| Frederick the Great | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

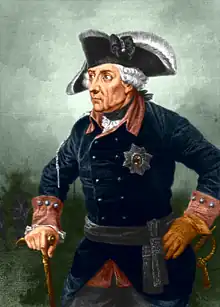

.jpg.webp) Portrait by Johann Georg Ziesenis (1763) | |||||

| Reign | 31 May 1740 – 17 August 1786 | ||||

| Predecessor | Frederick William I | ||||

| Successor | Frederick William II | ||||

| Born | 24 January 1712 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia | ||||

| Died | 17 August 1786 (aged 74) Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia | ||||

| Burial | Sanssouci, Potsdam | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Hohenzollern | ||||

| Father | Frederick William I of Prussia | ||||

| Mother | Sophia Dorothea of Hanover | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

| Prussian Royalty |

| House of Hohenzollern |

|---|

|

| Frederick William I |

|

| Frederick II |

Frederick II (German: Friedrich II.; 24 January 1712 – 17 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Silesian wars, his reorganisation of the Prussian Army, the First Partition of Poland, and his patronage of the arts and the Enlightenment. Frederick was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled King in Prussia, declaring himself King of Prussia after annexing Royal Prussia from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772. Prussia greatly increased its territories and became a major military power in Europe under his rule. He became known as Frederick the Great (German: Friedrich der Große) and was nicknamed "Old Fritz" (German: der Alte Fritz).

In his youth, Frederick was more interested in music and philosophy than in the art of war, which led to clashes with his authoritarian father, Frederick William I of Prussia. However, upon ascending to the Prussian throne, he attacked and annexed the rich Austrian province of Silesia in 1742, winning military acclaim for himself and Prussia. He became an influential military theorist whose analyses emerged from his extensive personal battlefield experience and covered issues of strategy, tactics, mobility and logistics.

Frederick was a supporter of enlightened absolutism, stating that the ruler should be the first servant of the state. He modernised the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service, and pursued religious policies throughout his realm that ranged from tolerance to segregation. He reformed the judicial system and made it possible for men of lower status to become judges and senior bureaucrats. Frederick also encouraged immigrants of various nationalities and faiths to come to Prussia, although he enacted oppressive measures against Catholics in Silesia and Polish Prussia. He supported the arts and philosophers he favoured, and allowed freedom of the press and literature. Frederick was almost certainly homosexual, and his sexuality has been the subject of much study. Because he died childless, he was succeeded by his nephew, Frederick William II. He is buried at his favourite residence, Sanssouci in Potsdam.

Nearly all 19th-century German historians made Frederick into a romantic model of a glorified warrior, praising his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to duty and success in building Prussia into a great power in Europe. Frederick remained an admired historical figure through Germany's defeat in World War I, and the Nazis glorified him as a great German leader prefiguring Adolf Hitler, who personally idolised him. His reputation became less favourable in Germany after World War II, partly due to his status as a Nazi symbol. Historians in the 21st century tend to view Frederick as an outstanding military leader and capable monarch, whose commitment to enlightenment culture and administrative reform built the foundation that allowed the Kingdom of Prussia to contest the Austrian Habsburgs for leadership among the German states.

Early life

Frederick was the son of then-Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Hanover.[1] He was born sometime between 11 and 12 p.m. on 24 January 1712 in the Berlin Palace and was baptised with the single name Friedrich by Benjamin Ursinus von Bär on 31 January.[2] The birth was welcomed by his grandfather, Frederick I, as his two previous grandsons had both died in infancy. With the death of Frederick I in 1713, his son Frederick William I became King in Prussia, thus making young Frederick the crown prince. Frederick had nine siblings who lived to adulthood. He had six sisters. The eldest was Wilhelmine, who became his closest sibling.[3] He also had three younger brothers, including Augustus William and Henry.[4] The new king wished for his children to be educated not as royalty, but as simple folk. They were tutored by a French woman, Madame de Montbail, who had also educated Frederick William.[5]

Frederick William I, popularly dubbed the "Soldier King", had created a large and powerful army that included a regiment of his famous "Potsdam Giants"; he carefully managed the kingdom's wealth and developed a strong centralised government. He also had a violent temper and ruled Brandenburg-Prussia with absolute authority.[6] In contrast, Frederick's mother Sophia, whose father, George Louis of Brunswick-Lüneburg, had succeeded to the British throne as King George I in 1714, was polite, charismatic and learned.[7] The political and personal differences between Frederick's parents created tensions,[8] which affected Frederick's attitude toward his role as a ruler, his attitude toward culture, and his relationship with his father.[9]

During his early youth, Frederick lived with his mother and sister Wilhelmine,[9] although they regularly visited their father's hunting lodge at Königs Wusterhausen.[10] Frederick and his older sister formed a close relationship,[9] which lasted until her death in 1758.[11] Frederick and his sisters were brought up by a Huguenot governess and tutor and learned French and German simultaneously. Undeterred by his father's desire that his education be entirely religious and pragmatic, the young Frederick developed a preference for music, literature, and French culture. Frederick Wilhelm thought these interests were effeminate,[12] as they clashed with his militarism, resulting in his frequent beating and humiliation of Frederick.[13] Nevertheless, Frederick, with the help of his tutor in Latin, Jacques Duhan, procured for himself a 3,000 volume secret library of poetry, Greek and Roman classics, and philosophy to supplement his official lessons.[14]

Although his father, Frederick William I, had been raised a Calvinist in spite of the Lutheran state faith in Prussia, he feared he was not one of God's elect. To avoid the possibility of his son Frederick being motivated by the same concerns, the king ordered that his heir not be taught about predestination. Despite his father's intention, Frederick appeared to have adopted a sense of predestination for himself.[15]

Crown Prince

At age 16, Frederick formed an attachment to the king's 17-year-old page, Peter Karl Christoph von Keith. Wilhelmine recorded that the two "soon became inseparable. Keith was intelligent, but without education. He served my brother from feelings of real devotion, and kept him informed of all the king's actions."[16] Wilhelmine would further record that "Though I had noticed that he was on more familiar terms with this page than was proper in his position, I did not know how intimate the friendship was." As Frederick was almost certainly homosexual,[17] his relationship with Keith may have been homoerotic, although the extent of their intimacy remains ambiguous.[18] When Frederick William heard rumours of their relationship, Keith was sent away to an unpopular regiment near the Dutch frontier.[19]

In the mid-1720s, Queen Sophia Dorothea attempted to arrange the marriage of Frederick and his sister Wilhelmine to her brother King George II's children Amelia and Frederick, who was the heir apparent.[20] Fearing an alliance between Prussia and Great Britain, Field Marshal von Seckendorff, the Austrian ambassador in Berlin, bribed the Prussian Minister of War, Field Marshal von Grumbkow, and the Prussian ambassador in London, Benjamin Reichenbach. The pair undermined the relationship between the British and Prussian courts using bribery and slander.[21] Eventually Frederick William became angered by the idea of the effete Frederick being married to an English wife and under the influence of the British court.[22] Instead, he signed a treaty with Austria, which vaguely promised to acknowledge Prussia's rights to the principalities of Jülich-Berg, which led to the collapse of the marriage proposal.[23]

Katte affair

Soon after his relationship with Keith ended, Frederick became close friends with Hans Hermann von Katte, a Prussian officer several years older than Frederick who became one of his boon companions and may have been his lover.[24] After the English marriages became impossible, Frederick plotted to flee to England with Katte and other junior army officers.[25] While the royal retinue was near Mannheim in the Electorate of the Palatinate, Robert Keith, who was Peter Keith's brother and also one of Frederick's companions, had an attack of conscience when the conspirators were preparing to escape and begged Frederick William for forgiveness on 5 August 1730.[26] Frederick and Katte were subsequently arrested and imprisoned in Küstrin. Because they were army officers who had tried to flee Prussia for Great Britain, Frederick William levelled an accusation of treason against the pair. The king briefly threatened the crown prince with execution, then considered forcing Frederick to renounce the succession in favour of his brother, Augustus William, although either option would have been difficult to justify to the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire.[27] The king condemned Katte to death and forced Frederick to watch his beheading at Küstrin on 6 November, leading the crown prince to faint just before the fatal blow.[28]

