless nonaspirate stops /p t k/ and now have only the voiced series /b d ɡ/. The only dialects to retain all the original voiceless nonaspirate stops are Otomi of Tilapa and Acazulco and the eastern dialect of San Pablito Pahuatlan in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, and Otomi of Santa Ana Hueytlalpan.[38] A voiceless aspirate stop series /pʰ tʰ kʰ/, derived from earlier clusters of stop + [h], occurs in most dialects, but it has turned into the fricatives /ɸ θ x/ in most Western dialects. Some dialects have innovated a palatal nasal /ɲ/ from earlier sequences of *j and a nasal vowel.[21] In several dialects, the Proto-Otomi clusters *ʔm and *ʔn before oral vowels have become /ʔb/ and /ʔd/, respectively.[14] In most dialects *n has become /ɾ/, as in the singular determiner and the second person possessive marker. The only dialects to preserve /n/ in these words are the Eastern dialects, and in Tilapa these instances of *n have become /d/.[38]

Many dialects have merged the vowels *ɔ and *a into /a/ as in Mezquital Otomi, whereas others such as Ixtenco Otomi have merged *ɔ with *o. The different dialects have between three and five nasal vowels. In addition to the four nasal vowels of proto-Otomi, some dialects have /õ/. Ixtenco Otomi has only /ẽ ũ ɑ̃/, whereas Toluca Otomi has /ĩ ũ ɑ̃/. In the Otomi of Cruz del Palmar, Guanjuato, the nasal vowels are /ĩ ũ õ/, the former *ɑ̃ having changed to /õ/.[cn 11] Modern Otomi has borrowed many words from Spanish, in addition to new phonemes that occur only in loan words, such as /l/ that appears in some Otomi dialects instead of the Spanish trilled [r], and /s/, which is not present in native Otomi vocabulary either.[39][40]

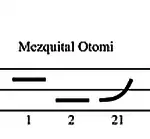

Tone and stress

All Otomi languages are tonal, and most varieties have three tones, high, low and rising.[14][cn 12] One variety of the Sierra dialect, that of San Gregorio, has been analyzed as having a fourth, falling tone.[41] In Mezquital Otomi, suffixes are never specified for tone,[42] while in Tenango Otomi, the only syllables not specified for tone are prepause syllables and the last syllable of polysyllabic words.

Stress in Otomi is not phonemic but rather falls predictably on every other syllable, with the first syllable of a root always being stressed.[43]

Orthography

In this article, the orthography of Lastra (various, including 1996, 2006) is employed which marks syllabic tone. The low tone is unmarked (a), the high level tone is marked with the acute accent (á), and the rising tone with the caron (ǎ). Nasal vowels are marked with a rightward curving hook (ogonek) at the bottom of the vowel letter: į, ę, ą, ų. The letter c denotes [t͡s], y denotes [j], the palatal sibilant [ʃ] is written with the letter š, and the palatal nasal [ɲ] is written ñ. The remaining symbols are from the IPA with their standard values.

Classical Otomi

Colonial documents in Classical Otomi do not generally capture all the phonological contrasts of the Otomi language. Since the friars who alphabetized the Otomi populations were Spanish speakers, it was difficult for them to perceive contrasts that were present in Otomi but absent in Spanish, such as nasalisation, tone, the large vowel inventory as well as aspirated and glottal consonants. Even when they recognized that there were additional phonemic contrasts in Otomi they often had difficulties choosing how to transcribe them and with doing so consistently. No colonial documents include information on tone. The existence of nasalization is noted by Cárceres, but he does not transcribe it. Cárceres used the letter æ for the low central unrounded vowel [ʌ] and æ with cedille for the high central unrounded vowel ɨ.[44] He also transcribed glottalized consonants as geminates e.g. ttz for [t͡sʔ].[44] Cárceres used grave-accented vowels è and ò for [ɛ] and [ɔ]. In the 18th century Neve y Molina used vowels with macron ē and ō for these two vowels and invented extra letters (an e with a tail and a hook and an u with a tail) to represent the central vowels.[45]

Practical orthography for modern dialects

HOGÄ EHE NTS'U̲TK'ANI

CORAZON DEL VALLE DEL MEZQUITAL

Orthographies used to write modern Otomi have been a focus of controversy among field linguists for many years. Particularly contentious is the issue of whether or not to mark tone, and how, in orthographies to be used by native speakers. Many practical orthographies used by Otomi speakers do not include tone marking. Bartholomew[46] has been a leading advocate for the marking of tone, arguing that because tone is an integrated element of the language's grammatical and lexical systems, the failure to indicate it would lead to ambiguity. Bernard (1980) on the other hand, has argued that native speakers prefer a toneless orthography because they can almost always disambiguate using context, and because they are often unaware of the significance of tone in their language, and consequently have difficulty learning to apply the tone diacritics correctly. For Mezquital Otomi, Bernard accordingly created an orthography in which tone was indicated only when necessary to disambiguate between two words and in which the only symbols used were those available on a standard Spanish language typewriter (employing for example the letter c for [ɔ], v for [ʌ], and the symbol + for [ɨ]). Bernard's orthography has not been influential and in used only in the works published by himself and the Otomi author Jesus Salinas Pedraza.[47][48]

Practical orthographies used to promote Otomi literacy have been designed and published by the Instituto Lingüístico de Verano[cn 13] and later by the national institute for indigenous languages (INALI). Generally they use diareses ë and ö to distinguish the low mid vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ] from the high mid vowels e and o. High central vowel [ɨ] is generally written ʉ or u̱, and front mid rounded vowel [ø] is written ø or o̱. Letter a with trema, ä, is sometimes used for both the nasal vowel [ã] and the low back unrounded vowel [ʌ]. Glottalized consonants are written with apostrophe (e.g. tz' for [t͡sʔ]) and palatal sibilant [ʃ] is written with x.[49] This orthography has been adopted as official by the Otomi Language Academy centered in Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo and is used on road signs in the Mezquital region and in publications in the Mezquital variety, such as the large 2004 SIL dictionary published by Hernández Cruz, Victoria Torquemada & Sinclair Crawford (2004). A slightly modified version is used by Enrique Palancar in his grammar of the San Ildefonso Tultepec variety.[50]

Grammar

The morphosyntactic typology of Otomi displays a mixture of synthetic and analytic structures. The phrase level morphology is synthetic, and the sentence level is analytic.[40] Simultaneously, the language is head-marking in terms of its verbal morphology, and its nominal morphology is more analytic.

