Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter. The others are solid, liquid, and plasma.[1]

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or compound molecules made from a variety of atoms (e.g. carbon dioxide). A gas mixture, such as air, contains a variety of pure gases. What distinguishes gases from liquids and solids is the vast separation of the individual gas particles. This separation usually makes a colorless gas invisible to the human observer.

The gaseous state of matter occurs between the liquid and plasma states,[2] the latter of which provides the upper-temperature boundary for gases. Bounding the lower end of the temperature scale lie degenerative quantum gases[3] which are gaining increasing attention.[4] High-density atomic gases super-cooled to very low temperatures are classified by their statistical behavior as either Bose gases or Fermi gases. For a comprehensive listing of these exotic states of matter, see list of states of matter.

Elemental gases

The only chemical elements that are stable diatomic homonuclear molecular gases at STP are hydrogen (H2), nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and two halogens: fluorine (F2) and chlorine (Cl2). When grouped with the monatomic noble gases – helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), and radon (Rn) – these gases are referred to as "elemental gases".

Etymology

The word gas was first used by the early 17th-century Flemish chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont.[5] He identified carbon dioxide, the first known gas other than air.[6] Van Helmont's word appears to have been simply a phonetic transcription of the Ancient Greek word χάος 'chaos' – the g in Dutch being pronounced like ch in "loch" (voiceless velar fricative, /x/) – in which case Van Helmont simply was following the established alchemical usage first attested in the works of Paracelsus. According to Paracelsus's terminology, chaos meant something like 'ultra-rarefied water'.[7]

An alternative story is that Van Helmont's term was derived from "gahst (or geist), which signifies a ghost or spirit".[8] That story is given no credence by the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary.[9] In contrast, the French-American historian Jacques Barzun speculated that Van Helmont had borrowed the word from the German Gäscht, meaning the froth resulting from fermentation.[10]

Physical characteristics

Because most gases are difficult to observe directly, they are described through the use of four physical properties or macroscopic characteristics: pressure, volume, number of particles (chemists group them by moles) and temperature. These four characteristics were repeatedly observed by scientists such as Robert Boyle, Jacques Charles, John Dalton, Joseph Gay-Lussac and Amedeo Avogadro for a variety of gases in various settings. Their detailed studies ultimately led to a mathematical relationship among these properties expressed by the ideal gas law (see simplified models section below).

Gas particles are widely separated from one another, and consequently, have weaker intermolecular bonds than liquids or solids. These intermolecular forces result from electrostatic interactions between gas particles. Like-charged areas of different gas particles repel, while oppositely charged regions of different gas particles attract one another; gases that contain permanently charged ions are known as plasmas. Gaseous compounds with polar covalent bonds contain permanent charge imbalances and so experience relatively strong intermolecular forces, although the compound's net charge remains neutral. Transient, randomly induced charges exist across non-polar covalent bonds of molecules and electrostatic interactions caused by them are referred to as Van der Waals forces. The interaction of these intermolecular forces varies within a substance which determines many of the physical properties unique to each gas.[11][12] A comparison of boiling points for compounds formed by ionic and covalent bonds leads us to this conclusion.[13]

Compared to the other states of matter, gases have low density and viscosity. Pressure and temperature influence the particles within a certain volume. This variation in particle separation and speed is referred to as compressibility. This particle separation and size influences optical properties of gases as can be found in the following list of refractive indices. Finally, gas particles spread apart or diffuse in order to homogeneously distribute themselves throughout any container.

Macroscopic view of gases

When observing a gas, it is typical to specify a frame of reference or length scale. A larger length scale corresponds to a macroscopic or global point of view of the gas. This region (referred to as a volume) must be sufficient in size to contain a large sampling of gas particles. The resulting statistical analysis of this sample size produces the "average" behavior (i.e. velocity, temperature or pressure) of all the gas particles within the region. In contrast, a smaller length scale corresponds to a microscopic or particle point of view.