Frederick was granted a royal pardon and released from his cell on 18 November 1730, although he remained stripped of his military rank.[29] Rather than being permitted to return to Berlin, he was forced to remain in Küstrin and began rigorous schooling in statecraft and administration for the War and Estates Departments. Tensions eased slightly when Frederick William visited Küstrin a year later, and Frederick was allowed to visit Berlin on the occasion of his sister Wilhelmine's marriage to Margrave Frederick of Bayreuth on 20 November 1731.[30] The crown prince returned to Berlin after finally being released from his tutelage at Küstrin on 26 February 1732 on condition that he marry Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern.[31]

Marriage and War of the Polish Succession

Initially, Frederick William considered marrying Frederick to Elisabeth of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the niece of Empress Anna of Russia, but this plan was ardently opposed by Prince Eugene of Savoy. Frederick himself also proposed marrying Maria Theresa of Austria in return for renouncing the succession.[32] Instead, Eugene persuaded Frederick William, through Seckendorff, that the crown prince should marry Elisabeth Christine, who was a Protestant relative of the Austrian Habsburgs.[33] Frederick wrote to his sister that, "There can be neither love nor friendship between us",[34] and he threatened suicide,[35] but he went along with the wedding on 12 June 1733. He had little in common with his bride, and the marriage was resented as an example of the Austrian political interference that had plagued Prussia.[36] Nevertheless, during their early married life, the royal couple resided at the Crown Prince's Palace in Berlin. Later, Elisabeth Christine accompanied Frederick to Schloss Rheinsberg, where at this time she played an active role in his social life.[37] After his father died and he had secured the throne, Frederick separated from Elisabeth. He granted her the Schönhausen Palace and apartments at the Berliner Stadtschloss, but he prohibited Elisabeth Christine from visiting his court in Potsdam. Frederick and Elisabeth Christine had no children, and Frederick bestowed the title of the heir to the throne, "Prince of Prussia", on his brother Augustus William. Nevertheless, Elisabeth Christine remained devoted to him. Frederick gave her all the honours befitting her station, but never displayed any affection. After their separation, he would only see her on state occasions.[38] These included visits to her on her birthday and were some of the rare occasions when Frederick did not wear military uniform.[39]

In 1732, Frederick was restored to the Prussian Army as Colonel of the Regiment von der Goltz, stationed near Nauen and Neuruppin.[40] When Prussia provided a contingent of troops to aid the Army of the Holy Roman Empire during the War of the Polish Succession, Frederick studied under Prince Eugene of Savoy during the campaign against France on the Rhine;[41] he noted the weakness of the Imperial Army under Eugene's command, something that he would capitalise on at Austria's expense when he later took the throne.[42] Frederick William, weakened by gout and seeking to reconcile with his heir, granted Frederick Schloss Rheinsberg in Rheinsberg, north of Neuruppin. At Rheinsberg, Frederick assembled a small number of musicians, actors and other artists. He spent his time reading, watching and acting in dramatic plays, as well as composing and playing music.[43] Frederick formed the Bayard Order to discuss warfare with his friends; Heinrich August de la Motte Fouqué was made the grand master of the gatherings.[44] Later, Frederick regarded this time as one of the happiest of his life.[45]

Reading and studying the works of Niccolò Machiavelli, such as The Prince, was considered necessary for any king in Europe to rule effectively. In 1739, Frederick finished his Anti-Machiavel, an idealistic rebuttal of Machiavelli. It was written in French—as were all of Frederick's works—and published anonymously in 1740, but Voltaire distributed it in Amsterdam to great popularity.[46] Frederick's years dedicated to the arts instead of politics ended upon the 1740 death of Frederick William and his inheritance of the Kingdom of Prussia. Frederick and his father were more or less reconciled at the latter's death, and Frederick later admitted, despite their constant conflict, that Frederick William had been an effective ruler: "What a terrible man he was. But he was just, intelligent, and skilled in the management of affairs... it was through his efforts, through his tireless labour, that I have been able to accomplish everything that I have done since."[47]

Inheritance

In one defining respect Frederick would come to the throne with an exceptional inheritance. Frederick William I had left him with a highly militarised state. Prussia was the twelfth largest country in Europe in terms of population, but its army was the fourth largest: only the armies of France, Russia and Austria were larger.[48] Prussia had one soldier for every 28 citizens, whereas Great Britain only had one for every 310, and the military absorbed 86% of Prussia's state budget.[49] Moreover, the Prussian infantry trained by Frederick William I were, at the time of Frederick's accession, arguably unrivalled in discipline and firepower. By 1770, after two decades of punishing war alternating with intervals of peace, Frederick had doubled the size of the huge army he had inherited. The situation is summed up in a widely translated and quoted aphorism attributed to Mirabeau, who asserted in 1786 that "La Prusse n'est pas un pays qui a une armée, c'est une armée qui a un pays"[50] ("Prussia was not a state in possession of an army, but an army in possession of a state").[51] By using the resources his frugal father had cultivated, Frederick was eventually able to establish Prussia as the fifth and smallest European great power.[52]

Prince Frederick was twenty-eight years old when his father Frederick William I died and he ascended to the throne of Prussia.[53] Before his accession, Frederick was told by D'Alembert, "The philosophers and the men of letters in every land have long looked upon you, Sire, as their leader and model."[54] Such devotion, consequently, had to be tempered by political realities. When Frederick ascended the throne as the third "King in Prussia" in 1740, his realm consisted of scattered territories, including Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg in the west of the Holy Roman Empire; Brandenburg, Hither Pomerania, and Farther Pomerania in the east of the Empire; and the Kingdom of Prussia, the former Duchy of Prussia, outside of the Empire bordering the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was titled King in Prussia because his kingdom included only part of historic Prussia; he was to declare himself King of Prussia after the First Partition of Poland in 1772.[55]

Reign

Frederick the Great

War of the Austrian Succession

When Frederick became king, he was faced with the challenge of overcoming Prussia's weaknesses, vulnerably disconnected holdings with a weak economic base.[56] To strengthen Prussia's position, he fought wars mainly against Austria, whose Habsburg dynasty had reigned as Holy Roman Emperors continuously since the 15th century.[57] Thus, upon succeeding to the throne on 31 May 1740,[58] Frederick declined to endorse the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, a legal mechanism to ensure the inheritance of the Habsburg domains by Maria Theresa of Austria, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. Upon the death of Charles VI on 29 October 1740,[59] Frederick disputed the 23-year-old Maria Theresa's right of succession to the Habsburg lands, while simultaneously asserting his own right to the Austrian province of Silesia based on a number of old, though ambiguous, Hohenzollern claims to parts of Silesia.[60]

Accordingly, the First Silesian War (1740–1742, part of the War of the Austrian Succession) began on 16 December 1740 when Frederick invaded and quickly occupied almost all of Silesia within seven weeks.[53] Though Frederick justified his occupation on dynastic grounds,[61] the invasion of this militarily and politically vulnerable part of the Habsburg empire also had the potential to provide substantial long-term economic and strategic benefits.[62] The occupation of Silesia added one of the most densely industrialised German regions to Frederick's kingdom and gave it control over the navigable Oder River.[63] It nearly doubled Prussia's population and increased its territory by a third.[64] It also prevented Augustus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, from seeking to connect his own disparate lands through Silesia.[65]

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15767.tif.jpg.webp)

In late March 1741, Frederick set out on campaign again to capture the few remaining fortresses within the province that were still holding out. He was surprised by the arrival of an Austrian army, which he fought at the Battle of Mollwitz on 10 April 1741.[66] Though Frederick had served under Prince Eugene of Savoy, this was his first major battle in command of an army. In the course of the fighting, Frederick's cavalry was disorganised by a charge of the Austrian horse. Believing his forces had been defeated, Frederick galloped away to avoid capture,[67] leaving Field Marshal Kurt Schwerin in command to lead the disciplined Prussian infantry to victory. Frederick would later admit to humiliation at his abdication of command[68] and would state that Mollwitz was his school.[69] Disappointed with the performance of his cavalry, whose training his father had neglected in favour of the infantry, Frederick spent much of his time in Silesia establishing a new doctrine for them.[70]

