Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, VC, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCIE, VD, PC, FRSGS (30 September 1832 – 14 November 1914) was a British Victorian era general who became one of the most successful British military commanders of his time. Born in India to an Anglo-Irish family, Roberts joined the East India Company Army and served as a young officer in the Indian Rebellion during which he was awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry. He was then transferred to the British Army and fought in the Expedition to Abyssinia and the Second Anglo-Afghan War, in which his exploits earned him widespread fame. Roberts would go on to serve as the Commander-in-Chief, India before leading British Forces for a year during the Second Boer War. He also became the last Commander-in-Chief of the Forces before the post was abolished in 1904.

A man of small stature, Roberts was affectionately known to his troops and the wider British public as "Bobs" and revered as one of Britain's leading military figures at a time when the British Empire reached the height of its power.[1] He became a symbol for the British Army and in later life became an influential proponent of stronger defence in response to the increasing threat that the German Empire posed to Britain in the lead up to the First World War.[2]

Early life

Born at Cawnpore, India, on 30 September 1832, Roberts was the son of General Sir Abraham Roberts,[3] who had been born into an Anglo-Irish family in County Waterford in the south-east of Ireland.[3] At the time, Sir Abraham was commanding the 1st Bengal European Regiment.[4] Roberts was named Sleigh in honour of the garrison commander, Major General William Sleigh.[3] His mother was Edinburgh-born Isabella Bunbury,[3] daughter of Major Abraham Bunbury from Kilfeacle in County Tipperary.[5]

Roberts was educated at Eton,[3] Sandhurst,[3] and Addiscombe Military Seminary[3] before entering the East India Company Army as a second lieutenant with the Bengal Artillery on 12 December 1851.[3] He became Aide-de-Camp to his father in 1852, transferred to the Bengal Horse Artillery in 1854 and was promoted to lieutenant on 31 May 1857.[6]

Indian Rebellion of 1857

Roberts fought in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, seeing action during the siege and capture of Delhi where he was slightly wounded, and found a dying John Nicholson amidst the chaos of the battle.[7] He was then present at the relief of Lucknow where, as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General, he was attached to the staff of Sir Colin Campbell, Commander-in-Chief, India.[3] He was awarded the Victoria Cross for actions on 2 January 1858 at Khudaganj.[3] The citation reads:

Lieutenant Roberts' gallantry has on every occasion been most marked.

On following the retreating enemy on 2 January 1858, at Khodagunge, he saw in the distance two Sepoys going away with a standard. Lieutenant Roberts put spurs to his horse, and overtook them just as they were about to enter a village. They immediately turned round, and presented their muskets at him, and one of the men pulled the trigger, but fortunately the caps snapped, and the standard-bearer was cut down by this gallant young officer, and the standard taken possession of by him. He also, on the same day, cut down another Sepoy who was standing at bay, with musket and bayonet, keeping off a Sowar. Lieutenant Roberts rode to the assistance of the horseman, and, rushing at the Sepoy, with one blow of his sword cut him across the face, killing him on the spot.[8]

He was also mentioned in despatches for his service at Lucknow in March 1858.[9] In common with other officers, he transferred from the East India Company Army to the Indian Army that year.[6]

Abyssinia and Afghanistan

Having been promoted to second captain on 12 November 1860[10] and to brevet major on 13 November 1860,[11] Roberts transferred to the British Army in 1861 and served in the Umbeyla and Abyssinian campaigns of 1863 and 1867–1868 respectively.[3] Having been promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel on 15 August 1868[12] and to the substantive rank of captain on 18 November 1868,[13] Roberts also fought in the Lushai campaign of 1871–1872.[3]

He was promoted to the substantive rank of major on 5 July 1872,[14] appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) on 10 September 1872[15] and promoted to brevet colonel on 30 January 1875.[16] That year he became Quartermaster-General of the Bengal Army.[12]

He was given command of the Kurram Valley Field Force in October 1878 and took part in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[17] For his success at the Battle of Peiwar Kotal in December 1878, he received the thanks of Parliament, was promoted to the substantive rank of major general on 31 December 1878[18] and was advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) on 25 July 1879.[19]

