| River Great Ouse | |

|---|---|

The River Great Ouse after Brownshill Staunch, near Over in Cambridgeshire | |

Great Ouse catchment | |

| Location | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Counties | Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Syresham, West Northamptonshire, Northamptonshire, England |

| • coordinates | 52°05′33″N 01°05′35″W / 52.09250°N 1.09306°W |

| • elevation | 150 m (490 ft) |

| Mouth | The Wash |

• location | King's Lynn, United Kingdom |

• coordinates | 52°48′36″N 00°21′18″E / 52.81000°N 0.35500°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 230 km (143 mi) |

| Basin size | 8,380 km2 (3,240 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Denver Sluice[1] Catchment area 3430 km2 |

| • average | 15.8 m3/s (560 cu ft/s)Catchment area 3430 km2 |

The River Great Ouse (/uːz/) is a river in England, the longest of several British rivers called "Ouse". From Syresham in Northamptonshire, the Great Ouse flows through Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk to drain into the Wash and the North Sea near Kings Lynn. Authorities disagree both on the river's source and its length with one quoting 160 mi (260 km)[2] and another 143 mi (230 km).[3] Mostly flowing north and east, it is the fifth longest river in the United Kingdom. The Great Ouse has been historically important for commercial navigation, and for draining the low-lying region through which it flows; its best-known tributary is the Cam, which runs through Cambridge. Its lower course passes through drained wetlands and fens and has been extensively modified, or channelised, to relieve flooding and provide a better route for barge traffic. The unmodified river would have changed course regularly after floods.

The name Ouse is from the Celtic or pre-Celtic *Udso-s,[4] and probably means simply "water" or slow flowing river.[5] Thus the name is a pleonasm. The lower reaches of the Great Ouse are also known as "Old West River" and "the Ely Ouse", but all the river is often referred to simply as the Ouse in informal usage (the word "Great" – which originally meant simply big or, in the case of a river, long – is used to distinguish this river from several others called the Ouse).

Course

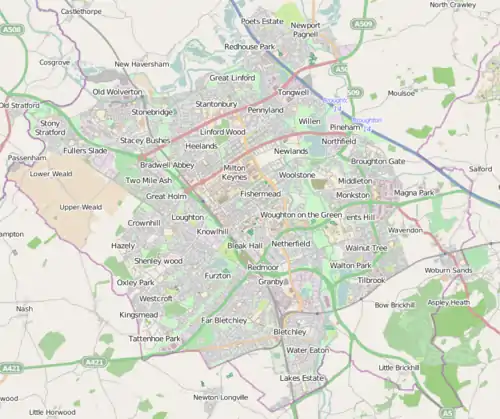

The river has several sources close to the villages of Syresham and Wappenham in South Northamptonshire. It flows through Brackley, provides the Oxfordshire/Northamptonshire border, then into Buckinghamshire where it flows through Buckingham, the Milton Keynes urban area (at Stony Stratford and Newport Pagnell) and Olney, then Kempston in Bedfordshire, which is the current head of navigation.

Passing through Bedford, it flows on into Cambridgeshire through St Neots, Godmanchester, Huntingdon, Hemingford Grey and St Ives, reaching Earith. Here, the river enters a short tidal section before branching in two. The artificial, very straight Old Bedford River and New Bedford River, which remain tidal, provide a direct link north-east towards the lower river at Denver in Norfolk.

The river previously ran through Hermitage Lock into the Old West River, then joined the Cam near Little Thetford before passing Ely and Littleport to reach the Denver sluice. Below this point, the river is tidal and continues past Downham Market to enter The Wash at King's Lynn. It is navigable from the Wash to Kempston Mill near Bedford, a distance of 72 mi (116 km) which contains 17 locks.[6] It has a catchment area of 3,240 sq mi (8,380 km2)[7] and a mean flow of 15.5 m3/s (550 cu ft/s) as measured at Denver Sluice.[8]

Its course has been modified several times, with the first recorded being in 1236, as a result of flooding. During the 1600s, the Old Bedford and New Bedford Rivers were built to provide a quicker route for the water to reach the sea. In the 20th century, construction of the Cut-Off Channel and the Great Ouse Relief Channel have further altered water flows in the region, and helped to reduce flooding.