Encouraged by Frederick's victory at Mollwitz, the French and their ally, the Electorate of Bavaria, entered the war against Austria in early September 1741 and marched on Prague.[71] Meanwhile, Frederick, as well as other members of the League of Nymphenburg, sponsored the candidacy of his ally Charles of Bavaria to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. In late November, the Franco-Bavarian forces took Prague, and Charles was crowned King of Bohemia.[72] Subsequently, he was elected as the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII on 24 January 1742. After the Austrians pulled their army out of Silesia to defend Bohemia, Frederick pursued them and blocked their path to Prague.[73] The Austrians counter-attacked on 17 May 1742, initiating the Battle of Chotusitz. In this battle, Frederick's retrained cavalry proved more effective than at Mollwitz,[74] but once more it was the discipline of the Prussian infantry that won the field[75] and allowed Frederick to claim a major victory.[76] This victory, along with the Franco-Bavarian forces capturing Prague, forced the Austrians to seek peace. The terms of the Treaty of Breslau between Austria and Prussia, negotiated in June 1742, gave Prussia all of Silesia and Glatz County, with the Austrians retaining only the portion called Austrian or Czech Silesia.[77]

By 1743, the Austrians had subdued Bavaria and driven the French out of Bohemia. Frederick strongly suspected Maria Theresa would resume war in an attempt to recover Silesia. Accordingly, he renewed his alliance with France and preemptively invaded Bohemia in August 1744, beginning the Second Silesian War.[78] In late August 1744, Frederick's army had crossed the Bohemian frontier, marched directly to Prague, and laid siege to the city, which surrendered on 16 September 1744 after a three-day bombardment.[79] Frederick's troops immediately continued marching into the heart of central Bohemia,[68] but Saxony had now joined the war against Prussia.[80] Although the combined Austrian and Saxon armies outnumbered Frederick's forces, they refused to directly engage with Frederick's army, harassing his supply lines instead. Eventually, Frederick was forced to withdraw to Silesia as winter approached.[81] In the interim, Frederick also successfully claimed his inheritance to the minor territory of East Frisia on the North Sea coast of Germany, occupying the territory after its last ruler died without issue in 1744.[82]

In January 1745, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII of Bavaria died,[83] taking Bavaria out of the war and allowing Maria Theresa's husband Francis of Lorraine to be eventually elected Holy Roman Emperor.[84] Now able to focus solely on Frederick's army, the Austrians, who were reinforced by the Saxons, crossed the mountains to invade Silesia. After allowing them across,[lower-alpha 1] Frederick pinned them down and decisively defeated them at the Battle of Hohenfriedberg on 4 June 1745.[86] Frederick subsequently advanced into Bohemia and defeated a counterattack by the Austrians at the Battle of Soor.[87] Frederick then turned towards Dresden when he learned the Saxons were preparing to march on Berlin. However, on 15 December 1745, Prussian forces under the command of Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau soundly defeated the Saxons at the Battle of Kesselsdorf.[88] After linking up his army with Leopold's, Frederick occupied the Saxon capitol of Dresden, forcing the Saxon elector, Augustus III, to capitulate.[89]

Once again, Frederick's victories on the battlefield compelled his enemies to sue for peace. Under the terms of the Treaty of Dresden, signed on 25 December 1745, Austria was forced to adhere to the terms of the Treaty of Breslau giving Silesia to Prussia.[90] It was after the signing of the treaty that Frederick, then 33 years old, first became known as "the Great".[91]

Seven Years' War

Though Frederick had withdrawn from the War of the Austrian Succession once Austria guaranteed his possession of Silesia,[92] Austria remained embroiled in the war until the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. Less than a year after the treaty was signed, Maria Theresa was once more seeking allies, particularly Russia and France, to eventually renew the war with Prussia to regain Silesia.[93] In preparation for a new confrontation with Frederick, the Empress reformed Austria's tax system and military.[94] During the ten years of peace that followed the signing of the Treaty of Dresden, Frederick also prepared to defend his claim on Silesia by further fortifying the province and expanding his army,[95] as well as reorganising his finances.[96]

In 1756, Frederick attempted to forestall Britain's financing of a Russian army on Prussia's border by negotiating an alliance with Britain at the Convention of Westminster, by which Prussia would protect Hanover against French attack, and Britain would no longer subsidise Russia. This treaty triggered the Diplomatic Revolution in which Habsburg Austria and Bourbon France, who had been traditional enemies, allied together with Russia to defeat the Anglo-Prussian coalition.[97] To strengthen his strategic position against this coalition,[98] on 29 August 1756, Frederick's well-prepared army preemptively invaded Saxony.[99] His invasion triggered the Third Silesian War and the larger Seven Years' War, both of which lasted until 1763. He quickly captured Dresden, besieged the trapped Saxon army in Pirna, and continued marching the remainder of his army toward North Bohemia, intending to winter there.[100] At the Battle of Lobositz he claimed a close victory against an Austrian army that was aiming to relieve Pirna,[101] but afterward withdrew his forces back to Saxony for the winter.[102] When the Saxon forces in Pirna finally capitulated in October 1756, Frederick forcibly incorporated them into his own army.[103] This action, along with his initial invasion of neutral Saxony brought him widespread international criticism;[104] but the conquest of Saxony also provided him with significant financial, military, and strategic assets that helped him sustain the war.[105]

In the early spring of 1757, Frederick once more invaded Bohemia.[106] He was victorious against the Austrian army at the Battle of Prague on 6 May 1757, but his losses were so great he was unable to take the city itself, and settled for besieging it instead.[107] A month later on 18 June 1757, Frederick suffered his first major defeat at the Battle of Kolín,[108] which forced him to abandon his invasion of Bohemia. When the French and the Austrians pursued him into Saxony and Silesia in the fall of 1757, Frederick defeated and repulsed a much larger Franco-Austrian army at the Battle of Rossbach[109] and another Austrian army at the Battle of Leuthen.[110] Frederick hoped these two victories would force Austria to negotiate, but Maria Theresa was determined not to make peace until she had recovered Silesia, and the war continued.[111] Despite its strong performance, the losses suffered from combat, disease and desertion had severely reduced the quality of the Prussian army.[112]

In the remaining years of the war, Frederick faced a coalition of enemies including Austria, France, Russia, Sweden, and the Holy Roman Empire,[113] supported only by Great Britain and its allies Hesse, Brunswick, and Hanover.[114] In 1758 Frederick once more took the initiative by invading Moravia. By May, he had laid siege to Olomouc; but, the Austrians were able to hold the town and destroyed Frederick's supply train, forcing him to retreat into Silesia.[115] In the meantime, the Russian army had advanced within 100 miles (160 km) east of Berlin. In August, he fought the Russian forces to a draw at the Battle of Zorndorf, in which nearly a third of Frederick's soldiers were casualties.[116] He then headed south to face the Austrian army in Saxony. There, he was defeated at the Battle of Hochkirch on 14 October, although the Austrian forces were not able to exploit their victory.[117]

During the 1759 campaign, the Austrian and Russian forces took the initiative, which they kept for the remainder of the war.[118] They joined and once more advanced on Berlin. Frederick's army, which consisted of a substantial number of quickly recruited, half-trained soldiers,[119] attempted to check them at the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12 August, where he was defeated and his troops were routed.[120] Almost half his army was destroyed, and Frederick almost became a casualty when a bullet smashed a snuffbox he was carrying.[121] Nevertheless, the Austro-Russian forces hesitated and stopped their advance for the year, an event Frederick later called the "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg".[122] Frederick spent the remainder of the year in a futile attempt to manoeuvre the Austrians out of Saxony, where they had recaptured Dresden. [123] His effort cost him further losses when his general Friedrich August von Finck capitulated at Maxen on 20 November.[124]

At the beginning of 1760, the Austrians moved to retake Silesia, where Frederick defeated them at the Battle of Liegnitz on 15 August.[125] The victory did not allow Frederick to regain the initiative or prevent Russian and Austrian troops from raiding Berlin in October to extort a ransom from the city.[126] At the end of the campaign season, Frederick fought his last major engagement of the war.[127] He won a marginal victory at the Battle of Torgau on 3 November,[128] which secured Berlin from further raids.[129] In this battle, Frederick became a casualty when he was hit in the chest by a spent bullet.[130]

By 1761, both the Austrian and Prussian military forces were so exhausted that no major battles were fought between them. Frederick's position became even more desperate in 1761 when Britain, having achieved victory in the American and Indian theatres of the war, ended its financial support for Prussia after the death of King George II, Frederick's uncle.[131] The Russian forces also continued their advance, occupying Pomerania and parts of Brandenburg. With the Russians slowly advancing towards Berlin, it looked as though Prussia was about to collapse.[132] On 6 January 1762, Frederick wrote to Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, "We ought now to think of preserving for my nephew, by way of negotiation, whatever fragments of my territory we can save from the avidity of my enemies".[133]