According to the most common analysis, Otomi has two kinds of bound morphemes, proclitics and affixes. Proclitics differ from affixes mainly in their phonological characteristics; they are marked for tone and block nasal harmony. [51] Some authors consider proclitics to be better analyzed as prefixes.[52][53] The standard orthography writes proclitics as separate words, whereas affixes are written joined to their host root. Most affixes are suffixes and with few exceptions occur only on verbs, whereas the proclitics occur both in nominal and verbal paradigms. Proclitics mark the categories of definiteness and number, person, negation, tense and aspect – often fused in a single proclitic. Suffixes mark direct and indirect objects as well as clusivity (the distinction between inclusive and exclusive "we"), number, location and affective emphasis. Historically, as in other Oto-Manguean languages, the basic word order is Verb Subject Object, but some dialects tend towards Subject Verb Object word order, probably under the influence of Spanish.[40] Possessive constructions use the order possessed-possessor, but modificational constructions use modifier-head order.

From the variety of Santiago Mexquititlan, Queretaro, here is an example of a complex verb phrase with four suffixes and a proclitic:

Bi=hon-ga-wi-tho-wa

"He/she looks for us only (around) here"[54]

The initial proclitic bi marks the present tense and the third person singular, the verb root hon means "to look for", the -ga- suffix marks a first person object, the -wi- suffix marks dual number, and tho marks the sense of "only" or "just" whereas the -wa- suffix marks the locative sense of "here".

Pronominal system: Person and Number

Originally, all dialects distinguished singular, dual and plural numbers, but some of the more innovative dialects, such as those of Querétaro and of the Mezquital area, distinguish only singular and plural numbers, sometimes using the previous dual forms as a paucal number.[55] The Ixtenco dialect distinguishes singular, plural, and mass plural numbers.[56][57] The personal prefixes distinguish four persons, making for a total of eleven categories of grammatical person in most dialects.[21] The grammatical number of nouns is indicated by the use of articles; the nouns themselves are unmarked for number.

In most dialects, the pronominal system distinguishes four persons (first person inclusive and exclusive, second person and third person) and three numbers (singular, dual and plural). The system below is from the Toluca dialect.[58]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person Incl. | * | nugóbé 'you and I' | nugóhé 'I and you guys' |

| 1st Person Excl. | nugó 'I' | nugówí 'we two (not you)' | nugóhɨ́ 'We all (not you)' |

| 2nd Person | nukʔígé 'you' | nukʔígéwí 'you two' | nukʔígégɨ́ 'you guys' |

| 3rd Person | gégé 'she/he/it' | nugégéwí 'the two of them' | nugégéhɨ́ 'they' |

The following atypical pronominal system from Tilapa Otomi lacks the inclusive/exclusive distinction in the first person plural and the dual/plural distinction in the second person.[59]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person Excl. | * | nyugambe 'we two (not you)' | nyugahɨ́ 'we all (both incl and excl.)' |

| 1st Person Incl. | nyugá 'I' | nugawi 'you and I' | * |

| 2nd Person | nyukʔe 'you' | nyukʔewi 'you two' | nyukʔehɨ́ 'you guys' |

| 3rd Person | nyuaní 'she/he/it' | * | nyuyí 'they' (both dual and plural) |

Nouns

Otomi nouns are marked only for their possessor; plurality is expressed via pronouns and articles. There is no case marking. The particular pattern of possessive inflection is a widespread trait in the Mesoamerican linguistic area: there is a prefix agreeing in person with the possessor, and if the possessor is plural or dual, then the noun is also marked with a suffix that agrees in number with the possessor. Demonstrated below is the inflectional paradigm for the word ngų́ "house" in the dialect of Toluca.[58]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person Excl. | * | mą-ngų́-bé 'our house (me and him/her)' | mą-ngų́-hé 'our house (me and them)' |

| 1st Person Incl. | mą-ngų́ 'my house' | mą-ngų́-wí 'our house (me and you)' | mą-ngų́-hɨ́ 'our house (me and you and them)' |

| 2nd Person | ri-ngų́ 'your house' | ri-ngų́-wí 'the house of the two of you' | ri-ngų́-hɨ́ 'the house of you guys' |

| 3rd Person | rʌ-ngų́ 'her/his/its house' | yʌ-ngų́-wí 'the house of the two of them' | yʌ-ngų́-hɨ́ 'their house' |

Articles

Definite articles preceding the noun are used to express plurality in nominal elements, since the nouns themselves are invariant for grammatical number. Most dialects have rʌ 'the (singular)' and yʌ 'the (dual/plural)'. Example noun phrases:

| Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| rʌ ngų́ 'the house' | yʌ yóho ngų́ 'the two houses' | yʌ ngų́ 'the houses' |

Classical Otomi, as described by Cárceres, distinguished neutral, honorific, and pejorative definite articles: ąn, neutral singular; o, honorific singular; nø̌, pejorative singular; e, neutral and honorific plural; and yo, pejorative plural.[14]

- ąn ngų́ 'the house'

- o ngų́ 'the honored house'

- nø̌ ngų́ 'the damn house'

Verbs

Verb morphology is synthetic and has elements of both fusion and agglutination.[cn 1][60]

