| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

|

|

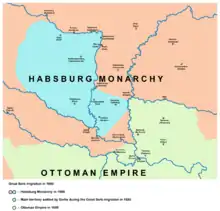

The Great Migrations of the Serbs (Serbian: Велике сеобе Срба, romanized: Velike seobe Srba), also known as the Great Exoduses of the Serbs were two migrations of Serbs from various territories under the rule of the Ottoman Empire to the Kingdom of Hungary under the Habsburg monarchy.[1][2]

The First Great Migration occurred during the Habsburg-Ottoman War (1683–1699) under Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević as a result of the Habsburg retreat and the Ottoman reoccupation of southern Serbian regions, which were temporarily held by the Habsburgs between 1688 and 1690.[3]

The Second Great Migration took place during the Habsburg-Ottoman War (1737–1739), under the Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović, also parallel with the Habsburg withdrawal from Serbian regions; between 1718 and 1739, these regions were known as the Kingdom of Serbia.[4]

The masses of earlier migrations from the Ottoman Empire are considered ethnically Serb, and those of the First Great Migration nationally Serb. The First Great Migration brought about the definitive indicator of Serbianness, Orthodox Christianity and its leader, the patriarch.[5]

Background

In 1683, the Ottoman Empire besieged Vienna, but was routed by an allied army that included the Holy Roman Empire led by the Habsburgs. The imperial forces, among whom Prince Eugene of Savoy was rapidly becoming prominent, followed up the victory with others, notably one near Mohács in 1687 and another at Zenta in 1697, and in January 1699, the sultan signed the treaty of Karlowitz by which he admitted the sovereign rights of the house of Habsburg over nearly the whole of Hungary (including Serbs in Vojvodina). As the Habsburg forces retreated, they withdrew 37,000 Serb families under Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.[6] In 1690 and 1691 Emperor Leopold I had conceived through a number of edicts (Privileges) the autonomy of Serbs in his Empire, which would last and develop for more than two centuries until its abolition in 1912. Before the conclusion of the war, however, Leopold had taken measures to strengthen his hold upon this country. In 1687, the Hungarian diet in Pressburg (now Bratislava) changed the constitution, the right of the Habsburgs to succeed to the throne without election was admitted and the emperor's elder son Joseph I was crowned hereditary king of Hungary.[7][8]

Some Serbian historians, citing a document issued by Emperor Leopold I in 1690, claim that the masses were "invited" to come to Hungary. The original text in Latin shows that Serbs were actually advised to rise up against the Ottomans and "not to desert" their ancestral lands.[9][10]

First migration

During the Austro-Turkish war (1683–1699) relations between Muslims and Christians in the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire were extremely radicalized. Following the decisive Ottoman victory in 1690 Kačanik battle in modern day Kosovo, local Orthodox Christian population was exposed to brutal reprisals of Tatars and Bosnian Muslims in Ottoman forces which indiscriminately burned villages and randomly killed or enslaved people irrespective of age, class or gender.[11] As a result of the lost rebellion and suppression, Serbian Christians and their church leaders, headed by Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III sided with the Austrians in 1689. They settled mainly in the southern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. The most important cities and places they settled are Szentendre, Buda, Mohács, Pécs, Szeged, Baja, Tokaj, Oradea, Debrecen, Kecskemét, Szatmár.[12] According to Malcolm, largest number of refugees were from the Nis region, Morava Valley and Belgrade area. Albanian Catholics and Muslims were also part of the exodus.[13]

In 1690, Emperor Leopold I allowed the refugees gathered on the banks of the Sava and Danube in Belgrade to cross the rivers and settle in the Habsburg Monarchy. He recognized Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević as their spiritual leader.[14] The Emperor had recognized the Patriarch as deputy-voivode (civil leader of the migrants), which over time developed into the etymology of the northern Serbian province of Vojvodina[14] (this origin of the name of Vojvodina is related to the fact that patriarch Arsenije III and subsequent religious leaders of Serbs in the Habsburg monarchy had jurisdiction over all Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy, including Serbs of Vojvodina, and that Serbs of Vojvodina accepted the idea of a separate Serbian voivodeship in this area, which they managed to create in 1848).