Macroscopically, the gas characteristics measured are either in terms of the gas particles themselves (velocity, pressure, or temperature) or their surroundings (volume). For example, Robert Boyle studied pneumatic chemistry for a small portion of his career. One of his experiments related the macroscopic properties of pressure and volume of a gas. His experiment used a J-tube manometer which looks like a test tube in the shape of the letter J. Boyle trapped an inert gas in the closed end of the test tube with a column of mercury, thereby making the number of particles and the temperature constant. He observed that when the pressure was increased in the gas, by adding more mercury to the column, the trapped gas' volume decreased (this is known as an inverse relationship). Furthermore, when Boyle multiplied the pressure and volume of each observation, the product was constant. This relationship held for every gas that Boyle observed leading to the law, (PV=k), named to honor his work in this field.

There are many mathematical tools available for analyzing gas properties. As gases are subjected to extreme conditions, these tools become more complex, from the Euler equations for inviscid flow to the Navier–Stokes equations[14] that fully account for viscous effects. These equations are adapted to the conditions of the gas system in question. Boyle's lab equipment allowed the use of algebra to obtain his analytical results. His results were possible because he was studying gases in relatively low pressure situations where they behaved in an "ideal" manner. These ideal relationships apply to safety calculations for a variety of flight conditions on the materials in use. The high technology equipment in use today was designed to help us safely explore the more exotic operating environments where the gases no longer behave in an "ideal" manner. This advanced math, including statistics and multivariable calculus, makes possible the solution to such complex dynamic situations as space vehicle reentry. An example is the analysis of the space shuttle reentry pictured to ensure the material properties under this loading condition are appropriate. In this flight regime, the gas is no longer behaving ideally.

Pressure

The symbol used to represent pressure in equations is "p" or "P" with SI units of pascals.

When describing a container of gas, the term pressure (or absolute pressure) refers to the average force per unit area that the gas exerts on the surface of the container. Within this volume, it is sometimes easier to visualize the gas particles moving in straight lines until they collide with the container (see diagram at top of the article). The force imparted by a gas particle into the container during this collision is the change in momentum of the particle.[15] During a collision only the normal component of velocity changes. A particle traveling parallel to the wall does not change its momentum. Therefore, the average force on a surface must be the average change in linear momentum from all of these gas particle collisions.

Pressure is the sum of all the normal components of force exerted by the particles impacting the walls of the container divided by the surface area of the wall.

Temperature

The symbol used to represent temperature in equations is T with SI units of kelvins.

The speed of a gas particle is proportional to its absolute temperature. The volume of the balloon in the video shrinks when the trapped gas particles slow down with the addition of extremely cold nitrogen. The temperature of any physical system is related to the motions of the particles (molecules and atoms) which make up the [gas] system.[16] In statistical mechanics, temperature is the measure of the average kinetic energy stored in a molecule (also known as the thermal energy). The methods of storing this energy are dictated by the degrees of freedom of the molecule itself (energy modes). Thermal (kinetic) energy added to a gas or liquid (an endothermic process) produces translational, rotational, and vibrational motion. In contrast, a solid can only increase its internal energy by exciting additional vibrational modes, as the crystal lattice structure prevents both translational and rotational motion. These heated gas molecules have a greater speed range (wider distribution of speeds) with a higher average or mean speed. The variance of this distribution is due to the speeds of individual particles constantly varying, due to repeated collisions with other particles. The speed range can be described by the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. Use of this distribution implies ideal gases near thermodynamic equilibrium for the system of particles being considered.

Specific volume

The symbol used to represent specific volume in equations is "v" with SI units of cubic meters per kilogram.

The symbol used to represent volume in equations is "V" with SI units of cubic meters.

When performing a thermodynamic analysis, it is typical to speak of intensive and extensive properties. Properties which depend on the amount of gas (either by mass or volume) are called extensive properties, while properties that do not depend on the amount of gas are called intensive properties. Specific volume is an example of an intensive property because it is the ratio of volume occupied by a unit of mass of a gas that is identical throughout a system at equilibrium.[17] 1000 atoms a gas occupy the same space as any other 1000 atoms for any given temperature and pressure. This concept is easier to visualize for solids such as iron which are incompressible compared to gases. However, volume itself --- not specific --- is an extensive property.

