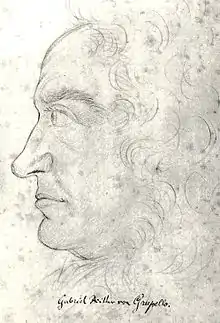

Gabriël Grupello | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, c. 1700 | |

| Born | 22 May 1644 |

| Died | 20 June 1730 (aged 86) |

| Occupation | sculptor |

Gabriël Grupello (also Gabriël de Grupello or Gabriël Reppeli; 22 May 1644 – 20 June 1730) was a Flemish Baroque sculptor who produced religious and mythological sculptures, portraits and public sculptures. He worked in Flanders, France and Germany. He was a virtuoso sculptor who enjoyed the patronage of several European rulers.

Life

Early life and training

Grupello was born as the son of Bernardo Rupelli, an Italian cavalry captain in Spanish service, and his Flemish wife Cornelia Delinck.[1] His father, who died at a young age, was a member of the higher non-aristocratic class of society. Grupello later styled himself as Chevalier de Grupello, but a noble ancestry has not been demonstrated.

At age 14, he started a five-year training as a sculptor in the Antwerp workshop of leading Baroque sculptor Artus Quellinus the Elder.[2] After studying in Italy where he had worked in the workshop of his compatriot François Duquesnoy, Quellinus had returned to Antwerp in 1640. He had brought with him a new vision of the role of the sculptor. The sculptor was no longer to be an ornamentalist but a creator of a total artwork in which architectural components were replaced by sculptures. He saw the church furniture that he was commissioned to make as an occasion for creating large-scale compositions, incorporated into the church interior.[3] From 1650 onwards, Quellinus worked for fifteen years on the new city hall in Amsterdam together with the lead architect Jacob van Campen. Now called the Royal Palace on the Dam, this construction project, and in particular the marble decorations that Quellinus and his workshop produced, became an example for other buildings in Amsterdam. Quellinus invited many sculptors from his native Antwerp to assist him in the realisation of this project, many of whom such as his cousin Artus Quellinus II, Rombout Verhulst and Bartholomeus Eggers would become leading sculptors in their own right.[4] Grupello may have assisted Quellinus with the sculptural decorations in this project.[2] His exact contributions cannot be identified as this was a collaborative effort. The sculptural decorations in the Amsterdam city hall established the international reputation of Quellinus and his workshop and would lead to many more foreign commissions for the Quellinus workshop including in Germany, Denmark and England. This helped further spread the Flemish Baroque idiom in Europe.[3][5]

He completed a further two years of study in Paris and Versailles, where he was in contact with his compatriots Philippe de Buyster, Gerard van Opstal and Martin Desjardins and learned the technique of bronze casting. He subsequently worked for two years for the sculptor Johan Larson in The Hague.[1]

.jpg.webp)

In Brussels

He returned to Flanders in 1671 and two years later he became a master of the Brussels Guild. He opened a workshop in Brussels, which became very successful and employed many assistants. He enjoyed the patronage of the city as well as that of various European rulers, including the Spanish king Charles II, William II of Orange and Frederick III, the Elector of Brandenburg.[2]

Grupello collaborated from about 1673 to 1678 on the decorative project for the funerary chapel of Duke Lamoral of Thorn and Taxis (in the Our Blessed Lady of Zavel Church in Brussels). This decorative project was initially under the direction of Lucas Faydherbe, a prominent sculptor from Mechelen. Grupello created two allegorical figures representing Hope (Spes) and Faith (Fides), which were placed in niches in the chapel with two other allegorical sculptures of Charity (Caritas) and Truth (Veritas) executed by Jan van Delen.[6] The Charity and Faith (Fides) sculptures were stolen at the end of the 18th century during one of the occupations of the Southern Netherlands by the French. Charity was rediscovered in a French private collection two centuries later and returned to Belgium after a sale at Christie's in 2012.[7] The statue group of Hope (Spes) by Grupello shows a sitting woman personifying hope with an anchor and a child which may be a symbol of the next generation. In other words, the child could represent the son of the Duke of Lamoral who after the early death of his father had to continue the family name and business. The book above Hope refers to the genealogy of the Lamoral family prepared by Jules Chifflet, which had revealed the truth about the family and given a firm basis to the family's claim to its elevated position.[6]

