| Operation Flavius | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Troubles | |

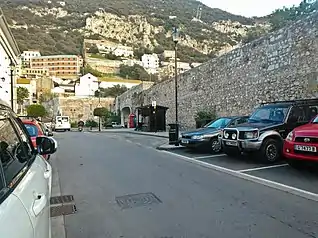

Petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue in Gibraltar, where McCann and Farrell were shot, pictured in 2014 | |

| Type | Shooting |

| Location | 36°08′48″N 5°21′01″W / 36.1467°N 5.3503°W |

| Date | 6 March 1988 |

Operation Flavius (also referred to as the Gibraltar killings) was a military operation in which three members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) were controversially shot dead by the British Special Air Service (SAS) in Gibraltar on 6 March 1988.[1][2] The trio were believed to be planning a car bomb attack on British military personnel in Gibraltar. They were shot dead while leaving the territory, having parked a car. All three were found to be unarmed, and no bomb was discovered in the car, leading to accusations that the British government had conspired to murder them. An inquest in Gibraltar ruled that the authorities had acted lawfully but the European Court of Human Rights held that, although there had been no conspiracy, the planning and control of the operation was so flawed as to make the use of lethal force almost inevitable. The deaths were the first in a chain of violent events in a fourteen-day period. On 16 March, the funeral of the three IRA members was attacked, leaving three mourners dead. At the funeral of one, two British soldiers were killed after driving into the procession in error.

In late 1987, British authorities became aware of an IRA plan to detonate a bomb outside the governor's residence in Gibraltar. On the day of the shootings, known IRA member Seán Savage was seen parking a car near the assembly area for the parade; fellow members Daniel McCann and Mairéad Farrell were seen crossing the border shortly afterwards. As SAS personnel moved to intercept the three, Savage split from McCann and Farrell and ran south. Two soldiers pursued Savage while two others approached McCann and Farrell. The soldiers reported seeing the IRA members make threatening movements when challenged, so the soldiers shot them multiple times. All three were found to be unarmed, and Savage's car did not contain a bomb, though a second car, containing explosives, was later found in Spain. Two months after the shootings, the documentary "Death on the Rock" was broadcast on British television. Using reconstructions and eyewitness accounts, it presented the possibility that the three IRA members had been unlawfully killed.

The inquest into the deaths began in September 1988. The authorities stated that the IRA team had been tracked to Málaga, where they were lost by the Spanish police, and that the three did not re-emerge until Savage was seen parking his car in Gibraltar. The soldiers testified that they believed the suspected bombers had been reaching for weapons or a remote detonator. Several eyewitnesses recalled seeing the three shot without warning, with their hands up, or while they were on the ground. One witness, who told "Death on the Rock" he saw a soldier fire at Savage repeatedly while he was on the ground, retracted his statement at the inquest, prompting an inquiry into the programme which largely vindicated it. The inquest returned a verdict of lawful killing. Dissatisfied, the families took the case to the European Court of Human Rights. Delivering its judgement in 1995, the court found that the operation had been in violation of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights as the authorities' failure to arrest the suspects at the border, combined with the information given to the soldiers, rendered the use of lethal force almost inevitable. The decision is cited as a landmark case in the use of force by the state.

Background

| History of Gibraltar |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) aimed to establish a united Ireland and end the British administration of Northern Ireland through the use of force. The organisation was the result of a 1969 split in the Irish Republican Army;[3] the other group, the Official IRA, ceased paramilitary activity in the 1970s. The IRA killed civilians, members of the armed forces, police, judiciary and prison service, including off-duty and retired members, and bombed businesses and military targets in both Northern Ireland and England, with the aim of making Northern Ireland ungovernable.[4][5] Daniel McCann, Seán Savage, and Mairéad Farrell were, according to the journalist Brendan O'Brien, "three of the IRA's most senior activists".[6] Savage was an explosives expert and McCann was "a high-ranking intelligence operative"; both McCann and Farrell had previously served prison sentences for offences relating to explosives.[6][7][8]

The Special Air Service is part of the United Kingdom's special forces. The SAS was first assigned to operations in Northern Ireland in the early stages of the British Army's deployment there, but were confined to South Armagh. More widespread deployment of the SAS began in 1976, when D Squadron was committed.[9] The SAS specialised in covert, intelligence-based operations against the IRA, using more aggressive tactics than regular army and police units.[10][11]

Build-up

From late 1987, the British authorities were aware that the IRA was planning an attack in Gibraltar. The intelligence appeared to be confirmed in November 1987, when several known IRA members were detected travelling from Belfast to Spain under false identities. MI5—the British Security Service—and the Spanish authorities became aware that an IRA active service unit (ASU) was operating from the Costa del Sol and the members of the unit were placed under surveillance. After a known IRA member was sighted at the changing of the guard ceremony at the Convent (the governor's residence) in Gibraltar, the authorities suspected that the IRA was planning to attack the British soldiers with a car bomb as they assembled for the ceremony in a nearby car park. In an attempt to confirm the IRA's intended target, the government of Gibraltar suspended the ceremony in December 1987, citing a need to repaint the guardhouse. They believed their suspicions were confirmed when the IRA member re-appeared at the ceremony in February 1988.[12]