The sudden death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia in January 1762 led to the succession of the Prussophile Peter III, her German nephew, who was also the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp.[134] This led to the collapse of the anti-Prussian coalition; Peter immediately promised to end the Russian occupation of East Prussia and Pomerania, returning them to Frederick. One of Peter III's first diplomatic endeavours was to seek a Prussian title; Frederick obliged. Peter III was so enamoured of Frederick that he not only offered him the full use of a Russian corps for the remainder of the war against Austria, he also wrote to Frederick that he would rather have been a general in the Prussian army than Tsar of Russia.[135] More significantly, Russia's about-face from an enemy of Prussia to its patron rattled the leadership of Sweden, who hastily made peace with Frederick as well.[136] With the threat to his eastern borders over, and France also seeking peace after its defeats by Britain, Frederick was able to fight the Austrians to a stalemate and finally brought them to the peace table. While the ensuing Treaty of Hubertusburg simply returned the European borders to what they had been before the Seven Years' War, Frederick's ability to retain Silesia in spite of the odds earned Prussia admiration throughout the German-speaking territories. A year following the Treaty of Hubertusburg, Catherine the Great, Peter III's widow and usurper, signed an eight-year alliance with Prussia, albeit with conditions that favoured the Russians.[137]

Frederick's ultimate success in the Seven Years' War came at a heavy financial cost to Prussia. Part of the burden was covered by the Anglo-Prussian Convention, which gave Frederick an annual £670,000 in British subsidies from 1758 till 1762.[138] These subsidies ceased when Frederick allied with Peter III,[139] partly because of the changed political situation[140] and also because of Great Britain's decreasing willingness to pay the sums Frederick wanted.[141] Frederick also financed the war by devaluing the Prussian coin five times; debased coins were produced with the help of Leipzig mintmasters, Veitel Heine Ephraim, Daniel Itzig and Moses Isaacs.[142] He also debased the coinage of Saxony and Poland.[143] This debasement of the currency helped Frederick cover over 20 per cent of the cost of the war, but at the price of causing massive inflation and economic upheaval throughout the region.[144] Saxony, occupied by Prussia for most of the conflict, was left nearly destitute as a result.[145] While Prussia lost no territory, the population and army were severely depleted by constant combat and invasions by Austria, Russia and Sweden. The best of Frederick's officer corps were also killed in the conflict. Although Frederick managed to bring his army up to 190,000 men by the time the economy had largely recovered in 1772, which made it the third-largest army in Europe, almost none of the officers in this army were veterans of his generation and the King's attitude towards them was extremely harsh.[146] During this time, Frederick also suffered a number of personal losses. Many of his closest friends and family members—including his brother Augustus William,[147] his sister Wilhelmine, and his mother—had died while Frederick was engaged in the war.[148]

First Partition of Poland

Frederick sought to acquire and economically exploit Polish Prussia as part of his wider aim of enriching his kingdom.[149] As early as 1731 Frederick had suggested that his country would benefit from annexing Polish territory,[150] and had described Poland as an "artichoke, ready to be consumed leaf by leaf".[151] By 1752, he had prepared the ground for the partition of Poland–Lithuania, aiming to achieve his goal of building a territorial bridge between Pomerania, Brandenburg, and his East Prussian provinces.[152] The new territories would also provide an increased tax base, additional populations for the Prussian military, and serve as a surrogate for the other overseas colonies of the other great powers.[153]

Poland was vulnerable to partition due to poor governance, as well as the interference of foreign powers in its internal affairs.[154] Frederick himself was partly responsible for this weakness by opposing attempts at financial and political reform in Poland,[149] and undermining the Polish economy by inflating its currency by his use of Polish coin dies. The profits exceeded 25 million thalers, twice the peacetime national budget of Prussia.[155] He also thwarted Polish efforts to create a stable economic system by building a customs fort at Marienwerder on the Vistula, Poland's major trade artery,[149] and by bombarding Polish customs ports on the Vistula.[156]

Frederick also used Poland's religious dissension to keep the kingdom open to Prussian control.[157] Poland was predominantly Roman Catholic, but approximately ten per cent of Poland's population, 600,000 Eastern Orthodox and 250,000 Protestants, were non-Catholic dissenters. During the 1760s, the dissenters' political importance was out of proportion to their numbers. Although dissenters still had substantial rights, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had increasingly been reducing their civic rights after a period of considerable religious and political freedom.[158] Soon Protestants were barred from public offices and the Sejm (Polish Parliament).[159] Frederick took advantage of this situation by becoming the protector of Protestant interests in Poland in the name of religious freedom.[160] Frederick further opened Prussian control by signing an alliance with Catherine the Great who placed Stanisław August Poniatowski, a former lover and favourite, on the Polish throne.[161]

After Russia occupied the Danubian Principalities in 1769–70, Frederick's representative in Saint Petersburg, his brother Prince Henry, convinced Frederick and Maria Theresa that the balance of power would be maintained by a tripartite division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth instead of Russia taking land from the Ottomans. They agreed to the First Partition of Poland in 1772, which took place without war. Frederick acquired most of Royal Prussia, annexing 38,000 square kilometres (15,000 sq mi) and 600,000 inhabitants. Although Frederick's share of the partition was the smallest of the partitioning powers, the lands he acquired had roughly the same economic value as the others and had great strategic value.[162] The newly created province of West Prussia connected East Prussia and Farther Pomerania and granted Prussia control of the mouth of the Vistula River, as well as cutting off Poland's sea trade. Maria Theresa had only reluctantly agreed to the partition, to which Frederick sarcastically commented, "she cries, but she takes".[163]

Frederick undertook the exploitation of Polish territory under the pretext of an enlightened civilising mission that emphasised the supposed cultural superiority of Prussian ways.[164] He saw Polish Prussia as barbaric and uncivilised,[165] describing the inhabitants as "slovenly Polish trash"[166] and comparing them unfavourably with the Iroquois.[163] His long-term goal was to remove the Poles through Germanisation, which included appropriating Polish Crown lands and monasteries,[167] introducing a military draft, encouraging German settlement in the region, and implementing a tax policy that disproportionately impoverished Polish nobles.[168]

War of the Bavarian Succession

Late in his life Frederick involved Prussia in the low-scale War of the Bavarian Succession in 1778, in which he stifled Austrian attempts to exchange the Austrian Netherlands for Bavaria.[169] For their part, the Austrians tried to pressure the French to participate in the War of Bavarian Succession since there were guarantees under consideration related to the Peace of Westphalia, clauses which linked the Bourbon dynasty of France and the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty of Austria. Unfortunately for the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, the French court was unwilling to support him because they were already supporting the American revolutionaries on the North American continent and the idea of an alliance with Austria had been unpopular in France since the end of the Seven Years' War.[170] Frederick ended up as a beneficiary of the American Revolutionary War, as Austria was left more or less isolated.[171]

Moreover, Saxony and Russia, both of which had been Austria's allies in the Seven Years' War, were now allied with Prussia.[172] Although Frederick was weary of war in his old age, he was determined not to allow Austrian dominance in German affairs.[173] Frederick and Prince Henry marched the Prussian army into Bohemia to confront Joseph's army, but the two forces ultimately descended into a stalemate, largely living off the land and skirmishing rather than actively attacking each other.[174] Frederick's longtime rival Maria Theresa, who was Joseph's mother and his co-ruler, did not want a new war with Prussia, and secretly sent messengers to Frederick to discuss peace negotiations.[175] Finally, Catherine II of Russia threatened to enter the war on Frederick's side if peace was not negotiated, and Joseph reluctantly dropped his claim to Bavaria.[176] When Joseph tried the scheme again in 1784, Frederick created the Fürstenbund (League of Princes), allowing himself to be seen as a defender of German liberties, in contrast to his earlier role of attacking the imperial Habsburgs. To stop Joseph II's attempts to acquire Bavaria, Frederick enlisted the help of the Electors of Hanover and Saxony along with several other minor German princes. Perhaps even more significant, Frederick benefited from the defection of the senior prelate of the German Church, the Archbishop of Mainz, who was also the arch-chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire, which further strengthened Frederick and Prussia's standing amid the German states.[177]

