Gaius Cassius Longinus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 86 BC[2] |

| Died | 3 October 42 BC (aged 44) |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Resting place | Thasos, Greece |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Other names | Last of the Romans[3] |

| Occupation(s) | General and politician |

| Known for | Assassination of Julius Caesar |

| Office | Tribune of the plebs (49 BC) Praetor (44 BC) Consul designate (41 BC) |

| Spouse | Junia Tertia |

| Children | 1 (Gaius Cassius Longinus) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Roman Republic Pompey |

| Years | 54–42 BC |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Carrhae Caesar's civil war Battle of Philippi |

Gaius Cassius Longinus (Classical Latin: [ˈɡaːi.ʊs ˈkassi.ʊs ˈlɔŋɡɪnʊs]; c. 86 BC – 3 October 42 BC) was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC.[4][5][6] He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the conspiracy. He commanded troops with Brutus during the Battle of Philippi against the combined forces of Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar's former supporters, and committed suicide after being defeated by Mark Antony.

Cassius was elected as Tribune of the plebs in 49 BC. He opposed Caesar, and eventually he commanded a fleet against him during Caesar's Civil War: after Caesar defeated Pompey in the Battle of Pharsalus, Caesar overtook Cassius and forced him to surrender. After Caesar's death, Cassius fled to the East, where he amassed an army of twelve legions. He was supported and made Governor by the Senate. Later he and Brutus marched west against the allies of the Second Triumvirate.

He followed the teachings of the philosopher Epicurus, although scholars debate whether or not these beliefs affected his political life. Cassius is a main character in William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar that depicts the assassination of Caesar and its aftermath. He is also shown in the lowest circle of Hell in Dante's Inferno as punishment for betraying and killing Caesar.[7][8]

Biography

Early life

Gaius Cassius Longinus came from a very old Roman family, gens Cassia, which had been prominent in Rome since the 6th century BC. Little is known of his early life, apart from a story that he showed his dislike of despots while still at school, by quarreling with the son of the dictator Sulla.[9] He studied philosophy at Rhodes under Archelaus of Rhodes and became fluent in Greek.[10] He was married to Junia Tertia, who was the daughter of Servilia and thus a half-sister of his co-conspirator Brutus. They had one son, who was born in about 60 BC.[11]

Carrhae and Syria

In 54 BC, Cassius joined Marcus Licinius Crassus in his eastern campaign against the Parthian Empire. In 53 BC, Crassus suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in Northern-Mesopotamia losing two-thirds of his army. Cassius led the remaining troops' retreat back into Syria, and organised an effective defence force for the province. Based on Plutarch's account, the defeat at Carrhae could have been avoided had Crassus acted as Cassius had advised. According to Dio, the Roman soldiers, as well as Crassus himself, were willing to give the overall command to Cassius after the initial disaster in the battle, which Cassius "very properly" refused. The Parthians also considered Cassius as equal to Crassus in authority, and superior to him in skill.[12]

In 51 BC, Cassius was able to ambush and defeat an invading Parthian army under the command of prince Pacorus and general Osaces. He first refused to do battle with the Parthians, keeping his army behind the walls of Antioch (Syria's most important city) where he was besieged. When the Parthians gave up the siege and started to ravage the countryside, he followed them with his army harrying them as they went. The decisive encounter came on October 7 as the Parthians turned away from Antigonea. As they set about their return journey they were confronted by a detachment of Cassius' army, which faked a retreat and lured the Parthians into an ambush. The Parthians were suddenly surrounded by Cassius' main forces and defeated. Their general Osaces died from his wounds, and the rest of the Parthian army retreated back across the Euphrates.[13]

Civil war

Cassius returned to Rome in 50 BC, when civil war was about to break out between Julius Caesar and Pompey. Cassius was elected tribune of the Plebs for 49 BC, and threw in his lot with the Optimates, although his brother Lucius Cassius supported Caesar. Cassius left Italy shortly after Caesar crossed the Rubicon. He met Pompey in Greece, and was appointed to command part of his fleet.

In 48 BC, Cassius sailed his ships to Sicily, where he attacked and burned a large part of Caesar's navy.[14] He then proceeded to harass ships off the Italian coast. News of Pompey's defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus caused Cassius to head for the Hellespont, with hopes of allying with the king of Pontus, Pharnaces II. Cassius was overtaken by Caesar en route, and was forced to surrender unconditionally.[15]

Caesar made Cassius a legate, employing him in the Alexandrian War against the very same Pharnaces whom Cassius had hoped to join after Pompey's defeat at Pharsalus. However, Cassius refused to join in the fight against Cato and Scipio in Africa, choosing instead to retire to Rome.