The Treaty of Gandamak of May 1879 brought peace with Afghanistan. However, after the murder of Sir Louis Cavagnari, the British envoy in Kabul, in September 1879, the second phase of the war began.[12] Roberts was put in command of the Kabul Field Force and despatched to Kabul to seek retribution. After victory at the Battle of Charasiab on 6 October 1879, Roberts occupied Kabul,[3] and was given the local rank of lieutenant-general on 11 November 1879.[20] In December 1879, Roberts' force was besieged in the Sherpur Cantonment outside Kabul until, on 23 December, he repulsed a mass attack and reoccupied the city.[3] In May 1880, Lieutenant General Sir Donald Stewart arrived in Kabul from Kandahar with a further 7,200 troops, taking over the Kabul command from Roberts.[21]

After the defeat of a British brigade at Maiwand near Kandahar on 27 July 1880, Roberts was appointed commander of the Kabul and Kandahar Field Force. He led his 10,000 troops across 300 miles of rough terrain to relieve Kandahar and defeat Ayub Khan at the Battle of Kandahar on 1 September 1880.[3] For his services, Roberts again received the thanks of Parliament, and was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) on 21 September 1880[22] and appointed Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) during 1880.[23]

After a very brief interval as Governor of Natal and Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Transvaal Province and High Commissioner for South Eastern Africa with effect from 7 March 1881,[24] Roberts (having become a baronet on 11 June 1881)[25] was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army on 16 November 1881.[26] Promoted to the substantive rank of lieutenant general on 26 July 1883,[27] he became Commander-in-Chief, India on 28 November 1885[28] and was advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE) on 15 February 1887[29] and to Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE) on reorganisation of the Order on 21 June 1887.[30] This was followed by his promotion to a supernumerary general on 28 November 1890[31] and to the substantive rank of general on 31 December 1891.[32] On 23 February 1892 he was created Baron Roberts, of Kandahar in Afghanistan and of the City of Waterford.[33]

Ireland

After relinquishing his Indian command and becoming Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) on 3 June 1893,[34] Roberts was relocated to Ireland as Commander-in-Chief of British forces there from 1 October 1895.[35] He was promoted field marshal on 25 May 1895[36] and created a knight of the Order of St Patrick in 1897.[37]

While in Ireland, Roberts completed a memoir of his years in India, which was published in 1897 as Forty-one Years in India: from Subaltern to Commander-in-chief.[38]

Second Anglo-Boer War

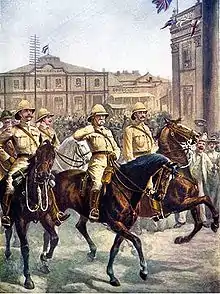

On 23 December 1899 Roberts left England to return to South Africa with his chief of staff Lord Kitchener on the RMS Dunottar Castle to take overall command of British forces in the Second Boer War, subordinating the previous commander, General Redvers Buller. He arrived in Cape Town on 10 January 1900.[39] His appointment was a response to a string of defeats in the early weeks of the war and was accompanied by the despatch of huge reinforcements.[40] For his headquarters staff, he appointed military men from far and wide: Kitchener (Chief of Staff) from the Sudan, Frederick Burnham (Chief of Scouts), the American scout, from the Klondike, George Henderson from the Staff College, Neville Chamberlain from Afghanistan and William Nicholson (Military Secretary) from Calcutta.[41] Roberts launched a two-pronged offensive, personally leading the advance across the open veldt into the Orange Free State, while Buller sought to eject the Boers from the hills of Natal – during which Lord Roberts's son was killed, earning a posthumous V.C.[42]

Having raised the Siege of Kimberley, at the Battle of Paardeberg on 27 February 1900 Roberts forced the Boer General Piet Cronjé to surrender with some 4,000 men.[43] After another victory at Poplar Grove, Roberts captured the Free State capital Bloemfontein on 13 March. His further advance was delayed by his disastrous attempt to reorganise his army's logistic system on the Indian Army model in the midst of the war. The resulting chaos and shortage of supplies contributed to a severe typhoid epidemic that inflicted far heavier losses on the British forces than they suffered in combat.[44]

On 3 May, Roberts resumed his offensive towards the Transvaal, capturing its capital Pretoria on 31 May. Having defeated the Boers at Diamond Hill and linked up with Buller, he won the last victory of his career at Bergendal on 27 August.[45]

Strategies devised by Roberts, to force the Boer commandos to submit, included concentration camps and the burning of farms. Conditions in the concentration camps, which had been conceived by Roberts as a form of control of the families whose farms he had destroyed, began to degenerate rapidly as the large influx of Boers outstripped the ability of the small British force to cope. The camps lacked space, food, sanitation, medicine, and medical care, leading to rampant disease and a very high death rate for those Boers who entered. By the war's end, 26,370 women and children (81% were children) had died in the concentration camps.[46] For a brief period in 1900, Roberts also authorised the army's use of civilian hostages for the protection of trains from Boer guerrilla units.[47]