Policies

Administrative modernisation

In his earliest published work, the Anti-Machiavel,[178] and his later Testament politique (Political Testament),[179] Frederick wrote that the sovereign was the first servant of the state.[lower-alpha 2] Acting in this role, Frederick helped transform Prussia from a European backwater to an economically strong and politically reformed state.[182] He protected his industries with high tariffs and minimal restrictions on domestic trade. He increased the freedom of speech in press and literature,[183] abolished most uses of judicial torture,[184] and reduced the number of crimes that could be punished by the death sentence.[185] Working with his Grand Chancellor Samuel von Cocceji, he reformed the judicial system and made it more efficient, and he moved the courts toward greater legal equality of all citizens by removing special courts for special social classes.[186] The reform was completed after Frederick's death, resulting in the Prussian Law Code of 1794, which balanced absolutism with human rights and corporate privilege with equality before the law. Reception to the law code was mixed as it was often viewed as contradictory.[187]

Frederick strove to put Prussia's fiscal system in order. In January 1750, Johann Philipp Graumann was appointed as Frederick's confidential adviser on finance, military affairs, and royal possessions, as well as the Director-General of all mint facilities.[188] Graumann's currency reform slightly lowered the silver content of Prussian thaler from 1⁄12 Cologne mark of silver to 1⁄14,[189] which brought the metal content of the thaler into alignment with its face value,[190] and it standardised the Prussian coinage system.[188] As a result, Prussian coins, which had been leaving the country nearly as fast as they were minted,[189] remained in circulation in Prussia.[191] In addition, Frederick estimated that he earned about one million thalers in profits on the seignorage.[189] The coin eventually became universally accepted beyond Prussia and helped increase industry and trade.[190] A gold coin, the Friedrich d'or, was also minted to oust the Dutch ducat from the Baltic trade.[192] However, the fixed ratio between gold and silver led to the gold coins being perceived as more valuable, which caused them to leave circulation in Prussia. Being unable to meet Frederick's expectations for profit, Graumann was removed in 1754.[192]

Although Frederick's debasement of the coinage to fund the Seven Years' War left the Prussian monetary system in disarray,[191] the Mint Edict of May 1763 brought it back to stability by fixing rates at which depreciated coins would be accepted and requiring tax payments in currency of prewar value. This resulted in a shortage of ready money, but Frederick controlled prices by releasing the grain stocks he held in reserve for military campaigns. Many other rulers soon followed the steps of Frederick in reforming their own currencies.[193] The functionality and stability of the reform made the Prussian monetary system the standard in Northern Germany.[194]

Around 1751 Frederick founded the Emden Company to promote trade with China. He introduced the lottery, fire insurance, and a giro discount and credit bank to stabilise the economy.[195] One of Frederick's achievements after the Seven Years' War included the control of grain prices, whereby government storehouses would enable the civilian population to survive in needy regions, where the harvest was poor.[196] He commissioned Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky to promote the trade and – to take on the competition with France – put a silk factory where soon 1,500 people found employment. Frederick followed Gotzkowsky's recommendations in the field of toll levies and import restrictions. When Gotzkowsky asked for a deferral during the Amsterdam banking crisis of 1763, Frederick took over his porcelain factory, now known as KPM.[197]

Frederick modernised the Prussian civil service and promoted religious tolerance throughout his realm to attract more settlers in East Prussia. With the help of French experts, he organised a system of indirect taxation, which provided the state with more revenue than direct taxation; though French officials administering it may have pocketed some of the profit.[198] He established new regulations for tax officials to reduce graft.[199] In 1781, Frederick made coffee a royal monopoly and employed disabled soldiers, the coffee sniffers, to spy on citizens illegally roasting coffee, much to the annoyance of the general population.[200]

Though Frederick started many reforms during his reign, his ability to see them to fulfillment was not as disciplined or thorough as his military successes.[201]

Religion

In contrast to his devoutly Calvinist father, Frederick was a religious sceptic, who has been described as a deist.[203][lower-alpha 3] Frederick was pragmatic about religious faith. Three times during his life, he presented his own confession of Christian faith: during his imprisonment after Katte's execution in 1730, after his conquest of Silesia in 1741, and just before the start of the Seven Years' War in 1756; in each case, these confessions also served personal or political goals.[206]

He tolerated all faiths in his realm, but Protestantism remained the favoured religion, and Catholics were not chosen for higher state positions.[207] Frederick wanted development throughout the country, adapted to the needs of each region. He was interested in attracting a diversity of skills to his country, whether from Jesuit teachers, Huguenot citizens, or Jewish merchants and bankers. Frederick retained Jesuits as teachers in Silesia, Warmia, and the Netze District, recognising their educational activities as an asset for the nation.[208] He continued to support them after their suppression by Pope Clement XIV.[209] He befriended the Roman Catholic Prince-Bishop of Warmia, Ignacy Krasicki, whom he asked to consecrate St. Hedwig's Cathedral in 1773.[210] He also accepted countless Protestant weavers from Bohemia, who were fleeing from the devoutly Catholic rule of Maria Theresa, granting them freedom from taxes and military service.[211] Constantly looking for new colonists to settle his lands, he encouraged immigration by repeatedly emphasising that nationality and religion were of no concern to him. This policy allowed Prussia's population to recover very quickly from its considerable losses during Frederick's three wars.[212]

Though Frederick was known to be more tolerant of Jews and Roman Catholics than many neighbouring German states, his practical-minded tolerance was not fully unprejudiced. Frederick wrote in his Testament politique:

We have too many Jews in the towns. They are needed on the Polish border because in these areas Hebrews alone perform trade. As soon as you get away from the frontier, the Jews become a disadvantage, they form cliques, they deal in contraband and get up to all manner of rascally tricks which are detrimental to Christian burghers and merchants. I have never persecuted anyone from this or any other sect; I think, however, it would be prudent to pay attention, so that their numbers do not increase.[213]

The success in integrating the Jews into areas of society where Frederick encouraged them can be seen by Gerson von Bleichröder's role during the 19th century in financing Otto von Bismarck's efforts to unite Germany.[214] Frederick was also less tolerant of Catholicism in his occupied territories. In Silesia, he disregarded canon law to install clergy who were loyal to him.[215] In Polish Prussia, he confiscated the Roman Catholic Church's goods and property,[167] making clergy dependent on the government for their pay and defining how they were to perform their duties.[216]

Like many leading figures in the Age of Enlightenment, Frederick was a Freemason,[217] having joined during a trip to Brunswick in 1738.[218] His membership legitimised the group's presence in Prussia and protected it against charges of subversion.[219] In 1786, he became the First Sovereign Grand Commander of the Supreme Council of the 33rd Degree, his double-headed eagle emblem was also used for 32nd and 33rd degree Masons following the adoption of seven additional degrees to the Masonic Rite.[220]

Frederick's religious views were sometimes criticised. His views resulted in his condemnation by the anti-revolutionary French Jesuit, Augustin Barruel. In his 1797 book, Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire du Jacobinisme (Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism), Barruel described an influential conspiracy theory that accused King Frederick of taking part in a plot which led to the outbreak of the French Revolution and having been the secret "protector and adviser" of fellow-conspirators Voltaire, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Denis Diderot, who all sought "to destroy Christianity" and foment "rebellion against Kings and Monarchs".[221]

Environment and agriculture

Frederick was keenly interested in land use, especially draining swamps and opening new farmland for colonisers who would increase the kingdom's food supply. He called it Peuplierungspolitik (peopling policy). About 1,200 new villages were founded in his reign.[222] He told Voltaire, "Whoever improves the soil, cultivates land lying waste and drains swamps, is making conquests from barbarism".[223] Using improved technology enabled him to create new farmland through a massive drainage programme in the country's Oderbruch marshland. This programme created roughly 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) of new farmland, but also eliminated vast swaths of natural habitat, destroyed the region's biodiversity, and displaced numerous native plant and animal communities. Frederick saw this project as the "taming" and "conquering" of nature,[224] considering uncultivated land "useless",[225] an attitude that reflected his enlightenment era, rationalist sensibilities.[226] He presided over the construction of canals for bringing crops to market, and introduced new crops, especially the potato and the turnip, to the country. For this, he was sometimes called Der Kartoffelkönig (the Potato King).[227]

