Fritz Busch | |

|---|---|

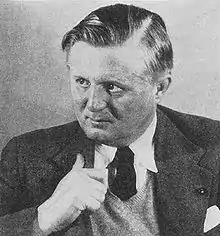

Busch in the early 1930s | |

| Born | 13 March 1890 |

| Died | 14 September 1951 (aged 61) London, England |

| Occupation | Conductor |

Fritz Busch (13 March 1890 – 14 September 1951) was a German conductor.

Busch was born in Siegen to a musical family, and studied at the Cologne Conservatory. After army service in the First World War, he was appointed to senior posts in two German opera houses. At the Stuttgart Opera (1918 to 1922) he modernised the repertory, and at the Dresden State Opera (1922 to 1933) he presented world premieres of operas by Richard Strauss, Ferruccio Busoni, Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill among others. He also conducted at the Bayreuth and Salzburg Festivals.

Being an ardent Anti-Nazi, Busch was dismissed from his post as director at Dresden in 1933 and made most of his later career outside Germany. He conducted in New York and London, but his main bases were Buenos Aires, where he was in charge at the Teatro Colón for several opera seasons in the 1930s and 1940s; Copenhagen and Stockholm, conducting the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Stockholm Philharmonic; and Glyndebourne in England, where he was the founding musical director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera working together with the stage director Carl Ebert.

Busch disliked showmanship, and was known as a scrupulous musician who strove to do justice to the composers whose works he conducted. He died in London aged 61.

Life and career

Early years

Busch was born on 13 March 1890 in Siegen, Westphalia, the eldest of eight children of Wilhelm Busch and his wife Henriette, née Schmidt.[1] Wilhelm was a carpenter, violin-maker and music-shop keeper; his wife was an embroiderer. It was a musical family; Wilhelm and Henriette supplemented their incomes by performing dance music at weekends.[1] Their other children were the violinist Adolf Busch, the actor Willi Busch, the cellist Hermann Busch, and the pianist and composer Heinrich Busch.[2]

As a boy, Busch took music lessons with his father and others, and in 1906 he entered the Cologne Conservatory, studying harmony and counterpoint with Otto Klauwell, piano with Karl Boettcher and later Lazzaro Uzielli, and conducting with the principal, Fritz Steinbach.[2] His relations with Steinbach were edgy, but he acknowledged the older man's influence on him. Steinbach was highly regarded by conductors as different as Arturo Toscanini and Adrian Boult; Busch thought him outstanding as an interpreter of Beethoven, Boult admired his Bach and all three put him at the top of Brahms conductors.[3][4][n 1]

In 1909 Busch spent a season as conductor at the Deutsches Theater, Riga, and in 1911 and 1912 he toured as a pianist.[6] He was then appointed director of music for the city of Aachen with responsibility for the Municipal Opera and the city's celebrated choral society. Among those whose works he premiered there were Donald Tovey, who became a close friend of Busch and his brothers.[7][8] In 1911 Busch married Margarete Boettcher, a niece of his piano teacher;[9] their first son, Hans, later a stage director, was born in 1914.[10]

Busch remained at Aachen until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, when he enlisted in the German army, rising from the ranks to become a junior officer.[11]

Stuttgart and Dresden

In 1918 Busch successfully applied for the vacant post of Württemberg Court Kapellmeister – musical director of the Stuttgart Opera – in succession to Max von Schillings.[12] The conservative tradition of the house, until then the court opera of the Kingdom of Württemberg within the German Empire, was swept away in the November Revolution of 1918,[12] and Busch took advantage of the freedom to widen the repertoire, introducing new works by composers including Hindemith and Pfitzner, and presenting modern stagings such as Adolphe Appia's for Wagner's Ring.[13] In 1922, Busch was appointed musical director of the Dresden State Opera. In the words of The Musical Times:

This was success indeed: a musician in his early thirties raised to the post where Ernst von Schuch himself had conducted the premieres of [Richard Strauss's] Salome, Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier. No opera house in Germany held greater repute. Under Fritz Busch Dresden maintained its lead.[14]

To Dresden's series of Strauss premieres Busch added Intermezzo (1924) and Die ägyptische Helena (1928)). He presented the world premieres of works by Ferruccio Busoni (Doktor Faust, 1925), Paul Hindemith (Cardillac, 1926) and Kurt Weill (Der Protagonist, 1926), and others, and the German premiere of Puccini's Turandot (1926).[14] During his eleven-year tenure he kept the Dresden house at the highest level, mounting innovative, provocative stagings with the help of prominent costume and set designers.[13]

In 1924 Busch conducted Die Meistersinger at the first post-war Bayreuth Festival.[n 2] The production was not a success. The cast was second-rate and there were mixed reviews for the quality of the orchestral playing.[16] Busch refused subsequent requests to conduct at the festival. In 1927, at the invitation of Walter Damrosch, he made his American debut, conducting the New York Symphony Orchestra: the climax of the programme was the nine-year-old Yehudi Menuhin's first performance of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. Busch was so impressed that he arranged for Menuhin to come to Dresden, where he played the Beethoven concerto, the Bach E major and the Brahms.[17]