In the following weeks, Savage, McCann, and Farrell travelled to Málaga (90 miles [140 kilometres] along the coast from Gibraltar), where they each rented a car.[13] Their activities were monitored and by early March, the British authorities were convinced that an IRA attack was imminent; a team from the SAS was despatched to the territory, apparently with the personal approval of the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.[14] Before the operation, the SAS practised arrest techniques, while the Gibraltar authorities searched for a suitable place to hold the would-be bombers after their arrest.[15] The plan was that the SAS would assist the Gibraltar Police in arresting the IRA members—identified by MI5 officers who had been in Gibraltar for several weeks—if they were seen parking a car in Gibraltar and then attempting to leave the territory.[16]

Events of 6 March

According to the official account of the operation, Savage entered Gibraltar undetected at 12:45 (CET; UTC+1) on 6 March 1988 in a white Renault 5. An MI5 officer recognised him and he was followed, but he was not positively identified for almost an hour and a half, during which time he parked the vehicle in the car park used as the assembly area for the changing of the guard. At 14:30, McCann and Farrell were observed crossing the frontier from Spain and were also followed.[17] They met Savage in the car park at around 14:50 and a few minutes later the three began walking through the town. After the three left the car park, "Soldier G",[note 1] a bomb-disposal officer, examined Savage's car and reported that the vehicle should be treated as a possible car bomb. Soldier G's suspicion was conveyed as certainty to four SAS troopers, Soldiers "A", "B", "C", and "D". Gibraltar Police Commissioner Joseph Canepa handed control of the operation to "Soldier F", the senior SAS officer, at 15:40.[19] Two minutes later, the SAS moved to intercept the IRA operatives as they walked north on Winston Churchill Avenue towards the Spanish border. As the soldiers approached, the suspects appeared to realise that they were being followed. Savage split from the group and began heading south, brushing against "Soldier A" as he did so; "A" and "B" stayed with McCann and Farrell and Soldiers "C" and "D" followed Savage.[20]

At the same time as the police handed control over to the SAS, they began making arrangements for the IRA members once they were in custody, including finding a police vehicle in which to transport the prisoners. A patrol car containing Inspector Luis Revagliatte and three other uniformed officers, apparently on routine patrol and with no knowledge of Operation Flavius, was ordered to return to police headquarters as a matter of urgency. The police car was stuck in heavy traffic travelling north on Smith Dorrien Avenue, close to the roundabout where it meets Winston Churchill Avenue.[21] The official account states that at this point, Revagliatte's driver activated the siren on the police car to expedite the journey, intending to approach the roundabout from the wrong side of the road and turn the vehicle around. The siren apparently startled McCann and Farrell, just as Soldiers "A" and "B" were about to challenge them, outside the petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue.[22]

"Soldier A" stated at the inquest that Farrell looked back at him and appeared to realise who "A" was; "A" testified that he was drawing his pistol and intended to shout a challenge to her, but "events overtook the warning": that McCann's right arm "moved aggressively across the front of his body", leading "A" to believe that McCann was reaching for a remote detonator. "A" shot McCann once in the back; he told the inquest he believed Farrell then reached for her handbag, and that he believed Farrell may also have been reaching for a remote detonator. He shot Farrell once in the back, before returning to McCann—he shot McCann a further three times (once in the body and twice in the head). "Soldier B" testified that he reached similar conclusions to "A", and shot Farrell twice, then McCann once or twice, then returned to Farrell, shooting her a further three times. Soldiers "C" and "D" testified at the inquest that they were moving to apprehend Savage, who was by now 300 feet (91 metres) south of the petrol station, as gunfire began behind them. "Soldier C" testified that Savage turned around while simultaneously reaching towards his jacket pocket at the same time as "C" shouted "Stop!"; "C" stated that he believed Savage was reaching for a remote detonator and so opened fire. "C" shot Savage six times, while "Soldier D" fired nine times.[23] All three IRA members died. One of the soldiers' bullets, believed to have passed through Farrell, grazed a passer-by.[24][25][26]

Immediately after the shootings, the soldiers donned berets to identify themselves. Gibraltar Police officers, including Inspector Revagliatte and his men, began to arrive at the scene almost immediately.[27] At 16:05, 25 minutes after assuming control, the SAS commander handed control of the operation back to the Gibraltar Police in a document stating: "A military assault force completed the military option in respect of the terrorist ASU in Gibraltar and returns control to the civil power."[27] Soldiers and police officers evacuated buildings in the vicinity of the Convent and bomb-disposal experts were brought in. Four hours later, the authorities announced that a car bomb had been defused. The SAS personnel left Gibraltar by military aircraft the same day.[28]

When the bodies were searched, a set of car keys was found on Farrell. Spanish and British authorities conducted enquiries to trace the vehicle, which—two days after the shootings—led them to a red Ford Fiesta in a car park in Marbella (50 miles [80 kilometres] from Gibraltar). The car contained a large quantity of Semtex surrounded by 200 rounds of ammunition, along with four detonators and two timers.[29][30]

Reaction

Within minutes, the British Ministry of Defence (MoD) said in a press release that "a suspected car bomb has been found in Gibraltar, and three suspects have been shot dead by the civilian police".[31] That evening, both the BBC and ITN reported that the IRA team had been involved in a "shootout" with the authorities. The following morning, BBC Radio 4 reported that the alleged bomb was "packed with bits of metal and shrapnel", and later carried a statement from Ian Stewart, Minister of State for the Armed Forces, that "military personnel were involved. A car bomb was found, which has been defused". All eleven British daily newspapers reported the alleged finding of the car bomb, of which eight quoted its size as 500 pounds (230 kilograms). The IRA issued a statement later on 7 March to the effect that McCann, Savage, and Farrell were "on active service" in Gibraltar and had "access to and control over 140 pounds (64 kg)" of Semtex.[31][32]