Density

The symbol used to represent density in equations is ρ (rho) with SI units of kilograms per cubic meter. This term is the reciprocal of specific volume.

Since gas molecules can move freely within a container, their mass is normally characterized by density. Density is the amount of mass per unit volume of a substance, or the inverse of specific volume. For gases, the density can vary over a wide range because the particles are free to move closer together when constrained by pressure or volume. This variation of density is referred to as compressibility. Like pressure and temperature, density is a state variable of a gas and the change in density during any process is governed by the laws of thermodynamics. For a static gas, the density is the same throughout the entire container. Density is therefore a scalar quantity. It can be shown by kinetic theory that the density is inversely proportional to the size of the container in which a fixed mass of gas is confined. In this case of a fixed mass, the density decreases as the volume increases.

Microscopic view of gases

If one could observe a gas under a powerful microscope, one would see a collection of particles without any definite shape or volume that are in more or less random motion. These gas particles only change direction when they collide with another particle or with the sides of the container. This microscopic view of gas is well-described by statistical mechanics, but it can be described by many different theories. The kinetic theory of gases, which makes the assumption that these collisions are perfectly elastic, does not account for intermolecular forces of attraction and repulsion.

Kinetic theory of gases

Kinetic theory provides insight into the macroscopic properties of gases by considering their molecular composition and motion. Starting with the definitions of momentum and kinetic energy,[18] one can use the conservation of momentum and geometric relationships of a cube to relate macroscopic system properties of temperature and pressure to the microscopic property of kinetic energy per molecule. The theory provides averaged values for these two properties.

The kinetic theory of gases can help explain how the system (the collection of gas particles being considered) responds to changes in temperature, with a corresponding change in kinetic energy.

For example: Imagine you have a sealed container of a fixed-size (a constant volume), containing a fixed-number of gas particles; starting from absolute zero (the theoretical temperature at which atoms or molecules have no thermal energy, i.e. are not moving or vibrating), you begin to add energy to the system by heating the container, so that energy transfers to the particles inside. Once their internal energy is above zero-point energy, meaning their kinetic energy (also known as thermal energy) is non-zero, the gas particles will begin to move around the container. As the box is further heated (as more energy is added), the individual particles increase their average speed as the system's total internal energy increases. The higher average-speed of all the particles leads to a greater rate at which collisions happen (i.e. greater number of collisions per unit of time), between particles and the container, as well as between the particles themselves.

The macroscopic, measurable quantity of pressure, is the direct result of these microscopic particle collisions with the surface, over which, individual molecules exert a small force, each contributing to the total force applied within a specific area. (Read "Pressure" in the above section "Macroscopic view of gases".)

Likewise, the macroscopically measurable quantity of temperature, is a quantification of the overall amount of motion, or kinetic energy that the particles exhibit. (Read "Temperature" in the above section "Macroscopic view of gases".)

Thermal motion and statistical mechanics

In the kinetic theory of gases, kinetic energy is assumed to purely consist of linear translations according to a speed distribution of particles in the system. However, in real gases and other real substances, the motions which define the kinetic energy of a system (which collectively determine the temperature), are much more complex than simple linear translation due to the more complex structure of molecules, compared to single atoms which act similarly to point-masses. In real thermodynamic systems, quantum phenomena play a large role in determining thermal motions. The random, thermal motions (kinetic energy) in molecules is a combination of a finite set of possible motions including translation, rotation, and vibration. This finite range of possible motions, along with the finite set of molecules in the system, leads to a finite number of microstates within the system; we call the set of all microstates an ensemble. Specific to atomic or molecular systems, we could potentially have three different kinds of ensemble, depending on the situation: microcanonical ensemble, canonical ensemble, or grand canonical ensemble. Specific combinations of microstates within an ensemble are how we truly define macrostate of the system (temperature, pressure, energy, etc.). In order to do that, we must first count all microstates though use of a partition function. The use of statistical mechanics and the partition function is an important tool throughout all of physical chemistry, because it is the key to connection between the microscopic states of a system and the macroscopic variables which we can measure, such as temperature, pressure, heat capacity, internal energy, enthalpy, and entropy, just to name a few. (Read: Partition function Meaning and significance)