In 1932 Busch was invited to conduct Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Salzburg Festival. Having recently been much impressed by Carl Ebert's staging of that opera in Berlin, Busch accepted the invitation on condition that Ebert should be engaged as director.[18] The success of the production led Ebert to invite Busch to Berlin to conduct a new staging of Verdi's Un ballo in maschera, a celebrated and long-remembered production.[19]

Though not generally concerned with national or international politics, Busch had watched the rise of the Nazi Party with dismay and disgust. Not himself Jewish, he counted many Jews among his friends, valued democracy and hated dictatorship. He made no secret of his contempt for the Nazis, and after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Busch was dismissed by the Nazi-dominated Saxon Landtag.[20] Among those outraged by the affair was Strauss, whose new opera Arabella, dedicated to Busch, was to have been premiered at the Dresden opera under its dedicatee.[20] Busch was replaced by Karl Böhm, a more congenial figure to the régime.[21]

Although Busch was forced out of Dresden by the local Nazis, the historian Michael Kater writes that senior party figures in Berlin, notably Hermann Göring, had a high regard for Busch and hoped to secure him as general director of the Staatsoper. According to Kater, Wilhelm Furtwängler, chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, did not want so eminent a rival as Busch in the city; as Furtwängler had the backing of Hitler, the post went instead to Clemens Krauss.[7][22] The last offer from the Nazis was a return to Bayreuth to replace Toscanini, who refused to work under the régime. Busch too refused.[23]

Buenos Aires, Copenhagen, Stockholm and Glyndebourne

From 1933 Busch's career was mostly outside Germany. In May of that year he accepted the musical directorship of the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires for a season. Returning to Europe at the end of the year he began a long association with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Stockholm Philharmonic.[7]

In the early 1930s an English landowner, John Christie, and his wife, the singer Audrey Mildmay, conceived the idea of staging country house opera in a purpose-built opera house on the Christie estate at Glyndebourne in Sussex. In November 1933 Christie sounded Busch out about becoming his musical director; Busch was by then contractually committed in Buenos Aires, but a financial crisis in Argentina shortly afterwards enabled him to reconsider Christie's invitation. As at Salzburg, he arranged for Ebert to join him to direct productions.[24]

Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians sums up the success of the Glyndebourne enterprise:

The level achieved by the carefully chosen and rehearsed ensemble at the summer festivals, 1934–1939, is part of operatic history. The repertory was based on Mozart but included Donizetti's Don Pasquale and the first staging by a British company of Verdi's Macbeth. Ironically, it was at patrician Glyndebourne rather than at Dresden that the democratically minded Busch came nearest to his ideal of being able "to build up an opera production in the smallest detail and with ... complete respect for the work'".[7]

Glyndebourne's productions were enthusiastically received by reviewers and public; Busch and his forces made pioneering recordings of Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte for Fred Gaisberg and the Gramophone Company.[25] Both at the time and later two musical idiosyncrasies were commented on: Busch's use of a piano rather than a harpsichord to accompany recitatives and the avoidance of appoggiaturas – in both respects German musical practice being old-fashioned by international standards of the day.[24]

Busch remained musical director at Glyndebourne until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, when the festival was suspended.[26] He made his London debut in 1938, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the Queen's Hall in a programme of Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms.[27]

Busch continued to conduct at the Teatro Colón (1934–1936 and 1940–1947). Until 1940 he worked in Scandinavia during the winter months. According to Grove he grew so attached to Copenhagen that he turned down the offer to become chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic.[7] From June 1940 to 1945 he conducted mostly in South America, except for a not wholly successful Broadway experiment on Glyndebourne lines (the New Opera Company) and guest appearances with the New York Philharmonic, both in 1942. In 1945 he conducted at the Metropolitan Opera, making his debut there with Lohengrin,[2] and toured with the company for four seasons. New York was not to his taste: one concert promoter observed, "he was not a showman".[7]

In 1950 Busch returned to Glyndebourne when the main festival resumed there after the war.[26] Early in 1951 he revisited Germany, conducting in Cologne and Hamburg.[7] He returned to Glyndebourne later in the year for an all-Mozart festival – Così fan tutte, Figaro and Don Giovanni, and the first professional production in England of Idomeneo.[7][24] Howard Taubman of The New York Times praised Ebert's "unflaggingly imaginative and alive" staging and Busch's "loving hand, fusing the orchestra with the singers on the stage into a laughing, glowing entity".[28] In the early post-war years the Glyndebourne company appeared regularly at the Edinburgh Festival, and in August 1951 Busch was in Edinburgh to conduct his first post-war Verdi opera for the company, La forza del destino. Critics praised his "percipient direction" and "inspired" conducting.[29] On 14 September, five days after the last Edinburgh performance, Busch died suddenly of a heart attack in London at the age of 61.[24]

Reputation

In the opinion of Grove, Busch was "the soundest type of German musician: not markedly original or spectacular, but thorough, strong-minded, decisive in intention and execution, with idealism and practical sense nicely balanced".[7] The Times called him "a virile, faithful and extremely skilful interpreter of Mozart" and continued, "His beat like his bearing was one of quiet authority; his interpretations were fully alive without fuss or idiosyncrasy but devoted wholly to the projection of the music as he conceived the composer to have intended it".[11]

Recordings

Busch's recordings include:[30]

- 1934–1935: Mozart, The Marriage of Figaro, with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Roy Henderson, Norman Allin, et al.