According to one case study of the incident, it "provide[d] an opportunity to examine the ideological functioning of the news media within [the Troubles]".[33] The British broadsheet newspapers all exhibited what the authors called "ideological closure" by marginalising the IRA and extolling the SAS. Several papers focused on the size of the alleged bomb and the devastation it could have caused without questioning the government's version of events.[33] At 15:30 (GMT) on 7 March, the foreign secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe, made a statement to the House of Commons:[34][35]

Shortly before 1:00 p.m. yesterday, afternoon [Savage] brought a white Renault car into Gibraltar and was seen to park it in the area where the guard mounting ceremony assembles. Before leaving the car, he was seen to spend some time making adjustments in the vehicle

An hour and a half later, [McCann and Farrell] were seen to enter Gibraltar on foot and shortly before 3:00 p.m., joined [Savage] in the town. Their presence and actions near the parked Renault car gave rise to strong suspicions that it contained a bomb, which appeared to be corroborated by a rapid technical examination of the car.

About 3:30 p.m., all three left the scene and started to walk back towards the border. On their way to the border, they were challenged by the security forces. When challenged, they made movements which led the military personnel, operating in support of the Gibraltar Police, to conclude that their own lives and the lives of others were under threat. In light of this response, they [the IRA members] were shot. Those killed were subsequently found not to have been carrying arms.

The parked Renault car was subsequently dealt with by a military bomb-disposal team. It has now been established that it did not contain an explosive device.

Press coverage in the following days, after Howe's statement that no bomb had been found, continued to focus on the act planned by the IRA; several newspapers reported a search for a fourth member of the team. Reports of the discovery of the bomb in Marbella appeared to vindicate the government's version of events and justify the killings. Several MPs made statements critical of the operation, while a group of Labour MPs tabled a condemnatory motion.[36]

Aftermath

The IRA notified the McCann, Savage, and Farrell families of the deaths on the evening of 6 March,[37] and the following day publicly announced that the three were members of the IRA.[38] A senior member of Sinn Féin, Joe Austin, was tasked with recovering the bodies. On 9 March, he and Terence Farrell (Mairéad Farrell's brother) travelled to Gibraltar to identify the bodies. Austin negotiated a charter aircraft to collect the corpses from Gibraltar and fly them to Dublin on 14 March. In 2017 it emerged that Charles Haughey had secretly requested that the Royal Air Force fly the bodies direct to Belfast, bypassing the Republic of which he was Taoiseach.[39] Two thousand people waited to meet the coffins in Dublin, which were then driven north to Belfast.[40] At the border, the Northern Irish authorities met the procession with a large number of police and military vehicles, and insisted on intervals between the hearses, causing tensions between police and members of the procession and leading to accusations that the police rammed Savage's hearse.[41][42]

The animosity continued until the procession split to allow the hearses to travel to the respective family homes. British soldiers and police flooded the neighbourhoods to try to prevent public displays of sympathy for the dead. Later that evening, a local IRA member, Kevin McCracken, was shot and allegedly then beaten to death by a group of soldiers he had been attempting to shoot at.[42][43]

The joint funeral of McCann, Farrell and Savage took place on 16 March at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) agreed to maintain a minimal presence at the funeral in exchange for guarantees from the families that there would be no salute by masked gunmen.[44] This agreement was leaked to Michael Stone, who described himself as a "freelance Loyalist paramilitary".[45] During the burial, Stone threw grenades into the crowd and began shooting with an automatic pistol, injuring 60 people. Several mourners chased Stone, throwing rocks and shouting abuse. Stone continued shooting and throwing grenades at his pursuers, killing three of them. He was eventually captured after being chased onto a road and the pursuers beat him until the RUC arrived to extract and arrest him.[46][47][48][49]

The funeral of Caoimhín Mac Brádaigh (Kevin Brady), the third and last of the Milltown attack victims to be buried, was scheduled for 19 March.[50] As his cortège proceeded along Andersontown Road, a car driven by two undercover British Army corporals, David Howes and Derek Wood, sped past stewards and drove into the path of the cortège. The corporals attempted to reverse, but were blocked in and a hostile crowd surrounded their car.[51] As members of the crowd began to break into the vehicle, one of the corporals drew and fired a pistol, which momentarily subdued the crowd, before both men were dragged from the car, beaten and disarmed. A local priest intervened to stop the beating, but was pulled away when a military identity card was found, raising speculation that the corporals were SAS members. The two were bundled into a taxi, driven to waste ground by IRA members and beaten further. Six men were seen leaving the vehicle.[52] Another IRA man arrived with a pistol taken from one of the soldiers, with which he repeatedly shot the corporals before handing the weapon to another man, who shot the corporals' bodies multiple times. Margaret Thatcher described the corporals' killings as the "single most horrifying event in Northern Ireland" during her premiership.[53]

The corporals' shootings sparked the largest criminal investigation in Northern Ireland's history, which created fresh tension in Belfast as republicans saw what they believed was a disparity in the efforts the RUC expended in investigating the corporals' murders compared with those of republican civilians. Over four years, more than 200 people were arrested in connection with the killings, of whom 41 were charged with a variety of offences. The first of the so-named Casement Trials concluded quickly; two men were found guilty of murder and given life sentences in the face of overwhelming evidence. Of the trials that followed, many proved much more controversial.[54]

"Death on the Rock"

