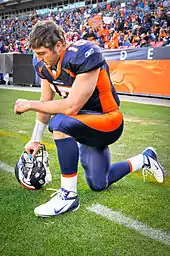

Genuflection or genuflexion is the act of bending a knee to the ground, as distinguished from kneeling which more strictly involves both knees. From early times, it has been a gesture of deep respect for a superior. Today, the gesture is common in the Christian religious practices of the Anglicanism,[1] Lutheranism,[2] the Catholic Church,[3] and Western Rite Orthodoxy.[4] The Latin word genuflectio, from which the English word is derived, originally meant kneeling with both knees rather than the rapid dropping to one knee and immediately rising that became customary in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. It is often referred to as "going down on one knee" or "bowing the knee".[5] In Western culture, one genuflects on the left knee to a human dignitary, whether ecclesiastical or civil, while, in Christian churches and chapels, one genuflects on the right knee when the Sacrament is not exposed but in a tabernacle or veiled (conversely, one kneels with both knees if the Sacrament is exposed).

History

In 328 BC, Alexander the Great introduced into his court-etiquette some form of genuflection already in use in Persia, a modification to the tradition of Proskynesis.[6] In the Byzantine Empire even senators were required to genuflect to the emperor.[7] In medieval Europe, one demonstrated respect for a king or noble by going down on the left knee, often remaining there until told to rise. It is traditionally often performed in western cultures by a man making a proposal of marriage. This is done on the left knee.

The custom of genuflecting, as a sign of respect and even of service, arose out of the honor given to medieval kings. In modern times, when the folded flag of a fallen veteran is offered to the family, the presenting officer will go down on his left knee, if the recipient is seated.[8]

In Christianity

Genuflection, typically on one knee, still plays a part in the Anglican, Lutheran, Roman Catholic and Western Rite Orthodox traditions, among other churches; it is different from kneeling in prayer, which is more widespread.

Those for whom the gesture is difficult, such as the aged or those in poor physical condition, are not expected to perform it. Bowing of the head or at the waist, if possible, are common substitutes.

Except for those people, genuflection is still today mandatory in some situations, such as (in the Catholic Church) when passing in front of the Blessed Sacrament, or during the Consecration in the Mass.

In the King James Version of the Holy Scriptures, the verb "to kneel" occurs more than thirty times, both in the Old and in The New Testament.[9]

In front of the Blessed Sacrament

Genuflection is a sign of reverence to the Blessed Sacrament. Its purpose is to allow the worshipper to engage his whole person in acknowledging the presence of and to honor Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist.[10] It is customary to genuflect whenever one comes into or leaves the presence of the Blessed Sacrament reserved in the Tabernacle. "This venerable practice of genuflecting before the Blessed Sacrament, whether enclosed in the tabernacle or publicly exposed, as a sign of adoration, ...requires that it be performed in a recollected way. In order that the heart may bow before God in profound reverence, the genuflection must be neither hurried nor careless."[11]

Genuflection to the Blessed Sacrament, the consecrated Eucharist, especially when arriving or leaving its presence, is a practice in the Anglicanism,[1] the Latin Church of the Catholic Church,[3] Lutheranism,[2] and Western Rite Orthodoxy.[4] It is a comparatively modern replacement for the profound bow of head and body that remains the supreme act of liturgical reverence in the East.[12] Since in many Anglican, Roman Catholic and Western Orthodox Churches the Blessed Sacrament is normally present behind the altar, genuflection is usual when arriving or passing in front of the altar at the communion rail.

Only during the later Middle Ages, centuries after it had become customary to genuflect to persons in authority such as bishops, was genuflection to the Blessed Sacrament introduced. The practice gradually spread and became viewed as obligatory only from the end of the fifteenth century, receiving formal recognition in 1502. The raising of the consecrated Host and Chalice after the Consecration in order to show them to the people was for long unaccompanied by obligatory genuflections.[12]

The requirement that genuflection take place on both knees before the Blessed Sacrament when it is unveiled as at Expositions (but not when it is lying on the corporal during Mass)[12] was altered in 1973 with introduction of the following rule: "Genuflection in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, whether reserved in the tabernacle or exposed for public adoration, is on one knee."[13] "Since a genuflection is, per se, an act of adoration, the general liturgical norms no longer make any distinction between the mode of adoring Christ reserved in the tabernacle or exposed upon the altar. The simple single genuflection on one knee may be used in all cases."[14] However, in some countries the episcopal conference has chosen to retain the double genuflection to the Blessed Sacrament, which is performed by kneeling briefly on both knees and reverently bowing the head with hands joined.[14]

As a result of the custom of genuflecting to the sacrament, it is customary in some countries, Germany for example, for people attending mass to genuflect before entering their pew during mass and when leaving it. Though the sacrament in its tabernacle is the “recipient” of this sign of respect, it is almost invariably performed in the direction of the (high) altar, and the crucifix above or behind it as being the most easily recognisable landmark in any church (it is also almost always in close proximity to the tabernacle).