Using the partition function to find the energy of a molecule, or system of molecules, can sometimes be approximated by the Equipartition theorem, which greatly-simplifies calculation. However, this method assumes all molecular degrees of freedom are equally populated, and therefore equally utilized for storing energy within the molecule. It would imply that internal energy changes linearly with temperature, which is not the case. This ignores the fact that heat capacity changes with temperature, due to certain degrees of freedom being unreachable (a.k.a. "frozen out") at lower temperatures. As internal energy of molecules increases, so does the ability to store energy within additional degrees of freedom. As more degrees of freedom become available to hold energy, this causes the molar heat capacity of the substance to increase.[19]

Brownian motion

Brownian motion is the mathematical model used to describe the random movement of particles suspended in a fluid. The gas particle animation, using pink and green particles, illustrates how this behavior results in the spreading out of gases (entropy). These events are also described by particle theory.

Since it is at the limit of (or beyond) current technology to observe individual gas particles (atoms or molecules), only theoretical calculations give suggestions about how they move, but their motion is different from Brownian motion because Brownian motion involves a smooth drag due to the frictional force of many gas molecules, punctuated by violent collisions of an individual (or several) gas molecule(s) with the particle. The particle (generally consisting of millions or billions of atoms) thus moves in a jagged course, yet not so jagged as would be expected if an individual gas molecule were examined.

Intermolecular forces - the primary difference between Real and Ideal gases

Forces between two or more molecules or atoms, either attractive or repulsive, are called intermolecular forces. Intermolecular forces are experienced by molecules when they are within physical proximity of one another. These forces are very important for properly modeling molecular systems, as to accurately predict the microscopic behavior of molecules in any system, and therefore, are necessary for accurately predicting the physical properties of gases (and liquids) across wide variations in physical conditions.

Arising from the study of physical chemistry, one of the most prominent intermolecular forces throughout physics, are van der Waals forces. Van der Waals forces play a key role in determining nearly all physical properties of fluids such as viscosity, flow rate, and gas dynamics (see physical characteristics section). The van der Waals interactions between gas molecules, is the reason why modeling a "real gas" is more mathematically difficult than an "ideal gas". Ignoring these proximity-dependent forces allows a real gas to be treated like an ideal gas, which greatly simplifies calculation.

The intermolecular attractions and repulsions between two gas molecules are dependent on the amount of distance between them. The combined attractions and repulsions are well-modelled by the Lennard-Jones potential, which is one of the most extensively studied of all interatomic potentials describing the potential energy of molecular systems. The Lennard-Jones potential between molecules can be broken down into two separate components: a long-distance attraction due to the London dispersion force, and a short-range repulsion due to electron-electron exchange interaction (which is related to the Pauli exclusion principle).

When two molecules are relatively distant (meaning they have a high potential energy), they experience a weak attracting force, causing them to move toward each other, lowering their potential energy. However, if the molecules are too far away, then they would not experience attractive force of any significance. Additionally, if the molecules get too close then they will collide, and experience a very high repulsive force (modelled by Hard spheres) which is a much stronger force than the attractions, so that any attraction due to proximity is disregarded.

As two molecules approach each other, from a distance that is neither too-far, nor too-close, their attraction increases as the magnitude of their potential energy increases (becoming more negative), and lowers their total internal energy.[20] The attraction causing the molecules to get closer, can only happen if the molecules remain in proximity for the duration of time it takes to physically move closer. Therefore, the attractive forces are strongest when the molecules move at low speeds. This means that the attraction between molecules is significant when gas temperatures is low. However, if you were to isothermally compress this cold gas into a small volume, forcing the molecules into close proximity, and raising the pressure, the repulsions will begin to dominate over the attractions, as the rate at which collisions are happening will increase significantly. Therefore, at low temperatures, and low pressures, attraction is the dominant intermolecular interaction.

