_Gun_on_Moncrieff_disappearing_mount%252C_at_Scaur_Hill_Fort%252C_Bermuda.jpg.webp)

A disappearing gun, a gun mounted on a disappearing carriage, is an obsolete type of artillery which enabled a gun to hide from direct fire and observation. The overwhelming majority of carriage designs enabled the gun to rotate backwards and down behind a parapet, or into a pit protected by a wall, after it was fired; a small number were simply barbette mounts on a retractable platform. Either way, retraction lowered the gun from view and direct fire by the enemy while it was being reloaded. It also made reloading easier, since it lowered the breech to a level just above the loading platform, and shells could be rolled right up to the open breech for loading and ramming. Other benefits over non-disappearing types were a higher rate of repetitive fire and less fatigue for the gun crew.[1]

Some disappearing carriages were complicated mechanisms, protection from aircraft observation and attack was difficult, and almost all restricted the elevation of the gun. With a few exceptions, construction of new disappearing gun installations ceased by 1918. The last new disappearing gun installation was a solo 16-inch gun M1919 at Fort Michie on Great Gull Island, New York, completed in 1923. In the U.S., due to lack of funding for sufficient replacements, the disappearing gun remained the most numerous type of coast defense weapon until replaced by improved weapons in World War II.[2][3]

Although some early designs were intended as field siege guns, over time the design became associated with fixed fortifications, most of which were coastal artillery. A late exception was the use in mountain fortifications in Switzerland, where six 120mm guns on rail-mounted Saint Chamond disappearing carriages remained at Fort de Dailly until replaced in 1940.

The disappearing gun was usually moved down behind the parapet or into its protective housing by the force of its own recoil, but some also used compressed air[4] while a few were built to be raised by steam.[5]

History

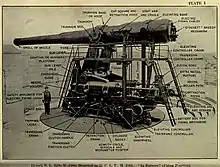

Captain (later Colonel Sir) Alexander Moncrieff[6] improved on existing designs for a gun carriage capable of rising over a parapet before being reloaded from behind cover. His design, based on his observations in the Crimean War was the first widely adopted, used in many forts of the British Empire. The first experimental carriages of this type were wheeled.[7] His key innovation was a practical counterweight system that raised the gun as well as controlled the recoil. Moncrieff promoted his system as an inexpensive and quickly constructed alternative to a more traditional gun emplacement.[8]

The usefulness of such a system had been noted earlier, and experimental designs with raisable platforms or eccentric wheels, with built-in counterweights, were built or proposed. Some used paired guns, in which one cannon acted as the other's counterweight, or counterpoise. An unsuccessful attempt at a disappearing carriage was King's Depression Carriage, designed by William Rice King of the United States Army Corps of Engineers in the late 1860s. This used a counterweight to allow a 15-inch (381 mm) Rodman gun to be moved up and down a swiveling ramp, so the weapon could be reloaded, elevated, and traversed behind cover. The carriage was subjected to six trials in 1869–1873. It was not adopted; an 1881 letter to the Chief of Engineers by Lt. Col. Quincy A. Gillmore stated that it "still leaves a great deal of heavy work to the slow and uncertain process of manual labor".[9] Part of a test installation at Fort Foote, Maryland remains.[10] King's design was better suited for breech-loaders; had the US not had a plethora of new muzzle-loaders just after the Civil War it may have seen wider use.[9]

Buffington and Crozier further refined the concept in the late 1880s by allowing the counterweight fulcrum to slide, giving the gun a more elliptical recoil path. The Buffington–Crozier Disappearing Carriage (1893) represented the zenith of disappearing gun carriages,[11] and guns of up to 16-inch size were eventually mounted on such carriages. Disappearing guns were highly popular for a while in the British Empire, the United States and other countries. In the United States, they were the primary armament of the Endicott- and Taft-era fortifications, constructed 1898–1917. Simpler carriages with a limited disappearing function were initially provided for smaller weapons, the balanced pillar for the 5-inch gun M1897 and the Driggs-Seabury masking parapet for the manufacturer's 3-inch gun M1898. However, these could only be retracted at a specific traverse angle (90° off the emplacement's axis), thus could not be used in action. Due to the mount's undesired flexibility when fired interfering with aiming, both types were disabled beginning in 1913 in the "up" position,[12] with installations circa 1903 and later having received pedestal mounts. Both carriage types and their associated guns were removed from service in the 1920s; in the 3-inch gun's case a tendency for the piston rod to break was a factor in their removal.[13]

