Georges Lemaître RAS Associate | |

|---|---|

Lemaître in 1933 | |

| Born | Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître 17 July 1894 Charleroi, Belgium |

| Died | 20 June 1966 (aged 71) Leuven, Belgium |

| Alma mater | Catholic University of Louvain St Edmund's House, Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Known for | Theory of the expansion of the universe Big Bang theory Hubble–Lemaître law Lemaître–Tolman metric Lemaître coordinates Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric |

| Awards | Francqui Prize (1934) Eddington Medal (1953) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cosmology Astrophysics Mathematics |

| Institutions | Catholic University of Leuven Catholic University of America |

| Doctoral advisor | Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin (Leuven) |

| Other academic advisors | Arthur Eddington (Cambridge) Harlow Shapley (MIT) |

| Ecclesiastical career | |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Ordained | 22 September 1923 by Désiré-Joseph Mercier |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître (/ləˈmɛtrə/ lə-MET-rə; French: [ʒɔʁʒ ləmɛːtʁ] ⓘ; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain.[1] He was the first to theorize that the recession of nearby galaxies can be explained by an expanding universe,[2] which was observationally confirmed soon afterwards by Edwin Hubble.[3][4] He first derived "Hubble's law", now called the Hubble–Lemaître law by the IAU,[5][6] and published the first estimation of the Hubble constant in 1927, two years before Hubble's article.[7][8][3][4] Lemaître also proposed the "Big Bang theory" of the origin of the universe, calling it the "hypothesis of the primeval atom",[9] and later calling it "the beginning of the world".[10]

Early life

Lemaître was born in Charleroi, Belgium, the eldest of four children. His father Joseph Lemaître was a prosperous industrial weaver and his mother was Marguerite, née Lannoy.[11] After a classical education at a Jesuit secondary school, the Collège du Sacré-Cœur, in Charleroi, in Belgium, he began studying civil engineering at the Catholic University of Louvain at the age of 17. In 1914, he interrupted his studies to serve as an artillery officer in the Belgian army for the duration of World War I. At the end of hostilities, he received the Belgian War Cross with palms.[12]

After the war, he studied physics and mathematics, and began to prepare for the diocesan priesthood, not for the Jesuits.[13] He obtained his doctorate in 1920 with a thesis entitled l'Approximation des fonctions de plusieurs variables réelles (Approximation of functions of several real variables), written under the direction of Charles de la Vallée-Poussin.[14] He was ordained as a priest on 22 September 1923 by Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier.[15][16]

In 1923, he became a research associate in astronomy at the University of Cambridge, spending a year at St Edmund's House (now St Edmund's College, University of Cambridge). There he worked with Arthur Eddington,[17][18] a Quaker and physicist who introduced him to modern cosmology, stellar astronomy, and numerical analysis. He spent the next year at Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with Harlow Shapley, who had just gained renown for his work on nebulae, and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he registered for the doctoral program in the sciences.

Career

On his return to Belgium in 1925, he became a part-time lecturer at the Catholic University of Louvain and began the report that was published in 1927 in the Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels) under the title "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques" ("A homogeneous Universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae"), that was later to bring him international fame.[2] In this report, he presented the new idea that the universe is expanding, which he derived from General Relativity. This idea later became known as Hubble's law, even though Lemaître was the first to provide an observational estimate of the Hubble constant.[19] The initial state he proposed was taken to be Einstein's own model of a finitely sized static universe. The paper had little impact because the journal in which it was published was not widely read by astronomers outside Belgium. Arthur Eddington reportedly helped translate the article into English in 1931, but the part of it pertaining to the estimation of the "Hubble constant" was not included in the translation for reasons that remained unknown for a long time.[20] This issue was clarified in 2011 by Mario Livio: Lemaître omitted those paragraphs himself when translating the paper for the Royal Astronomical Society, in favour of reports of newer work on the subject, since by that time Hubble's calculations had already improved on Lemaître's earlier ones.[4]

At this time, Einstein, while not taking exception to the mathematics of Lemaître's theory, refused to accept that the universe was expanding; Lemaître recalled his commenting "Vos calculs sont corrects, mais votre physique est abominable"[21] ("Your calculations are correct, but your physics is atrocious"). In the same year, Lemaître returned to MIT to present his doctoral thesis on The gravitational field in a fluid sphere of uniform invariant density according to the theory of relativity.[22] Upon obtaining his Ph.D., he was named ordinary professor at the Catholic University of Louvain.