- 1935: Mozart, Così fan tutte, with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Heddle Nash, John Brownlee, et al.

- 1936: Mozart, Don Giovanni, with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, John Brownlee, Salvatore Baccaloni, Ina Souez, Roy Henderson, et al.

- 1950: Mozart, Così fan tutte excerpts, with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Sena Jurinac, Richard Lewis, Erich Kunz, Mario Borriello et al.

- 1951: Mozart, Idomeneo excerpts, with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Sena Jurinac, Richard Lewis, Alexander Young

- 1951: Verdi, Un ballo in maschera, in German, Ein Maskenball, with the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Cologne Radio Choir, Lorenz Fehenberger, Martha Mödl, Walburga Wegner, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Anny Schlemm

- 1951: Mozart, Cosi fan tutte Live from Glyndebourne, Jurinac, Howland, Lewis, Bruscantini, Rothmuller, Quensel. 5 July 1951

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ After leaving the Conservatory, Busch developed a warm friendship with Steinbach, who became godfather to Busch's first child, Hans Peter, in 1914.[5]

- ↑ On his arrival in Bayreuth, Busch decided to attend a chorus rehearsal that was in progress, only to be dragooned into the tenor section by the chorus master Hugo Rüdel who had mistaken him for a member of the choir.[15]

References

- 1 2 Busch 1953, pp. 13, 33

- 1 2 3 Slonimsky, Kuhn & McIntire 2001, pp. 516–517

- ↑ Boult 1973, p. 181.

- ↑ Busch 1953, pp. 48, 57.

- ↑ Dyment 2012, p. 312.

- ↑ Randel 1996, pp. 120–121

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Crichton 2001

- ↑ Boult 1983, p. 153.

- ↑ Busch 1953, p. 86.

- ↑ Tommasini, Anthony (29 September 1996). "Hans Busch, 82, Stage Director of the Indiana University Opera". The New York Times.

- 1 2 "Dr Fritz Busch", The Times, 17 September 1951, p. 6

- 1 2 Busch 1953, p. 119.

- 1 2 Stevenson, Joseph. Fritz Busch at AllMusic. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- 1 2 Aber 1951, pp. 499–500

- ↑ Busch 1953, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ "Bayreuth Festival", The Times, 26 July 1924, p. 10; and Busch 1953, p. 164

- ↑ Busch 1953, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Busch 1953, p. 189.

- ↑ Busch 1953, pp. 189–190.

- 1 2 Kater 1999, p. 121

- ↑ Kater 1999, p. 65.

- ↑ Kater 1999, p. 122

- ↑ Busch 1953, p. 217.

- 1 2 3 4 Hughes 1984, pp. 253, 255–258

- ↑ Blyth 1979, pp. 44, 88, 104.

- 1 2 Sadie, Stanley. "Glyndebourne", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 24 May 2020 (subscription required)

- ↑ "London Symphony Orchestra", The Times, 29 November 1938, p. 12

- ↑ Taubman, Howard. "3rd Mozart Opera at Glyndebourne", The New York Times, 28 June 1951, p. 36

- ↑ "Glyndebourne Opera", The Times, 22 August 1951, p. 2; and "Edinburgh Festival", The Stage, 30 August 1951, p. 10

- ↑ Fritz Busch discography (in German)

Sources

- Aber, Adolf (November 1951). "Fritz Busch, 1890–1951". The Musical Times. 92 (1305): 499–500. JSTOR 935420.(subscription required)

- Blyth, Alan (1979). Opera on Record. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-139980-1.

- Boult, Adrian (1973). My Own Trumpet. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-02445-4.

- Boult, Adrian (1983). Boult on Music. London: Toccata. ISBN 978-0-907689-03-4.

- Busch, Fritz (1953). Pages from a Musician's Life. Translated by Marjorie Strachey. London: Hogarth Press. OCLC 721199777. Originally published in 1949 as Aus dem Leben eines Musikers.

- Crichton, Ronald (2001). "Busch, Fritz". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.04423. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 24 May 2020. (subscription required)

- Dyment, Christopher (2012). Toscanini in Britain. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-84383-789-3.

- Hughes, Spike (May 1984). "The Heartbeat of the Performance". The Musical Times. 125 (1695): 253, 255–258. doi:10.2307/961561. JSTOR 961561.

- Kater, Michael (1999). The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513242-7.

- Randel, Don (1996). The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674372993. OCLC 1023745280.

- Slonimsky, Nicholas; Kuhn, Laura; McIntire, Dennis (2001). "Busch, Fritz". In Laura Kuhn (ed.). Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (8th ed.). New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-866091-2.

External links

Media related to Fritz Busch at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fritz Busch at Wikimedia Commons- Fritz Busch – Profile at The Remington Site