Cassius spent the next two years in office, and apparently tightened his friendship with Cicero.[16] In 44 BC, he became praetor peregrinus with the promise of the Syrian province for the ensuing year. The appointment of his junior and brother-in-law, Marcus Brutus, as praetor urbanus deeply offended him.[17]

Although Cassius was "the moving spirit" in the plot against Caesar, winning over the chief assassins to the cause of tyrannicide, Brutus became their leader.[18] On the Ides of March, 44 BC, Cassius urged on his fellow liberators and struck Caesar in the chest. Though they succeeded in assassinating Caesar, the celebration was short-lived, as Mark Antony seized power and turned the public against them. In letters written during 44 BC, Cicero frequently complains that Rome was still subjected to tyranny, because the "Liberators" had failed to kill Antony.[19] According to some accounts, Cassius had wanted to kill Antony at the same time as Caesar, but Brutus dissuaded him.[20]

Post-assassination

Cassius' reputation in the East made it easy to amass an army from other governors in the area, and by 43 BC, he was ready to take on Publius Cornelius Dolabella with 12 legions. By this point, the Senate had split with Antonius, and cast its lot with Cassius, confirming him as governor of the province. Dolabella attacked but was betrayed by his allies, leading him to commit suicide. Cassius was now secure enough to march on Egypt, but on the formation of the Second Triumvirate, Brutus requested his assistance. Cassius quickly joined Brutus in Smyrna with most of his army, leaving his nephew behind to govern Syria as well.

The conspirators decided to attack the triumvirate's allies in Asia. Cassius set upon and sacked Rhodes, while Brutus did the same to Lycia. They regrouped the following year in Sardis, where their armies proclaimed them imperator. They crossed the Hellespont, marched through Thrace, and encamped near Philippi in Macedon. Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian (later known as Augustus) and Mark Antony soon arrived, and Cassius planned to starve them out through the use of their superior position in the country. However, they were forced into a pair of battles by Antony, collectively known as the Battle of Philippi. Brutus was successful against Octavian, and took his camp. Cassius, however, was defeated and overrun by Mark Antony and, unaware of Brutus' victory, ordered his freeman Pindarus to help him kill himself. Pindarus fled afterwards and Cassius' head was found severed from his body. [21] He was mourned by Brutus as "the Last of the Romans" and buried in Thassos.[3]

Epicureanism

"Among that select band of philosophers who have managed to change the world," writes David Sedley, "it would be hard to find a pair with a higher public profile than Brutus and Cassius – brothers-in-law, fellow-assassins, and Shakespearian heroes," adding that "it may not even be widely known that they were philosophers."[22]

Like Brutus, whose Stoic proclivities are widely assumed but who is more accurately described as an Antiochean Platonist, Cassius exercised a long and serious interest in philosophy. His early philosophical commitments are hazy, though D.R. Shackleton Bailey thought that a remark by Cicero[23] indicates a youthful adherence to the Academy.[24] Sometime between 48 and 45 BC, however, Cassius famously converted to the school of thought founded by Epicurus. Although Epicurus advocated a withdrawal from politics, at Rome his philosophy was made to accommodate the careers of many prominent men in public life, among them Caesar's father-in-law, Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus.[25] Arnaldo Momigliano called Cassius' conversion a "conspicuous date in the history of Roman Epicureanism," a choice made not to enjoy the pleasures of the Garden, but to provide a philosophical justification for assassinating a tyrant.[26]

Cicero associates Cassius's new Epicureanism with a willingness to seek peace in the aftermath of the civil war between Caesar and Pompeius.[27] Miriam Griffin dates his conversion to as early as 48 BC, after he had fought on the side of Pompeius at the Battle of Pharsalus but decided to come home instead of joining the last holdouts of the civil war in Africa.[28] Momigliano placed it in 46 BC, based on a letter by Cicero to Cassius dated January 45.[29] Shackleton Bailey points to a date of two or three years earlier.[30]

The dating bears on, but is not essential to, the question of whether Cassius justified the murder of Caesar on Epicurean grounds. Griffin argues that his intellectual pursuits, like those of other Romans, may be entirely removed from any practical application in the realm of politics.[31] Romans of the Late Republic who can be identified as Epicureans are more often found among the supporters of Caesar, and often literally in his camp. Momigliano argued, however, that many of those who opposed Caesar's dictatorship bore no personal animus toward him, and Republicanism was more congenial to the Epicurean way of life than dictatorship. The Roman concept of libertas had been integrated into Greek philosophical studies, and though Epicurus' theory of the political governance admitted various forms of government based on consent, including but not limited to democracy, a tyrannical state was regarded by Roman Epicureans as incompatible with the highest good of pleasure, defined as freedom from pain. Tyranny also threatened the Epicurean value of parrhesia (παρρησία), "truthful speaking," and the movement toward deifying Caesar offended Epicurean belief in abstract gods who lead an ideal existence removed from mortal affairs.[32]