Verb stems are inflected through a number of different processes: the initial consonant of the verb root changes according to a morphophonemic pattern of consonant mutations to mark present vs. non-present, and active vs. passive.[50][61] Verbal roots may take a formative syllable or not depending on syntactic and prosodic factors.[62] A nasal prefix may be added to the root to express reciprocality or middle voice.[63] Some dialects, notably the eastern ones, have a system of verb classes that take different series of prefixes. These conjugational categories have been lost in the Western dialects, although they existed in the Western areas in the colonial period as can be seen from Cárceres's grammar.[29]

Verbs are inflected for either direct object or indirect object (but not for both simultaneously) by suffixes. The categories of person of subject, tense, aspect, and mood are marked simultaneously with a formative which is either a verbal prefix or a proclitic depending on analysis.[40][64] These proclitics can also precede nonverbal predicates.[41][65] The dialects of Toluca and Ixtenco distinguish the present, preterit, perfect, imperfect, future, pluperfect, continuative, imperative, and two subjunctives. Mezquital Otomi has additional moods.[66] On transitive verbs, the person of the object is marked by a suffix. If either subject or object is dual or plural, it is shown with a plural suffix following the object suffix. So the structure of the Otomi verb is as follows:

| Person of Subject/TAM (proclitic) | Prefixes (e.g. voice, adverbial modification) | Root | formative | Object suffix | 1st person emphatic suffix | Plural/Dual suffix |

Person, number, tense, aspect and mood

The present tense prefixes are di- (1st person), gi- (2nd person), i- (3rd person).

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person Excl. | * | di-nú-bé 'we see (me and him/her)' | di-nú-hé 'we see (me and them)' |

| 1st Person Incl. | di-nú 'I see' | di-nú-wí 'we see (me and you)' | mdi-nú-hɨ́ 'we see (me and you and them)' |

| 2nd Person | gi-nú 'you see' | gi-nú-wí 'you two see' | gi-nú-hɨ́ 'you guys see' |

| 3rd Person | i-nú 'she/he/it sees' | i-nú-wí 'the two of them see' | i-nú-hɨ́ 'they see' |

The Preterite is marked by the prefixes do-, ɡo-, and bi-, the Perfect by to-, ko-, ʃi-, the Imperfect bydimá, ɡimá, mi, the Future by ɡo-, ɡi-, and da-, and the Pluperfect by tamą-, kimą-, kamą-. All tenses use the same suffixes as the Present tense for dual and plural numbers and clusivity. The difference between Preterite and Imperfect is similar to the distinction between the Spanish Preterite habló 'he spoke (punctual)' and the Spanish Imperfect hablaba 'he spoke/he used to speak/he was speaking (non-punctual)'.

In Toluca Otomi, the semantic difference between the two subjunctive forms (A and B) has not yet been clearly understood in the linguistic literature. Sometimes subjunctive B implicates that is more recent in time than subjunctive A. Both indicate something counterfactual. In other Otomi dialects, such as Otomi of Ixtenco Tlaxcala, the distinction between the two forms is one of subjunctive as opposed to irrealis.[66][67] The Past and Present Progressive are similar in meaning to English 'was' and 'is X-ing', respectively. The Imperative is used for issuing direct orders.

Verbs expressing movement towards the speaker such as ʔįhį 'come' use a different set of prefixes for marking person/TAM. These prefixes can also be used with other verbs to express 'to do something while coming this way'. In Toluca Otomi mba- is the third person singular Imperfect prefix for movement verbs.

mba-tųhų

3/MVMT/IMPERF-sing

'he came singing'[68]

When using nouns predicatively, the subject prefixes are simply added to the noun root:

drʌ-mǒkhá

1SG/PRES/CONT-priest

'I am a priest'[68]

Transitivity and stative verbs

Transitive verbs are inflected for agreement with their objects by means of suffixes, while using the same subject prefixes as the intransitive verbs to agree with their agents. However, in all dialects a few intransitive verbs take the object suffix instead of the subject prefix. Often such intransitive verbs are stative, i.e. describing a state, which has prompted the interpretation that morphosyntactic alignment in Otomi is split between active–stative and accusative systems.[65]

In Toluca Otomi the object suffixes are -gí (first person), -kʔí (second person) and -bi (third person), but the vowel /i/ may harmonize to /e/ when suffixed to a root containing /e/. The first person suffix is realized as -kí after sibilants and after certain verb roots, and as -hkí when used with certain other verbs. The second person object suffix may sometimes metathesise to -ʔkí. The third person suffix also has the allomorphs -hpí/-hpé, -pí, -bí as well as a zero morpheme in certain contexts.[69]

| 1st person object | 2nd person object | 3rd person object |

|---|---|---|

bi-ñús-kí he/PAST-write-me 'he wrote me' |

bi-ñús-kʔí he/PAST-write-you 'he wrote you' |

bi-kré-bi he/PAST-believe-it 'he believed it' |

bi-nú-gí he/PAST-see-me 'he saw me' |

bi-nú-kʔí he/PAST-see-you 'he saw you' |

bi-hkwáhti-bí he/she/PAST-hit-him/her 'she/he hit him/her' |

Object number (dual or plural) is marked by the same suffixes that are used for the subject, which can lead to ambiguity about the respective numbers of subject and object. With object suffixes of the first or second person, the verbal root sometimes changes, often by the deletion of the final vowel. For example:[70]