With the Boer republics' main towns occupied, and the war apparently effectively over, on 12 December 1900 Roberts handed over command to Lord Kitchener.[48] Roberts returned to England to receive yet more honours: he was made a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter[49] and also created Earl Roberts, of Kandahar in Afghanistan and Pretoria in the Transvaal Colony and of the City of Waterford, and Viscount St Pierre.[50]

He became a Knight of Grace of the Order of St John on 11 March 1901[51] and then a Knight of Justice of that order on 3 July 1901.[52] He was also awarded the German Order of the Black Eagle during the Kaiser's visit to the United Kingdom in February 1901.[53][54] He was among the original recipients of the Order of Merit in the 1902 Coronation Honours list published on 26 June 1902,[55] and received the order from King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace on 8 August 1902.[56][57]

Later life

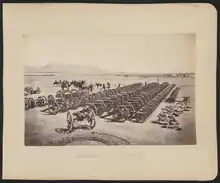

Lord Roberts became the last Commander-in-Chief of the Forces on 3 January 1901.[58] During his time in office he introduced the Short Magazine Lee Enfield Rifle and the 18-pounder Gun and provided improved education and training for soldiers.[59] In September 1902, Lord Roberts and St John Brodrick, Secretary of State for War, visited Germany to attend the German army manoeuvres as guest of the Emperor Wilhelm.[60] He served as Commander-in-Chief for three years before the post was abolished as recommended by Lord Esher in the Esher Report in February 1904.[3]

He was the initial president of the Pilgrims Society during 1902.[61]

National Service League

Following his return from the Boer War, he was instrumental in promoting the mass training of civilians in rifle shooting skills through membership of shooting clubs, and a facsimile of his signature appears to this day on all official targets of the National Smallbore Rifle Association.[62]

In retirement he was a keen advocate of introducing compulsory military training in Britain, to prepare for a great European war. He campaigned for this as president of the National Service League, holding the post from 1905 until 1914.[3] In 1907 a selection of his speeches was published under the title A Nation in Arms. Roberts provided William Le Queux with information for his novel The Invasion of 1910 and checked the proofs.[63] In 1910 Roberts' friend Ian Hamilton, in co-operation with the Secretary of State for War, Richard Haldane, published Compulsory Service in which he attacked Roberts' advocacy of compulsory military training. This caused much hurt to Roberts. He replied, with the help of Leo Amery and J. A. Cramb, with Fallacies and Facts (1911).[64]

In a speech in Manchester's Free Trade Hall on 22 October 1912 Roberts pointed out that Cobden and Bright's prediction that peace and universal disarmament would follow the adoption of free trade had not happened. He further warned of the threat posed by Germany:

In the year 1912, just as in 1866 and just as in 1870, war will take place the instant the German forces by land and sea are, by their superiority at every point, as certain of victory as anything in human calculation can be made certain...We may stand still. Germany always advances and the direction of her advance, the line along which she is moving, is now most manifest. It is towards...complete supremacy by land and sea.[65]

He claimed that Germany was making enormous efforts to prepare for war and ended his speech by saying:

Gentlemen, only the other day I completed my eightieth year...and the words I am speaking to-day are, therefore, old words—the result of years of earnest thought and practical experience. But, Gentlemen, my fellow-citizens and fellow-Britishers, citizens of this great and sacred trust, this Empire, if these were my last words, I still should say to you—"arm yourselves" and if I put to myself the question, How can I, even at this late and solemn hour, best help England,—England that to me has been so much, England that for me has done so much—again I say, "Arm and prepare to acquit yourselves like men, for the day of your ordeal is at hand".[66]

The historian A. J. A. Morris claimed that this speech caused a sensation due to Roberts' warnings about Germany.[67] It was much criticised by the Liberal and Radical press. The Manchester Guardian condemned the

insinuation that the German Government's views of international policy are less scrupulous and more cynical than those of other Governments...Prussia's character among nations is, in fact, not very different from the character which Lancashire men give to themselves as compared with other Englishmen. It is blunt, straightforward, and unsentimental.[68]

The Nation claimed Roberts had an "unimaginative soldier's brain" and that Germany was "a friendly Power" who since 1870 "has remained the most peaceful and the most self-contained, though doubtless not the most sympathetic, member of the European family".[69] The historian John Terraine, writing in 1993, said: "At this distance of time the verdict upon Lord Robert's Manchester speech must be that, in speaking out clearly on the probability of war, he was doing a patriotic service comparable to Churchill's during the Thirties".[70]