Several mobile disappearing mounts appeared in France and Germany circa 1893. These included both road-mobile and rail-mobile designs. In France, Schneider and St. Chamond produced road-mobile design and rail-mobile designs, in 120 mm (4.7 inch) and 155 mm weapons. The 0.6 meter rail affût-truck system was used tactically for 120mm and 155mm guns in WWI. Six 120 mm Modèle 1882 guns on St. Chamond mounts were deployed at Fort de Dailly in Switzerland from 1894 to 1939.[14][15] Krupp produced a rail-mobile 120 mm disappearing gun in 1900.[16]

Though effective against ships, the guns were vulnerable to aerial observation and attack. After World War I coastal guns were usually casemated for protection or covered with camouflage for concealment.[17] By 1912, disappearing guns were declared obsolete in the British Army, with only a few other countries, particularly the United States, still producing them up to World War I[4] and retaining them in service until replaced by casemated batteries in World War II.[3][11]

The only major campaign in which US disappearing guns played a part was the Japanese invasion of the Philippines, which began shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and ended with the surrender of US forces on 6 May 1942. The disappearing guns were the least useful of the coast defense assets, as they were positioned to defend against warships entering Manila Bay and Subic Bay and in most cases could not engage Japanese forces due to limited traverse. Despite attempts at camouflage, their emplacements were vulnerable to air and high-angle artillery attack.

Advantages

The disappearing carriage had several principal advantages:

- It afforded the gun crew protection from direct fire by raising the gun over the parapet (or wall in front of the gun) only when it was to be fired, otherwise leaving it at a lower level, where it was also able to be loaded easily.

- With its guns in a retracted position (down behind the parapet), the battery was much harder to spot from the sea, making it a much harder target for attacking ships. Flat trajectory fire tended simply to fly over the battery, without damaging it.

- Interposing of a moving fulcrum between the gun and its platform lessened the strain on the latter and allowed it to be of lighter construction while limiting recoil travel.

- Simple, well protected earthen and masonry gun pits were much more economical to construct than the previous practice of constructing the standing heavy walls and fortified casemates of a more traditional gun emplacement.

- The entire battery could be hidden from view in place when not in use, unlike a traditional fort, enabling ambuscade fire.

- Higher rate of repetitive fire over non-disappearing types.[1]

- Less fatigue for the gun crew.[1]

Disadvantages

The disappearing gun had several drawbacks as well:

- Some British carriage designs restricted maximum elevation to under 20 degrees and thus lacked the necessary range to match newer naval guns entering service during the early part of the 20th century.[11] (Buffington-Crozier carriages, at their final development, could manage 30 degrees on a 16-inch gun.[18]) The additional elevation gained by mounting the same gun on a later non-disappearing carriage increased its range.[19]

- The time taken for the gun to swing up and down and be reloaded slowed the rate of fire of some designs. Surviving records indicate a rate of fire of one round per one to two minutes for a British eight-inch (20 cm) gun, significantly slower than less complicated guns.[4] (By contrast, the Buffington-Crozier 16-inch mount could manage one round per minute; the barbette mount was only 20 percent faster, and was slower at some elevations.)

- The improvement in the speed of warships demanded an increased rate of firing. The disappearing gun was at a disadvantage compared with a gun that stayed in position as one could not aim or reposition a disappearing gun while it was in the lowered position. The gunner still had to climb atop the weapon via an elevated platform to sight and lay the weapon after it was returned to firing position,[11] or receive fire control information (range and bearing) transmitted from a remote location.

- Their relative size and complexity also made them expensive compared with non-disappearing mounts,[4] In 1918, the 12" DC gun cost $102,000, the barbette mounted gun $92,000.[20] This was more than made up, for some designs, by the reduced cost of protection. From the above reference, the cost of a 16" DC emplacement was $605,000, while a turreted gun's proportional cost was $2,050,000.