| dual object/subject | plural object/subject |

|---|---|

bi-ñaš-kʔí-wí he/PAST-cut.hair-you-DU 'the two of them cut your hair' or |

bi-ñaš-kí-hɨ́ he/PAST-cut.hair-you-PL 'they cut my hair' or 'he cut our hair' |

A word class that refers to properties or states has been described either as adjectives[71] or as stative verbs.[65][72] The members of this class ascribe a property to an entity, e.g. "the man is tall", "the house is old". Within this class some roots use the normal subject/T/A/M prefixes, while others always use the object suffixes to encode the person of the patient/subject. The fact that roots in the latter group encode the patient/subject of the predicate using the same suffixes as transitive verbs use to encode the patient/object has been interpreted as a trait of Split intransitivity,[65] and is apparent in all Otomi dialects; but which specific stative verbs take the object prefixes and the number of prefixes they take varies between dialects. In Toluca Otomi, most stative verbs are conjugated using a set of suffixes similar to the object/patient suffixes and a third person subject prefix, while only a few use the Present Continuative subject prefixes. The following are examples of the two kinds of stative verb conjugation in Toluca Otomi:[73]

| with patient/object suffix | with subject/agent prefix |

|---|---|

rʌ-nǒ-hkʔí it/PRES-fat-me 'I am fat' |

drʌ-dǒtʔî I/PRES/CONT-short 'I am short' |

Syntax

Otomi has the nominative–accusative alignment, but by one analysis there are traces of an emergent active–stative alignment.[65]

Word order

Some dialects have SVO as the most frequent word order, for example Otomi of Toluca[74] and of San Ildefonso, Querétaro,[75] while VSO word order is basic to other dialects such as Mezquital Otomi.[76] Proto-Otomi is also thought to have had VSO order as verb-initial order is the most frequent basic word order in other Oto-Manguean languages. It has been suggested that some Otomi dialects are shifting from a verb-initial to a subject-initial basic word order under the influence of Spanish.[77]

Clause types

Lastra (1997:49–69) describes the clause types in Ixtenco Otomi. The four basic clause types are indicative, negative, interrogative and imperative. These four types can either be simple, conjunct or complex (with a subordinate clause). Predicative clauses can be verbal or non-verbal. Non-verbal predicative clauses are usually equational or ascriptive (with the meaning 'X is Y'). In a non-vebal predicative clause the subject precedes the predicate, except in focus constructions where the order is reversed. The negation particle precedes the predicate.

ni-ngú

your-house

ndɨ^té

big

'your house is big'

thɛ̌ngɨ

red

ʔnį́

pepper

'its red, the pepper' (focus)

Equational clauses can also be complex:

títa

sweathouse

habɨ

where

ditá

bathe

yɨ

the

khą́

people

ʔí

'the sweat house is where people bathe' Mismatch in the number of words between lines: 6 word(s) in line 1, 5 word(s) in line 2 (help);

Clauses with a verb can be intransitive or transitive. In Ixtenco Otomi, if a transitive verb has two arguments represented as free noun phrases, the subject usually precedes the verb and the object follows it.

ngé

so

rʌ

the

ñôhɨ

man

šʌ-hió

killed

rʌ

the

ʔyo

dog

"the man killed the dog"

This order is also the norm in clauses where only one constituent is expressed as a free noun phrase. In Ixtenco Otomi verb-final word order is used to express focus on the object, and verb-initial word order is used to put focus on the predicate.

ngɨ^bo

brains

di-pho-mi

we-have-them

ma-ʔya-wi

our-heads-PL

"our brains, we have them in our heads" (focus on object)

Subordinate clauses usually begin with one of the subordinators such as khandi 'in order to', habɨ 'where', khati 'even though', mba 'when', ngege 'because'. Frequently the future tense is used in these subordinate clause. Relative clauses are normally expressed by simple juxtaposition without any relative pronoun. Different negation particles are used for the verbs "to have", "to be (in a place)" and for imperative clauses.

- hingi pá che ngege po na chú "(s)he doesn't go alone because (s)he's afraid"

Interrogative clauses are usually expressed by intonation, but there is also a question particle ši. Content questions use an interrogative pronoun before the predicate.

té

what

bi-khá-nɨ́

it-is

what's that?'

Numerals

Like all other languages of the Mesoamerican linguistic area, Otomi has a vigesimal number system. The following numerals are from Classical Otomi as described by Cárceres. The e prefixed to all numerals except one is the plural nominal determiner (the a associated with -nʔda being the singular determiner).[14]

- 1 anʔda

- 2 eyoho

- 3 ehių

- 4 ekoho

- 5 ekɨtʔa

- 6 eʔdata

- 7 eyoto

- 8 ehyąto

- 9 ekɨto

- 10 eʔdɛta

- 11 eʔdɛta ma ʔda

- 20 eʔdote

- 40 eyote

- 60 ehyąte

Vocabulary

There are also considerable lexical differences between the Otomi dialects. Often terms will be shared between the eastern and southwestern dialects, while the northwestern dialects tend toward more innovative forms.[cn 14]

| Gundhó (Mezquital) | San Ildefonso, Amealco | Toluca | Tilapa | Ixtenco | Huehuetla (Highland) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paper | hɛ̌ʔmí | hɛ̌ʔmi | cųhkwá | cɨ̌hkó | cuhkwá | cø̌hkwą́ |

| mother | ną́ną́ | nóno | mé | mbé | ną́ną́ | mbé |

| metal | bɛkhá[cn 15] | bøkhǫ́ | tʔéɡí | tʔɛ̌ɡi | tʔɛɡi | tʔɛ̌ki |

| money | bokhą́ | bokhǫ́ | domi[cn 16] | mbɛhti | tʔophó | tʔophó[cn 17] |

| much/a lot | ndųnthį́ | nzɛya | dúnthí | pongí | chú | ʃøngų́ |

Loan words

Otomi languages have borrowed words from both Spanish and Nahuatl. The phonological structure of loanwords is assimilated to Otomi phonology. Since Otomi lacks the trill /r/, this sound is normally altered to [l], as in lódá from Spanish ruda 'rue (medicinal herb)', while Spanish /l/ can be borrowed as the tap /ɾ/ as in baromaʃi 'dove' from Spanish 'paloma'. The Spanish voiceless stops /p, t, k/ are usually borrowed as their voiced counterparts as in bádú 'duck' from Spanish pato 'duck'. Loanwords from Spanish with stress on the first syllable are usually borrowed with high tone on all syllables as in: sábáná 'blanket' from Spanish sábana 'bedsheet'. Nahuatl loanwords include ndɛ̌nt͡su 'goat' from Nahuatl teːnt͡soneʔ 'goat' (literally "beard possessor"), and different forms for the Nahuatl word for 'pig', pitso:tɬ. Both of these loans have obviously entered Otomi in the colonial period after the Spanish introduced those domestic animals.[39] In the period before Spanish contact it appears that borrowing between Nahuatl and Otomi was sparse whereas there are numerous instances of loan translations from that period, probably due to widespread bilingualism.[78]