Improvements to assist navigation began in 1618, with the construction of sluices and locks. Bedford could be reached by river from 1689. A major feature was the sluice at Denver, which failed in 1713, but was rebuilt by 1750 after the problem of flooding returned. Kings Lynn, at the mouth of the river, developed as a port, with civil engineering input from many of the great engineers of the time. With the coming of the railways the state of the river declined so that it was unsuitable either for navigation or for drainage. The navigation was declared to be derelict in the 1870s.

A repeated problem was the number of authorities responsible for different aspects of the river. The Drainage Board created in 1918 had no powers to address navigation issues, and there were six bodies responsible for the river below Denver in 1913. When the Great Ouse Catchment Board was created under the powers of the Land Drainage Act in 1930, effective action could at last be taken. There was significant sugar beet cargo traffic on the river between 1925 and 1959, with the last known commercial traffic sailing in 1974. Leisure boating had been popular since 1904, and the post-war period saw the creation of the Great Ouse Restoration Society in 1951, who campaigned for complete renovation of the river navigation. Until 1989, the river was in the care of the Anglian Water Authority until water privatisation, when the Environment Agency became the drainage and ecology authority as well as being the navigation authority.

The Ouse Washes are an internationally important area for wildlife. Sandwiched between the Old Bedford and New Bedford rivers, they consist of washland which is used as pasture during the summer but which floods in the winter, and are the largest area of such land in the United Kingdom. They act as breeding grounds for lapwings, redshanks and snipe in spring, and are home to varieties of ducks and swans during the winter months.[9]

History: drainage and navigation

River Great Ouse | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The river has been important both for drainage and for navigation for centuries, and these dual roles have not always been complementary. The course of the river has changed significantly. In prehistory, it flowed from Huntingdon straight to Wisbech and then into the sea. In several sequences, the lower reaches of the river silted, and in times of inland flood, the waters would breach neighbouring watersheds and new courses would develop – generally in a progressively eastwards fashion. In the Dark Ages, it turned to the west at Littleport, between its present junctions with the River Little Ouse and the River Lark, and made its way via Welney, Upwell and Outwell, to flow into The Wash near Wisbech. At that time it was known as the Wellstream or Old Wellenhee, and parts of that course are marked by the Old Croft River and the border between Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. After major inland flood events in the early 13th century[10] it breached another watershed near Denver and took over the channel of the old Wiggenhall Eau, and so achieved a new exit and so joined the Wash at Kings Lynn. Parts of the old course were later used for the River Lark, which flows in the reverse direction along the section below Prickwillow, after the main river was moved further to the west.[11] The original northern course began to silt up, depriving Wisbech of a reliable outlet to the sea, and was kept navigable by diverting the River Nene east to flow into it in the 1470s.

An Act of Parliament was passed in 1600 which allowed Adventurers, who paid for drainage schemes with their own money, to be repaid in land which they had drained. The Act covered large tracts of England, but no improvements were made to the region through which the Great Ouse flowed until 1618, Arnold Spencer and Thomas Girton started to improve the river between St Ives and St Neots. Six sluices were constructed, and Spencer attempted to obtain permission to improve the river to Bedford, but the Act was defeated, despite support from Bedford Corporation. Some dredging was done, and Great Barford became an inland port, but he lost a lot of money on the scheme, and the condition of the river worsened.[12]

Below Earith, thirteen Adventurers working with the Earl of Bedford formed a Corporation to drain the Bedford Levels. Cornelius Vermuyden was the engineer, and a major part of the scheme was the Old Bedford River, a straight cut to carry water from Earith to a new sluice near Salters Lode, which was completed in 1637. The sluice was not popular with those who used the river for navigation, and there were some attempts to destroy the new works during the turmoil of the English civil wars. A second drainage Act was obtained in 1649, and Vermuyden oversaw the construction of the New Bedford River, parallel to the Old Bedford River, which was completed in 1652. There was strong opposition from the ports and towns on the river, which increased as the old channel via Ely gradually silted up. Above Earith, Samuel Jemmatt took control of the river, and navigation was extended to Bedford in 1689 by the construction of new staunches and sluices.[13]