Other applications

Gun lift battery

One very uncommon and even more complex type of disappearing gun was Battery Potter at Fort Hancock in the Coast Defenses of Sandy Hook, New Jersey. This and a number of 12-inch barbette emplacements were constructed due to the inability of the early versions of the Buffington-Crozier carriage to accommodate a 12-inch gun. Built in 1892, the battery covered the approaches to New York harbor. Instead of using recoil from the gun to lower the weapon, two 12-inch barbette carriages were placed on individual hydraulic elevators that would raise the 110-ton carriage and gun 14 feet to enable it fire over a parapet wall. After firing, the gun was lowered for reloading using hydraulic ramrods and a shell hoist. While the operation of the battery was slow, taking 3 minutes per shot, its design allowed a 360° field of fire. Since its design was not further pursued, Battery Potter was disarmed in 1907.[21]

Battery Potter required much machinery to operate the gun lifts, including boilers, steam-powered hydraulic pumps, and two accumulators. Due to the inability to generate steam quickly, Battery Potter's boilers were run nonstop during its 14-year life, at significant cost. After the proving of the Buffington-Crozier carriage for 12-inch guns, the United States Army abandoned plans to build several additional gun lift batteries.

Naval artillery

The concept was also attempted for conversion to a naval use. HMS Temeraire was completed in 1877 with two disappearing guns (11-inch (279 mm) muzzle-loading rifles on Moncrieff-type carriages) sinking down into barbette structures (basically circular metal protective walls over which the gun fired when elevated). This was to combine the ability of the early pivot guns to swivel with the protection of more classical fixed naval guns.[22] A similar design was later used in Russia for the first ship of the Ekaterina II-class battleships and also used in the monitor Vitse-admiral Popov. It has been suggested that both the harsh saltwater environment and the constant swaying and rolling of a ship at sea caused problems for the complex mechanism.[11]

If the mechanism seemed too temperamental for the open sea, it was not true for rivers and harbors. Armstrong and Mitchell's 1867 HMS Staunch, a gunboat described as a "floating gun carriage", used a single 9-inch (229 mm) Armstrong rifled muzzle loader on a lowering platform with next to no armor. It was a resounding commercial success; there were 21 direct copies,[23] and another six near-sisters,[24] plus six near-copies (see List of gunboat and gunvessel classes of the Royal Navy). Known as the "flatiron" gunboats, these vessels had a single large gun kept behind hinged shields, rather than a complex disappearing mount.[25] The simplified mounts were intended as much to lower the center of mass as to afford protection, and resembled a "lift battery." The gun was not normally lowered between shots.

Related and parallel systems

U.S. Endicott-era balanced pillar and masking parapet mounts were, in a sense, a hybrid of simple pedestal mounts and disappearing mounts: the guns were hidden from observation while out of action, but, once engaged, remained vulnerable to direct observation and direct fire. The emplacement designs only permitted retraction with the gun barrel at a specific traverse angle, usually 90° off the emplacement's axis. Since the barrels substantially overlapped the parapet of their installation, it was impossible to point the piece while concealed. The balanced pillar mount was used primarily with the 5-inch gun M1897, while the masking parapet mount was a Driggs-Seabury patent used primarily with the manufacturer's 3-inch gun M1898. "Masking parapet" was a proprietary term coined by Driggs-Seabury to distinguish their carriage from balanced pillar designs. Beginning in 1913 these carriages were disabled in the "up" position due to undesired flexibility interfering with aiming. The M1898 3-inch gun also developed a tendency for the piston rod to break when fired, and both types and their associated guns were removed from service in the 1920s.[12][13]

In 1893 Germany's Hermann Gruson developed an armored turret for a 53 mm gun called a "Fahrpanzer" (mobile armor) that had both road- and rail-mobile versions. These were sold to several other countries prior to World War I, notably Switzerland, Romania, and Greece, were widely deployed in that war, and were present in most major Swiss fortifications at least through World War II, including Fort Airolo.[26][27] Surviving examples of the Fahrpanzer are at the Athens War Museum and the Brussels Army Museum. These mounts were intended for use in prepared trench-type positions that would shelter them from view when retracted; in the Swiss forts they were stored in covered bunkers until repositioned to fire.[14] While a few units used in fixed fortifications were sometimes mounted on sinking platforms or on short rail stubs intended for tactical concealment, the overwhelming majority were not, and acted in action as completely fixed guns, and are outside the subject of this article.