Poetry

Among the Aztecs the Otomi were well known for their songs, and a specific genre of Nahuatl songs called otoncuicatl "Otomi Song" are believed to be translations or reinterpretations of songs originally composed in Otomi.[79][80] None of the songs written in Otomi during the colonial period have survived; however, beginning in the early 20th century, anthropologists have collected songs performed by modern Otomi singers. Anthropologists Roberto Weitlaner and Jacques Soustelle collected Otomi songs during the 1930s, and a study of Otomi musical styles was conducted by Vicente T. Mendoza.[81] Mendoza found two distinct musical traditions: a religious, and a profane. The religious tradition of songs, with Spanish lyrics, dates to the 16th century, when missionaries such as Pedro de Gante taught Indians how to construct European style instruments to be used for singing hymns. The profane tradition, with Otomi lyrics, possibly dates to pre-Columbian times, and consists of lullabies, joking songs, songs of romance or ballads, and songs involving animals. As in the traditions of other Mesoamerican languages, a common poetic instrument is the use of parallelism, couplets, difrasismos (Mesoamerican couplet metaphors, similar to kennings) and repetition.[82] In the 21st century a number of Otomi literary works have been published, including the work ra hua ra hiä by Adela Calva Reyes. The following example of an Otomi song about the brevity of life was recollected by Ángel María Garibay K. in the mid-twentieth century:[cn 18]

|

|

Notes

- 1 2 Palancar (2009:14): "Desde un punto de vista de la tipología morfológica clásica greenbergiana el otomí es una lengua fusional que se convertiría, por otro lado en aglutinante si todos los clíticos se reanalizaran como afijos (From the point of view of the classic Greenbergian morphological typologogy, Otomí is a fusional language which would however turn into an agglutinating one if all the clitics were reanalyzed as affixes)"

- ↑ See the individual articles for the forms used in each dialect.

- ↑ In most modern varieties of Otomi the name for "Mexico" has changed to ʔmôndo (in Ixtenco Otomi) or ʔmóndá (in Mezquital Otomi). In some varieties of Highland Otomi it is mbôndo. Only Tilapa Otomi and Acazulco Otomi preserve the original pronunciation (Lastra, 2006:47).

- ↑ The Huichapan Codex is reproduced and translated in Ecker (2001).

- ↑ Percentages given are in comparison to the total Otomi speaking population.

- ↑ Adopted at a world linguistics conference in Barcelona, it "became a general reference point for the evolution and discussion of linguistic rights in Mexico" Pellicer, Cifuentes & Herrera (2006:132)

- ↑ 33.5% of Otomi speakers are illiterate compared with national average of 8.5% INEGI (2009:74)

- ↑ "A linguistic variety is defined as ‘a variety of speech (i) which has structural and lexical differences in comparison with other varieties within the same linguistic group, and (ii) which has a distinct sociolinguistic mark of identity for their users, different from the sociolinguistic identity born by speakers of other varieties'"(translation by E. Palancar in Palancar (2011:247). Originaltext in CLIN (2008:37)

- ↑ The classification follows Lastra except in regard to the Amealco dialect which follows Palancar (2009)

- ↑ The phonology as described by Palancar (2009:2). The Tultepec dialect is chosen here because it is the dialect for which the most complete phonological description is available. Other descriptions exist for Temoaya Otomi Andrews (1949), and several different analyses of Mezquital phonology Wallis (1968), Bernard (1973), Bernard (1967), Bartholomew (1968).

- ↑ In the late 20th century, Mezquital Otomi was reported to be on the verge of losing the distinction between nasal and oral vowels. Bernard noted that *ɑ̃ had become /ɔ/, that /ĩ ~ i/ and /ũ ~ u/ were in free variation, and that the only nasal vowel that continued to be distinct from its oral counterpart was /ẽ/.Bernard (1967)Bernard (1970)

- ↑ During the mid-twentieth century, linguists differed regarding the analysis of tones in Otomi. Kenneth Pike Sinclair & Pike (1948), Doris Bartholomew Bartholomew (1968);Bartholomew (1979) and Blight & Pike (1976) preferred an analysis including three tones, but Leon & Swadesh (1949)and Bernard (1966), Bernard (1974) preferred an analysis with only two tones, in which the rising tone was analyzed as two consecutive tones on one long vowel. In fact, Bernard didn't believe that Otomi should be analyzed as being tonal, as he believed instead that tone in Otomi was not lexical, but rather predictable from other phonetic elements. This analysis was rejected as untenable by the thorough analysis of Wallis (1968) and the three tone analysis became the standard.

- ↑ The ILV is the affiliate body of SIL International in Mexico.

- ↑ The table below is based on data from Lastra (2006: 43–62).

- ↑ Here tʔɛɡí means 'bell'.

- ↑ Borrowed from colonial Spanish tomín 'silver coin used in parts of colonial Spanish America'.

- ↑ Other highland dialects use mbɛhti (Tutotepec, Hidalgo) and menyu (Hueytlalpan).

- ↑ Originally published in Garibay (1971:238), republished in phonemic transcription in Lastra (2006:69–70)

Citations

- ↑ Lenguas indígenas y hablantes de 3 años y más, 2020 INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020.