If two molecules are moving at high speeds, in arbitrary directions, along non-intersecting paths, then they will not spend enough time in proximity to be affected by the attractive London-dispersion force. If the two molecules collide, they are moving too fast and their kinetic energy will be much greater than any attractive potential energy, so they will only experience repulsion upon colliding. Thus, attractions between molecules can be neglected at high temperatures due to high speeds. At high temperatures, and high pressures, repulsion is the dominant intermolecular interaction.

Accounting for the above stated effects which cause these attractions and repulsions, real gases, delineate from the ideal gas model by the following generalization:[21]

- At low temperatures, and low pressures, the volume occupied by a real gas, is less than the volume predicted by the ideal gas law.

- At high temperatures, and high pressures, the volume occupied by a real gas, is greater than the volume predicted by the ideal gas law.

Mathematical models

An equation of state (for gases) is a mathematical model used to roughly describe or predict the state properties of a gas. At present, there is no single equation of state that accurately predicts the properties of all gases under all conditions. Therefore, a number of much more accurate equations of state have been developed for gases in specific temperature and pressure ranges. The "gas models" that are most widely discussed are "perfect gas", "ideal gas" and "real gas". Each of these models has its own set of assumptions to facilitate the analysis of a given thermodynamic system.[22] Each successive model expands the temperature range of coverage to which it applies.

Ideal and perfect gas

The equation of state for an ideal or perfect gas is the ideal gas law and reads

where P is the pressure, V is the volume, n is amount of gas (in mol units), R is the universal gas constant, 8.314 J/(mol K), and T is the temperature. Written this way, it is sometimes called the "chemist's version", since it emphasizes the number of molecules n. It can also be written as

where is the specific gas constant for a particular gas, in units J/(kg K), and ρ = m/V is density. This notation is the "gas dynamicist's" version, which is more practical in modeling of gas flows involving acceleration without chemical reactions.

The ideal gas law does not make an assumption about the specific heat of a gas. In the most general case, the specific heat is a function of both temperature and pressure. If the pressure-dependence is neglected (and possibly the temperature-dependence as well) in a particular application, sometimes the gas is said to be a perfect gas, although the exact assumptions may vary depending on the author and/or field of science.

For an ideal gas, the ideal gas law applies without restrictions on the specific heat. An ideal gas is a simplified "real gas" with the assumption that the compressibility factor Z is set to 1 meaning that this pneumatic ratio remains constant. A compressibility factor of one also requires the four state variables to follow the ideal gas law.

This approximation is more suitable for applications in engineering although simpler models can be used to produce a "ball-park" range as to where the real solution should lie. An example where the "ideal gas approximation" would be suitable would be inside a combustion chamber of a jet engine.[23] It may also be useful to keep the elementary reactions and chemical dissociations for calculating emissions.

Real gas

Each one of the assumptions listed below adds to the complexity of the problem's solution. As the density of a gas increases with rising pressure, the intermolecular forces play a more substantial role in gas behavior which results in the ideal gas law no longer providing "reasonable" results. At the upper end of the engine temperature ranges (e.g. combustor sections – 1300 K), the complex fuel particles absorb internal energy by means of rotations and vibrations that cause their specific heats to vary from those of diatomic molecules and noble gases. At more than double that temperature, electronic excitation and dissociation of the gas particles begins to occur causing the pressure to adjust to a greater number of particles (transition from gas to plasma).[24] Finally, all of the thermodynamic processes were presumed to describe uniform gases whose velocities varied according to a fixed distribution. Using a non-equilibrium situation implies the flow field must be characterized in some manner to enable a solution. One of the first attempts to expand the boundaries of the ideal gas law was to include coverage for different thermodynamic processes by adjusting the equation to read pVn = constant and then varying the n through different values such as the specific heat ratio, γ.