In 1694, Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor appointed Arsenije III Čarnojević as the head of the newly established Orthodox Church in the Monarchy.[15] The patriarchal right of succession was secured by the May Assembly of the Serbian people in Karlovci in 1848, following the proclamation of Serbian Vojvodina during the Serbian revolution in Habsburg lands 1848–1849.[15] Serbs received privileges from the Emperor, which guaranteed them national and religious singularity, as well as a corpus of rights and freedoms in the Habsburg monarchy.[15]

Second migration

The breakout of the Habsburg-Ottoman War (1737–1739) triggered the Second Great Migration of the Serbs. In 1737, at the very beginning of the war, Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović sided with Habsburgs and supported the rebellion of Serbs in the region of Raška against Ottomans. During the war, Habsburg armies and the Serbian Militia failed to achieve substantial success, and subsequently were forced to retreat. By 1739, entire territory of the Habsburg Kingdom of Serbia was lost to Ottomans. During the war, large portion of the Christian population from the region of Raška and other Serbian lands migrated towards the north, following the retreat of Habsburg armies and the Serbian Militia. They settled mainly in Syrmia and neighbouring regions, within the borders of the Habsburg monarchy. Among them were also the Catholic Albanian tribe Klimente, which settled in three villages in Syrmia.[4]

Number of migrants

Sources provide different data regarding the number of people in the first migration, referring to the group led by Patriarch Arsenije III:

- According to Noel Malcolm, two statements from Arsenije survive. In 1690 he wrote "more than 30,000 souls", and six years later he wrote that it was "more than 40,000 souls".[16] Malcolm also cites Cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch's statement from 1703 of more than 60,000 people led by the Patriarch from Belgrade to the Kingdom of Hungary, a figure Malcolm claims Kollonich may have been inclined to exaggerate.[16] According to Noel Malcolm, data that state that 37,000 families participated in this migration derive from a single source: a Serbian monastic chronicle which was written many years after the event and contains several other errors.[17]

- 37,000 families into Habsburg Monarchy, according to a manuscript at Šišatovac monastery written by monk Stefan of Ravanica 28 years after the first wave.[18]

- 37,000 families, according to a book by Pavle Julinac, printed in 1765.[19]

- 37,000 families led by the Patriarch, according to Jovan Rajić, published in 1794–1795.[20]

- 37,000 families led by the Patriarch, according to Johann Engel, published 1801.[21]

- Mikael Antolović studied articles by Ilarion Ruvarac who claimed that between 70,000 and 80,000 refugees left Kosovo during the migration, while the Serbian public claimed that it was more than half a million, and that the majority fled due to "fear of Ottoman vengeance".[22]

- Émile Picot concluded that it was 35,000 to 40,000 families, between 400,000 and 500,000 people. "It is a constant tradition that this population is counted by families, not by heads" also insisting that these were large extended families (see Zadruga).[23]

- The Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences, supports the figure of 37,000 families.[15]

- Tatjana Popović, cites as many as 60,000 Serbian migrant families for the First Serbian migration alone.[24]

- At least 30,000 people, according to Stevan K. Pavlowitch.[14]

- 20,000–30,000 people, according to "Teatri europei".[25]

- According to Sima Ćirković, the figure of 40,000 people is an exaggeration. He says that there is no testimony other than those of the Patriarch for a more reliable estimate.[26]

- Other historians state that only a few thousand refugees left during this time.[27]

Aftermath

Serbs from these migrations settled in the southern parts of Hungary (though as far in the north as the town of Szentendre, in which they formed the majority of the population in the 18th century, but to smaller extent also in the town of Komárom) and Croatia.

The large Serb migrations from Balkans to the Pannonian plain started in the 14th century and lasted until the end of the 18th century. The great migrations from 1690 and 1737–1739 were the largest ones and were important reason for issuing the privileges that regulated the status of Serbs within Habsburg Monarchy. The Serbs that in these migrations settled in Vojvodina, Slavonia and the parts belonging to the Military Frontier[28] increased (partly) the existing Serb population in these regions and made the Serbs an important political factor in the Habsburg monarchy over time.

The masses of earlier migrations from the Ottoman Empire are considered ethnically Serb, while those of the First Great Migration nationally Serb. The First Great Migration brought the definitive indicator of Serbianness, Orthodox Christianity and its leader, the patriarch.[29]