In 1931, Arthur Eddington published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society a long commentary on Lemaître's 1927 article, which Eddington described as a "brilliant solution" to the outstanding problems of cosmology.[23] The original paper was published in an abbreviated English translation later on in 1931, along with a sequel by Lemaître responding to Eddington's comments.[24] Lemaître was then invited to London to participate in a meeting of the British Association on the relation between the physical universe and spirituality. There he proposed that the universe expanded from an initial point, which he called the "Primeval Atom". He developed this idea in a report published in Nature.[10] Lemaître's theory appeared for the first time in an article for the general reader on science and technology subjects in the December 1932 issue of Popular Science.[25] Lemaître's theory became better known as the "Big Bang theory," a picturesque term playfully coined during a 1949 BBC radio broadcast by the astronomer Fred Hoyle,[26][27] who was a proponent of the steady state universe and remained so until his death in 2001.

Lemaître's proposal met with skepticism from his fellow scientists. Eddington found Lemaître's notion unpleasant.[28] Einstein thought it unjustifiable from a physical point of view, although he encouraged Lemaître to look into the possibility of models of non-isotropic expansion, so it is clear he was not altogether dismissive of the concept. Einstein also appreciated Lemaître's argument that Einstein's model of a static universe could not be sustained into the infinite past.

With Manuel Sandoval Vallarta, Lemaître discovered that the intensity of cosmic rays varied with latitude because these charged particles are interacting with the Earth's magnetic field.[29] In their calculations, Lemaître and Vallarta made use of MIT's differential analyzer computer developed by Vannevar Bush. They also worked on a theory of primary cosmic radiation and applied it to their investigations of the Sun's magnetic field and the effects of the galaxy's rotation.

Lemaître and Einstein met on four occasions: in 1927 in Brussels, at the time of a Solvay Conference; in 1932 in Belgium, at the time of a cycle of conferences in Brussels; in California in January 1933;[30] and in 1935 at Princeton. In 1933 at the California Institute of Technology, after Lemaître detailed his theory, Einstein stood up, applauded, and is supposed to have said, "This is the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of creation to which I have ever listened."[31] However, there is disagreement over the reporting of this quote in the newspapers of the time, and it may be that Einstein was not referring to the theory as a whole, but only to Lemaître's proposal that cosmic rays may be the leftover artifacts of the initial "explosion".

In 1933, when he resumed his theory of the expanding universe and published a more detailed version in the Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels, Lemaître achieved his greatest public recognition.[32] Newspapers around the world called him a famous Belgian scientist and described him as the leader of new cosmological physics. Also in 1933, Lemaître served as a visiting professor at The Catholic University of America.[33]

On July 27, 1935, he was named an honorary canon of the Malines cathedral by Cardinal Josef Van Roey.[34]

He was elected a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1936, and took an active role there, serving as its president from March 1960 until his death.[35]

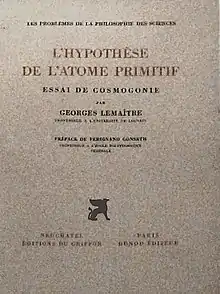

In 1941, he was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Belgium.[36] In 1946, he published his book on L'Hypothèse de l'Atome Primitif (The Primeval Atom Hypothesis). It was translated into Spanish in the same year and into English in 1950.