- 1 2 3 INEGI (2009:69)

- 1 2 3 Lastra (2006:56–58)

- 1 2 Wright Carr (2005a)

- 1 2 3 Hekking & Bakker (2007:436)

- ↑ Palancar (2008:357)

- 1 2 Lastra (2006:33)

- 1 2 Wright Carr (2005b)

- ↑ Lastra 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ Lastra 2006, p. 132.

- ↑ Lastra 2006, pp. 143–146.

- ↑ Cárceres 1907.

- ↑ Lope Blanch 2004, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lastra (2006:37–41)

- ↑ Zimmermann (2012)

- ↑ Neve y Molina 2005.

- ↑ cf. in general Zimmermann 1997

- 1 2 Suárez (1983:167)

- ↑ Pellicer, Cifuentes & Herrera 2006, pp. 132–137.

- ↑ INALI [Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas] (n.d.). "Presentación de la Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos". Difusión de INALI (in Spanish). INALI, Secretaría de Educación Pública. Archived from the original on 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Lastra (2001:19–25)

- ↑ "INEGI: Cada vez más mexicanos hablan una lengua indígena - Nacional - CNNMéxico.com". Mexico.cnn.com. 2011-03-30. Archived from the original on 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ↑ Lastra 2000.

- ↑ INEGI 2009, p. 70.

- ↑ Suárez 1983, p. 168.

- ↑ Lastra 2006, pp. 32–36.

- ↑ Campbell 2000.

- ↑ Otomi in Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2022). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (25th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- 1 2 3 Palancar 2011.

- ↑ Lastra 2001.

- ↑ Lastra 2006.

- 1 2 3 Lastra (2006:57); Wright Carr (2005a)

- 1 2 Lastra (2006:58)

- 1 2 3 4 Lastra (2006:57)

- ↑ Newman & Weitlaner 1950a.

- ↑ Newman & Weitlaner 1950b.

- ↑ Bartholomew 1960.

- 1 2 Lastra (2006:48)

- 1 2 Lastra (1998b)

- 1 2 3 4 Hekking & Bakker 2007.

- 1 2 Voigtlander & Echegoyen (1985)

- ↑ Bartholomew (1979)

- ↑ Blight & Pike 1976.

- 1 2 Smith-Stark (2005:32)

- ↑ Smith-Stark 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Bartholomew (1968)

- ↑ Bernard & Salinas Pedraza 1976.

- ↑ Salinas Pedraza 1978.

- ↑ Chávez & Lanier Murray 2001.

- 1 2 Palancar 2009.

- ↑ Palancar 2009, p. 64.

- ↑ Soustelle 1993, p. 143-5.

- ↑ Andrews 1993.

- ↑ Hekking 1995.

- ↑ Lastra (2006:54–55)

- ↑ Lastra 1997.

- ↑ Lastra 1998b.

- 1 2 Lastra (1992:18–19)

- ↑ Lastra 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Wallis (1964)

- ↑ Voigtlander & Echegoyen 1985.

- ↑ Palancar 2004b.

- ↑ Palancar 2006a.

- ↑ Palancar 2006b, p. 332.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Palancar (2008)

- 1 2 Lastra (1996:3)

- ↑ Lastra 1998a.

- 1 2 Lastra (1992:24)

- ↑ Lastra 1992, pp. 226–225.

- ↑ Lastra 1992, p. 34.

- ↑ Lastra 1992, p. 20.

- ↑ Palancar 2006b.

- ↑ Lastra 1992, p. 21.

- ↑ Lastra 1992, p. 56.

- ↑ Palancar 2008, p. 358.

- ↑ Hess 1968, pp. 79, 84–85.

- ↑ Hekking & Bakker 2007, p. 439.

- ↑ Wright Carr 2005b.

- ↑ Lastra 2006, p. 69.

- ↑ Garibay 1971, p. 231.

- ↑ Lastra 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Bartholomew 1995.

References

- Andrews, Henrietta (October 1949). "Phonemes and Morphophonemes of Temoayan Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 15 (4): 213–222. doi:10.1086/464047. JSTOR 1263147. S2CID 143776150.

- Andrews, Henrietta (1993). The Function of Verb Prefixes in Southwestern Otomí. Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington publications in linguistics. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics. ISBN 978-0-88312-605-9.

- Bartholomew, Doris (October 1960). "Some revisions of Proto-Otomi consonants". International Journal of American Linguistics. 26 (4): 317–329. doi:10.1086/464591. JSTOR 1263552. S2CID 144874022.

- Bartholomew, Doris (July 1968). "Concerning the Elimination of Nasalized Vowels in Mezquital Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 34 (3): 215–217. doi:10.1086/465017. JSTOR 1263568. S2CID 143848950.

- Bartholomew, Doris (January 1979). "Otomi Parables, Folktales, and Jokes [Book review]". International Journal of American Linguistics. 45 (1): 94–97. doi:10.1086/465579. JSTOR 1264981.

- Bartholomew, Doris (1995). "Difrasismo en la narración otomi". In Ramón Arzápalo; Yolanda Lastra de Suárez (eds.). Vitalidad e influencia de las lenguas indígenas en Latinoamérica. Segundo Coloquio Mauricio Swadesh. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. pp. 449–464. ISBN 978-968-36-3312-5.

- Bernard, H Russell (December 1966). "Otomi Tones". Anthropological Linguistics. 8 (9): 15–19. JSTOR 30029194.

- Bernard, H Russell (July 1967). "The Vowels of Mezquital Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 33 (3): 247–48. doi:10.1086/464969. JSTOR 1264219. S2CID 143569805.

- Bernard, H Russell (January 1970). "More on Nasalized Vowels and Morphophonemics in Mezquital Otomi: A Rejoinder to Bartholomew". International Journal of American Linguistics. 36 (1): 60–63. doi:10.1086/465093. JSTOR 1264486. S2CID 143548278.