Real gas effects include those adjustments made to account for a greater range of gas behavior:

- Compressibility effects (Z allowed to vary from 1.0)

- Variable heat capacity (specific heats vary with temperature)

- Van der Waals forces (related to compressibility, can substitute other equations of state)

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamic effects

- Issues with molecular dissociation and elementary reactions with variable composition.

For most applications, such a detailed analysis is excessive. Examples where real gas effects would have a significant impact would be on the Space Shuttle re-entry where extremely high temperatures and pressures were present or the gases produced during geological events as in the image of the 1990 eruption of Mount Redoubt.

Permanent gas

Permanent gas is a term used for a gas which has a critical temperature below the range of normal human-habitable temperatures and therefore cannot be liquefied by pressure within this range. Historically such gases were thought to be impossible to liquefy and would therefore permanently remain in the gaseous state. The term is relevant to ambient temperature storage and transport of gases at high pressure.[25]

Historical research

Boyle's law

Boyle's law was perhaps the first expression of an equation of state. In 1662 Robert Boyle performed a series of experiments employing a J-shaped glass tube, which was sealed on one end. Mercury was added to the tube, trapping a fixed quantity of air in the short, sealed end of the tube. Then the volume of gas was carefully measured as additional mercury was added to the tube. The pressure of the gas could be determined by the difference between the mercury level in the short end of the tube and that in the long, open end. The image of Boyle's equipment shows some of the exotic tools used by Boyle during his study of gases.

Through these experiments, Boyle noted that the pressure exerted by a gas held at a constant temperature varies inversely with the volume of the gas.[26] For example, if the volume is halved, the pressure is doubled; and if the volume is doubled, the pressure is halved. Given the inverse relationship between pressure and volume, the product of pressure (P) and volume (V) is a constant (k) for a given mass of confined gas as long as the temperature is constant. Stated as a formula, thus is:

Because the before and after volumes and pressures of the fixed amount of gas, where the before and after temperatures are the same both equal the constant k, they can be related by the equation:

Charles's law

In 1787, the French physicist and balloon pioneer, Jacques Charles, found that oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and air expand to the same extent over the same 80 kelvin interval. He noted that, for an ideal gas at constant pressure, the volume is directly proportional to its temperature:

Gay-Lussac's law

In 1802, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac published results of similar, though more extensive experiments.[27] Gay-Lussac credited Charles' earlier work by naming the law in his honor. Gay-Lussac himself is credited with the law describing pressure, which he found in 1809. It states that the pressure exerted on a container's sides by an ideal gas is proportional to its temperature.

Avogadro's law

In 1811, Amedeo Avogadro verified that equal volumes of pure gases contain the same number of particles. His theory was not generally accepted until 1858 when another Italian chemist Stanislao Cannizzaro was able to explain non-ideal exceptions. For his work with gases a century prior, the physical constant that bears his name (the Avogadro constant) is the number of atoms per mole of elemental carbon-12 (6.022×1023 mol−1). This specific number of gas particles, at standard temperature and pressure (ideal gas law) occupies 22.40 liters, which is referred to as the molar volume.

Avogadro's law states that the volume occupied by an ideal gas is proportional to the amount of substance in the volume. This gives rise to the molar volume of a gas, which at STP is 22.4 dm3/mol (liters per mole). The relation is given by

where n is the amount of substance of gas (the number of molecules divided by the Avogadro constant).

Dalton's law

In 1801, John Dalton published the law of partial pressures from his work with ideal gas law relationship: The pressure of a mixture of non reactive gases is equal to the sum of the pressures of all of the constituent gases alone. Mathematically, this can be represented for n species as:

- Pressuretotal = Pressure1 + Pressure2 + ... + Pressuren

The image of Dalton's journal depicts symbology he used as shorthand to record the path he followed. Among his key journal observations upon mixing unreactive "elastic fluids" (gases) were the following:[28]

- Unlike liquids, heavier gases did not drift to the bottom upon mixing.