In relation to Catholic teaching on the origin of the Universe, Lemaître viewed his theory as neutral with neither a connection nor a contradiction of the Faith; as a devoted Catholic priest, Lemaître was opposed to mixing science with religion,[16] although he held that the two fields were not in conflict.[37]

During the 1950s, he gradually gave up part of his teaching workload, ending it completely when he took emeritus status in 1964. In 1962, strongly opposed to the expulsion of French speakers from the Catholic University of Louvain, he created the ACAPSUL movement together with Gérard Garitte to fight against the split.[38]

During the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65 he was asked by Pope John XXIII to serve on the 4th session of the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control.[39] However, since his health made it impossible for him to travel to Rome – he suffered a heart attack in December 1964 – Lemaître demurred, expressing surprise that he was chosen. He told a Dominican colleague, Père Henri de Riedmatten, that he thought it was dangerous for a mathematician to venture outside of his area of expertise.[40] He was also named domestic prelate (Monsignor) in 1960 by Pope John XXIII.[36]

At the end of his life, he was increasingly devoted to problems of numerical calculation. He was a remarkable algebraicist and arithmetical calculator. Since 1930, he had used the most powerful calculating machine of the time, the Mercedes-Euklid. In 1958, he was introduced to the University's Burroughs E 101, its first electronic computer. Lemaître maintained a strong interest in the development of computers and, even more, in the problems of language and computer programming.

He died on 20 June 1966, shortly after having learned of the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, which provided further evidence for his proposal about the birth of the universe.[41]

Work

Lemaître was a pioneer in applying Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity to cosmology. In a 1927 article, which preceded Edwin Hubble's landmark article by two years, Lemaître derived what became known as Hubble's law and proposed it as a generic phenomenon in relativistic cosmology. Lemaître was also the first to estimate the numerical value of the Hubble constant.

Einstein was skeptical of this paper. When Lemaître approached Einstein at the 1927 Solvay Conference, the latter pointed out that Alexander Friedmann had proposed a similar solution to Einstein's equations in 1922, implying that the radius of the universe increased over time. (Einstein had also criticized Friedmann's calculations, but withdrew his comments.) In 1931, his annus mirabilis,[42] Lemaître published an article in Nature setting out his theory of the "primeval atom."[10]

Friedmann was handicapped by living and working in the USSR, and died in 1925, soon after inventing the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric. Because Lemaître spent almost his entire career in Europe, his scientific work is not as well known in the United States as that of Hubble or Einstein, both well known in the U.S. by virtue of residing there. Nevertheless, Lemaître's theory changed the course of cosmology. This was because Lemaître:

- Was well acquainted with the work of astronomers, and designed his theory to have testable implications and to be in accord with observations of the time, in particular to explain the observed redshift of galaxies and the linear relation between distances and velocities;

- Proposed his theory at an opportune time, since Edwin Hubble would soon publish his velocity–distance relation that strongly supported an expanding universe and, consequently, Lemaître's Big Bang theory;

- Had studied under Arthur Eddington, who made sure that Lemaître got a hearing in the scientific community.

Both Friedmann and Lemaître proposed relativistic cosmologies featuring an expanding universe. However, Lemaître was the first to propose that the expansion explains the redshift of galaxies. He further concluded that an initial "creation-like" event must have occurred. In the 1980s, Alan Guth and Andrei Linde modified this theory by adding to it a period of inflation.

Einstein at first dismissed Friedmann, and then (privately) Lemaître, out of hand, saying that not all mathematics lead to correct theories. After Hubble's discovery was published, Einstein quickly and publicly endorsed Lemaître's theory, helping both the theory and its proposer get fast recognition.[43]

Lemaître was also an early adopter of computers for cosmological calculations. He introduced the first computer to his university (a Burroughs E 101) in 1958 and was one of the inventors of the Fast Fourier transform algorithm.[44]

In 1931, Lemaître was the first scientist to propose the expansion of the universe was actually accelerating, which was confirmed observationally in the 1990s through observations of very distant Type IA supernova with the Hubble Space Telescope which led to the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics.[45][46][47]

In 1933, Lemaître found an important inhomogeneous solution of Einstein's field equations describing a spherical dust cloud, the Lemaître–Tolman metric.

In 1948 Lemaître published a polished mathematical essay "Quaternions et espace elliptique" which clarified an obscure space.[48] William Kingdon Clifford had cryptically described elliptic space in 1873 at a time when versors were too common to mention. Lemaître developed the theory of quaternions from first principles so that his essay can stand on its own, but he recalled the Erlangen program in geometry while developing the metric geometry of elliptic space.