Kandahar ski race

Roberts became vice-president of the Public Schools Alpine Sports Club during 1903.[71] Eight years later on 11 January 1911, the Roberts of Kandahar Challenge Cup (so named because Roberts donated the trophy cup) was organised at Crans-Montana (Crans-sur-Sierre) by winter sports pioneer Arnold Lunn.[72] An important part of the history of skiing, the races was a forerunner of the downhill ski race.[73] The Kandahar Ski Club, founded by Lunn, was named after the Cup and subsequently lent its name to the Arlberg-Kandahar ski race. The name Kandahar is still used for the premier races of the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup circuit.[74]

He took part in the funeral processions following the deaths of Queen Victoria in January 1901[75] and King Edward VII in May 1910.[76]

Curragh incident

Roberts was approached for advice about the Ulster Volunteer Force, formed in January 1913 by Ulstermen who had no wish to be part of a Home Rule Ireland. Too old himself to take active command, Roberts recommended Lieutenant General Sir George Richardson, formerly of the Indian Army, as commander.[77]

On the morning of 20 March – the morning of Paget's speech which provoked the Curragh incident, in which Hubert Gough and other officers threatened to resign rather than coerce Ulster – Roberts, aided by Wilson, drafted a letter to the Prime Minister, urging him not to cause a split in the army.[78]

Roberts had asked the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) John French to come and see him at Ascot on 19 March; French had been too busy but invited Roberts to visit him when next in London. On the morning of 21 March Roberts and French had an acrimonious telephone conversation in which Roberts told French that he would share the blame if he collaborated with the Cabinet's "dastardly" attempt to coerce Ulster, and then, after French told him that he would "do his duty as a soldier" and obey lawful orders, put the phone down on him. Soon after, Roberts received a telegram from Hubert Gough, purporting to ask for advice, although possibly designed to goad him into further action. Roberts requested an audience with King George V, who told him that Seely (Secretary of State for War), to whom the King had recently spoken, had complained that Roberts was "at the bottom" of the matter, had incited Gough, and had called the politicians "swine and robbers" in his phone conversation with French. Roberts indignantly denied this, claiming that he had not been in contact with Gough for "years" and that he had advised officers not to resign.[79] Roberts's claim may not be the whole truth as Gough was on first name terms with Roberts's daughter and later gave her copies of key documents relating to the Incident.[80]

Roberts also had an interview with Seely (he was unable to locate French, who was in fact himself having an audience with the King at the time) but came away thinking him "drunk with power", although he learned that Paget had been acting without authority (in talking of "commencing active operations" against Ulster and in offering officers a chance to discuss hypothetical orders and to threaten to resign) and left a note for Hubert Gough to this effect. This note influenced the Gough brothers in being willing to remain in the Army, albeit with a written guarantee that the Army would not have to act against Ulster. After Roberts's lobbying, the King insisted that Asquith make no further troop movements in Ulster without consulting him.[79]

Roberts wrote to French (22 March) denying the "swine and robbers" comment, although French's reply stressed his hurt that Roberts had thought so ill of him.[82]

Death

Roberts died of pneumonia at St Omer, France, on 14 November 1914 while visiting Indian troops fighting in the First World War.[3] His body was taken to Ascot by special train for a funeral service on 18 November before being taken to London.[83] After lying in state in Westminster Hall (one of only two people who were not members of the royal family to do so during the 20th century, the other being Sir Winston Churchill), he was given a state funeral and was then buried in St. Paul's Cathedral.[3]

Roberts had lived at Englemere House at Ascot in Berkshire. His estate was probated during 1915 at £77,304[3] (equivalent to £7.89 million as of 2022).[84]

Honours

On 28 February 1908 he was awarded the Volunteer Officers' Decoration in recognition of his honorary service in the Volunteer Force.[85]