Modern analysis

The narrative about the migration is part of the Serbian identity narratives. It is a national-religious myth with a heroic theme.[30][10] Frederic Anscombe suggests that it, "together with other narratives of the Kosovo myth, form the basis of Serbian nationalism and have fueled the conflicts".[31] According to Anscombe, the Great Migration reconciles romantic national history with late modern reality, portraying Albanians of Kosovo as descendants of Ottoman-sponsored transplants who settled after the expulsion of the Serb population and supposedly took over the control of the territory,[32] thus replaying of a "second Battle of Kosovo"[33] and continual struggle for freedom.[32] Frederick Anscombe further concludes that there is no evidence for this,[34] and that western and parts of central Kosovo were treated as Ottoman Albania before Habsburg invasion in 1690.[35] Malcolm and Elsie state that various migrations took place because of the War of the Holy League (1683–1699), when thousands of refugees found shelter on the new Habsburg border.[36][37] Malcolm suggests that most of the Serb refugees did not come from Kosovo and that Arsenije never led an exodus from Kosovo as his departure had been extremely hasty. He notes that Toma Raspasani, who had barely escaped the Turks from Western Kosovo during the Austrian retreat, wrote himself later that "Nobody was able to get out".[38][39] Malcolm contends that Arsenije had been in Montenegro and then fled to Belgrade, a stronghold still under Austrian control, and which became a natural destination for many Serb refugees from all Serb lands.[40][41] Those who gathered there included people from parts of Kosovo (Mainly Eastern Kosovo) who had been able to escape the Ottoman incursion but most refugees were probably from other areas.[40] Among the refugees that moved to Austrian-dominated territories at the time also included a substantial number of Albanians, Orthodox and Catholics.[42]

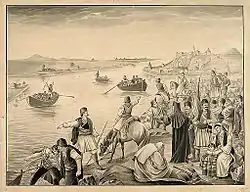

Emil Saggau states that the modern adaptation and popularisation of the migration retrieves inspiration from Vuk Karadžić and Petar II Petrović-Njegoš's writings, and that prior to this, it had not yet become a component of Serb national identity.[43] According to Maroš Melichárek, the migration has also been depicted with Serbian national symbolism. The famous painting by Paja Jovanović, commissioned in 1896 by Patriarch Georgije Branković[44] was compared with notable painting by Emanuel Leutze Washington Crossing the Delaware.[45] The depiction and symbolism of Great Serbian migration is still very strong and up-to-date. Melichárek mentions that other comparisons were made of the Great Migrations, such as to the Great Retreat and a photo of Serbs fleeing from Republika Srpska Krajina.[46]

Malcolm believes that the historical evidence does not support a sudden mass exodus of Serbs out of Kosovo in 1690.[47] If the Serb population was depleted in 1690, it looks as if it must have been replaced by inflows of Serbs from other areas.[48] Such flows did happen and from many different areas.[49] There was also a migration of Albanians from the Malsi but these were slow, long-term processes rather than involving sudden urge of population into a vacuum.[49] Considering Albanians were a significant part of the population before 1690 and that Albanian majority was not achieved until mid 19th century, a mass exodus of Serbs out of Kosovo in 1690 seems unlikely.[50] In 1689 in Kosovo, both Muslim Albanians and Serbs rose up against the Ottoman Empire led by the Albanian Archbishop Pjeter Bogdani and Toma Raspasani.[51][52]

It was after the migration of 1690, that the Ottomans first encouraged the migration of Albanians into Kosovo. The larger, eastern part of Kosovo remained overwhelmingly Serb Orthodox, with a Catholic Albanian, and later Muslim Albanian, presence growing from the west by the 16th century. The urban economy began to decline along with the output from the mines, yet Albanian highlander stockbreeders continued to migrate such that Kosovo would attain an Albanian majority by the end of 18th century.[53] The topic of the Great Migrations is a source of disputes between some Serbian and Albanian historians, with each side having its viewpoint,[42] including doubtful Serbian claims of no prior Albanian presence, and doubtful Albanian claims of a larger prior presence.[54] Additionally, Albanians claim descent from the Illyrians, who had inhabited ancient Dardania.[55][56] Albanians were present in Kosovo before the Ottoman period, and it has been suggested that a part of the Albanian population there were present as Illyrians before the Slavs came to Southeastern Europe.[57][58][59] It is likely that Albanians in Kosovo before the Ottoman period were, if not the majority, an important minority.[58] At the time of King Lazar in the 14th century, and at the beginning of the Ottoman period in 1455, the region had "an overwhelming Slavic (Serbian) majority", but significant Albanian migration in the early sixteenth century resulted by mid-century in a sizable Albanian population in parts of western Kosovo.[55] According to Malcolm, a major part of the Albanian demographic growth was the expansion of an indigenous Albanian population within Kosovo itself. [60] Ottoman official documents and reports by Evliya Çelebi in the 17th century show that before the Habsburg invasion of 1689–1690 and the Great Migrations of the Serbs, at least western and central Kosovo were treated as part of Ottoman Albania, and had a large Albanian population.[56] Thus, the Albanian tribesmen that moved from turbulent mountains of Shkodra to western and central Kosovo after 1670, merely moved to other parts of Ottoman Albania.[61] István Deák from the University of Columbia states that Serbs, who were somewhat better educated than the Albanians, were willing to move away in search of better economic opportunities, which helped demographic changes in the territory of Kosovo throughout the centuries.[62]

See also

References

- ↑ Ćirković 2004, p. 143-148, 153–154.