On 28 April 1988, almost two months after the Gibraltar shootings, ITV broadcast an episode of its current affairs series This Week, titled "Death on the Rock". This Week sent three journalists to investigate the circumstances surrounding the shootings in Spain and Gibraltar. Using eyewitness accounts, and with the cooperation of the Spanish authorities, the documentary reconstructed the events leading up to the shootings; the Spanish police assisted in the reconstruction of the surveillance operation mounted against the IRA members in the weeks before 6 March, and the journalists hired a helicopter to film the route.[55][56] In Gibraltar, they located several new eyewitnesses to the shootings, who each said they had seen McCann, Savage, and Farrell shot without warning or shot after they had fallen to the ground; most agreed to be filmed and provided signed statements. One witness, Kenneth Asquez, provided two near-identical statements through intermediaries, but refused to meet with the journalists or sign either statement. The journalists eventually incorporated his account of seeing Savage shot while on the ground into the programme.[57]

For technical advice, the journalists engaged Lieutenant Colonel George Styles, a retired British Army officer who was regarded as an expert in explosives and ballistics. Styles believed that it would have been obvious to the authorities that Savage's car did not contain a bomb as the weight would have been evident on the vehicle's springs; he also believed that a remote detonator could not have reached the car park from the scenes of the shootings given the number of buildings and other obstacles between the locations.[58] The government refused to comment on the shootings until the inquest, so the documentary concluded by putting its evidence to a leading human rights lawyer, who opined that a judicial inquiry was necessary to establish the facts surrounding the shootings.[59]

Two days before the programme was scheduled for broadcast, Sir Geoffrey Howe telephoned the chairman of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) to request that the authority delay the broadcast until after the inquest on the grounds that it risked prejudicing the proceedings. After viewing the programme and taking legal advice, the IBA decided on the morning of 28 April that "Death on the Rock" should be broadcast as scheduled. Howe made further representation that the documentary would be in contempt of the inquest, but the IBA upheld its decision.[60]

The programme was broadcast at 9pm on 28 April and attracted considerable controversy. The following morning, the British tabloid newspapers lambasted the programme, describing it as a "slur" on the SAS and "trial by television";[61] several criticised the IBA for allowing the documentary to be broadcast.[62] Over the following weeks, newspapers repeatedly printed stories about the documentary's witnesses, in particular Carmen Proetta, who reported seeing McCann and Farrell shot without warning by soldiers who arrived in a Gibraltar Police car. Proetta sued several newspapers for libel and won substantial damages.[63][64] The Sunday Times conducted its own investigation and reported that "Death on the Rock" had misrepresented the views of its witnesses; those involved later complained to other newspapers that The Sunday Times had distorted their comments.[65]

Inquest

Unusually for Gibraltar, there was a long delay between the shootings and the setting of a date for the inquest (the usual method for investigating sudden or controversial deaths in parts of the United Kingdom and its territories); eight weeks after the shootings, the coroner, Felix Pizzarello, announced that the inquest would begin on 27 June 1988. Two weeks later (unknown to Pizzarello), Margaret Thatcher's press secretary announced that the inquest had been indefinitely postponed.[66][67]

The inquest began on 6 September.[68] Pizzarello presided over the proceedings, while eleven jurors evaluated the evidence; representing the Gibraltar government was Eric Thislewaite, the Gibraltar attorney general. The interested parties were represented by John Laws, QC (for the British government), Michael Hucker (for the SAS personnel), and Patrick McGrory (for the families of McCann, Farrell, and Savage). Inquests are non-adversarial proceedings aimed at investigating the circumstances of a death; the investigation is conducted by the coroner, while the representatives of interested parties can cross-examine witnesses. Where the death occurred through the deliberate action of another person, the jury can return a verdict of "lawful killing", "unlawful killing", or an "open verdict"; though inquests cannot apportion blame, in the case of a verdict of unlawful killing the authorities will consider whether any prosecutions should be brought.[69][70]

The soldiers and MI5 officers gave their evidence anonymously and from behind a screen. As the inquest began, observers including Amnesty International expressed concern that McGrory was at a disadvantage, as all of the other lawyers were privy to the evidence of the SAS and MI5 personnel before it was given. The cost of the transcript for each day's proceedings was increased ten-fold the day before the inquest began.[69][70] The inquest heard from 79 witnesses, including police, MI5, and SAS soldiers as well as technical experts and eyewitnesses.[71]

Police, military, and MI5 witnesses

The first witnesses to testify were Gibraltar Police officers. Following them was "Mr O", the senior MI5 officer in charge of Operation Flavius. "O" told the inquest that, in January 1988, Belgian authorities found a car being used by IRA operatives in Brussels. In the car were found a quantity of Semtex, detonators, and equipment for a radio detonation device, which led MI5 to the conclusion that the IRA might use a similar device for the planned attack in Gibraltar. MI5 believed that the IRA had been unlikely to use a "blocking car" (an empty vehicle used to hold a parking space until the bombers bring in the vehicle containing the explosives) as this entailed the added risk of multiple border crossings.[72][73] "O" told the coroner that McCann, Savage, and Farrell had been observed by Spanish authorities arriving at Málaga Airport but had been lost shortly afterwards and were not detected crossing into Gibraltar.[71][74]