Episcopalian practice

In the Episcopal Church, genuflection is an act of personal piety and is not required by the prayer book. In some parishes it is a customary gesture of reverence for Christ's real presence in the consecrated Eucharistic elements of bread and wine, particularly in parishes with an Anglo-Catholic tradition.[15]

Generally, if the Blessed Sacrament is reserved in the church, it is customary to acknowledge the Lord's presence with a brief act of worship on entering or leaving the building – normally, a genuflection in the direction of the place of reservation.[16]

During the Liturgy

The General Instruction of the Roman Missal lays down the following rules for genuflections during Mass:[17]

During Mass, three genuflections are made by the priest celebrant: namely, after the showing of the host, after the showing of the chalice, and before Communion. Certain specific features to be observed in a concelebrated Mass are noted in their proper place (cf. nos. 210-251).

If, however, the tabernacle with the Most Blessed Sacrament is present in the sanctuary, the priest, the deacon, and the other ministers genuflect when they approach the altar and when they depart from the sanctuary, but not during the celebration of Mass itself.

Otherwise all who pass before the Most Blessed Sacrament genuflect, unless they are moving in procession.

Ministers carrying the processional cross or candles bow their heads instead of genuflecting.

Other genuflections

In the Byzantine Rite, most widely observed in the Eastern Orthodox Church, genuflection plays a smaller role and prostration, known as proskynesis, is much more common. During the holy mystery of reconciliation, however, following confession of sins, the penitent is to genuflect with head bowed before the Gospel Book or an icon of Christ as the confessor - either a bishop or a presbyter - formally declares God's forgiveness.

Genuflection or kneeling is prescribed at various points of the Roman Rite liturgy, such as after the mention of Jesus' death on the cross in the readings of the Passion during Holy Week.

A right knee genuflection is made during and after the Adoration of the Cross on Good Friday.[8]

A genuflection is made at the mention of the Incarnation in the words et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria Virgine, et homo factus est ("and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man") in the Creed on the solemnities of Christmas and the Annunciation.[18]

It is common practice that during the recital of the Angelus prayer, for the lines "And the Word was made flesh/And dwelt among us", those reciting the prayer bow or genuflect.[19]

Tridentine Mass

In the Tridentine Mass this genuflection is made on any day on which the Creed is recited at Mass, as well as at several other points:

- at the words et Verbum caro factum est ("and the Word became flesh")[20] in the prologue of the Gospel of John, which is the usual Last Gospel, as well as the Gospel for the third Mass on Christmas.

- at the words et procidentes adoraverunt eum ("and falling down they adored him") in the Gospel for the Epiphany, Matthew 2:1-12 (which before 1960 was also the Last Gospel of the third Mass on Christmas)

- at the words Adiuva nos ... during the (identical) Tract said on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays in Lent, except on Ember Wednesday. But no genuflection is envisaged when after Septuagesima the same Tract is used in the votive Mass at a time of Mortality (Missa votiva tempore mortalitatis)

- at the words et procidens adoravit eum ("and falling down he adored him") at the end of the Gospel for Wednesday in the Fourth Week of Lent, John 9:1-38

- at the words ut in nomine Iesu omne genu flectatur caelestium, terrestrium et infernorum ("that in the name of Jesus every knee should bow of those that are in heaven, on earth, and under the earth") in the Epistle (Philippians 2:5–11) of Palm Sunday, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on 14 September (and also, before 1960, the Feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross on 3 May) and in the Epistle (Philippians 2:8–11) of the votive Mass of the Passion of the Lord.

- at the words Veni, sancte Spiritus in the Alleluia before the Sequence on Pentecost Sunday and the Octave of Pentecost and in the votive Mass of the Holy Spirit

In the Maronite Catholic Church, there is an evocative ceremony of genuflection on the feast of Pentecost. The congregation genuflects first on the left knee to God the Father, then on the right knee to God the Son, and finally on both knees to God the Holy Spirit.