During his time in Brussels, he also fathered a son (born 1671) and a daughter (born 1674) with his mistress Johanna Louisa Quebault (Tebout).[1]

In Germany

In 1695, the Elector Johann Wilhelm appointed Grupello as his official court sculptor and Grupello then moved to live and work in Düsseldorf. He created numerous sculptures of the royal couple in marble and bronze, and was responsible for the supervision of craftsmen who worked on the Elector's palaces. Grupello also designed a fountain known as the Grupello pyramid for the Galerieplatz in Düsseldorf (now in Mannheim).

Grupello married Anna Maria Dautzenberg, the daughter of the Elector's lawyer, in 1698. Five children were born from this marriage.[1] The Elector gave Grupello in 1708 a house in the city centre.[8] The house, which is still called the Grupello-Haus or "Grupello House", is believed to have been designed by the Italian architect Matteo Alberti. Grupello carried out an important reconstruction of the building and used the house as the living quarters of his family and partially also as a studio. Originally, two busts representing the Greek goddesses Artemis and Aphrodite presumed to be by Grupello were placed above the portal of the house. The original bronze statues are now in the local Stadtmuseum Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf and have been replaced by two concrete cast replicas.[9]

.jpg.webp)

With the death of Elector Johann Wilhelm in 1716, the employment of the sculptor at the court came to an end. Elector Johann Wilhelm's successor Elector Carl Philipp introduced austerity measures and dismissed officials and artists. Grupello continued to live in Düsseldorf and in 1619 the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI appointed him as Imperial sculptor.

In 1725, Grupello and his wife moved into the quarters at Ehrenstein Castle in Kerkrade (now in the Netherlands) of their daughter, who was married to an imperial official. He died there in 1730 at the age of 86 years.[1]

Work

Grupello was a versatile artist in terms of the subject range of his sculptures as well as the materials in which he worked. He executed works in marble, ivory and wood and was rare among his contemporary Flemish Baroque sculptors in that he also made bronze statues. A prime example is the bronze equestrian statue of the Elector Johann Wilhelm.

His early work shows a classicist tendency, which may be due to his study period in France. In Brussels, his work was influenced by the Flemish Baroque, and in particular Peter Paul Rubens, and developed into a full-blown Baroque style.[1] A major work that Grupello created in this style in Brussels is the marble wall fountain, intended for the main ballroom of the wholesale fishmongers guild. It is this Baroque style that he brought to Düsseldorf when he moved there. In his later life, he turned more to religious art and produced crucifixes, Madonnas and statues of saints.[1][2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C. J. A. Genders, Gabriël Grupello, in: Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek, Volume 6, p. 392–404, Brussel, Paleis der Akademiën, 1964 (in Dutch)

- 1 2 3 4 Kai Budde. "Grupello, Gabriel." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 6 June 2021

- 1 2 Helena Bussers, De baroksculptuur en het barok Archived 10 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine at Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen (in Dutch)

- ↑ Halsema-Kubes, W. “Bartholomeus Eggers' Keizers- En Keizerinnenbusten Voor Keurvorst Friedrich Wilhelm Van Brandenburg.” Bulletin Van Het Rijksmuseum, vol. 36, no. 1, 1988, pp. 44–53, 6 June 2021

- ↑ Geoffrey Beard. "Gibbons, Grinling." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. Accessed 6 June 2021

- 1 2 Léon Lock, Caritas, Jan van Delen by Erfgoed Koning Boudewijnstichting - Patrimoine Fondation Roi Baudouin, 2013 (in Dutch)

- ↑ Jan van Delen, Caritas at Christie's

- ↑ Grupellohaus Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ↑ Zwei Büsten vervollständigen wieder das Portal am Grupello-Haus (in German)

Further reading

- Rudi Dorsch: Grupello-Pyramide im neuen Glanz. Mannheim 1993.

- Udo Kultermann: Gabriel Grupello. Berlin 1968.

External links

Media related to Gabriel Grupello at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gabriel Grupello at Wikimedia Commons