35°03′48″N 24°56′49″E / 35.0632209°N 24.9469189°E

The Gortyn code (also called the Great Code[1]) was a legal code that was the codification of the civil law of the ancient Greek city-state of Gortyn in southern Crete.

History

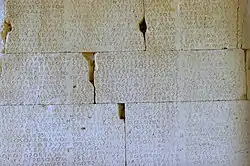

Our sole source of knowledge of the code is the fragmentary boustrophedon inscription[2] on the circular walls of what might have been a bouleuterion or other public civic building in the agora of Gortyn. The original building was 30 m (100 ft) in diameter; the 12 columns of text which survive are 10 m (30 ft) in length and 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in height and contain some 600 lines of text. In addition, some further broken texts survive; the so-called second text.[3] It is the longest extant ancient Greek inscription except for the inscription of Diogenes of Oenoanda. Evidence suggests it is the work of a single sculptor. The inscription has been dated to the first half of the 5th century BCE.[4]

The first fragment of the code was discovered in 1857 by Georges Perrot and Louis Thenon. Italian archaeologist Federico Halbherr found a further four columns of the text while excavating a site near a local mill in 1884. Since this was evidently part of a larger text, he, with Ernst Fabricius and a team, obtained permission to excavate the rest of the site, revealing 8 more text columns whose stones had been reused as part of the foundations of a Roman Odeion from the 1st century BCE. The wall bearing the code has now been partially reconstructed.

The Great Code is written in the Dorian dialect and is one of a number of legal inscriptions found scattered across Crete but curiously, very few nonlegal texts from ancient Crete survive.[5] The Dorian language was then pervasive among Cretan cities such as Knossos, Lyttos, Axos and various other areas of central Crete.[6] The Code stands with a tradition of Cretan law, which taken as a totality represents the only substantial corpus of Greek law from antiquity found outside Athens. The whole corpus of Cretan law may be divided into three broad categories: the earliest (I. Cret. IV 1-40., ca. 600 BCE to ca. 525 BCE) was inscribed on the steps and walls of the temple of Apollo Pythios, the next a sequence, including the Great Code, written on the walls in or near the agora between ca. 525 and 400 BCE (I. Cret. IV 41-140), followed by the laws (I. Cret. IV 141-159), which contain Ionian characters and so are dated to the 4th century.

Though all the texts are fragmentary and show evidence of a continuous amendment of the law,[7] it has been possible to trace the development of the law from Archaic proscriptions onwards, notably the diminishing rights of women and the increasing rights of slaves. Also, one can infer some aspects of public law.

Content

The code deals with such matters as disputed ownership of slaves, rape and adultery, the rights of a wife when divorced or a widow, the custody of children born after divorce, inheritance, sale and mortgaging of property, ransom, children of mixed (slave, free and foreign) marriages and adoption.[8] The code makes legal distinctions between different social classes. Free, serf, slave and foreigner social statuses are recognized within the document.

Bringing suit

The code provides a measure of protection for individuals prior to their trial. Persons bringing suit are prohibited from seizing and detaining the accused before trial. Violations are punishable by fines, which vary depending on the status of the detained individual.

Rape and adultery

Rape under the code is punished with fines. The fine is largely determined by the difference in social status between the victim and the accused. A free man convicted of raping a serf or a slave would receive the lowest fine; a slave convicted of raping a free man or woman would warrant the highest fine.

Adultery is punished similarly to rape under the code but also takes into consideration the location of the crime. The code dictates higher fines for adultery committed within the household of the female's father, husband or brother, as opposed to another location. Fines also depend on whether the woman has previously committed adultery. The fines are levied against the male involved in the adultery, not the female. The code does not provide for the punishment of the female.

Divorce and marriage rights

The Gortyn law code grants a modicum of property rights to women in the case of divorce. Divorced women are entitled to any property that they brought to the marriage and half of the joint income if derived from her property. The code also provides for a portion of the household property. The code stipulates that any children conceived before the divorce but born after the divorce fall under the custody of the father. If the father does not accept the child, it reverts to the mother.

Property rights and inheritance

The code devotes a great deal of attention to the allocation and management of property. Although the husband manages the majority of the family property, the wife's property is still delineated. If the wife dies, the husband becomes the trustee to her property and may take no action on it without the consent of her children. In the case of remarriage, the first wife's property immediately comes into her children's possession. If the wife dies childless, her property reverts to her blood relatives.

If the husband dies with children, the property is held in trust by the wife for the children. If the children are of age upon their father's death, the property is divided between the children, with males receiving all of the land. If the husband dies without any children, the wife is compelled to remarry.

Adopted children receive all the inheritance rights of natural children and are considered legitimate heirs in all cases. Women are not allowed to adopt children.[6]

Gallery

The Amphitheatre containing the Gortyn code.

The Amphitheatre containing the Gortyn code. Inscription of the Great Code at Gortyn.

Inscription of the Great Code at Gortyn. Photomontage of the Gortyn Code.

Photomontage of the Gortyn Code. Complete transcription of the 12 columns of the Gortyn Code, with the boustrophedon writing retained.

Complete transcription of the 12 columns of the Gortyn Code, with the boustrophedon writing retained.

See also

References

- ↑ I. Cret. IV.72

- ↑ The terms "Gortyn code" and "Great Code" may be used interchangeably for the text and the inscription.

- ↑ I. Cret. IV 41-50

- ↑ Willets 1967, p. 8

- ↑ See J. Whitley The Archaeology of Ancient Greece p. 248 for a statistical analysis.

- 1 2 see Willetts, "The Law Code of Gortyn"

- ↑ See J. Davies:Deconstructing Gortyn: When is a CODE a Code?, in Greek Law in its Political Setting L Foxhall, ADE Lewis (eds).

- ↑ For a full discussion of the text see John Davies: The Gortyn Laws in The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law, pp. 305-327.

- ↑ "loi de Gortyne". Louvre. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

Sources

- M. Guarducci, Inscriptiones Creticae, 1935-1950.

- R. F. Willetts, The Law Code of Gortyn, 1967.

- Michael Gagarin, David J. Cohen (eds), Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law, 2005.

- J. Whitley, "Cretan Laws and Cretan Literacy", American Journal of Archaeology, 101(4), 1997.

- Ilias Arnaoutoglou, Ancient Greek Laws, 1998.

- M. Harris, Lene Rubinstein (eds), The Law and the Courts in Ancient Greece, 2004.

- Michael Gagarin, Writing Greek Law, 2008.

External links

- The Law Code of Gortyn (Crete), c. 450 BCE from Ancient History Sourcebook

- PHI 200508 The Packard Humanities Institute (full Greek text after Willetts 1967).

- Codificiation, tradition and innovation in the law code of Gortyn

- The Law Code of Gortyn / ed. with introduction, transl. and a commentary by Ronald F. Willets. downloadable pdf.