| River Tay Tatha | |

|---|---|

Looking upstream (north) along the Tay from the centre of Perth. In view are St Matthew's Church and Perth Bridge | |

| Location | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Allt Coire Laoigh |

| • location | Ben Lui, Stirling council area / Argyll and Bute, Scotland |

| • coordinates | 56°23′07″N 4°47′36″W / 56.38528°N 4.79333°W |

| • elevation | 720 m (2,360 ft) |

| Mouth | Firth of Tay, North Sea |

• location | Between Perth, Scotland and Dundee, Scotland, UK |

• coordinates | 56°21′18″N 3°17′54″W / 56.35500°N 3.29833°W |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 193 km (120 mi) |

| Basin size | 4,970 km2 (1,920 sq mi) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | River Lyon, River Tummel, River Isla |

| • right | River Almond, River Earn, River Braan |

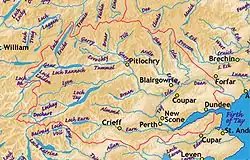

The River Tay (Scottish Gaelic: Tatha, IPA: [ˈt̪ʰa.ə]; probably from the conjectured Brythonic Tausa, possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing'[1]) is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates in western Scotland on the slopes of Ben Lui (Scottish Gaelic: Beinn Laoigh), then flows easterly across the Highlands, through Loch Dochart, Loch Iubhair and Loch Tay, then continues east through Strathtay (see Strath), in the centre of Scotland, then southeasterly through Perth, where it becomes tidal, to its mouth at the Firth of Tay, south of Dundee. It is the largest river in the United Kingdom by measured discharge.[2] Its catchment is approximately 2,000 square miles (5,200 square kilometres), the Tweed's is 1,500 sq mi (3,900 km2) and the Spey's is 1,097 sq mi (2,840 km2).

The river has given its name to Perth's Tay Street, which runs along its western banks for 830 yards (760 metres).

Course

The Tay drains much of the lower region of the Highlands. It originates on the slopes of Ben Lui (Beinn Laoigh), around 25 mi (40 km) from the west coast town of Oban, in Argyll and Bute.[2] In 2011, the Tay Western Catchments Partnership determined as its source (as based on its 'most dominant and longest' tributary) a small lochan on Allt Coire Laoigh south of the summit.[3] The river has a variety of names in its upper catchment: for the first few miles it is known as the River Connonish; then the River Fillan; the name then changes to the River Dochart until it flows into Loch Tay at Killin.

The River Tay emerges from Loch Tay at Kenmore, and flows from there to Perth which, in historical times, was its lowest bridging point. Below Perth the river becomes tidal and enters the Firth of Tay. The largest city on the river, Dundee, lies on the north bank of the Firth. On reaching the North Sea, the River Tay has flowed 120 mi (190 km)[4] from west to east across central Scotland.

The Tay is unusual amongst Scottish rivers in having several major tributaries, notably the Earn, the Isla, the River Tummel, the Almond and the Lyon.[2]

A flow of 2,268 m3/s (80,100 cu ft/s) was recorded on 17 January 1993, when the river rose 6.48 m (21 ft 3 in) above its usual level at Perth, and caused extensive flooding in the city. Were it not for the hydro-electric schemes upstream which impounded runoff, the peak would have been considerably higher. The highest flood recorded at Perth occurred in 1814, when the river rose 7 m (23 ft) above its usual level, partly caused by a blockage of ice under Smeaton's Bridge.[5]

Several places along the Tay take their names from it, or are believed to have done so:

Nature and conservation

The river is of high biodiversity value and is both a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a Special Area of Conservation. The SAC designation notes the river's importance for salmon (Salmo salar), otters (Lutra lutra), brook lampreys (Lampetra planeri), river lampreys (Lampetra fluviatilis), and sea lampreys (Petromyzon marinus).[6] The Tay also maintains flagship population of freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera).[2] Freshwater pearl mussels are one of Scotland's most endangered species and the country hosts two-thirds of the world's remaining stock.[7]

The Tay is internationally renowned for its salmon fishing and is one of the best salmon rivers in western Europe, attracting anglers from all over the world. The lowest ten miles (sixteen kilometres) of the Tay, including prestigious beats like Taymount or Islamouth, provides most of the cream of the Tay. The largest rod-caught salmon in Britain, caught on the Tay by Georgina Ballantine in 1922, weighing 64 pounds (29 kilograms), retains the British record. The river system has salmon fisheries on many of its tributaries including the Earn, Isla, Ericht, Tummel, Garry, Dochart, Lyon and Eden.[8] Dwindling catches include a 50% reduction in 2009 so the Tay District Salmon Fisheries Board ordered a catch-and-release policy for females all season, and for males until May, beginning in the January 2010 fishing season. Research by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation has shown that the number of salmon dying at sea has doubled or trebled over the past 20 years, possibly due to overfishing in the oceans where salmon spend two years before returning to freshwater to spawn. The widespread collapse in Atlantic salmon stocks suggests that this is not solely a local problem in the River Tay.[9]

A section of the Tay surrounding the town of Dunkeld is designated as a national scenic area (NSA),[10] one of 40 such areas in Scotland, which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection by restricting certain forms of development.[11] The River Tay (Dunkeld) NSA covers 5,708 ha.[12]