Frederick's interest in land reclamation may have resulted from his upbringing. As a child, his father, Frederick William I, made young Frederick work in the region's provinces, teaching the boy about the area's agriculture and geography. This created an interest in cultivation and development that the boy retained when he became ruler.[228]

Frederick founded the first veterinary school in Prussia. Unusually for the time and his aristocratic background, he criticised hunting as cruel, rough and uneducated. When someone once asked Frederick why he did not wear spurs when riding his horse, he replied, "Try sticking a fork into your naked stomach, and you will soon see why."[28] He loved dogs and his horse and wanted to be buried with his greyhounds. In 1752 he wrote to his sister Wilhelmine that people indifferent to loyal animals would not be devoted to their human comrades either, and that it was better to be too sensitive than too harsh. He was also close to nature and issued decrees to protect plants.[229]

Arts and education

Frederick was a patron of music,[230] and the court musicians he supported included C. P. E. Bach, Carl Heinrich Graun and Franz Benda.[231] A meeting with Johann Sebastian Bach in 1747 in Potsdam led to Bach's writing The Musical Offering.[232] He was also a talented musician and composer in his own right, playing the transverse flute,[233] as well as composing 121 sonatas for flute and continuo, four concertos for flute and strings, four sinfonias,[234] three military marches and seven arias.[235] Additionally, the Hohenfriedberger Marsch was allegedly written by Frederick to commemorate his victory in the Battle of Hohenfriedberg during the Second Silesian War.[236] His flute sonatas were often composed in collaboration with Johann Joachim Quantz,[237] who was Frederick's occasional music tutor in his youth[238] and joined his court as composer and flute maker in 1741.[239] Frederick's flute sonatas are written in the Baroque style in which flute plays the melody, sometimes imitating operatic vocal styles like the aria and recitative, while the accompaniment was usually played by just one instrument per part to highlight the delicate sound of the flute.[240]

Frederick also wrote sketches, outlines and libretti for opera that were included as part of the repertoire for the Berlin Opera House. These works, which were often completed in collaboration with Graun,[lower-alpha 4] included the operas Coriolano (1749), Silla (1753), Montezuma (1755), and Il tempio d'Amore (1756).[242] Frederick saw opera as playing an important role in imparting enlightenment philosophy, using it to critique superstition and the Pietism that still held sway in Prussia.[243] He also attempted to broaden access to opera by making admission to it free.[244]

Frederick also wrote philosophical works,[245] publishing some of his writings under the title of The Works of a Sans-Souci Philosopher.[246] Frederick corresponded with key French Enlightenment figures, including Voltaire, who at one point declared Frederick to be a philosopher-king,[247] and the Marquis d'Argens, whom he appointed as Royal Chamberlain in 1742 and later as the Director of the Prussian Academy of Arts and Berlin State Opera.[248] His openness to philosophy had its limits. He did not admire the encyclopédistes or the French intellectual avant-garde of his time,[249] though he did shelter Rousseau from persecution for a number of years. Moreover, once he ascended the Prussian throne, he found it increasingly difficult to apply the philosophical ideas of his youth to his role as king.[250]

Like many European rulers of the time who were influenced by the prestige of Louis XIV of France and his court,[251] Frederick adopted French tastes and manners,[252] though in Frederick's case, the extent of his Francophile tendencies might also have been a reaction to the austerity of the family environment created by his father, who had a deep aversion for France and promoted an austere culture for his state.[253] He was educated by French tutors,[254] and almost all the books in his library, which covered topics as diverse as mathematics, art, politics, the classics, and literary works by 17th century French authors, were written in French.[255] French was Frederick's preferred language for speaking and writing, though he had to rely on proofreaders to correct his difficulties with its spelling.[256]

Though Frederick used German as his working language with his administration and with the army, he claimed to have never learned it properly[257] and never fully mastered speaking or writing it.[258] He also disliked the German language,[259] thinking it was inharmonious and awkward.[260] He once commented that German authors "pile parenthesis upon parenthesis, and often you find only at the end of an entire page the verb on which depends the meaning of the whole sentence".[261] He considered the German culture of his time, particularly literature and theatre, to be inferior to that of France; believing that it had been hindered by the devastation of the Thirty Years' War.[262] He suggested that it could eventually equal its rivals, but this would require a complete codification of the German language, the emergence of talented German authors and extensive patronage of the arts by Germanic rulers. This was a project he believed would take a century or more.[263] Frederick's love of French culture was not without limits either. He disapproved of the luxury and extravagance of the French royal court. He also ridiculed German princes, especially the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, Augustus III, who imitated French sumptuousness.[264] His own court remained quite Spartan, frugal and small and restricted to a limited circle of close friends,[265] a layout similar to his father's court, though Frederick and his friends were far more culturally inclined than Frederick William.[266]

Despite his distaste for the German language, Frederick did sponsor the Königliche Deutsche Gesellschaft (Royal German Society), founded in Königsberg in 1741, the aim of which was to promote and develop the German language. He allowed the association to be titled "royal" and have its seat at the Königsberg Castle, but he does not seem to have taken much interest in the work of the society. Frederick also promoted the use of German instead of Latin in the field of law, as in the legal document Project des Corporis Juris Fridericiani (Project of the Frederician Body of Laws), which was written in German with the aim of being clear and easily understandable.[267] Moreover, it was under his reign that Berlin became an important centre of German enlightenment.[268]

Architecture and the fine arts

Frederick had many famous buildings constructed in his capital, Berlin, most of which still stand today, such as the Berlin State Opera, the Royal Library (today the State Library Berlin), St. Hedwig's Cathedral, and Prince Henry's Palace (now the site of Humboldt University).[269] A number of the buildings, including the Berlin State Opera House, a wing of Schloss Charlottenburg,[270] and the renovation of Rheinsburg during Frederick's residence were built in a unique Rococo style that Frederick developed in collaboration with Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff.[271] This style became known as Frederician Rococo and is epitomised by Frederick's summer palace, Sanssouci (French for "carefree" or "without worry"),[272] which served as his primary residence and private refuge.[273]

As a great patron of the arts, Frederick was a collector of paintings and ancient sculptures; his favourite artist was Jean-Antoine Watteau. His sense of aesthetics can be seen in the picture gallery at Sanssouci, which presents architecture, painting, sculpture and the decorative arts as a unified whole. The gilded stucco decorations of the ceilings were created by Johann Michael Merck (1714–1784) and Carl Joseph Sartori (1709–1770). Both the wall panelling of the galleries and the diamond shapes of the floor consist of white and yellow marble. Paintings by different schools were displayed strictly separately: 17th-century Flemish and Dutch paintings filled the western wing and the gallery's central building, while Italian paintings from the High Renaissance and Baroque were exhibited in the eastern wing. Sculptures were arranged symmetrically or in rows in relation to the architecture.[274]

Science and the Berlin Academy

.jpg.webp)

When Frederick ascended the throne in 1740, he reinstituted the Prussian Academy of Sciences (Berlin Academy), which his father had closed down as an economy measure. Frederick's goal was to make Berlin a European cultural centre that rivalled London and Paris in the arts and sciences.[259] To accomplish this goal, he invited numerous intellectuals from across Europe to join the academy, made French the official language and made speculative philosophy the most important topic of study.[278] The membership was strong in mathematics and philosophy and included Immanuel Kant, D'Alembert, Pierre Louis de Maupertuis, and Étienne de Condillac. However the academy was in a crisis for two decades at mid-century,[268] due in part to scandals and internal rivalries such as the debates between Newtonianism and Leibnizian views, and the personality conflict between Voltaire and Maupertuis. At a higher level Maupertuis, director of the Berlin Academy from 1746 to 1759 and a monarchist, argued that the action of individuals was shaped by the character of the institution that contained them, and they worked for the glory of the state. By contrast d' Alembert took a republican rather than monarchical approach and emphasised the international Republic of Letters as the vehicle for scientific advance.[279] By 1789, the academy had gained an international repute while making major contributions to German culture and thought. For example, the mathematicians he recruited for the Berlin Academy – including Leonhard Euler, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Johann Heinrich Lambert, and Johann Castillon – made it a world-class centre for mathematical research.[280] Other intellectuals attracted to the philosopher's kingdom were Francesco Algarotti, d'Argens, and Julien Offray de La Mettrie.[278]