- ↑ Гавриловић 2014, p. 139–148.

- ↑ Ćirković 2004, p. 143-148.

- 1 2 Ćirković 2004, p. 153-154.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Miller (15 February 1998). Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8229-7722-3.

- ↑ Frazee, Charles A. (1969). The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece 1821-1852. Cambridge University Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Charles W. Ingrao (29 June 2000). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815 page 1656. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-26869-2.

- ↑ Andrew Wheatcroft (10 November 2009). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans and the Battle for Europe. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-8682-6.

- ↑ Ramet 2005, p. 206.

- 1 2 Noel Malkolm (2004). Kosovo: a chain of causes 1225 B.C. – 1991 and consequences 1991–1999. Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. pp. 1–27.

- ↑ Dejan Djokić 2023, p. 181-182.

- ↑ Melichárek 2017, p. 88.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel. A Short History of Kosovo. pp. 161–162.

- 1 2 3 Pavlowitch 2002, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 Two written statements by Arsenije survive, specifying the number of people: at the end of 1690 he gave it as "more than 30,000 souls", and six years later he wrote that it was "more than 40,000 souls". These are the most authoritative statements we have... Noel Malcolm: Albanische Geschichte: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung; by Eva Anne Frantz. p. 238

- ↑ Noel Malcolm, Kosovo – a short history, Pan Books, London, 2002, page 161.

- ↑ Stanojevic, Ljubomir. (ed) Stari srpski zapisi i natpisi, vol 3, Beograd 1905, 94, no 5283: "37000 familija"

- ↑ Pavle Julinac, Kratkoie vredeniie v istoriiu proikhozhdeniia slaveno-serbskago naroda. Venetiis 1765 (ed. Miroslav Pantic, Belgrade, 1981), p. 156: numbers derived from an official Imperial report to Vienna.

- ↑ Jovan Rajić, Istoriia raznikh slavenskikh narodov, naipache Bolgar, Khorvatov, i Serbov, vol 4, 1795, p. 135: "37000 familii Serbskikh s Patriarkhom

- ↑ Engel, Johann Christian von, Geschichte des ungrischen Reichs und seiner Nebenländer, vol. 3. Halle 1801, 485: "37000 Serwische Familien, mit ihrem Patriarchen"

- ↑ Antolović, Michael (2016). "Modern Serbian Historiography between Nation-Building and Critical Scholarship: The Case of Ilarion Ruvarac (1832–1905)". The Hungarian Historical Review. 5 (2): 332–356. JSTOR 44390760.

- ↑ A.E. Picot, Les Serbes de Hongrie, 1873, p. 75

- ↑ Popović 1988, p. 28.

- ↑ Aleksandar Protić, Još koja o istom, Seoba u sporovima, Novi Sad, 1991, page 91.

- ↑ Sima M. Cirkovic (2004). The Serbs. Wiley. p. 144.

- ↑ Máiz, Ramón; William, Safran (2014). Identity and Territorial Autonomy in Plural Societies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-30401-0.

- ↑ Mutschlechner, Martin. "The Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy". Der Erste Weltkrieg.

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ J. M. Fraser (1998). International Journal. Canadian Institute of International Affairs. p. 603.

- ↑ Dan Landis; Rosita D. Albert (2012). Handbook of Ethnic Conflict: International Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 351. ISBN 9781461404477.

- 1 2 Melichárek 2017, p. 93.

- ↑ Frederick F., Anscombe (2006). The Ottoman Empire in recent international politics II: the case of Kosovo. The International History Review (PDF). Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College. pp. 767, 769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Anscombe, Frederick 2006 P. 780

- ↑ Anscombe Frederick 2006

- ↑ Anscombe, ibid.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2004). Historical Dictionary of Kosova. Scarecrow Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8108-5309-6. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, pp. 137–141.

- ↑ Kosovo: A Short History. p.158

- 1 2 Malcolm 2020, p. 138.

- ↑ Kosovo: A Short History

- 1 2 Shinasi A. Rama (2019). Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosova. Springer. p. 64.