Lemaître was the first theoretical cosmologist ever nominated in 1954 for the Nobel Prize in Physics for his prediction of the expanding universe. He was also nominated for the 1956 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his primeval atom theory.[49]

Honours

On 17 March 1934, Lemaître received the Francqui Prize, the highest Belgian scientific distinction, from King Leopold III.[36] His proposers were Albert Einstein, Charles de la Vallée-Poussin and Alexandre de Hemptinne. The members of the international jury were Eddington, Langevin, Théophile de Donder and Marcel Dehalu. The same year he received the Mendel Medal of the Villanova University.[50]

In 1936, Lemaître received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France, the French astronomical society.[51]

Another distinction that the Belgian government reserves for exceptional scientists was allotted to him in 1950: the decennial prize for applied sciences for the period 1933–1942.[36]

Lemaître was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1945.[52]

In 1953, he was given the inaugural Eddington Medal awarded by the Royal Astronomical Society.[53][54]

In 2005, Lemaître was voted to the 61st place of De Grootste Belg ("The Greatest Belgian"), a Flemish television program on the VRT. In the same year he was voted to the 78th place by the audience of the Les plus grands Belges ("The Greatest Belgians"), a television show of the RTBF. Later, in December 2022, VRT recovered in its archives a lost 20-minute interview with Georges Lemaître in 1964, "a gem," says cosmologist Thomas Hertog.[55][56]

On 17 July 2018, Google Doodle celebrated Georges Lemaître's 124th birthday.[57]

On 26 October 2018, an electronic vote among all members of the International Astronomical Union voted 78% to recommend changing the name of the Hubble law to the Hubble–Lemaître law.[6][58]

In popular culture

Namesakes

- The lunar crater Lemaître

- Lemaître coordinates

- Hubble–Lemaître law

- Lemaître observers in the Schwarzschild vacuum frame fields in general relativity

- Minor planet 1565 Lemaître

- The fifth Automated Transfer Vehicle, Georges Lemaître ATV

- Norwegian indie electronic band Lemaitre

- The Maison Georges Lemaître is the main building of the University of Louvain's UCLouvain Charleroi campus, adjacent to Lemaître's birthplace

Bibliography

- G. Lemaître, L'Hypothèse de l'atome primitif. Essai de cosmogonie, Neuchâtel (Switzerland), Editions du Griffon, and Brussels, Editions Hermès, 1946

- G. Lemaître, The Primeval Atom – An Essay on Cosmogony, New York-London, D. Van Nostrand Co, 1950.

- "The Primeval Atom," in Munitz, Milton K., ed., Theories of the Universe, The Free Press, 1957.

- The gravitational field in a fluid sphere of uniform invariant density according, to the theory of relativity ; Note on de Sitter ̕Universe ; Note on the theory of pulsating stars (PDF), Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept. Of Physics, 1927b

- "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques". Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (in French). 47: 49. April 1927. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)- (Translated in: "A Homogeneous Universe of Constant Mass and Increasing Radius Accounting for the Radial Velocity of Extra-galactic Nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91 (5): 483–490. 1931. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L. doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.483.)

- "Expansion of the universe, The expanding universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 490–501. March 1931. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..490L. doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.490.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - "The Beginning of the World from the Point of View of Quantum Theory". Nature. 127 (3210): 706. 9 May 1931. Bibcode:1931Natur.127..706L. doi:10.1038/127706b0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4089233.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - "The Evolution of the Universe: Discussion". Nature. 128 (3234): 699–701. October 1931. Bibcode:1931Natur.128..704L. doi:10.1038/128704a0. S2CID 4028196.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - "Evolution of the Expanding Universe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 20 (1): 12–17. 1934. Bibcode:1934PNAS...20...12L. doi:10.1073/pnas.20.1.12. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1076329. PMID 16587831.

See also

- Cold Big Bang

- List of Roman Catholic cleric-scientists

- List of Christians in science and technology

- Michał Heller – Polish Catholic priest and physicist/astronomer.

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ "Obituary: Georges Lemaitre". Physics Today. 19 (9): 119–121. September 1966. doi:10.1063/1.3048455.