Military theory

Contrary to his father's fears, Frederick became a capable military commander. With the exception of his first battlefield experience at the Battle of Mollwitz, Frederick proved himself courageous in battle.[281] He frequently led his military forces personally and had a number of horses shot from under him during battle.[282] During his reign he commanded the Prussian Army at sixteen major battles and various sieges, skirmishes and other actions, ultimately obtaining almost all his political objectives. He is often admired for his tactical skills, especially for his use of the oblique order of battle,[283] an attack focused on one flank of the opposing line, allowing a local advantage even if his forces were outnumbered overall.[284] Even more important were his operational successes, especially the use of interior lines to prevent the unification of numerically superior opposing armies and defend the Prussian core territory.[285]

Napoleon Bonaparte saw the Prussian king as a military commander of the first rank;[286] after Napoleon's victory over the Fourth Coalition in 1807, he visited Frederick's tomb in Potsdam and remarked to his officers, "Gentlemen, if this man were still alive I would not be here".[287] Napoleon frequently "pored through Frederick's campaign narratives and had a statuette of him placed in his personal cabinet".[288]

Frederick's most notable military victories on the battlefield were the Battle of Hohenfriedberg, a tactical victory, fought during the War of Austrian Succession in June 1745;[289] the Battle of Rossbach, where Frederick defeated a combined Franco-Austrian army of 41,000 with only 21,000 soldiers (10,000 dead for the Franco-Austrian side with only 550 casualties for Prussia);[290] and the Battle of Leuthen, a follow-up victory to Rossbach[291] in which Frederick's 39,000 troops inflicted 22,000 casualties, including 12,000 prisoners, on Charles of Lorraine's Austrian force of 65,000.[292]

Frederick the Great believed that creating alliances was necessary, as Prussia did not have the resources of nations like France or Austria. Though his reign was regularly involved in war, he did not advocate for protracted warfare. He stated that for Prussia, wars should be short and quick: long wars would destroy the army's discipline, depopulate the country, and exhaust its resources.[293]

Frederick was an influential military theorist whose analysis emerged from his extensive personal battlefield experience and covered issues of strategy, tactics, mobility and logistics.[294] Austrian co-ruler, Emperor Joseph II wrote, "When the King of Prussia speaks on problems connected with the art of war, which he has studied intensively and on which he has read every conceivable book, then everything is taut, solid and uncommonly instructive. There are no circumlocutions, he gives factual and historical proof of the assertions he makes, for he is well versed in history."[295]

Robert Citino describes Frederick's strategic approach:

In war ... he usually saw one path to victory, and that was fixing the enemy army in place, maneuvering near or even around it to give himself a favorable position for the attack, and then smashing it with an overwhelming blow from an unexpected direction. He was the most aggressive field commander of the century, perhaps of all time, and one who constantly pushed the limits of the possible.[296]

The historian Dennis Showalter argues: "The King was also more consistently willing than any of his contemporaries to seek decision through offensive operations."[297] Yet, these offensive operations were not acts of blind aggression; Frederick considered foresight to be among the most important attributes when fighting an enemy, stating that the discriminating commander must see everything before it takes place, so nothing will be new to him.[298]

Much of the structure of the more modern German General Staff owed its existence and extensive structure to Frederick, along with the accompanying power of autonomy given to commanders in the field.[299] According to Citino, "When later generations of Prussian-German staff officers looked back to the age of Frederick, they saw a commander who repeatedly, even joyfully, risked everything on a single day's battle – his army, his kingdom, often his very life."[296] As far as Frederick was concerned, there were two major battlefield considerations – speed of march and speed of fire.[300] So confident in the performance of men he selected for command when compared to those of his enemy, Frederick once quipped that a general considered audacious in another country would be ordinary in Prussia because Prussian generals will dare and undertake anything that is possible for men to execute.[301]

After the Seven Years' War, the Prussian military acquired a formidable reputation across Europe.[302] Esteemed for their efficiency and success in battle, the Prussian army of Frederick became a model emulated by other European powers, most notably by Russia and France.[303] To this day, Frederick continues to be held in high regard as a military theorist and has been described as representing the embodiment of the art of war.[304]

Later years and death

Near the end of his life, Frederick grew increasingly solitary. His circle of close friends at Sanssouci gradually died off with few replacements, and Frederick became increasingly critical and arbitrary, to the frustration of the civil service and officer corps. Frederick was immensely popular among the Prussian people because of his enlightened reforms and military glory; the citizens of Berlin always cheered him when he returned from administrative or military reviews. Over time, he was nicknamed Der Alte Fritz (The Old Fritz) by the Prussian people, and this name became part of his legacy.[305] Frederick derived little pleasure from his popularity with the common people, preferring instead the company of his pet Italian greyhounds,[306] whom he referred to as his "marquises de Pompadour" as a jibe at the French royal mistress.[307] Even in his late 60s and early 70s when he was increasingly crippled by asthma, gout and other ailments, he rose before dawn, drank six to eight cups of coffee a day, "laced with mustard and peppercorns", and attended to state business with characteristic tenacity.[308]

On the morning of 17 August 1786, Frederick died in an armchair in his study at Sanssouci, aged 74. He left instructions that he should be buried next to his greyhounds on the vineyard terrace, on the side of the corps de logis of Sanssouci. His nephew and successor Frederick William II instead ordered Frederick's body to be entombed next to his father, Frederick William I, in the Potsdam Garrison Church. Near the end of World War II, German dictator Adolf Hitler ordered Frederick's coffin to be hidden in a salt mine to protect it from destruction. The United States Army relocated the remains to Marburg in 1946; in 1953, the coffins of Frederick and his father were moved to Burg Hohenzollern.[309]

On the 205th anniversary of his death, on 17 August 1991, Frederick's coffin lay in state in the court of honour at Sanssouci, covered by a Prussian flag and escorted by a Bundeswehr guard of honour. After nightfall, Frederick's body was interred in the terrace of the vineyard of Sanssouci—in the still existing crypt he had built there—without pomp, in accordance with his will.[310][lower-alpha 6] Visitors to his grave often place potatoes on the gravestone in honour of his role in promoting the use of the potato in Prussia.[312]

Historiography and legacy

Frederick's legacy has been subject to a wide variety of interpretations.[313] For instance, Thomas Carlyle's History of Frederick the Great (8 vol. 1858–1865) emphasised the power of one great "hero", in this case Frederick, to shape history.[314] In German memory, Frederick became a great national icon and many Germans said he was the greatest monarch in modern history. These claims particularly were popular in the 19th century.[315] For example, German historians often made him the romantic model of a glorified warrior, praising his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to duty and success in building up Prussia to a leading role in Europe.[316] Frederick's popularity as a heroic figure remained high in Germany even after World War I.[317]

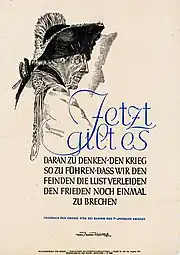

Between 1933 and 1945, the Nazis glorified Frederick as a precursor to Adolf Hitler and presented Frederick as holding out hope that another miracle would again save Germany at the last moment.[318] In an attempt to legitimise the Nazi regime, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels commissioned artists to render fanciful images of Frederick, Bismarck, and Hitler together in order to create a sense of a historical continuum amongst them.[319] Throughout World War II, Hitler often compared himself to Frederick the Great,[320] and he kept a copy of Anton Graff's portrait of Frederick with him to the end in the Führerbunker in Berlin.[321]

After the defeat of Germany after 1945, the role of Prussia in German history was minimised. Compared to the pre-1945 period, Frederick's reputation was downgraded in both East[322] and West Germany,[323] partly due to the Nazis' fascination with him and his supposed connection with Prussian militarism.[324] During the second half of the 20th century, political attitudes towards Frederick's image were ambivalent, particularly in communist East Germany.[325] For example, immediately after World War II images of Prussia were removed from public spaces,[326] including Frederick's equestrian statue on the Unter den Linden, but in 1980 his statue was once more re-erected on its original location.[327] Since the end of the Cold War, Frederick's reputation has continued to grow in the now reunified Germany.[328]

In the 21st century, the view of Frederick as a capable and effective leader also remains strong among military historians.[329] However, the originality of his achievements remains a topic of debate,[330] as many were based on developments already under way.[331] He has also been studied as a model of servant leadership in management research[332] and is held in high regard for his patronage of the arts.[333] He has been seen as an exemplar of enlightened absolutism,[334] though this label has been questioned in the 21st century as many enlightenment principles directly contrast with his military reputation.[335]

Works by Frederick the Great

Selected works in English

- Anti-Machiavel: The Refutation of Machiavelli s Prince. Translated by Sonnino, Paul. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. 1980 [1740]. ISBN 9780821405598.