- Bernard, H. Russell (July 1973). "Otomi Phonology and Orthography". International Journal of American Linguistics. 39 (3): 180–184. doi:10.1086/465262. JSTOR 1264569. S2CID 143961988.

- Bernard, H Russell (April 1974). "Otomi Tones in Discourse". International Journal of American Linguistics. 40 (2): 141–150. doi:10.1086/465300. JSTOR 1264352. S2CID 144848859.

- Bernard, H. Russel; Salinas Pedraza, Jesús (1976). Otomí Parables, Folk Tales and Jokes. Native American Text Series. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISSN 0361-3399.

- Bernard, H Russell (April 1980). "Orthography for Whom?". International Journal of American Linguistics. 46 (2): 133–136. doi:10.1086/465642. JSTOR 1265019. S2CID 144793780.

- Blight, Richard C.; Pike, Eunice V. (January 1976). "The Phonology of Tenango Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 42 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1086/465386. JSTOR 1264808. S2CID 144527966.

- Campbell, Lyle (2000) [1997]. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics (OUP pbk ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509427-5.

- Cárceres, Pedro de (1907) [ca. 1550–1600]. Nicolás León (ed.). "Arte de la lengua othomí". Boletín del Instituto Bibliográfico Mexicano. 6: 39–155.

- Chávez, Evaristo Bernabé; Lanier Murray, Nancy (2001). "Notas históricas sobre las variaciones de los alfabetos otomíes" (PDF). Publicaciones impresas. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- CLIN, Catalogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales, 2008 (2008). Variantes Lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas (PDF). Mexico City.: Diario de la Nación (14 Jan.).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Lastra, Yolanda; Bartholomew, Doris, eds. (2001). Códice de Huichapan: paleografía y traducción. (in Otomi and Spanish). Translated by Ecker, Lawrence. México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-9005-0.

- Egland, Steven; Bartholomew, Doris; Cruz Ramos, Saúl (1983). La inteligibilidad interdialectal en México: Resultados de algunos sondeos. México, D.F: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Garibay, Ángel María (1971). "Poemas otomíes". Historia de la literature náhuatl. Primera parte: Etapa autonoma: de c. 1430 a 1521. Bibliotheca Porrúa (2nd ed.). Mexico: Hnos. Porrúa. pp. 231–273.

- Hekking, Ewald (1995). El Otomí de Santiago Mexquititlan: desplazamiento linguïstico, préstamos y cambios grammaticales. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

- Hekking, Ewald; Bakker, Dik (2007). "The Case of Otomí: A contribution to grammatical borrowing in crosslinguistic perspective". In Yaron Matras; Jeanette Sakel (eds.). Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 435–464. doi:10.1515/9783110199192.435. ISBN 978-3-11-019628-3.

- Hernández Cruz, Luis; Victoria Torquemada, Moisés; Sinclair Crawford, Donaldo (2004). Diccionario del hñähñu (otomí) del Valle del Mezquital, estado de Hidalgo (PDF). Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas "Mariano Silva y Aceves" (in Spanish). Tlalpan, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. ISBN 978-968-31-0313-0.

- Hess, H. Harwood (1968). The Syntactic Structure of Mezquital Otomi. Janua Linguarum. Series practica. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 9783112026465. OCLC 438991.

- INEGI, [Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografia] (2009). Perfil sociodemográfico de la población que habla lengua indígena (PDF) (in Spanish). INEGI. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- Lastra, Yolanda (1992). El Otomí de Toluca. (in Otomi and Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-2260-0.

- Lastra, Yolanda (1996). "Verbal Morphology of Ixtenco Otomi" (PDF). Amérindia. 21: 93–100. ISSN 0221-8852. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2009-08-05. (PDF has a different pagination from the original publication)

- Lastra, Yolanda (1997). El Otomí de Ixtenco. (in Otomi and Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-6000-8.

- Lastra, Yolanda (1998a). Ixtenco Otomí. Languages of the world/Materials series. München: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-929075-15-1.

- Lastra, Yolanda (1998b). "Otomí loans and creations". In Jane H. Hill; P. J. Mistry; Lyle Campbell (eds.). The Life of Language: Papers in Linguistics in Honor of William Bright. Trends in linguistics series. Studies and Monographs. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 59–101. ISBN 978-3-11-015633-1.

- Lastra, Yolanda (2000). "Otomí language shift and some recent efforts to reverse it". In Joshua Fishman (ed.). Can threatened languages be saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-492-2.

- Lastra, Yolanda (2001). Unidad y diversidad de la lengua. Relatos otomíes (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-9509-3.

- Lastra, Yolanda (2006). Los Otomies – Su lengua y su historia (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-970-32-3388-5.

- Leon, Frances; Swadesh, Morris (1949). "Two views of Otomi prosody". International Journal of American Linguistics. 15 (2): 100–105. doi:10.1086/464028. JSTOR 1262769. S2CID 144006207.

- Lope Blanch, Juan M. (2004). Cuestiones de filología mexicana. Publicaciones del Centro de Lingüística Hispánica (in Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-970-32-0976-7.

- Neve y Molina, Luis de (2005) [1767]. Erik Boot (ed.). Reglas de Orthographia, Diccionario, y Arte del Idioma Othomi (PDF) (in Spanish). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- Newman, Stanley; Weitlaner, Roberto (1950a). "Central Otomian I:Proto-Otomian reconstructions". International Journal of American Linguistics. 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/464056. JSTOR 1262748. S2CID 144486505.