His long list of honorary military posts included: honorary colonel of the 2nd London Corps from 24 September 1887,[86] honorary colonel of the 5th Battalion, the Sherwood Foresters (Derbyshire Regiment) from 29 December 1888,[87] honorary colonel of the 1st Newcastle upon Tyne (Western Division), Royal Artillery from 18 April 1894,[88] honorary colonel of the Waterford Artillery (Southern Division) from 4 March 1896,[89] colonel-commandant of the Royal Artillery from 7 October 1896,[90] honorary colonel of the 3rd Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment from 1 January 1898,[91] honorary colonel of the City of London Imperial Volunteers from 10 March 1900,[92] honorary colonel of the 3rd Volunteer Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment from 5 September 1900,[93] colonel of the Irish Guards from 17 October 1900,[94] honorary colonel of the 2nd Hampshire (Southern Division), Royal Garrison Artillery from 15 August 1901,[95] honorary colonel of the 3rd (Dundee Highland) Volunteer Battalion, the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) from 19 September 1903,[96] honorary colonel of the North Somerset Yeomanry from 1 April 1908,[97] honorary colonel of the 6th Battalion, the City of London (Rifles') Regiment from 1 April 1908,[98] honorary colonel of the 1st Wessex Brigade from 1 April 1908,[99] honorary colonel of 6th Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment from 1 April 1908,[100] honorary colonel of The Waterford Royal Field Reserve Artillery from 2 August 1908[101] and honorary colonel of 1st (Hull) Battalion, The East Yorkshire Regiment from 11 November 1914 (three days before his death).[102] Additionally he was Colonel of the National Reserve from 5 August 1911.[103]

Lord Roberts received civic honours from a number of universities, cities and livery companies, including:

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Cardiff – 26 January 1894[104]

- Honorary Freedom of the borough of Portsmouth – 1898 (and received a Sword of Honour from the town in 1902)[105]

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Canterbury – 26 August 1902[106]

- Honorary Freedom of the borough of Dover – 28 August 1902[107]

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Bath – 26 September 1902[108]

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Winchester – 9 October 1902[109]

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Liverpool – 11 October 1902[110]

- Honorary Freedom of the borough of Croydon – 14 October 1902[111]

- Honorary Freedom of the borough of Bournemouth – 22 October 1902[112]

- Honorary Freeman, Worshipful Company of Fishmongers[113]

- Honorary Freedom and livery of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths – 6 November 1902 – "in recognition of his distinguished services to the country".[114]

In 1893 he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (FRSGS).[115]

Family

Roberts married Nora Henrietta Bews, the daughter of Captain John Bews on 17 May 1859. The couple had the following six children of whom three, a son and two daughters, survived infancy:[3]

- Nora Frederica Roberts. Born 10 March 1860, died 3 March 1861

- Eveleen Sautelle Roberts. Born 18 July 1868, died 8 February 1869.

- Frederick Henry Roberts. Born August 1869, died August 1869.

- Aileen Mary Roberts. Born 20 September 1870, died 9 October 1944.

- Frederick Hugh Sherston Roberts. Born 8 January 1872, died 17 December 1899.

- Ada Edwina Stewart Roberts. Born 28 March 1875, died 21 February 1955.

Roberts' son, The Hon. Frederick Roberts, VC, was killed in action on 17 December 1899 at the Battle of Colenso during the Boer War. Roberts and his son were one of only three pairs of fathers and sons to be awarded the VC. Today, their Victoria Crosses are in the National Army Museum. His barony became extinct, but, by the special remainder granted with them, he was succeeded in the earldom and viscountcy by his elder surviving daughter, Aileen.[116] She was succeeded by her younger sister, Ada Edwina.[3]

Publications

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Forty-One Years in India: from Subaltern to Commander-in-chief (1897, reprinted Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 2005)

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Lord Roberts' Message to the Nation (1912, John Murray, London)

Legacy

In March 1898, a statue of Lord Roberts, sculpted by Harry Bates, was unveiled on the Maidan in Calcutta.[117] The statue of Roberts on horseback sits on a pedestal with reliefs on each side depicting Sikh, Highlander and Gurkha cavalry and infantry, and statues of Britannia/Victory and India/Fortitude in front and behind. After the statue was commissioned Roberts started sitting for the sculptor in 1894 and a bust was displayed at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1896.[117]

After Roberts' death in 1914, money was raised to place a copy of the Calcutta statue as a memorial in Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow.[117][118] Almost identical to the original statue, the memorial in Glasgow only includes minor changes like the inclusion of a quote from a speech Roberts gave in Glasgow in 1913 to promote national service.[117] "I seem to see the gleam in the near distance of the weapons and accoutrements of this Army of the future, this Citizen Army, the wonder of these islands, and the pledge of peace and of the continued greatness of this Empire." The memorial was unveiled by his widow.[119]

A second copy of the statue was erected on Horse Guards Parade in London and unveiled in 1924.[117][120] It is smaller and simpler than the other two, and sits on a simpler pedestal without the reliefs or extra figures. After Indian independence from the British Empire, the Roberts statue in Calcutta was moved with other statues to Barrackpore in the 1970s, and then by itself to the Artillery Centre, Nashik Road.[117]