Canepa told the inquest that (contrary to McGrory's assertions) there had been no conspiracy to kill McCann, Savage, and Farrell. He stated that, upon learning of the IRA plot from MI5, he set up an advisory committee consisting of MI5, military, and police personnel. As events developed, the committee decided that the Gibraltar Police was not adequately equipped to counter the IRA threat, and Canepa requested assistance from London. The commissioner gave assurances that he had been in command of the operation against the IRA at all times, except for the 25 minutes of the military operation.[note 2] In his cross-examination, McGrory queried the level of control the commissioner had over the operation; he extracted from Canepa that the commissioner had not requested assistance from the SAS specifically. Canepa agreed with "O" that the Spanish police had lost track of the IRA team, and that Savage's arrival in Gibraltar took the authorities by surprise. Although a police officer was stationed in an observation post at the border with instructions for alerting other officers to the arrival of the IRA team, Canepa told the inquest that the officer had been looking for the three IRA members arriving at once. He told McGrory he was "unsure" whether or not the officer had the details of the false passports the trio were travelling under.[76]

The officer from the observation post denied knowing the pseudonyms under which the IRA members were travelling. On cross-examination, he acknowledged having been provided with the pseudonyms at a briefing the night before the shootings. Detective Chief Inspector Joseph Ullger, head of the Gibraltar Police Special Branch, told the coroner that the Spanish border guards had let Savage through out of carelessness, while the regular border officials on the Gibraltar side had not been told to look for the IRA team.[77][78]

"Soldier F", a British Army colonel who was in command of the SAS detachment, testified next,[79] followed by "Soldier E", a more junior officer who was directly responsible for the soldiers.[80] The inquest then heard from the soldiers involved. The SAS personnel all told the coroner that they had been briefed to expect the would-be bombers to be in possession of a remote detonator, and that they had been told that Savage's car definitely contained a bomb. Each soldier testified that the IRA team made movements which the soldiers believed to be threatening, and this prompted them to open fire. McGrory asked about the SAS's policy on lethal force during cross-examination; he asked "Soldier D" about allegations that Savage was shot while on the ground, something "D" strenuously denied, though he stated that he had intended to continue shooting Savage until he was dead.[81][82]

Several Gibraltar Police officers gave evidence about the aftermath of the shootings and the subsequent police investigation. Immediately after the shootings, the soldiers' shell casings were removed from the scene (making it difficult to assess where the soldiers were standing when they fired); two Gibraltar Police officers testified to collecting the casings, one for fear that they might be stolen and the other on the orders of a superior.[83] Other witnesses revealed that the Gibraltar Police had lost evidence and that the soldiers did not give statements to the police until over a week after the shootings.[84]

Civilian witnesses

One of the first civilian witnesses was Allen Feraday, the principal scientific officer at the Royal Armaments Research and Development Establishment. He suggested that a remote detonator could reach from the scenes of the shootings to the car park in which Savage had left the white Renault and beyond. On cross-examination, he stated that the aerial on the Renault was not the type he would expect to be used for receiving a detonation signal and that the IRA had not been known to use a remote-detonated bomb without a line of sight to their target. The following day, "Soldier G" told the coroner that he was not an explosives expert,[85] and that his assessment of Savage's car was based on his belief that the vehicle's aerial looked "too new". McGrory called Dr Michael Scott, an expert in radio-controlled detonation, who disagreed with government witnesses that a bomb at the assembly area could have been detonated from the petrol station, having conducted tests prior to testifying. The government responded by commissioning its own tests, which showed that radio communication between the petrol station and the car park was possible, but not guaranteed.[86]

Professor Alan Watson, a British forensic pathologist, carried out a post-mortem examination of the bodies. Watson arrived in Gibraltar the day after the shootings, by which time the bodies had been taken to the Royal Navy Hospital; he found that the bodies had been stripped of their clothing (causing difficulties in distinguishing entry and exit wounds), that the mortuary had no X-ray machine (which would have allowed Watson to track the paths of the bullets through the bodies), and that he was refused access to any other X-ray machine. After the professor returned to his home in Scotland, he was refused access to the results of blood tests and other evidence which had been sent for analysis and was dissatisfied with the photographs taken by the Gibraltar Police photographer who had assisted him.[87][88][89] At the inquest, McGrory questioned the lack of assistance given to the pathologist, which Watson told him was "a puzzle".[90]

Watson concluded that McCann had been shot four times—once in the jaw (possibly a ricochet), once in the head, and twice in the back; Farrell was shot five times (twice in the face and three times in the back). Watson was unable to determine exactly how many times Savage was shot—he estimated that it was possibly as many as eighteen times. Watson agreed with McGrory's characterisation that Savage's body was "riddled with bullets", stating "I concur with your word. Like a frenzied attack", a statement which made headlines the following morning.[91][92][93] Watson suggested that the deceased were shot while on the ground;[94] a second pathologist called by McGrory offered similar findings. Two weeks later, the court heard from David Pryor—a forensic scientist working for London's Metropolitan Police—who had analysed the IRA members' clothes. His analysis was hampered by the condition of the clothing. Pryor offered evidence which contradicted Soldiers "A" and "B" about their proximity to McCann and Farrell when they opened fire—the soldiers claimed they were at least six feet (1.8 metres) away, but Pryor's analysis was that McCann and Farrell were shot from a distance of no more than two or three feet (0.6 or 0.9 metres).[95]