- Newman, Stanley; Weitlaner, Roberto (1950b). "Central Otomian II:Primitive central otomian reconstructions". International Journal of American Linguistics. 16 (2): 73–81. doi:10.1086/464067. JSTOR 1262851. S2CID 143618683.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2004a). "Datividad en Otomi". Estudios de Cultura Otopame. 4: 171–196.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2004b). "Verbal Morphology and Prosody in Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 70 (3): 251–78. doi:10.1086/425601. JSTOR 3652030. S2CID 143924185.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2006a). "Intransitivity and the origins of middle voice in Otomi". Linguistics. 44 (3): 613–643. doi:10.1515/LING.2006.020. S2CID 144073740.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2006b). "Property in Otomi: a language with no adjectives". International Journal of American Linguistics. 72 (3): 325–66. doi:10.1086/509489. S2CID 144634622.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2008). "Emergence of Active/Stative alignment in Otomi". In Mark Donohue; Søren Wichmann (eds.). The Typology of Semantic Alignment. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923838-5.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2009). Gramática y textos del hñöñhö Otomí de San Ildefonso Tultepec, Querétaro. Vol 1. Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro: Plaza y Valdés. ISBN 978-607-402-146-2.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2011). "The conjugations of Colonial Otomi". Transactions of the Philological Society. 109 (3): 246–264. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968x.2011.01275.x.

- Pellicer, Dora; Cifuentes, Bábara; Herrera, Carmen (2006). "Legislating diversity in twenty-first century Mexico". In Margarita G. Hidalgo (ed.). Mexican Indigenous Languages at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century. Contributions to the Sociology of Language. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 127–168. ISBN 978-3-11-018597-3.

- Salinas Pedraza, Jesús (1978). Rc Hnychnyu = The Otomí. Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0484-1.

- Sinclair, Donald; Pike, Kenneth (1948). "Tonemes of Mesquital Otomi". International Journal of American Linguistics. 14 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1086/463988. JSTOR 1263233. S2CID 143650900.

- Smith-Stark, Thomas (2005). "Phonological Description in New Spain". In Otto Zwartjes; Maria Cristina Salles Altman (eds.). Missionary Linguistics II = Lingüística misionera II: Orthography and Phonology. Second International Conference on Missionary Linguistics, São Paulo, 10–13 March 2004. Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science. Series III: Studies in the history of the language sciences. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 3–64. ISBN 978-90-272-4600-4.

- Soustelle, Jacques (1993) [1937]. La familia Otomí-Pame del México central. Sección de Obras de Historia (in Spanish). Nilda Mercado Baigorria (trans.) (Translation of: "La famille Otomí-Pame du Mexique central", doctoral thesis ed.). México, D.F.: Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 978-968-16-4116-0.

- Suárez, Jorge A. (1983). The Mesoamerian Indian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22834-3.

- Voigtlander, Katherine; Echegoyen, Artemisa (1985) [1979]. Luces Contemporaneas del Otomi: Grámatica del Otomi de la Sierra. Serie gramáticas de lenguas indígenas de México (in Spanish). Mexico, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. ISBN 978-968-31-0045-0.

- Wallis, Ethel E. (1964). "Mezquital Otomi Verb Fusion". Language. Language, Vol. 40, No. 1. 40 (1): 75–82. doi:10.2307/411926. JSTOR 411926.

- Wallis, Ethel E. (1968). "The Word and the Phonological Hierarchy of Mezquital Otomi". Language. Language, Vol. 44, No. 1. 44 (1): 76–90. doi:10.2307/411465. JSTOR 411465.

- Wright Carr, David Charles (2005a). "Precisiones sobre el término "otomí"" (PDF). Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). 13 (73): 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2008. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- Wright Carr, David Charles (2005b). "Lengua, cultura e historia de los otomíes". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). 13 (73): 26–2. Archived from the original on 2011-02-26.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (1997). "La descripción del otomí/hñahñu en la época colonial: lucha y éxito". In Zimmermann, Klaus (ed.). La descripción de las lenguas amerindias en la época colonial. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert/Madrid: Iberoamericana 1997. pp. 113–132.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2012). "El autor anónimo de 'Luces del otomí' (manuscrito del siglo XVIII): ¿El primer historiógrafo de la lingüística misionera?". In Alfaro Lagorio Consuelo; Rosa, Maria Carlota; Freire, José Ribamar Bessa (eds.). Políticas de línguas no Novo Mundo. Rio de Janeiro: Editora da UERJ. pp. 13–39.

- "Estadística básica de la población hablante de lenguas indígenas nacionales 2015". site.inali.gob.mx. Retrieved 2019-10-26.</ref>

Further reading

- Bartholomew, Doris (1963). "El limosnero y otros cuentos en otomí". Tlalocan (in Spanish). 4 (2): 120–124. doi:10.19130/iifl.tlalocan.1963.315. ISSN 0185-0989.

- Hensey, Fritz G. (1972). "Otomi Phonology and Spelling Reform with Reference to Learning Problems". International Journal of American Linguistics. 38 (2): 93–95. doi:10.1086/465191. JSTOR 1265043. S2CID 144890785.

- Lastra, Yolanda (1989). Otomi de San Andrés Cuexcontitlan, Estado de México (PDF). Archivo de Lenguas Indígenas de México (in Spanish). México D.F.: El Colegio de México. ISBN 978-968-12-0411-2.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2007). "Cutting and breaking verbs in Otomi: An example of lexical specification". Cognitive Linguistics. 18 (2): 307–317. doi:10.1515/COG.2007.018. S2CID 145122834.

- Palancar, Enrique L. (2008). "Juxtaposed Adjunct Clauses in Otomi: Expressing Both Depictive and Adverbial Semantics". International Journal of American Linguistics. 74 (3): 365–392. doi:10.1086/590086. S2CID 144994029.

- Wallis, Ethel E. (1956). "Simulfixation in Aspect Markers of Mezquital Otomi". Language. 32 (3): 453–59. doi:10.2307/410566. JSTOR 410566.

External links

- Otomi Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- Comparative Otomi Swadesh vocabulary list (from Wiktionary)

- ELAR archive of Otomi language documentation materials