Roberts Barracks at Larkhill Garrison[121] and the town of Robertsganj in Uttar Pradesh are named after him.[122]

Lord Roberts French Immersion Public School in London, Ontario,[123] Lord Roberts Junior Public School in Scarborough, Ontario,[124] and Lord Roberts Elementary Schools in Vancouver, British Columbia,[125] and Winnipeg, Manitoba are named after him.[126] Roberts is also a Senior Boys house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School.[127]

The Lord Roberts Centre – a facility at the National Shooting Centre built for the 2002 Commonwealth Games, and HQ of the National Smallbore Rifle Association (which Roberts was fundamental in founding) is named in his honour.[128]

On 29 May 1900, Pretoria surrendered to the British commander-in-chief, Lord Roberts.[129] Due to the prevalence of malaria and because the area had become too small, he relocated his headquarters from the vicinity of the Normal College to a high-lying site 10 km south-west of the city – hence the name Roberts Heights.[129] Roberts Heights, a busy military town, the largest in South Africa and resembling Aldershot, soon developed. On 15 December 1938, the name was changed to Voortrekkerhoogte[129] and again to Thaba Tshwane on 19 May 1998.[130]

On a visit to the Victoria Falls, one of the larger islands just upstream of the Falls was named Kandahar Island in his honour.[131]

The grave of Roberts' charger Vonolel (named after a Lushai King whose descendants Roberts had fought in 1871) is marked by a headstone in the gardens of The Royal Hospital Kilmainham, in Dublin.[132]

Notes

- ↑ "Poems - 'Bobs'". Kiplingsociety.co.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "16 November 1914 - The late Lord Roberts. - Trove". Trove.nla.gov.au. 16 November 1914. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Robson, Brian (2008). "Roberts, Frederick Sleigh, first Earl Roberts (1832–1914)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35768. Retrieved 25 February 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "ny times". The New York Times. 16 January 1897. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Bunbury of Kilfeacle Family History". Turtlebunbury.com. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- 1 2 Heathcote, p. 246.

- ↑ "No. 22095". The London Gazette. 10 February 1858. p. 673.

- ↑ "No. 22212". The London Gazette. 24 December 1858. p. 5516.

- ↑ "No. 22143". The London Gazette. 25 May 1858. p. 2589.

- ↑ "No. 22621". The London Gazette. 29 April 1862. p. 2232.

- ↑ "No. 22480". The London Gazette. 15 February 1861. p. 655.

- 1 2 3 Heathcote, p. 247.

- ↑ "No. 23442". The London Gazette. 17 November 1868. p. 5924.

- ↑ "No. 23876". The London Gazette. 16 July 1872. p. 3193.

- ↑ "No. 23895". The London Gazette. 10 September 1872. p. 3969.

- ↑ "No. 24188". The London Gazette. 9 March 1875. p. 1528.

- ↑ Roberts 1896, p. 348.

- ↑ "No. 24668". The London Gazette. 14 January 1879. p. 174.

- ↑ "No. 24747". The London Gazette. 29 July 1879. p. 4697.

- ↑ "No. 24837". The London Gazette. 23 April 1880. p. 2658.

- ↑ Vetch, R.H. "Sir Donald Stewart". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ "No. 24886". The London Gazette. 28 September 1880. p. 5069.

- ↑ "The Story of Lord Roberts by Edmund Francis Sellar". 1906. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "No. 24947". The London Gazette. 8 March 1881. p. 1071.

- ↑ "No. 24984". The London Gazette. 14 June 1881. p. 3002.

- ↑ "No. 25034". The London Gazette. 4 November 1881. p. 5401.

- ↑ "No. 25268". The London Gazette. 11 September 1883. p. 4452.

- ↑ "No. 25546". The London Gazette. 5 January 1886. p. 65.

- ↑ "No. 25673". The London Gazette. 15 February 1887. p. 787.

- ↑ "No. 25773". The London Gazette. 5 January 1888. p. 219.

- ↑ "No. 26109". The London Gazette. 25 November 1890. p. 6463.

- ↑ "No. 26239". The London Gazette. 1 January 1892. p. 4.

- ↑ "No. 26260". The London Gazette. 23 February 1892. p. 990.

- ↑ "No. 26409". The London Gazette. 3 June 1893. p. 3252.

- ↑ "No. 26667". The London Gazette. 1 October 1895. p. 5406.

- ↑ "No. 26628". The London Gazette. 25 May 1895. p. 3080.