Between St Ives and Bedford, there were ten sluices, which were pound locks constructed at locations where mill weirs would have prevented navigation. There were also five staunches, which were flash locks constructed near to fords and shallows. Operation of the beam and paddle provided an extra volume of water to carry the boats over such obstructions. On the lower river, a combination of high spring tides and large volumes of floodwater resulted in the complete failure of Denver sluice in 1713. While there were celebrations among the navigators, the problem of flooding returned, and the channel below Denver deteriorated. Charles Labelye therefore designed a new sluice for the Bedford Level Corporation, which was constructed between 1748 and 1750 and included a navigation lock.[13] No tolls were charged on the river below St Ives or on the New Bedford, and those responsible for drainage complained about damage to the sluices and to banks by the horses used for towing boats. An Act of Parliament to regulate the situation was defeated in 1777 after fierce opposition, and it was not until 1789 that a Haling Act was passed, which ensured that tolls were charged and landowners were repaid for damage to the banks caused by horses. These measures were a success, as there were few complaints once the new system was in place.[14]

Port of King's Lynn

After the river had been diverted to King's Lynn, the town developed as a port. Evidence for this can still be seen, as two warehouses built in the 15th century for trade with the Hanseatic League have survived. However, the harbour and the river below Denver sluice were affected by silting, and the problem was perceived to be the effects of the sluice. Sand from The Wash was deposited by the incoming tide, and the outgoing tide did not carry it away again. Colonel John Armstrong was asked to survey the river in 1724, and suggested returning it to how it was prior to the construction of the drainage works. John Smeaton rejected this idea in 1766, suggesting that the banks should be moved inwards to create a narrower, faster-flowing channel. William Elstobb and others had suggested that the great bend in the river above King's Lynn should be removed by creating a cut, but it took 50 years of arguing before the Eau Brink Act was obtained in 1795 to authorise it, and another 26 years until the cut was finally opened in 1821. During this time, most of the major civil engineers of the time had contributed their opinions.[15] The original project head and chief engineer was Sir Thomas Hyde Page.

The work was overseen by John Rennie and Thomas Telford and construction took four years. It proved to be too narrow, resulting in further silting of the harbour, and was widened at an additional cost of £33,000 on Telford's advice. The total cost for the 2+1⁄2 mi (4.0 km) cut was nearly £500,000, and although the navigators, who had opposed the scheme, benefitted most from it, there were new problems for drainage, with the surrounding land levels dropping as the peaty soil dried out. The Eau Brink Act created Drainage Commissioners and Navigation Commissioners, who had powers over the river to St Ives, but both bodies were subject to the Bedford Levels Corporation. Although often in opposition, the two parties worked together on the construction of a new lock and staunch at Brownshill, to improve navigation above Earith.[15]

In 1835, King William IV brought a case against the Ouse Bank Commissioners regarding a mandamus writ issued in 1834 about the Eau Brink Cut and possible damages it caused to the King's Lynn harbour.[16]

The Railway Age

Denver sluice was reconstructed in 1834, after the Eau Brink Cut had been completed. Sir John Rennie designed the new structure, which incorporated a tidal lock with four sets of gates, enabling it to be used at most states of the tide. Sir Thomas Cullam, who had inherited a part share of the upper river, invested large amounts of his own money in rebuilding the locks, sluices and staunches in the 1830s and 1840s. The South Level Drainage and Navigation Act of 1827 created Commissioners who dredged the river from Hermitage Lock to Littleport bridge, and also dredged several of its tributaries. They constructed a new cut near Ely to bypass a long meander near Padnall Fen and Burnt Fen, but although the works cost £70,000, they were too late to return the navigation to prosperity. Railways arrived in the area rapidly after 1845, reaching Cambridge, Ely, Huntingdon, King's Lynn, St Ives, St Neots and Tempsford by 1850. The river below King's Lynn was improved by the construction of the 2 mi (3.2 km) Marsh Cut and the building of training walls beyond that to constrain the channel, but the railways were welcomed by the Bedford Levels Corporation, for whom navigation interfered with drainage, and by King's Lynn Corporation, who did not want to be superseded by other towns with railway interchange facilities.[17]