- 1 2 Lemaître 1927a, p. 49.

- 1 2 Reich 2011.

- 1 2 3 Livio 2011, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ "name change for Hubble Law". Nature. 563 (7729): 10–11. 31 October 2018. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07180-9. PMID 30382217. S2CID 256770198.

The International Astronomical Union recommends that the law should now be known as the Hubble–Lemaître law, to pay tribute to the Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître, who derived the speed–distance relationship two years earlier than did US astronomer Edwin Hubble.

- 1 2 "International Astronomical Union members vote to recommend renaming the Hubble law as the Hubble–Lemaître law". iau.org. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ↑ van den Bergh 2011, p. 151.

- ↑ Block 2012, pp. 89–96.

- ↑ "Big bang theory is introduced – 1927". A Science Odyssey. WGBH. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Lemaître 1931b, p. 706.

- ↑ Dominique Lambert, An Atom of the Universe: The Life and Work of Georges Lemaître, Lessius, 2000, p.22

- ↑ "Croix de guerre, reçue en 1918 et la palme en 1921 (Georges Lemaître)". archives.uclouvain.be. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Farrell 2008.

- ↑ "Georges Lemaître - the Mathematics Genealogy Project".

- ↑ Lambert 1996, pp. 309–343.

- 1 2 Lambert 1997, pp. 28–53.

- ↑ Holder, Rodney D.; Mitton, Simon (13 January 2013). Georges Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy. Springer. ISBN 9783642322549.

- ↑ General Relativity Conflict and Rivalries: Einstein's Polemics with Physicists. Cambridge Scholars. 14 January 2016. ISBN 9781443887809.

- ↑ Belenkiy 2012, p. 38.

- ↑ Way & Nussbaumer 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Deprit 1984, p. 370.

- ↑ Lemaître 1927b.

- ↑ Eddington 1930, pp. 668–688.

- ↑ Lemaître 1931a, pp. 490–501.

- ↑ Menzel 1932, p. 52.

- ↑ "Third Programme – 28 March 1949". BBC Genome. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hoyle on the Radio: Creating the 'Big Bang'". Fred Hoyle: An Online Exhibition. St John's College Cambridge. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ Lemaître 1931b, p. 1.

- ↑ Lemaitre, G.; Vallarta, M. S. (15 January 1933). "On Compton's Latitude Effect of Cosmic Radiation". Physical Review. 43 (2): 87–91. Bibcode:1933PhRv...43...87L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.43.87. S2CID 7293355.

- ↑ Lambert n.d.

- ↑ Kragh 1999, p. 55.

- ↑ Lemaître 1934, pp. 12–17.

- ↑ McCarthy Hines, Mary. "Physics Professor Earns Historic Recognition". Catholic U. The Catholic University of America (Spring 2019): 16.

- ↑ "The Faith and Reason of Father George Lemaître". catholicculture.org. February 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ↑ "Georges Lemaitre". Pontifical Academy of Science. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Rapport Jury Mgr Georges Lemaître". Fondation Francqui – Stichting (in French). 1934. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ Crawley, William. 2012. "Father of the Big Bang". BBC.

- ↑ "ACAPSUL – Association du corps académique et du personnel scientifique de l'Université de Louvain".

- ↑ McClory 1998, p. 205.

- ↑ Lambert 2000, p. 302.

- ↑ "Georges Lemaître: Who was the Belgian priest who discovered the universe is expanding?". Independent.co.uk. 16 July 2018.

- ↑ Luminet 2011, pp. 2911–2928.

- ↑ Singh 2010.

- ↑ "Georges Lemaître". uclouvain.be. 2 June 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Longair 2007, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Riess et al. 1998.