- ↑ "Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Forty-one Years in India: from Subaltern to Commander-in-chief 1897, reprinted by Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 2005

- ↑ Chronicle of the 20th Century by John S Bowman

- ↑ "No. 27146". The London Gazette. 22 December 1899. p. 8541.

- ↑ Daily Mail, 16 November 1914.

- ↑ "No. 27160". The London Gazette. 2 February 1900. p. 689.

- ↑ "From the Front, AB Paterson's Dispatches from the Boer War", edited by RWF Droogleever, Pan MacMillan Australia, 2000.

- ↑ Pakenham, p. 574.

- ↑ Heathcote 1999, p193

- ↑ "Concentration camps". Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ "The Transvaal. The attacks on the lines of communications". Evening Telegraph (Dundee). 23 July 1900. Available from the database, British Library Newspapers (Gale Primary Sources).

- ↑ Pakenham, p. 575; Heathcote, p. 249.

- ↑ "No. 27290". The London Gazette. 1 March 1901. p. 1498.

- ↑ "No. 27283". The London Gazette. 12 February 1901. p. 1058.

- ↑ "No. 27293". The London Gazette. 17 March 1901. p. 1763.

- ↑ "No. 27330". The London Gazette. 5 July 1901. p. 4469.

- ↑ "No. 27311". The London Gazette. 7 May 1901. p. 3124.

- ↑ "Emperor's visit". The Times. No. 36371. London. 6 February 1901. p. 7.

- ↑ "The Coronation Honours". The Times. No. 36804. London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36842. London. 9 August 1902. p. 6.

- ↑ "No. 27470". The London Gazette. 2 September 1902. p. 5679.

- ↑ "No. 27263". The London Gazette. 4 January 1901. p. 83.

- ↑ Atwood, Rodney. "'Across our fathers' graves': Kipling and Field-Marshall Lord Roberts". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "The German maneuvers". The Times. No. 36865. London. 5 September 1902. p. 6.

- ↑ The Pilgrims of Great Britain: A Centennial History (2002) – Anne Pimlott Baker, ISBN 1-86197-290-3.

- ↑ SHOT Backwards Design Company. "W. W. Greener Martini Target Rifles". Rifleman.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ James 1954, p. 424.

- ↑ James 1954, pp. 449–451.

- ↑ James 1954, p. 457.

- ↑ James 1954, p. 458.

- ↑ A. J. A. Morris, The Scaremongers. The Advocacy of War and Rearmament 1896–1914 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), p. 320.

- ↑ John Terraine, Impacts of War: 1914 & 1918 (London: Leo Cooper, 1993), p. 36.

- ↑ Terraine, p. 36.

- ↑ Terraine, p. 38.

- ↑ "History of "Kandahar"". Kandahar-taos.com. 11 January 1911. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, "Switzerland: Strap on the poultice" 20 January 2001 Archived 28 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "From Afghanistan to Vermont; By Allen Adler". Vermontskimuseum.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "History of Alpine Skiing". Wamonline.com. 1 May 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "No. 27316". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 May 1901. p. 3550.

- ↑ "No. 28401". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 July 1910. p. 5481.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 166.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, pp. 179–180.

- 1 2 Holmes 2004, pp. 181–183.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ Harper's Magazine, European Edition, December 1897, p. 27.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 189.

- ↑ Spark, Stephen (December 2016). "Forum". Backtrack. 30 (12): 765.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ "No. 28114". The London Gazette. 28 February 1908. p. 1402.

- ↑ "No. 25741". The London Gazette. 23 September 1887. p. 5101.

- ↑ "No. 25888". The London Gazette. 28 December 1888. p. 7421.

- ↑ "No. 26504". The London Gazette. 17 April 1894. p. 2176.

- ↑ "No. 26717". The London Gazette. 3 March 1896. p. 1271.

- ↑ "No. 26791". The London Gazette. 3 November 1896. p. 6008.

- ↑ "No. 26924". The London Gazette. 31 December 1897. p. 7856.

- ↑ "No. 27172". The London Gazette. 9 March 1900. p. 1632.

- ↑ "No. 27226". The London Gazette. 4 September 1900. p. 5469.

- ↑ "No. 27238". The London Gazette. 16 October 1900. p. 6324.

- ↑ "No. 27357". The London Gazette. 20 September 1901. p. 6175.

- ↑ "No. 27598". The London Gazette. 18 September 1903. p. 5791.

- ↑ "No. 28180". The London Gazette. 25 September 1908. p. 6944.

- ↑ "No. 28188". The London Gazette. 23 October 1908. p. 7652.