Momigliano saw Cassius as moving from an initial Epicurean orthodoxy, which emphasised disinterest in matters not of vice and virtue, and detachment, to a "heroic Epicureanism."[33] For Cassius, virtue was active. In a letter to Cicero, he wrote:

I hope that people will understand that for all, cruelty exists in proportion to hatred, and goodness and clemency in proportion to love, and evil men most seek out and crave the things which accrue to good men. It's hard to persuade people that ‘the good is desirable for its own sake'; but it's both true and creditable that pleasure and tranquility are obtained by virtue, justice, and the good. Epicurus himself, from whom all your Catii and Amafinii[34] take their leave as poor interpreters of his words, says ‘there is no living pleasantly without living a good and just life.'[35]

Sedley agrees that the conversion of Cassius should be dated to 48, when Cassius stopped resisting Caesar, and finds it unlikely that Epicureanism was a sufficient or primary motivation for his later decision to take violent action against the dictator. Rather, Cassius would have had to reconcile his intention with his philosophical views. Cicero provides evidence[36] that Epicureans recognized circumstances when direct action was justified in a political crisis. In the quotation above, Cassius explicitly rejects the idea that morality is good to be chosen for its own sake; morality, as a means of achieving pleasure and ataraxia, is not inherently superior to the removal of political anxieties.[37]

The inconsistencies between traditional Epicureanism and an active approach to securing freedom ultimately could not be resolved, and during the Empire, the philosophy of political opposition tended to be Stoic. This circumstance, Momigliano argues, helps explain why historians of the Imperial era found Cassius more difficult to understand than Brutus, and less admirable.[33]

Cultural depictions

In Dante's Inferno (Canto XXXIV), Cassius is one of three people deemed sinful enough to be chewed in one of the three mouths of Satan, in the very centre of Hell, for all eternity, as a punishment for killing Julius Caesar. The other two are Brutus, his fellow conspirator, and Judas Iscariot, the Biblical betrayer of Jesus. It is unknown why the third ringleader of the conspiracy to kill Caesar, Decimus Brutus, was not also shown this deep in Hell.

Cassius also plays a major role in Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar (I. ii. 190–195) as the leader of the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar. Caesar distrusts him, and states, "Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look; He thinks too much: such men are dangerous." In one of the final scenes of the play, Cassius mentions to one of his subordinates that the day, October 3, is his birthday, and dies shortly afterwards.

See also

Notes

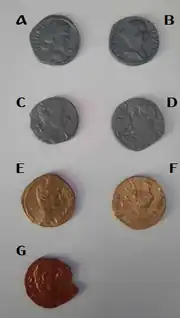

- ↑ Nodelman, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Polo, Francisco Pina; Fernndez, Alejandro Daz (2019). The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic. De Gruyter. p. 232. ISBN 978-3-11-066341-9.

- 1 2 Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 44.2.

- ↑ Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1939, reprinted 2002), p. 57 online; Elizabeth Rawson, "Caesar: Civil War and Dictatorship," in The Cambridge Ancient History: The Last Age of the Roman Republic 146–43 BC (Cambridge University Press, 1994), vol. 9, p. 465.

- ↑ Plutarch. "Life of Caesar". University of Chicago. p. 595.

...at this juncture Decimus Brutus, surnamed Albinus, who was so trusted by Caesar that he was entered in his will as his second heir, but was partner in the conspiracy of the other Brutus and Cassius, fearing that if Caesar should elude that day, their undertaking would become known, ridiculed the seers and chided Caesar for laying himself open to malicious charges on the part of the senators...

- ↑ Suetonius (121). "De Vita Caesarum" [The Twelve Casesars]. University of Chicago. p. 107. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30.

More than sixty joined the conspiracy against [Caesar], led by Gaius Cassius and Marcus and Decimus Brutus.

- ↑ Dante, Inferno: Canto XXXIV

- ↑ Cook, W. R., & Herzman, R. B. (1979). "Inferno XXXIII: The Past and the Present in Dante's "Imagery of Betrayal". Italica, 56(4), 377–383. JSTOR 478665. "For the vision of Satan that is Dante the pilgrim's last glimpse of hell shows the three mouths of Satan gnawing on each of the three great traitors - Brutus, Cassius, and Judas."

- ↑ Plutarch, Brutus, 9.1-4

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars, 4.67.