- ↑ Steer 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ Georges Lemaître (1948) "Quaternions et espace elliptique", Acta Pontifical Academy of Sciences 12:57–78

- ↑ "Nomination archive". The Nobel Prize. April 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ↑ "Abbé Georges Edouard Etienne Lemaître, Ph.D., D.Sc. – 1934". Villanova University. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Médaille du prix Janssen décernée par la Société Astronomique de France à Georges Lemaître (1936)". Archives.uclouvain.be. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ↑ "Medallists of the Royal Astronomical Society". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 113, p.2

- ↑ De Maeseneer, Wim (31 December 2022). "Lang naar gezocht, eindelijk gevonden: VRT vindt interview uit 1964 terug met de Belg die de oerknal bedacht" [Long sought, finally found: VRT finds 1964 interview with Belgian who invented the Big Bang]. vrtnws.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 January 2023.

VRT has recovered a lost interview with Georges Lemaître in its archives. He was interviewed about it in 1964 for the then BRT, but until recently it was thought that only a short excerpt of it had been preserved. Now the entire 20-minute interview has been recovered. "A gem," says cosmologist Thomas Hertog.

- ↑ Satya Gontcho A Gontcho; Jean-Baptiste Kikwaya Eluo; Gabor, Paul (2023). "Resurfaced 1964 VRT video interview of Georges Lemaître". arXiv:2301.07198 [physics.hist-ph].

- ↑ "Who was Georges Lemaître? Google Doodle celebrates 124th birthday of the astronomer behind the Big Bang Theory". Daily Mirror. 17 July 2018.

- ↑ Gibney 2018.

Sources

- Belenkiy, Ari (2012). "Alexander Friedmann and the origins of modern cosmology". Physics Today. 65 (10): 38. Bibcode:2012PhT....65j..38B. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1750.

- Block, David L. (2012). "Georges Lemaître and Stigler's Law of Eponymy". Georges Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 395. pp. 89–96. arXiv:1106.3928. Bibcode:2012ASSL..395...89B. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32254-9_8. ISBN 978-3-642-32253-2. S2CID 119205665.

- Deprit, A. (1984). "Monsignor Georges Lemaître". In A. Barger (ed.). The Big Bang and Georges Lemaître. Reidel. p. 370.

- Eddington, A. S. (1930). "On the instability of Einstein's spherical world". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 90 (7): 668–688. Bibcode:1930MNRAS..90..668E. doi:10.1093/mnras/90.7.668.

- Evon, Dan (15 May 2019). "Did 56% of Survey Respondents Say 'Arabic Numerals' Shouldn't be Taught in School?". Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- Farrell, John (2005). The Day Without Yesterday: Lemaitre, Einstein, and the Birth of Modern Cosmology. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-660-1.

- Farrell, John (22 March 2008). "The Original Big Bang Man" (PDF). The Tablet. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Gibney, Elizabeth (2018). "Belgian priest recognized in Hubble law name change". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07234-y. S2CID 158098472.

- Holder, Rodney; Mitton, Simon (2013). Georges Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy (Astrophysics and Space Science Library 395). Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-32253-2.

- Kragh, Helge (1999). Cosmology and Controversy: The Historical Development of Two Theories of the Universe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00546-X.

- Lambert, Dominique (n.d.). "Einstein and Lemaître: two friends, two cosmologies…". Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Lambert, Dominique (1996). "Mgr Georges Lemaître et les "Amis de Jésus"". Revue Théologique de Louvain (in French). 27 (3): 309–343. doi:10.3406/thlou.1996.2836. ISSN 0080-2654.

- Lambert, Dominique (1997). "Monseigneur Georges Lemaître et le débat entre la cosmologie et la foi (à suivre)". Revue Théologique de Louvain (in French). 28 (1): 28–53. doi:10.3406/thlou.1997.2867. ISSN 0080-2654.

- Lambert, Dominique (2000). Un Atome d'Univers [The Atom of the Universe] (in French). Lessius.

- Lambert, Dominique (2015). The Atom of the Universe: The Life and Work of Georges Lemaître. Copernicus Center Press. ISBN 978-8378860716.

- Landsberg, Peter T. (1999). Seeking Ultimates: An Intuitive Guide to Physics, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7503-0657-7.

Indeed the attempt in 1951 by Pope Pius XII to look forward to a time when creation would be established by science was resented by several physicists, notably by George Gamow and even George Lemaitre, a member of the Pontifical Academy.