- ↑ "No. 28180". The London Gazette. 25 September 1908. p. 6946.

- ↑ "No. 28253". The London Gazette. 21 May 1909. p. 3874.

- ↑ "No. 28200". The London Gazette. 27 November 1908. p. 9032.

- ↑ "No. 28969". The London Gazette. 10 November 1914. p. 9135.

- ↑ "No. 28520". The London Gazette. 8 August 1911. p. 5919.

- ↑ "Freedom Roll" (PDF). City of Cardiff. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Portsmouth". The Times. No. 36907. London. 24 October 1902. p. 3.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts and Sir J. French at Canterbury". The Times. No. 36857. London. 27 August 1902. p. 9.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Dover". The Times. No. 36859. London. 29 August 1902. p. 10.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Bath". The Times. No. 36884. London. 27 September 1902. p. 6.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Winchester". The Times. No. 36895. London. 10 October 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener in Liverpool". The Times. No. 36897. London. 13 October 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Croydon". The Times. No. 36899. London. 15 October 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts at Bournemouth". The Times. No. 36906. London. 23 October 1902. p. 6.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener in the City". The Times. No. 36893. London. 8 October 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36919. London. 7 November 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Honorary Fellowship". Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ Heathcote, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Codell, Julie F. (2012). Transculturation in British Art, 1770-1930. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409409779.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts statue". Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ↑ "British Pathe news".

- ↑ Tabor, inside front cover

- ↑ "Hermes UAV reaches 30,000-hour milestone in Afghanistan". Ministry of Defence. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Communists to boycott poll in Robertsganj". The Times of India. 2 April 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Welcome to Lord Roberts French Immersion Public School". Lord Roberts French Immersion Public School. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Welcome to Lord Roberts Junior Public School". Lord Roberts Junior Public School. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Our mission statement". Lord Roberts Elementary School. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Lord Roberts School – Our School". Lord Roberts School. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Structure". Duke of York's Royal Military School. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Brief History". National Smallbore Rifle Association. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Voortrekkerhoogte, Tvl". Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Vol. 11. Nasou Limited. 1971. pp. 282–3. ISBN 978-0-625-00324-2.

- ↑ "The 1998 speech by South Africa's Minister of Defence on the renaming of Voortrekkerhoogte to Thaba Tshwane". South African Government. Archived from the original on 11 April 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Fuller: "Some South African Scenes and Flowers." page 63, "The Victorian Naturalist" Vol XXXII August 1915

- ↑ "The grave of Vonolel, the famous and bemedalled horse". 22 June 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

References

- Atwood, Rodney (2008). The March to Kandahar: Roberts in Afghanistan. Pen & Sword publishing. ISBN 978-1-84884-672-2.

- Atwood, Rodney (2011). Roberts and Kitchener in South Africa. Pen & Sword publishing. ISBN 978-1-84884-483-4.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 403–405.

- Hannah, W. H. (1972). Bobs, Kipling's General: The Life of Field-Marshal Earl Roberts of Kandahar, V.C. London: Lee Cooper. ISBN 085052038X. OCLC 2681649.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals 1736–1997. Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84614-0.

- James, David (1954). The Life of Lord Roberts. London: Hollis & Carter.

- Low, Charles Rathbone (1883). Major-General Sir Frederick Roberts: a Memoir. London, W.H. Allen & Co. ASIN B008UD4EBK.

- Orans, Lewis P. "Lord Roberts of Kandahar. Biography". The Pine Tree Web. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1991). The Scramble for Africa. Abacus. ISBN 978-0349104492.

- Roberts, Frederick Sleigh (1895). The Rise of Wellington. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co. OCLC 2181145.

- Roberts, Frederick Sleigh (1896). Forty-One Years in India. London: Richard Bentley and Son. ISBN 978-1402177422.

- Sellar, Edmund Francis (1906). The Story of Lord Roberts, The Children's Heroes Series No.14. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

- Tabor, Paddy (2010). The Household Cavalry Museum. Ajanta Book Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84820-882-7.

- Vibart, H.M. (1894). Addiscombe: its heroes and men of note. Westminster: Archibald Constable. pp. 592–603. OL 23336661M.

External links

- Works by Frederick Sleigh Roberts at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frederick Sleigh Roberts at Internet Archive

- Lord Roberts' British Honours

- Account of Earl Roberts' funeral

- Frederick Roberts and the long road to Kandahar

- National Portrait Gallery: Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts (1832–1914), Field Marshal

- Newspaper clippings about Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)