A large interchange dock was built at Ely, to facilitate the distribution of agricultural produce from the local region to wider markets. In addition, coal for several isolated pumping stations was transferred to boats for the final part of the journey, rather than it coming all the way from King's Lynn. Decline on most of the river was rapid, with tolls halving between 1855 and 1862. Flooding in 1875 was blamed on the poor state of the navigation, and it was recommended that it should be abandoned, but there was no funds to obtain an Act of Parliament to create a Drainage Authority. The navigation was declared to be derelict by three County Councils soon afterwards. It was then bought by the Ouse River Canal and Steam Navigation Ltd, who wanted to link Bedford to the Grand Junction Canal, but they failed to obtain their Act of Parliament. A stockbroker called L. T. Simpson bought it in 1893, and spent some £21,000 over the next four years in restoring it. He created the Ouse Transport Company, running a fleet of tugs and lighters, and then attempted to get approval for new tolls, but was opposed by Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire County Councils. Protracted legal battles followed, with Simpson nailing the lock gates together, and the County Councils declaring that the river was a public highway. The 'Godmanchester' case eventually reached the House of Lords in 1904, who allowed Simpson to close the locks.[18]

The Leisure Age

Simpson's victory in 1904 coincided with an increased use of the river for leisure. As he could not charge these boats for use of the locks, the situation was resolved for a time in 1906 by the formation of the River Ouse Locks Committee, who rented the locks between Great Barford and Bedford. Over 2000 boats were recorded using Bedford Lock in a three-month period soon afterwards. Despite pressure from local authorities and navigation companies, the upper river was closed for trade, and a Royal Commission reported in 1909 on the poor state of the lower river, the lack of any consistent authority to manage it, and the unusual practice of towing horses having to jump over fences because there were no gates where they crossed the towing path. The Ouse Drainage Board was formed in 1918, but had no powers to deal with navigation issues, and it was not until the powers of the Land Drainage Act (1930) were used to create the Great Ouse Catchment Board that effective action could be taken.[19]

The Catchment Board bought the navigation rights from Simpson's estate, and began to dredge the river and rebuild the locks. There was an upturn in commercial traffic from 1925, when the sugar beet factory at Queen Adelaide near Ely was opened. They operated six or seven tugs and a fleet of over 100 barges, and three tugs and 24 barges from the Wissington sugar beet factory on the River Wissey also operated on the river. Local commercial traffic continued around Ely until after the Second World War. The sugar beet traffic ceased in 1959, and the last commercial boat on the upper river was "Shellfen", a Dutch barge converted to carry 4,000 imp gal (18,000 L) of diesel fuel, which supplied the remote pumping stations until 1974, when the last ones were converted to electricity.[20]

Below Denver, the situation was complicated by the fact that there were six bodies with responsibility for the river in 1913. No dredging took place, as there was no overall authority. The training walls were repaired in 1930 by the King's Lynn Conservancy Board, and the Great Ouse Catchment Board reconstructed and extended them in 1937. After major flooding in 1937 and 1947, and the North Sea flood of 1953, flood control issues became more important, and the Cut-Off Channel was completed in 1964, to carry the headwaters of the River Wissey, River Lark and River Little Ouse to join the river near Denver sluice.[21] The Great Ouse Relief Channel, which runs parallel to the main river for 10+1⁄2 mi (16.9 km) from here to Wiggenhall bridge, was constructed at the same time. It joins the river at a sluice above King's Lynn, and was made navigable in 2001, when the Environment Agency constructed a lock at Denver to provide access.[22]

By 1939, the Catchment Board had reopened the locks to Godmanchester and then to Eaton Socon; in 1951 the Great Ouse Restoration Society was formed to continue the process, and successfully campaigned for and assisted with the restoration.[23] The Restoration Society campaign included the establishment of the Bedford to St. Neots Canoe Race in 1952 to publicise the case for navigational restoration. Now known as the Bedford Kayak Marathon, it is the longest established canoe race in the UK. In 1961 its organisers formalised canoeing activities on the river by forming the Viking Kayak Club.