- ↑ Emil Hilton, Saggau (2019). Kosovo Crucified—Narratives in the Contemporary Serbian Orthodox Perception of Kosovo. University of Copenhagen: Department for Church History. pp. 6, 10, 11. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Tim, Judah. "washingtonpost.com: The Serbs". www.washingtonpost.com. No. The original painting was commissioned in 1896 by Patriarch Georgije Brankovic. The artist was Paja Jovanovic. He was one of the most illustrious Serbian painters of his generation and his depictions of the greatest moments of Serbian history placed him firmly at the centre of the national artistic renaissance of the time. Washington Post. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Melichárek 2017, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Melichárek 2017, p. 88-89.

- ↑ Kosovo: A Short History. p. 158-159

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 128-129, 143.

- 1 2 Malcolm 2020, p. 143.

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 132.

- ↑ Malcolm 2020, p. 134.

- ↑ 1689 | Kosovo In The Great Turkish War – Translated by Robert Elsie, From Austrian Archive

- ↑ Lampe, John R.; Lampe, Professor John R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country "The first ottoman encouragement of Albanian migration did follow the Serb exodus of 1690". Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Lampe, John R.; Lampe, Professor John R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

Subsequent controversy has swirled around doubtful Albanian claims of a larger initial presence and doubtful Serbian claims of virtually no Albanian presence until Ottoman pressure pushed them in for religious as well as political reasons.

- 1 2 Cohen, Paul (2014). History and Popular Memory. Columbia University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780231537292.

- 1 2 Frederick F., Anscombe (2006). The Ottoman Empire in recent international politics II: the case of Kosovo. The International History Review (PDF). Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College. pp. 784–788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 9780333666128.

- 1 2 Ducellier, Alain (2006). The case for Kosova. Anthem Press. p. 34.

- ↑ King, Iain (2011). Peace at Any Price: How the World Failed Kosovo. p. 26.

- ↑ Kosovo: A Short History. p. 36 , p. 112 , p. 111

- ↑ Frederick F., Anscombe (2006). The Ottoman Empire in recent international politics II: the case of Kosovo. The International History Review (PDF). Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College. p. 791. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty June (2017). Education in the People's Republic of China, Past and Present (PDF) (In general, families, clans, and tribes moved, settled, converted, and reconverted in the Balkans; only in modern times have such acts become a major political issue. No doubt, the proportion of Albanian-speaking Muslims has increased in Kosovo over the centuries, so that today they form the overwhelming majority, but this was due, in part, to the willingness of local Serbs, somewhat better educated than the Albanians, to move away in search of better economic opportunities. ed.). p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Cox, John K. (2002). The History of Serbia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313312908.

- Dejan Djokić (2023). A Concise History of Serbia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02838-8.

- Đorđević, Života; Pejić, Svetlana, eds. (1999). Cultural Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija. Belgrade: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 9788680879161.

- Гавриловић, Владан С. (2014). "Примери миграција српског народа у угарске провинцијалне области 1699-1737" [Examples of Serbian Migrations to Hungarian Provincial Districts 1699–1737]. Истраживања (in Serbian). Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду. 25: 139–148.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274586.

- Katić, Tatjana (2012). Tursko osvajanje Srbije 1690. godine [The Ottoman Conquest of Serbia in 1690.] (in Serbian). Beograd: Srpski genealoški centar, Centar za osmanističke studije.

- Miller, Nicholas J. (1997). Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822939894.

- Malcolm, Noel (2020). Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the History of the Albanians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198857297.</ref>

- Melichárek, Maroš (2017). "Great Migration of the Serbs (1690) and its Reflections in Modern Historiography". Serbian Studies Research. 8 (1): 87–102.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654773.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815624448.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2005). Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521616904.

- Samardžić, Radovan (1989). "Migrations in Serbian History (The Era of Foreign Rule)". Migrations in Balkan History. Belgrade: Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 83–89. ISBN 9788671790062.

- Томић, Јован Н. (1902). Десет година из историје српског народа и цркве под Турцима (1683-1693) (PDF). Београд: Државна штампарија.

- Трифуноски, Јован Ф. (1990). "Велика сеоба Срба у народним предањима из Македоније" [The Great Serbian Migration in Folk Legends from Macedonia] (PDF). Етнолошке свеске (in Serbian). 11: 54–61.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R. (1989). "Wars, Population Migrations and Religious Proselytism in Dalmatia during the Second Half of the XVIIth Century". Migrations in Balkan History. Belgrade: Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 77–82. ISBN 9788671790062.

External links

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. "Velika seoba Srba u Austriju". Istorija srpskog naroda. Projekat Rastko.