The first sustained and significant population Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) living wild in Scotland in over 400 years became established on the river Tay catchment in Scotland as early as 2001, and has spread widely in the catchment, numbering from 20 to 100 individuals in 2011.[13] These beavers were likely to be either escapees from any of several nearby sites with captive beavers, or were illegally released, and were originally targeted for removal by Scottish Natural Heritage in late 2010.[14] Proponents of the beavers argued that no reason exists to believe that they are of "wrong" genetic stock.[13] In early December 2010, the first of the wild Tayside beavers was trapped by Scottish Natural Heritage on the River Ericht in Blairgowrie, Perthshire and was held in captivity in Edinburgh Zoo, dying within a few months.[15] In March 2012 the Scottish Government reversed the decision to remove beavers from the Tay, pending the outcome of studies into the suitability of re-introduction.[16]

As part of the study into re-introduction, a trial release project was undertaken in Knapdale, Argyll,[17][18][19] alongside which the population of beavers along the Tay was monitored and assessed.[16] Following the conclusion of the trial re-introduction, the Scottish Government announced in November 2016 that beavers could remain permanently, and would be given protected status as a native species within Scotland. Beavers will be allowed to extend their range naturally. To aid this process and improve the health and resilience of the population a further 28 beavers will be released in Knapdale between 2017 and 2020,[20] however there are no plans at present to release further beavers into the Tay.

Transport

In the 19th century the Tay Rail Bridge was built across the firth at Dundee as part of the East Coast Main Line, which linked Aberdeen in the north with Edinburgh and London to the south. The bridge, designed by Sir Thomas Bouch, officially opened in May 1878. On 28 December 1879 the bridge collapsed as a train passed over. The entire train fell into the firth, with the loss of 75 passengers and train crew. The event was commemorated in a poem, The Tay Bridge Disaster (1880), written by William McGonagall, a notoriously unskilled Scottish poet. The critical response to his article was enhanced as he had previously written two poems celebrating the strength and certain immortality of the Tay Bridge. A second much more well received poem was published in the same year by the German writer Theodor Fontane.[21] A. J. Cronin's first novel, Hatter's Castle (1931), includes a scene involving the Tay Bridge Disaster, and the 1942 filmed version of the book recreates the bridge's catastrophic collapse. The rail bridge was rebuilt, with the replacement bridge opening on 11 June 1887.

A passenger and vehicle ferry service operated across the River Tay between Craig Pier, Dundee and Newport-on-Tay in Fife. In Dundee, the ferries were known as "the Fifies".[22] The service was discontinued on the opening of the Tay Road Bridge on 18 August 1966.

The last vessels to operate the service were PS B. L. Nairn and two more modern ferries equipped with Voith Schneider Propellers, MVs Abercraig and Scotscraig.

Cultural references

The Tay bridge is the subject of William McGonagall's poems "Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay" and "The Tay Bridge Disaster", and in the German poet Theodor Fontane's poem "Die Brück' am Tay". Both deal with the Tay bridge disaster of 1879, seeing the bridge's construction as a case of human hubris and expressing an uneasiness towards the fast technological development of mankind.[21]

The river is mentioned in passing in the Steeleye Span song "The Royal Forester". Symphonic power metal band Gloryhammer mentioned the river in some of their songs as "silvery Tay" or "mighty river Tay".[23][24] Many Rolls-Royce civil aero-engines are named after British rivers, one of which is the Rolls-Royce Tay.

See also

References

- ↑ David Ross, Scottish Place-names, p. 209. Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 River Tay, United Kingdom (PDF) (Report). Peer-Euraqua network of hydrological observatories. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ↑ "BBC News - Source of River Tay 'pinpointed'". BBC News.

- ↑ Clayton, Phil (2012). Headwaters: Walking to British River Sources (First ed.). London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 204. ISBN 9780711233638.

- ↑ Black, Andrew (18 January 2018). "Remembering the Great Tay Flood of January 1993". Dundee Hydrology. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ↑ "River Tay SAC". NatureScot. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ River Tay Special Area of Conservation (SAC) - Advice to developers when considering new projects which could affect the River Tay Special Area of Conservation (PDF) (Report). Scottish Natural Heritage. p. 6. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ "Fish Tay". FishPal. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ Frank Urquhart (11 January 2010). "In Scotland, Anglers Told to Put River Tay Salmon Back". Atlantic Salmon Federation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ "River Tay (Dunkeld) National Scenic Area". NatureScot. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas". NatureScot. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas - Maps". Scottish Natural Heritage. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 Duncan J. Halley (January 2011). "Sourcing Eurasian beaver Castor fiber stock for reintroductions in Great Britain and Western Europe". Mammal Review. 41: 40–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00167.x.

- ↑ Iain Howie (3 December 2010). "Perthshire beavers to be rounded up". Perthshire Advertiser. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ↑ "Sole trapped beaver Erica died in captivity". Courier News. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- 1 2 "Plan to trap River Tay beavers reversed by ministers". BBC News. 16 March 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers to return after 400 years". BBC News. 25 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers return after 400-year gap". BBC News. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "About the trial". www.scottishbeavers.org.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "Beaver population increased in Knapdale". Scottish Wildlife Trust. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 Edward C. Smith III: The Collapse of the Tay Bridge: Theodor Fontane, William McGonagall, and the Poetic Response to the Humanity's First Technologocal Disaster. In: Ray Broadus Browne (ed.), Arthur G. Neal (ed.): Ordinary Reactions to Extraordinary Events. Popular Press (Ohio State University), 2001, ISBN 9780879728342, pp. 182-193

- ↑ "The Making of Modern Dundee" (PDF). www.themcmanus-dundee.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ↑ "Gloryhammer - Legends from Beyond the Galactic Terrorvortex - Encyclopaedia Metallum: The Metal Archives". www.metal-archives.com. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ "Gloryhammer - The Epic Rage of Furious Thunder Songtext". Songtexte.com (in German). Retrieved 11 October 2023.

Further reading

- From the Ganga to the Tay by Bashabi Fraser, 2009. Luath Press Ltd. ISBN 1906307954.