Since 1996, the river has been the responsibility of the Environment Agency, who issue navigation licences.[24] The upper river was fully reopened to Bedford with the rebuilding of Castle Mills lock in 1978.[23]

Navigation connections

The non-tidal reaches of the river are used for leisure boating, but remain largely separated from the rest of the British inland waterway system. Several of its tributaries are navigable, including the River Cam, the River Lark, the River Little Ouse and the River Wissey. Close to Denver sluice, Salters Lode lock gives access to the Middle Level Navigations,[25] but the intervening section is tidal, and deters many boaters. Access to the Middle Level Navigations used to be possible via the Old Bedford River and Welches Dam lock, but the Environment Agency piled the entrance to the lock in 2006 and this route is no loger available for navigation. The proposed Fens Waterways Link, which aims to improve navigation from Lincoln to Cambridge may result in this section being upgraded, or a non-tidal link being created at Denver.[26]

There are two more proposed schemes to improve connections from the river to the Midlands waterway network (in addition to the Gt Ouse – Nene link via the Middle Level).

- The first is for a Bedford and Milton Keynes waterway, to connect the river to the Grand Union Canal. This idea was first proposed in 1812, when John Rennie the Elder costed a 15 mi (24 km) junction canal from Fenny Stratford to Bedford. His estimate of £180,807 scared investors, and no progress was made.[17] In 1838, there was another (failed) proposal to extend the Newport Pagnell Canal.[27] The idea was revived once more in the 1880s, when the Ouse River Canal and Steam Navigation Ltd bought the river with the aim of creating the link. An enabling Act of Parliament was defeated, although Major Marindin, acting for the Board of Trade, was optimistic about the likely benefits.[17] The modern version of the proposal is in progress since 1994, by the Bedford and Milton Keynes Waterway Trust, who have formed a partnership with 25 bodies, including local councils, British Waterways (and its successor, the Canal & River Trust) and various government agencies. A feasibility study was carried out in 2001, which looked at nine possible routes; by 2006, the cost of the preferred route was between £100 and £200 million.[27]

- The second scheme is for an extension of the Great Ouse Relief Channel to link it to the River Nar, and provide a non-tidal link to King's Lynn. The project would include a large marina, and would be part of a much larger regeneration project for the south side of the town.[26] Two locks would be required to raise boats from the Relief Channel to the River Nar.[28]

Wildlife

As the water quality has improved, otters have returned to the river in numbers such that fishing lakes now require fencing to protect stocks. Paxton Pits nature reserve near St Neots has hides from which otters are regularly seen. Coarse fishing is still popular, with a wide range of fish in the river, but it is many years since large sturgeon were caught. Seals have been recorded as far upstream as Bedford.[29][30][31] Huntingdonshire seems to be the most popular area for breeding animals in recent years. [32]

Tributaries

Tributaries of the River Great Ouse: (upstream [source] to downstream by confluence)

- Padbury Brook: Two streams that join to form one watercourse just south of Padbury in Buckinghamshire: the eastern twin starts near Addington and the Claydons and flows 5 mi (8 km) northwest to join the western twin, which starts near Somerton in Oxfordshire. From here it flows due East, through Fewcott, Stoke Lyne, Fringford and Twyford, before joining its twin and flowing 5 mi (8 km) north to join the Great Ouse east of Buckingham.[33]

- River Leck

- River Tove

- River Ouzel (or Lovat)

- River Ivel

- River Kym

- River Cam

- Soham Lode

- River Lark

- River Little Ouse

- River Wissey

- Old Bedford River

- New Bedford River (also known as Hundred Foot Drain)

- River Nar

- Gaywood River

- Babingley River

Water sports

In 1944 the annual Boat Race between the Oxford and Cambridge universities took place on this river, between Littleport and Queen Adelaide, the first time that it had not been held on the Thames; it was won by Oxford.[34] The 2021 Boat Race was again held on the river because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[35] The Great Ouse has been used by three clubs from Cambridge University for the training of rowers, with the Boat Club (CUBC),[36] the Women's Boat Club (CUWBC)[37] and the Lightweight Rowing Club (CULRC), all using facilities at Ely; the clubs merged in 2020.

The Great Ouse is a very popular river for canoeing and kayaking, particularly around Bedford which is a regional centre for the sport. Viking Kayak Club organise the Bedford Kayak Marathon with canoe racing held along the Embankment on Bedford's riverside and dates back to the original Bedford to St Neots race in 1952, believed to be the first of its kind in the country.