- Livio, Mario (10 November 2011). "Lost in translation: Mystery of the missing text solved". Nature. 479 (7372): 171–173. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..171L. doi:10.1038/479171a. PMID 22071745. S2CID 203468083.

- Longair, Malcolm (2007). The Cosmic Century. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47436-8.

- Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2011). "Editorial note to: Georges Lemaître, The beginning of the world from the point of view of quantum theory". General Relativity and Gravitation. 43 (10): 2911–2928. arXiv:1105.6271. Bibcode:2011GReGr..43.2911L. doi:10.1007/s10714-011-1213-7. ISSN 0001-7701. S2CID 55219897.

- McClory, Robert (1998). "Appendice II: Membres de la Commission". Rome et la contraception: histoire secrète de l'encyclique Humanae vitae (in French). Editions de l'Atelier. p. 205. ISBN 978-2-7082-3342-3.

- Menzel, David (December 1932). "A blast of Giant Atom created our universe". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. p. 52.

- Nussbaumer, Harry; Bieri, Lydia (2009). Discovering the Expanding Universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51484-2.

- Reich, Eugenie Samuel (27 June 2011). "Edwin Hubble in translation trouble". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.385.

- Riess, Adam G.; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Challis, Peter; Clocchiatti, Alejandro; Diercks, Alan; Garnavich, Peter M.; Gilliland, Ron L.; Hogan, Craig J.; Jha, Saurabh; Kirshner, Robert P.; Leibundgut, B.; Phillips, M. M.; Reiss, David; Schmidt, Brian P.; Schommer, Robert A.; Smith, R. Chris; Spyromilio, J.; Stubbs, Christopher; Suntzeff, Nicholas B.; Tonry, John (1998). "Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant". The Astronomical Journal. 116 (3): 1009–1038. arXiv:astro-ph/9805201. Bibcode:1998AJ....116.1009R. doi:10.1086/300499. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 15640044.

- Singh, Simon (2010). Big Bang. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0-00-737550-9.

- Steer, Ian (2013). "Lemaître's Limit". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 107 (2): 57. arXiv:1212.6566. Bibcode:2013JRASC.107...57S. ISSN 0035-872X.

- Soter, Steven; deGrasse Tyson, Neil (2000). "Georges Lemaître, Father of the Big Bang". Cosmic Horizons: Astronomy at the Cutting Edge. American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- van den Bergh, Sidney (6 June 2011). "The Curious Case of Lemaitre's Equation No. 24". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 105 (4): 151. arXiv:1106.1195. Bibcode:2011JRASC.105..151V.

- Way, Michael; Nussbaumer, Harry (2011). "Lemaître's Hubble relationship". Physics Today. 64 (8): 8. arXiv:1104.3031. Bibcode:2011PhT....64h...8W. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1194. S2CID 119270674.

Further reading

- Berenda, Carlton W (1951). "Notes on Lemaître's Cosmogony". The Journal of Philosophy. 48 (10): 338–341. doi:10.2307/2020873. JSTOR 2020873.

- Berger, A.L., editor, The Big Bang and Georges Lemaître: Proceedings of a Symposium in honour of G. Lemaître fifty years after his initiation of Big-Bang Cosmology, Louvain-Ia-Neuve, Belgium, 10–13 October 1983 (Springer, 2013).

- Cevasco, George A (1954). "The Universe and Abbe Lemaitre". Irish Monthly. 83 (969).

- Godart, Odon & Heller, Michal (1985) Cosmology of Lemaître, Pachart Publishing House.

- Farrell, John, The Day Without Yesterday: Lemaître, Einstein and the Birth of Modern Cosmology (Basic Books, 2005), ISBN 978-1560256601.

- McCrea, William H. (1970). "Cosmology Today: A Review of the State of the Science with Particular Emphasis on the Contributions of Georges Lemaître". American Scientist. 58 (5).

- Kragh, Helge (1970). "Georges Lemaître" (PDF). In Gillispie, Charles (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

- Turek, Jósef. Georges Lemaître and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Specola Vaticana, 1989.

- Lost video (1964) of Georges Lemaître, father of the Big Bang theory, recovered, https://phys.org/news/2023-01-lost-video-georges-lematre-father.html