- Gas particle identity played no role in determining final pressure (they behaved as if their size was negligible).

Special topics

Compressibility

Thermodynamicists use this factor (Z) to alter the ideal gas equation to account for compressibility effects of real gases. This factor represents the ratio of actual to ideal specific volumes. It is sometimes referred to as a "fudge-factor" or correction to expand the useful range of the ideal gas law for design purposes. Usually this Z value is very close to unity. The compressibility factor image illustrates how Z varies over a range of very cold temperatures.

Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number is the ratio of inertial forces (vsρ) to viscous forces (μ/L). It is one of the most important dimensionless numbers in fluid dynamics and is used, usually along with other dimensionless numbers, to provide a criterion for determining dynamic similitude. As such, the Reynolds number provides the link between modeling results (design) and the full-scale actual conditions. It can also be used to characterize the flow.

Viscosity

Viscosity, a physical property, is a measure of how well adjacent molecules stick to one another. A solid can withstand a shearing force due to the strength of these sticky intermolecular forces. A fluid will continuously deform when subjected to a similar load. While a gas has a lower value of viscosity than a liquid, it is still an observable property. If gases had no viscosity, then they would not stick to the surface of a wing and form a boundary layer. A study of the delta wing in the Schlieren image reveals that the gas particles stick to one another (see Boundary layer section).

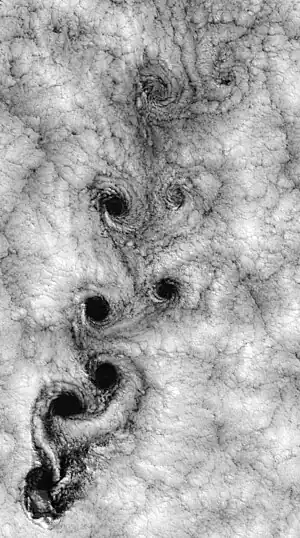

Turbulence

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is a flow regime characterized by chaotic, stochastic property changes. This includes low momentum diffusion, high momentum convection, and rapid variation of pressure and velocity in space and time. The satellite view of weather around Robinson Crusoe Islands illustrates one example.

Boundary layer

Particles will, in effect, "stick" to the surface of an object moving through it. This layer of particles is called the boundary layer. At the surface of the object, it is essentially static due to the friction of the surface. The object, with its boundary layer is effectively the new shape of the object that the rest of the molecules "see" as the object approaches. This boundary layer can separate from the surface, essentially creating a new surface and completely changing the flow path. The classical example of this is a stalling airfoil. The delta wing image clearly shows the boundary layer thickening as the gas flows from right to left along the leading edge.

Maximum entropy principle

As the total number of degrees of freedom approaches infinity, the system will be found in the macrostate that corresponds to the highest multiplicity. In order to illustrate this principle, observe the skin temperature of a frozen metal bar. Using a thermal image of the skin temperature, note the temperature distribution on the surface. This initial observation of temperature represents a "microstate". At some future time, a second observation of the skin temperature produces a second microstate. By continuing this observation process, it is possible to produce a series of microstates that illustrate the thermal history of the bar's surface. Characterization of this historical series of microstates is possible by choosing the macrostate that successfully classifies them all into a single grouping.

Thermodynamic equilibrium

When energy transfer ceases from a system, this condition is referred to as thermodynamic equilibrium. Usually, this condition implies the system and surroundings are at the same temperature so that heat no longer transfers between them. It also implies that external forces are balanced (volume does not change), and all chemical reactions within the system are complete. The timeline varies for these events depending on the system in question. A container of ice allowed to melt at room temperature takes hours, while in semiconductors the heat transfer that occurs in the device transition from an on to off state could be on the order of a few nanoseconds.

To From |

Solid | Liquid | Gas | Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Melting | Sublimation | ||

| Liquid | Freezing | Vaporization | ||

| Gas | Deposition | Condensation | Ionization | |

| Plasma | Recombination |

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Gas". Merriam-Webster. 7 August 2023.