Several eyewitnesses gave evidence. Three witnessed parts of the shootings and gave accounts which supported the official version of events—in particular, they did not witness the SAS shooting any of the suspects while they were on the floor.[96] Witnesses from "Death on the Rock" also appeared—Stephen Bullock repeated his account of seeing McCann and Savage raise their hands before the SAS shot them; Josie Celecia repeated her account of seeing a soldier shooting at McCann and Farrell while the pair were on the ground. Hucker pointed out that parts of Celecia's testimony had changed since she spoke to "Death on the Rock", and suggested that the gunfire she heard was from the shooting of Savage rather than sustained shooting of McCann and Farrell while they were on the ground, a suggestion Celecia rejected. The SAS's lawyer observed that she was unable to identify the military personnel in photographs her husband had taken.[97][98] Maxie Proetta told the coroner that he had witnessed four men (three in plain clothes and one uniformed Gibraltar Police officer) arriving opposite the petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue; the men jumped over the central reservation barrier and Farrell put her hands up, after which he heard a series of shots. In contrast to his wife's testimony, he believed that Farrell's gesture was one of self-defence rather than surrender, and he believed that the shots he heard did not come from the men from the police car. The government lawyers suggested that the police car was driven by Inspector Revagliatte and carrying four uniformed police officers, but Proetta was adamant that the lawyers' version did not make sense. His wife gave evidence the following day. Contrary to her statement to "Death on the Rock", Carmen Proetta was no longer certain that she had seen McCann and Farrell shot while on the ground. The government lawyers questioned the reliability of Proetta's evidence based on her changes, and implied that she behaved suspiciously by giving evidence to "Death on the Rock" before the police. She responded that the police had not spoken to her about the shootings until after "Death on the Rock" had been shown.[99]

Asquez, who provided an unsworn statement to the "Death on the Rock" team through an intermediary, reluctantly appeared. He retracted his statements to "Death on the Rock", which he claimed he had made up after "pestering" from Major Bob Randall (another "Death on the Rock" witness, who had sold the programme a video recording of the aftermath of the shootings).[note 3] The British media covered Asquez's retraction extensively, while several members of parliament accused Asquez of lying for the television (and "Death on the Rock" of encouraging him) in an attempt to discredit the SAS and the British government. Asquez could not explain why his original statement mentioned the Soldiers "C" and "D" donning berets, showing identity cards, and telling members of the public "it's okay, it's the police" after shooting Savage (details which were not public before the inquest).[101][102]

Verdict

The inquest concluded on 30 September, and Laws and McGrory made their submissions to the coroner regarding the instructions he should give to the jury (Hucker allowed Laws to speak on his behalf). Laws asked the coroner to instruct the jury not to return a verdict of "unlawful killing" on the grounds that there had been a conspiracy to murder the IRA operatives. He allowed for the possibility that the SAS personnel had individually acted unlawfully.[103] McGrory, on the other hand, asked the coroner to allow for the possibility that the British government had conspired to murder McCann, Savage, and Farrell, which he believed was evidenced by the decision to use the SAS for Operation Flavius. The decision, according to McGrory was

wholly unreasonable and led to a lot of what happened afterwards ... it started a whole chain of unreasonable decisions which led to the three killings, which I submit were unlawful and criminal killings.

When the coroner asked McGrory to clarify whether he believed there had been a conspiracy to murder the IRA operatives, he responded

that the choice of the SAS is of great significance ... If the killing of the ASU was, in fact, contemplated by those who chose the SAS, as an act of counter-terror or vengeance, that steps outside the rule of law and it was murder ... and that is a matter for the jury to consider.[104][105]

Pizzarello then summarised the evidence for the jury and instructed them that they could return a verdict of unlawful killing under any of five circumstances, including if they were satisfied that there had been a conspiracy within the British government to murder the three suspected terrorists. He also urged the jury to return a conclusive verdict, rather than the "ambiguity" of an open verdict, and forbade them to make recommendations or add a rider.[106][107][108] By a majority of nine to two, they returned a verdict of lawful killing.[106][108][109]

Six weeks after the inquest, a Gibraltar Police operations order was leaked. The document listed Inspector Revagliatte as the commander of two police firearms teams assigned to the operation.[110] In February 1989, British journalists discovered that the IRA team operating in Spain must have contained more members than the three killed in Gibraltar. The staff at the agencies from which the team rented their vehicles gave the Spanish police descriptions which did not match McCann, Savage, or Farrell and Savage's car was rented several hours before he arrived in Spain.[111]

It emerged that the Spanish authorities knew where McCann and Savage were staying. A senior Spanish police officer repeatedly told journalists that the IRA cell had been under surveillance throughout their time in Spain, and that the Spanish told the British authorities that they did not believe that the three were in possession of a bomb on 6 March. Although the Spanish government did not comment, it honoured 22 police officers involved in the operation at a secret awards ceremony in December 1988, and a Spanish government minister told a press conference in March 1989 that "we followed the terrorists. They were completely under our control".[112] The same month, a journalist discovered that the Spanish side of the operation was conducted by the Foreign Intelligence Brigade rather than the local police as the British government had suggested.[113][114] The Independent and Private Eye conjectured as to the reason for the Spanish government's silence—in 1988, Spain was attempting to join the Western European Union, but was opposed by Britain; the papers' theory was that Margaret Thatcher's government dropped its opposition in exchange for the Spanish government's silence.[115][116]

Legal proceedings

In March 1990 the McCann, Savage, and Farrell families began proceedings against the British government at the High Court in London. The case was dismissed on the grounds that Gibraltar was outside the court's jurisdiction.[117] The families launched an appeal, but withdrew it in the belief that it had no prospect of success.[71] They then applied to the European Commission of Human Rights for an opinion on whether the authorities' actions in Gibraltar violated Article 2 (the "right to life") of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).[118] Issuing its report in April 1993, the commission criticised the conduct of the operation, but found that there had been no violation of Article 2. Nevertheless, the commission referred the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for a final decision.[118][119]