- ↑ Plutarch, Brutus, 14.4

- ↑ Morrell, Kit (2017). Pompey, Cato, and the Governance of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780198755142.

- ↑ Gareth C. Sampson, The defeat of Rome, Crassus' Carrhae & the invasion of the East, p.159

- ↑ Caesar, Civil War, iii.101.

- ↑ However, both Suetonius (Caesar, 63 Archived 2012-05-30 at archive.today) and Cassius Dio (Roman History, 42.6) say that it was Lucius Cassius who surrendered to Caesar at the Hellespont.

- ↑ In a letter written in 45 BC, Cassius says to Cicero, "There is nothing that gives me more pleasure to do than to write to you; for I seem to be talking and joking with you face to face" (Ad Fam., xv.19).

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (American Philological Association, 1952), vol. 2, p. 320, citing Plutarch, Brutus 7.1–3 and Caesar 62.2; and Appian, Bellum Civile 4.57.

- ↑ For instance, Cicero, Ad Fam., xii.3.1.

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, 2.58.5; Plutarch, Brutus, 18.2-6.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 43.5-6.

- ↑ David Sedley, "The Ethics of Brutus and Cassius," Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997) 41–53.

- ↑ Cicero, Ad familiares xv.16.3.

- ↑ As cited by Miriam Griffin, "Philosophy, Politics, and Politicians at Rome," in Philosophia togata: Essays on Philosophy and Roman Society (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989).

- ↑ For a survey of Roman Epicureans active in politics, see Arnaldo Momigliano, review of Science and Politics in the Ancient World by Benjamin Farrington (London 1939), in Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941), pp. 151–157.

- ↑ Momigliano, Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941), p. 151.

- ↑ Miriam Griffin, "The Intellectual Developments of the Ciceronian Age," in The Cambridge Ancient History (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 726 online.

- ↑ Spe pacis et odio civilis sanguinis ("with a hope of peace and a hatred of shedding blood in civil war"), Cicero, Ad fam. xv.15.1; Miriam Griffin, "Philosophy, Politics, and Politicians at Rome," in Philosophia togata (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989).

- ↑ For a quotation of the Epicurean passage in this letter, see article on the philosopher Catius.

- ↑ D.R. Shackleton Bailey, Cicero Epistulae ad familiares, vol. 2 (Cambridge University Press, 1977), p. 378 online, in a note to one of Cicero's letters to Cassius (Ad fam. xv.17.4), pointing to evidence he believed Momigliano had overlooked.

- ↑ Miriam Griffin, "Philosophy, Politics, and Politicians at Rome," in Philosophia togata (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), particularly citing Plutarch, Caesar 66.2 on a lack of philosophical justification for killing Caesar: Cassius is said to commit the act despite his devotion to Epicurus.

- ↑ Arnaldo Momigliano, Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941), pp. 151–157. Summary of Cassius's Epicureanism also in David Sedley, "The Ethics of Brutus and Cassius," Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997), p. 41.

- 1 2 Momigliano, Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941), p. 157.

- ↑ Catius and Amafinius were Epicurean philosophers known for their popularizing approach and criticized by Cicero for their dumbed-down prose style.

- ↑ Ad familiares xv.19; Shackleton Bailey's Latin text of this letter is available online.

- ↑ Cicero, De republica 1.10.

- ↑ David Sedley, "The Ethics of Brutus and Cassius," Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997), pp. 41 and 46–47.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cassius s.v. 3. Gaius Cassius Longinus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 461.

- Nodelman, Sheldon (1987). "The Portrait of Brutus the Tyrannicide". In Jiří Frel; Arthur Houghton & Marion True (eds.). Ancient Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum: Volume 1. Occasional Papers on Antiquities. Vol. 4. Malibu, CA, US: J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 41–86. ISBN 0-89236-071-2.

Further reading

- Cassius Dio Cocceianus (1987). The Roman History: The Reign of Augustus. Ian Scott-Kilvert, trans. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444483.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1986). Selected Letters. D. R. H. Shackleton Bailey, trans. London: Penguin Books.

- Gowing, Alain M. (1990). "Appian and Cassius' Speech Before Philippi ('Bella Civilia' 4.90–100)". Phoenix. 44 (2): 158–181. doi:10.2307/1088329. JSTOR 1088329.

- Plutarch (1972). Fall of the Roman Republic: Six Lives. Rex Warner, trans. New York: Penguin Books.

- Plutarch (1965). Maker's of Rome: Nine Lives by Plutarch. Ian Scott-Kilvert, trans. London: Penguin Books.

External links

- "Cassius Longinus" in the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Letters to and from Cassius from Cicero's Letters to Friends

- "Life of Brutus"—from Plutarch's Parallel Lives