Bedford also benefits from the presence of weirs and sluices, creating white water opportunities. Viking organise national ranking Canoe Slalom events at the Cardington Artificial Slalom Course (CASC), which was the first artificial whitewater course in the UK, opened in 1982 adjacent to Cardington Lock, in a partnership with the Environment Agency who use it as a flood relief channel. CASC is also the venue each year for the UK's National Inter Clubs Slalom Finals, the largest canoe slalom event by participation in the UK.

Since 1978, the Bedford River Festival has been held every two years, to celebrate the link between Bedford and the coast.[38] In addition to craft often seen on the river, the 2008 festival featured a reconstruction of a 1st-century currach, consisting of a wicker framework covered in cow hide, and capable of carrying ten people.

See also

- Bedford & Milton Keynes Waterway Trust

- Bedford Rowing Club

- The Boat Race

- Cardington Artificial Slalom Course

- The Ouse Valley Way (Long-distance footpath along the Ouse)

- Rivers of the United Kingdom

- RSPB Ouse Washes (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds reserve)

- WWT Welney (Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust reserve)

- Viking Kayak Club

References

- ↑ Ely Ouse at Denver Complex Archived 28 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine gauging station.

- ↑ Clayton, Phil (2012). Headwaters: Walking to British River Sources (First ed.). London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 45. ISBN 9780711233638.

- ↑ Owen, Susan; et al. (2005). Rivers and the British Landscape. Carnegie. ISBN 978-1-85936-120-7. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ↑ Pokorny, Julius. Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. entry 9.

- ↑ Mills, Anthony David (2003). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852758-6.

- ↑ Blair 2006, p. 7

- ↑ Nedwell, D.B.; Trimmer, M.T. (1996). "Nitrogen fluxes through the upper estuary of the Great Ouse, England: the role of the bottom sediments" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. Inter Research Science. 142: 273–286. Bibcode:1996MEPS..142..273N. doi:10.3354/meps142273. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ "NRFA Station Mean Flow Data for 33035 - Ely Ouse at Denver Complex". nrfa.ceh.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ↑ "The RSPB: Ouse Washes". The RSPB. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ Register of Crabhouse Nunnery, British Library MS, and others

- ↑ Blair 2006, p. 14

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 134–137

- 1 2 Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 137–141

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 143–144

- 1 2 Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 144–146

- ↑ Adolphus & Ellis 1837, pp. 544–550

- 1 2 3 Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 146–149

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 149–151

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 151–153

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 154–156

- ↑ Jim Shead's Canal pages. "Great Ouse Relief Channel". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- 1 2 Cumberlidge 2009, p. 232

- ↑ Cumberlidge 2009, p. 233

- ↑ Cumberlidge 2009, pp. 228–229

- 1 2 Cumberlidge 2009, pp. 7–8

- 1 2 Cumberlidge 2009, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Inland Waterways Association: Kings Lynn to the Great Ouse Flood Relief Channel Link Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 10 October 2009

- ↑ "SLIDESHOW: Seal in the River Great Ouse". Bedford Times & Citizen. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Surprise guest puts seal on festival's pearl". Bedfordshire On Sunday. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Sunbathing seals make long trip inland from the Wash". BBC News. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "River great ouse flooding - river great ouse flooding".

- ↑ "Get-a-map online". Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Celebrate the 1944 University Boat Race!". BBC. February 2004. Archived from the original on 29 November 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ↑ "The Boat Race 2021 to be raced at Ely, Cambridgeshire". The Boat Race. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ↑ "CUBC: Facilities". Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ "CUWBC: Facilities". Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ "Visit Shefford, Bedford Embankment". Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

Bibliography

- Adolphus, John Leycester; Ellis, Thomas Flower (1837). Reports of cases argued and determined in the Court of King's Bench, (Volume 3, Cases from 1835, Great Britain. Court of King's Bench). London: Saunders and Benning. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Blair, Andrew Hunter (2006). The River Great Ouse and tributaries. Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85288-943-5.

- Boyes, John; Russell, Ronald (1977). The Canals of Eastern England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7415-3.

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain, 8th Ed. Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.

- Owen, Sue; et al. (2005). Rivers and the British Landscape. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85936-120-7.

External links

Media related to River Great Ouse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to River Great Ouse at Wikimedia Commons- Useful information on the river from Jim Shead

- Drainage and Rivers of Fens

- The Ouse Washes Website

- Seal, Bluntisham