- The History of My Own Times. Posthumous Works of Frederic II. King of Prussia. Vol. 1. Translated by Holcroft, Thomas. London: G. G. J. & J. Robinson. 1789 [1746].

- The History of the Seven Years War, Part I. Posthumous Works of Frederic II. King of Prussia. Vol. 2. Translated by Holcroft, Thomas. London: G. G. J. & J. Robinson. 1789 [1788].

- The History of the Seven Years War, Part II. Posthumous Works of Frederic II. King of Prussia. Vol. 3. Translated by Holcroft, Thomas. London: G. G. J. & J. Robinson. 1789 [1788].

- Memoirs from the Peace of Hubertsburg to the Partition of Poland. Posthumous Works of Frederic II. King of Prussia. Vol. 4. Translated by Holcroft, Thomas. London: G. G. J. & J. Robinson. 1789 [1788].

- Military Instructions from the King of Prussia to His Generals. Translated by Foster, T. London: J. Cruttwell. 1818 [1747].

- Memoirs of the House of Brandenburg to Which are Added Four Dissertations. London: J. Nourse. 1758 [1750].

Collections

- Preuss, J. D. E., ed. (1846–1857). Œuvres de Frédéric Le Grand [Works of Frederick the Great] (in French). (31 vols.)

- Droysen, Johann Gustav, ed. (1879–1939). Politische Correspondenz Friedrich's des Großen [Political Correspondence of Frederick the Great] (in German). (46 vols.)

Editions of music

- Spitta, Philipp, ed. (1889). Musikalische Werke: Friedrichs des Grossen [Musical works: Frederick the Great] (in German). Vol. i–iii. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. OCLC 257496423.

- Lensewski, Gustav, ed. (1925). Friedrich der Grosse: Kompositionen [Friedrich the Great: Compositions] (in German). Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

See also

References

Informational notes

- ↑ According to the French diplomat Louis Guy Henri de Valori, when he asked Frederick why he allowed the Saxon and Austrian forces to cross the mountains unopposed in the first place, Frederick answered: "mon ami, quand on veut prendre des souris, il faut tenir la souricière ouverte, ils entreront et je les battrai." ("My friend, when you want to catch mice, you have to keep the mousetrap open, they will enter and I will batter them.")[85]

- ↑ In the second printing of the Anti-Machiavel, Voltaire changed premier domestique (first servant) to premier Magistrat (first magistrate). Compare Frederick's words from the handwritten manuscript[180] to Voltaire's edited 1740 version.[181]

- ↑ He remained critical of Christianity.[204] See Frederick's De la Superstition et de la Religion (Superstition and Religion) in which he says in the context of Christianity in Brandenburg: "It is a shame to human understanding, that at the beginning of so learned an age as the XVIIIth [18th century] all manner of superstitions were yet subsisting."[205]

- ↑ Frederick's relationship to Graun is illustrated by his comment upon hearing news of Graun's death in Berlin, which he received eight days after the Battle of Prague: "Eight days ago, I lost my best field-marshal (Schwerin), and now my Graun. I shall create no more field-marshals or conductors until I can find another Schwerin and another Graun."[241]

- ↑ George Keith and his brother James Francis Edward Keith were Scottish soldiers in exile who joined Frederick's entourage after 1745.[275] They are unrelated to the Keith brothers, Peter and Robert, who were Frederick's companions when he was Crown Prince.[276]

- ↑ In his 1769 will, Frederick wrote "I have lived as a philosopher and wish to be buried as such, without pomp or parade...Let me be deposited in the vault which I had constructed for myself, on the upper terrace of San Souci."[311]

- ↑ Translation: "Now we have to think of leading the war in a way that we spoil the desire of the enemies to break the peace once again."

Citations

- ↑ Schieder 1983, p. 1.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Gooch 1947, p. 217.

- ↑ Schieder 1983, p. 39.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 14–15; MacDonogh 2000, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, pp. 12–13; Ritter 1936, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 3 Lavisse 1892, pp. 128–220.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 54–55; Mitford 1970, pp. 28–29; Schieder 1983, p. 7.

- ↑ Christian 1888, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 47; Mitford 1970, p. 19; Showalter 1986, p. xiv.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 39–38; MacDonogh 2000, p. 47; Ritter 1936, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 37.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, p. 58; MacDonogh 2000, p. 35; Ritter 1936, p. 54.

- ↑ Wilhelmine 1888, p. 83.

- ↑ Alings 2022; Blanning 2015, 32:50–34:00; Blanning 2016, p. 193; Johansson 2016, pp. 428–429; Krysmanski 2022, pp. 24–30.

- ↑ Ashton 2019, p. 113.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 42–43; MacDonogh 2000, p. 49.

- ↑ Berridge 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, pp. 29–31; Schieder 1983, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Mitford 1970, pp. 21–24; Reiners 1960, p. 31.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 28; Fraser 2001, p. 25; Kugler 1840, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 51–53; Blanning 2015, 3:55–4:56; Simon 1963, p. 76; Mitford 1970, p. 61.

- ↑ de Catt 1884, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, p. 41.

- 1 2 Mitford 1970, p. 61.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, p. 52.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, p. 94.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 88–89; MacDonogh 2000, pp. 86–89.

- ↑ Reddaway 1904, p. 44.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, p. 63.

- ↑ Crompton 2003, p. 508.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 88; Mitford 1970, p. 71.

- ↑ Reddaway 1904, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 119–122.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, p. 69.

- ↑ Locke 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, p. 96.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 108–113.

- ↑ Reiners 1960, p. 71.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, p. 122.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, p. 123.

- ↑ Hamilton 1880, p. 316.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 125.

- ↑ Duffy 1985, p. 20.

- ↑ Ergang 1941, p. 38.

- ↑ Sontheimer 2016, pp. 106–107: Bei der Thronbesteigung von Friedrich II. kam in Preußen auf 28 Bewohner ein Soldat, in Großbritannien auf 310. Da Preußen nur 2,24 Millionen Bewohner hatte, war die Armee mit 80000 Mann noch relativ klein, verschlang aber 86 Prozent des Staatshaushalts. [Upon Frederick II's accession to the throne Prussia had one soldier for every 28 inhabitants, Great Britain for every 310. Since Prussia had only 2.24 million residents the army was still relatively small with 80,000 men, but devoured 86% of the state budget.]

- ↑ Baron 2015.

- ↑ Billows 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ Longman 1899, p. 19.

- 1 2 Luvaas 1966, p. 3.

- ↑ Crompton 2003, p. 510.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, pp. 544–545.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 141.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 154.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2000, p. 152; Schieder 1983, p. 96; Weeds 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Clark 2006, pp. 192–193; Duffy 1985, pp. 22–23; Kugler 1840, p. 160.

- ↑ Clark 2006, pp. 192–193; Duffy 1985, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Clark 2006, p. 192.

- ↑ Kulak 2015, p. 64.

- ↑ Clark 2006, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 196–203.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 203.

- 1 2 Luvaas 1966, p. 4.

- ↑ Luvaas 1966, p. 46.

- ↑ Luvaas 1966, p. 4; Ritter 1936, p. 84.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 220.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 228.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 236; Mitford 1970, p. 110.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, p. 124; Kugler 1840, p. 195.

- ↑ Duffy 1985, pp. 44, 49; Fraser 2001, p. 126.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 258; Luvaas 1966, p. 4.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, p. 121; Kugler 1840, p. 196.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 279.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 290–293; Duffy 1985, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Fraser 2001, p. 165.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 294–297; Duffy 1985, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, p. 285.

- ↑ Duffy 1985, p. 58.

- ↑ Kugler 1840, p. 217.

- ↑ Valori 1820, p. 226.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 321–324; Duffy 1985, pp. 60–65; Fraser 2001, pp. 178–183.

- ↑ Asprey 1986, pp. 334–338; Duffy 1985, pp. 68–69; Showalter 2012, pp. 120–123.