Genuflecting to a bishop

From the custom of genuflecting to kings and other nobles arose the custom by which lay people or clergy of lesser rank genuflect to a prelate and kiss his episcopal ring,[21] as a sign of acceptance of the bishop's apostolic authority as representing Christ in the local church,[22] and originally their social position as lords. Abbots and other senior monastics often received genuflection from their monks and often others.

Genuflecting before greater prelates (i.e. Bishops in their own dioceses, Metropolitans in their province, Papal Legates in the territory assigned to them, and Cardinals either outside of Rome or in the church assigned to them in Rome) is treated as obligatory in editions of the Caeremoniale Episcoporum earlier than that of 1985;[23] during liturgical functions according to these prescriptions, clergy genuflect when passing before such prelates, but an officiating priest and any more junior prelates, canons, etc. substitute a bow of the head and shoulders for the genuflection.[12]

The present Catholic liturgical books exclude genuflecting to a bishop during the liturgy: "A genuflection, made by bending the right knee to the ground, signifies adoration, and therefore it is reserved for the Most Blessed Sacrament, as well as for the Holy Cross from the solemn adoration during the liturgical celebration on Good Friday until the beginning of the Easter Vigil."[17] But outside of the liturgy some continue to genuflect or kneel to kiss a bishop's ring.[24]

Though it is frequently asserted that genuflections are to be made on the left knee when made to merely human authorities,[8] there is no such prescription in any liturgical book.

Image gallery

Woodcut depicting marriage proposal - genuflection (kneel/squat combination)

Woodcut depicting marriage proposal - genuflection (kneel/squat combination)

See also

References

- 1 2 Allen, John (1 September 2008). Desmond Tutu. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1556527982. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

Devout "high church" Anglicans genuflect as they pass the reserved sacrament.

- 1 2 Armstrong, John H.; Eagle, Paul E. (26 May 2009). Understanding Four Views on the Lord's Supper. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310542759.

Lutherans worship Christ wherever he is, including the sacraments, and thus Luther genuflected before the baptismal font and the sacrament.

- 1 2 Ingram, Kristen Johnson; Johnson, Kristin J (2004). Beyond Words. Church Publishing, Inc. p. 27. ISBN 0819219738. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Customs - Western Orthodox". Saint Mark's Parish Church. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

To 'genuflect' (kneel down briefly and then arise) is the Western Orthodox way of venerating the sacrament or the altar. To take your place in church, walk quietly down the center aisle, and then genuflect before moving to the left or right into the pew. The same is done when leaving the pew, either to go up to communion or to leave after the service is over. The clergy and faithful also genuflect or bow when passing by the vessel in which the blessed sacrament is reserved. Another time to genuflect is at these words of the creed: 'Who for us men and for our salvation, came down from heaven, And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.'

- ↑ "The Sign of the Cross, bowing and genuflecting, what is it?". Oklahoma, US: Saint Paul's Episcopal Church. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Andrew Chugg, Alexander's Lovers ISBN 978-1-4116-9960-1, p. 103

- ↑ James Allan Stewart Evans, The Age of Justinian ISBN 978-0-415-23726-0, p. 101

- 1 2 3 "Genuflection — which knee is which?", The Compass, March 19, 2011, Catholic Diocese of Green Bay, Wisconsin

- ↑ "Occurrences of the verb "to kneel" in the KJV Bible".

- ↑ "St Mary's Roman Catholic Church". www.stmarysgloucestercity.org. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ "Sacred Congregation for the Sacraments and Divine Worship", Inaestimable donum, §26, 17 April 1980

- 1 2 3 4 Bergh, Frederick Thomas. "Genuflexion". The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 7 October 2016.

- ↑ De Sacra Communione et de Cultu Mysterii Eucharistici extra Missam, 84

- 1 2 "Tabernacles, Adoration and Double Genuflections". www.ewtn.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ "Genuflection, or Genuflexion". 22 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ ""What is Genuflection?", St. Paul's Episcopla Church, Holdenville, Oklahoma". Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- 1 2 "The General Instruction of the Roman Missal" (PDF). Australian Catholic Bishops’ Conference. May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2008.

- ↑ "Why Do Catholics Do That - Holy Spirit Church". www.hsccatl.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ Looney, Edward. "Promoting the Angelus as an Advent Devotion", Catholic Lane, December 01, 2014

- ↑ John 1:1–14

- ↑ Canons of the Holy Orthodox Church, American Jurisdiction Archived February 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Stravinskas, Peter M. J. (3 March 1994). The Catholic Answer Book. Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 9780879737375. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Book 1, chapter XVIII of the 1886 edition" (PDF). Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ Baciamano Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Genuflexion". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Genuflexion". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.