Retractable turrets were also conceptually similar, but almost never depended on recoil actuation, and, like the balanced pillar systems, often remained visible when actually in operation. Unlike balanced pillar designs, the pieces could generally be pointed and trained from cover, allowing complete surprise for the first shot. They were extensively developed for Continental European land defenses, but little used elsewhere.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers". 54 part A. American Society of Civil Engineers. 1905: 66.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Complete list of US forts and batteries at CDSG website

- 1 2 Berhow, pp. 200-228

- 1 2 3 4 Disappearing Guns Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine (from the Royal New Zealand Artillery Old Comrades Association)

- ↑ The Defenses of Sandy Hook Archived 2009-06-17 at the Wayback Machine (from a Sandy Hook, Gateway National Recreation Area, U.S. National Park Service information pamphlet. Accessed 2008-02-22.)

- ↑ Seton, George (1890). The House Of Moncrieff (PDF). Edinburgh. pp. 136–138.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hydro-pneumatic carriages at Victorian Forts and Artillery

- ↑ "Moncrieff's method of mounting guns with counterweights, of using them in gun-pits, and of laying them with reflecting sights : a paper read at the Royal United Service Institution (1866)" (from archive.org. Accessed 2009-06-25.)

- 1 2 Smith, Bolling W. (Winter 2020). "William Rice King and His Counterpoise Carriage". Coast Defense Journal. Vol. 34, no. 1. Mclean, Virginia: CDSG Press.

- ↑ King's Depression Carriage at the Historical Marker Database

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Disappearing Gun (from the 'navyandmarine.org' website, with further references. Accessed 2008-02-22.)

- 1 2 Smith, Bolling W. (Fall 2019). "The Driggs-Seabury 15-pounder (3-inch) Masking-Parapet Carriage". Coast Defense Journal. Vol. 33, no. 4. Mclean, Virginia: CDSG Press. pp. 12–18.

- 1 2 Berhow, pp. 70-71, 88-89

- 1 2 "Fort de Dailly at ASMEM (Association St-Maurice d'Etudes Militaires) (in French)". Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ La Mechanique a l'Exposition de 1900, Vol. 3, No. 15, p. 87 (in French)

- ↑ Dillard, Col. James B., "Railway Artillery", Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 41, Issue 1, January 1919, p. 44

- ↑ "Fort Winfield Scott: Battery Lowell Chamberlin". California State Military Museum. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V., "Illustrated Encyclopedia of Artillery," Chartwell House, Secaucus, NJ, 1978 p74

- ↑ The Six Inch Shield Gun Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine (from a private website. Accessed 2009-02-28.)

- ↑ Fortifications Bill Congressional Hearings, 1916, p. 154

- ↑ Berhow, pp. 130-133

- ↑ Gibbons, Tony, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships, p. 89, New York: Crescent Books, 1983, ISBN 0-517-378108

- ↑ Heald, Henrietta (2013-12-03). William Armstrong: Magician of the North (1 ed.). McNidder & Grace. p. 137.

- ↑ Morgan, Zachary (2014-11-12). Legacy of the Lash: Race and Corporal Punishment in the Brazilian Navy and. Indiana University Press. p. 172.

- ↑ HMS Staunch at Royal Museums Greenwich

- ↑ Fahrpanzer at Landships.info

- ↑ Kaufmann, J. E.; Jurga, Robert M. (1999). Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Publishing. pp. 156–160. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Second ed.). CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Hogg, I.V., "The Rise and Fall of the Disappearing Carriage", Fort (Fortress Study Group), (6), 1978

- Hogg, Ian V., "Illustrated Encyclopedia of Artillery," Chartrwell, Secaucus, NJ, 1978

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

External links

- The Moncrieff Disappearing Counterweight Carriage

- The Hydropneumatic Disappearing Mounting

- BL 10-inch gun Mk III disappearing mounting diagram at Victorian Forts and Artillery website

- Sales brochure from 1895 for the Buffington-Crozier disappearing carriage Archived 2016-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Drawing and description of the balanced pillar carriage, from Ordnance and Gunnery, 1915