The British government submitted that the killings were "absolutely necessary", within the meaning of Article 2, paragraph 2, to protect the people of Gibraltar from unlawful violence. They stated that the soldiers who carried out the shootings believed that McCann, Savage, and Farrell were capable of detonating a car bomb by remote control. The families alleged that the government had conspired to kill the three; that the planning and control of the operation was flawed; that the inquest was not adequately equipped to investigate the killings; and that the applicable laws of Gibraltar were not compliant with Article 2. The court found that the soldiers' "reflex action" in resorting to lethal force was excessive, but that the soldiers' actions did not, in their own right, give rise to a violation of Article 2. The court held that the soldiers' use of force based on an honestly held belief could be justified, even if that belief was mistaken. To hold otherwise would, in the court's opinion, place too great a burden on law-enforcement personnel. It also dismissed all other allegations, except that regarding the planning and control of the operation. In that respect, the court found that the authorities' failure to arrest the suspects as they crossed the border or earlier, combined with the information that was passed to the soldiers, rendered the use of lethal force almost inevitable. Thus, the court decided there had been a violation of Article 2 in the control of the operation.[120][121]

As the suspects had been killed while preparing an act of terrorism, the court rejected the families' claims for damages, as well as their claim for expenses incurred at the inquest. The court did order the British government to pay the applicants' costs incurred during the proceedings in Strasbourg. The government initially suggested it would not pay, and there was discussion in parliament of the UK withdrawing from the ECHR. It paid the costs on 24 December 1995, within days of the three-month deadline which had been set by the court.[118]

Long-term impact

A history of the Gibraltar Police described Operation Flavius as "the most controversial and violent event" in the history of the force,[122] while the journalist Nicholas Eckert described the incident as "one of the great controversies of the Troubles" and the academic Richard English posited that the "awful sequence of interwoven deaths" was one of the conflict's "most strikingly memorable and shocking periods".[123][124] The explosives the IRA intended to use in Gibraltar were believed to have come from Libya, which was known to be supplying arms to the IRA in the 1980s; some sources speculated that Gibraltar was chosen for its relative proximity to Libya, and the targeting of the territory was intended as a gesture of gratitude to Gaddafi.[6][125][126][127][128]

Several commentators, including Father Raymond Murray, a Catholic priest and author of several books on the Troubles, took the shootings as evidence that the British authorities pursued a "shoot-to-kill" policy against the IRA, and that they intentionally used lethal force in preference to arresting suspected IRA members.[129] Maurice Punch, an academic specialising in policing and civil liberties, described the ECtHR verdict as "a landmark case with important implications" for the control of police operations involving firearms.[15] According to Punch, the significance of the ECtHR judgement was that it placed accountability for the failures in the operation with its commanders, rather than with the soldiers who carried out the shooting. Punch believed that the ruling demonstrated that operations intended to arrest suspects should be conducted by civilian police officers, rather than soldiers.[130] The case is considered a landmark in cases concerning Article 2, particularly in upholding the principle that Article 2, paragraph 2, defines circumstances in which it is permissible to use force which may result in a person's death as an unintended consequence, rather than circumstances in which it is permissible to intentionally deprive a person of their life. It has been cited in later ECtHR cases concerning the use of lethal force by police.[131]

After the inquest verdict, the Governor of Gibraltar, Air Chief Marshal Sir Peter Terry declared "Even in this remote place, there is no place for terrorists." In apparent revenge for his role in Operation Flavius, Terry and his wife were shot and seriously injured when the IRA attacked their home in Staffordshire two years later, in September 1990.[132][133][134][135]

Following Asquez's retraction of his statement to "Death on the Rock" and his allegation that he was pressured into giving a false account of the events he witnessed, the IBA contacted Thames Television to express its concern and to raise the possibility of an investigation into the making of the documentary. Thames eventually agreed to commission an independent inquiry (the first such inquiry into an individual programme), to be conducted by two people with no connection to either Thames or the IBA; Thames engaged Lord Windlesham and Richard Rampton, QC to conduct the investigation.[136] In their report, published in January 1989, Windlesham and Rampton levelled several criticisms at "Death on the Rock", but found it to be a "trenchant" piece of work made in "good faith and without ulterior motives".[137] In conclusion, the authors believed that "Death on the Rock" proved "freedom of expression can prevail in the most extensive, and the most immediate, of all the means of mass communication".[30][137]

See also

- Deal barracks bombing, another IRA attack targeting a military band

- Police use of firearms in the United Kingdom

- Shoot-to-kill policy in Northern Ireland

Notes

- ↑ For security, the SAS, MI5, and Gibraltar Police Special Branch personnel involved in the operation were not named, and were identified by letters of the alphabet in subsequent proceedings.[18]

- ↑ The SAS officers testified that they were briefly handed control twice earlier (at 15:00 and 15:25); Canepa's deputy commissioner stated that he was unaware of either event.[75]

- ↑ Randall was on holiday abroad at the time of the inquest, having been advised by the Gibraltar Police that he would not be needed. Upon his return, he strongly denied putting any pressure on Asquez.[100]

References

Bibliography

- Baldachino, Cecilia; Benady, Tito (2005). The Royal Gibraltar Police: 1830–2005. Gibraltar: Gibraltar Books. ISBN 9781919657127.