- ↑ This early 20th century discussion infers what is regarded as the plasma state. See page 137 of American Chemical Society, Faraday Society, Chemical Society (Great Britain) The Journal of Physical Chemistry, Volume 11 Cornell (1907).

- ↑ Zelevinsky, Tanya (2009-11-09). "—just right for forming a Bose-Einstein condensate". Physics. 2 (20): 94. arXiv:0910.0634. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.200401. PMID 20365964. S2CID 14321276.

- ↑ "Quantum Gas Microscope Offers Glimpse Of Quirky Ultracold Atoms". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- ↑ Helmont, Jan Baptist Van (1652). Ortus medicine, id est initial physicae inaudita... authore Joanne Baptista Van Helmont,... (in Latin). apud L. Elzevirium. The word "gas" first appears on page 58, where he mentions: "... Gas (meum scil. inventum) ..." (... gas (namely, my discovery) ...). On page 59, he states: "... in nominis egestate, halitum illum, Gas vocavi, non longe a Chao ..." (... in need of a name, I called this vapor "gas", not far from "chaos" ...)

- ↑ Ley, Willy (June 1966). "The Re-Designed Solar System". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "gas". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Draper, John William (1861). A textbook on chemistry. New York: Harper and Sons. p. 178.

- ↑ ""gas, n.1 and adj."". OED Online. Oxford University Press. June 2021.

There is probably no foundation in the idea (found from the 18th cent. onwards, e.g. in J. Priestley On Air (1774) Introd. 3) that van Helmont modelled gas on Dutch geest spirit, or any of its cognates

- ↑ Barzun, Jacques (2000). For Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 199.

- ↑ The authors make the connection between molecular forces of metals and their corresponding physical properties. By extension, this concept would apply to gases as well, though not universally. Cornell (1907) pp. 164–5.

- ↑ One noticeable exception to this physical property connection is conductivity which varies depending on the state of matter (ionic compounds in water) as described by Michael Faraday in 1833 when he noted that ice does not conduct a current. See page 45 of John Tyndall's Faraday as a Discoverer (1868).

- ↑ John S. Hutchinson (2008). Concept Development Studies in Chemistry. p. 67.

- ↑ Anderson, p.501

- ↑ J. Clerk Maxwell (1904). Theory of Heat. Mineola: Dover Publications. pp. 319–20. ISBN 978-0-486-41735-6.

- ↑ See pages 137–8 of Society, Cornell (1907).

- ↑ Kenneth Wark (1977). Thermodynamics (3 ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-07-068280-1.

- ↑ For assumptions of kinetic theory see McPherson, pp.60–61

- ↑ Jeschke, Gunnar (26 November 2020). "Canonical Ensemble". Archived from the original on 2021-05-20.

- ↑ "Lennard-Jones Potential - Chemistry LibreTexts". 2020-08-22. Archived from the original on 2020-08-22. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ↑ "14.11: Real and Ideal Gases - Chemistry LibreTexts". 2021-02-06. Archived from the original on 2021-02-06. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ↑ Anderson, pp. 289–291

- ↑ John, p.205

- ↑ John, pp. 247–56

- ↑ "Permanent gas". www.oxfordreference.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ McPherson, pp.52–55

- ↑ McPherson, pp.55–60

- ↑ John P. Millington (1906). John Dalton. pp. 72, 77–78.

References

- Anderson, John D. (1984). Fundamentals of Aerodynamics. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-001656-9.

- John, James (1984). Gas Dynamics. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-08014-4.

- McPherson, William; Henderson, William (1917). An Elementary study of chemistry.

Further reading

- Philip Hill and Carl Peterson. Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Propulsion: Second Edition Addison-Wesley, 1992. ISBN 0-201-14659-2

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Animated Gas Lab. Accessed February 2008.

- Georgia State University. HyperPhysics. Accessed February 2008.

- Antony Lewis WordWeb. Accessed February 2008.

- Northwestern Michigan College The Gaseous State. Accessed February 2008.

- Lewes, Vivian Byam; Lunge, Georg (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). p. 481–493.