- Bishop, Patrick; Mallie, Eamonn (1988). The Provisional IRA. London: Corgi. ISBN 9780552133371.

- Bolton, Roger (1990). Death on the Rock and Other Stories. London: W. H. Allen. ISBN 9781852271633.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). The IRA (5th ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312294168.

- Crawshaw, Ralph; Holmström, Leif (2006). Essential Cases on Human Rights for the Police. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9789004139787.

- Dillon, Martin (1992). Stone Cold: The True Story of Michael Stone and the Milltown Massacre. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9781448185139.

- Eckert, Nicholas (1999). Fatal Encounter: The Story of the Gibraltar Killings. Dublin: Poolbeg. ISBN 9781853718373.

- English, Richard (2012). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (revised ed.). London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 9781447212492.

- Morgan, Michael; Leggett, Susan (1996). Mainstream(s) and Margins: Cultural Politics in the 90s. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313297960.

- Murray, Raymond (2004) [1990]. The SAS in Ireland (Revised ed.). Dublin: Mercier Press. ISBN 9781856354370.

- O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815605973.

- O'Leary, Brendan (2007). Heiberg, Marianne; O'Leary, Brendan; Tirman, John (eds.). The IRA: Looking Back; Mission Accomplished?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812239744.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Punch, Maurice (2011). Shoot to Kill: Police Accountability and Fatal Force. Bristol: Policy Press. ISBN 9781847424723.

- Urban, Mark (1992). Big Boys' Rules: The Secret Struggle Against the IRA. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571168095.

- Waddington, P. A. J. (1991). The Strong Arm of the Law: Armed and Public Order Policing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198273592.

- Williams, Maxine (1989). Murder on the Rock: How the British Government Got Away with Murder. London: Larkin Publications. ISBN 9780905400105.

- Windlesham, Lord (David); Rampton, Richard, QC (1989). The Windlesham-Rampton Report on "Death on the Rock". London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571141500.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Citations

- ↑ "Gibraltar killings and release of the Guildford Four". BBC News. 18 March 1999. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ McKittrick, David (6 June 1994). "Dangers that justified Gibraltar killings". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Bishop & Mallie, pp. 136–138.

- ↑ Coogan, pp. 375–376, 379.

- ↑ O'Leary, pp. 210–211.

- 1 2 3 O'Brien, p. 151.

- ↑ Crawshaw & Holmström, p. 88.

- ↑ English, p. 257.

- ↑ Urban, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Urban, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 398–399.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 56–62.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 63.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 Punch, p. 15.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 70.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 171.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 73–77.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 78.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Punch, p. 104.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 149.

- ↑ Waddington, p. 88.

- 1 2 Eckert, p. 83.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 81–86.

- ↑ Crawshaw & Holmström, p. 92.

- 1 2 English, p. 256.

- 1 2 Eckert, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Williams, p. 33.

- 1 2 Morgan & Leggett, pp. 145–148.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 88.

- ↑ Murray, p. 400.

- ↑ Morgan & Leggett, pp. 150, 152.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 86.

- ↑ Murray, p. 399.

- ↑ "Haughey didn't want IRA bodies from Gibraltar in Dublin". RTÉ.ie. 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 93.

- 1 2 Murray, p. 428.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 92.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 94.

- ↑ Dillon, p. 145.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 96–99.

- ↑ Dillon, pp. 143–159.

- ↑ O'Brien, p. 164.

- ↑ Murray, p. 429.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 103.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 112–114.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 116, 151.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 128.

- ↑ Murray, p. 404,

- ↑ Eckert pp. 127–130.

- ↑ Eckert p. 124.

- ↑ Eckert p. 131.

- ↑ Windlesham & Rampton, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Eckert p. 138.

- ↑ Williams, p. 38.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Murray, p. 418.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 163.

- ↑ Williams, p. 10.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 166.

- 1 2 Eckert, pp. 169–171.

- 1 2 Williams, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Crawshaw & Holmström, p. 93.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 176–178.

- ↑ Murray, p. 406.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 181, 194.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 181–183.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 183–186.

- ↑ Williams, p. 13.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 187–191.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 414–416.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 196–198.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 201.

- ↑ Crawshaw & Holmström, p. 89.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 215–220.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Williams, p. 43.

- ↑ Murray, p. 418.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 202.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 203.

- ↑ Waddington, p. 94.

- ↑ Murray, p. 419.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 206.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 223.

- ↑ Murray, p. 417.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 232.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 421–422.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 234.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 412–413

- 1 2 Eckert, p. 235.

- ↑ Bolton, p. 268.

- 1 2 Williams, p. 42.

- ↑ Murray, p. 434.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 258

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 258–261.

- ↑ Wiliams, p. 17.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 256.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 284.

- 1 2 3 Eckert, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Crawshaw & Holmström, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Crawshaw & Holmström, pp. 97–104.

- ↑ Punch, p. 17.

- ↑ Baldachino & Benady, p. 71.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 69.

- ↑ English, p. 258.

- ↑ Urban, p. 209.

- ↑ Dillon, p. 142.

- ↑ Morgan & Leggett, p. 147.

- ↑ Eckert, p. 270.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 464–465.

- ↑ Punch, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Punch, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Mills, Heather (28 September 1995). "Sudden death and the long quest for answers". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Rule, Sheila (20 September 1990). "I.R.A. raid wounds an ex-British aide". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Eckert, pp. 281–282.

- ↑ Murray, pp. 49

- ↑ Windlesham & Rampton, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 Windlesham & Rampton, pp. 144–145