| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

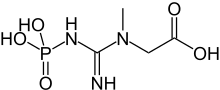

| IUPAC name

N-Methyl-N-(phosphonocarbamimidoyl)glycine | |

| Other names

Creatine phosphate; phosphorylcreatine; creatine-P; phosphagen; fosfocreatine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| Abbreviations | PCr |

| 1797096 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.585 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H10N3O5P | |

| Molar mass | 211.114 g·mol−1 |

| Pharmacology | |

| C01EB06 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Phosphocreatine, also known as creatine phosphate (CP) or PCr (Pcr), is a phosphorylated form of creatine that serves as a rapidly mobilizable reserve of high-energy phosphates in skeletal muscle, myocardium and the brain to recycle adenosine triphosphate, the energy currency of the cell.

Chemistry

In the kidneys, the enzyme AGAT catalyzes the conversion of two amino acids — arginine and glycine — into guanidinoacetate (also called glycocyamine or GAA), which is then transported in the blood to the liver. A methyl group is added to GAA from the amino acid methionine by the enzyme GAMT, forming non-phosphorylated creatine. This is then released into the blood by the liver where it travels mainly to the muscle cells (95% of the body's creatine is in muscles), and to a lesser extent the brain, heart, and pancreas. Once inside the cells it is transformed into phosphocreatine by the enzyme complex creatine kinase.

Phosphocreatine is able to donate its phosphate group to convert adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This process is an important component of all vertebrates' bioenergetic systems. For instance, while the human body only produces 250 g of ATP daily, it recycles its entire body weight in ATP each day through creatine phosphate.

Phosphocreatine can be broken down into creatinine, which is then excreted in the urine. A 70 kg man contains around 120 g of creatine, with 40% being the unphosphorylated form and 60% as creatine phosphate. Of that amount, 1–2% is broken down and excreted each day as creatinine.

Phosphocreatine is used intravenously in hospitals in some parts of the world for cardiovascular problems under the name Neoton, and also used by some professional athletes, as it is not a controlled substance.

Function

Phosphocreatine can anaerobically donate a phosphate group to ADP to form ATP during the first five to eight seconds of a maximal muscular effort. Conversely, excess ATP can be used during a period of low effort to convert creatine back to phosphocreatine.

The reversible phosphorylation of creatine (i.e., both the forward and backward reaction) is catalyzed by several creatine kinases. The presence of creatine kinase (CK-MB, creatine kinase myocardial band) in blood plasma is indicative of tissue damage and is used in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction.[1]

The cell's ability to generate phosphocreatine from excess ATP during rest, as well as its use of phosphocreatine for quick regeneration of ATP during intense activity, provides a spatial and temporal buffer of ATP concentration. In other words, phosphocreatine acts as high-energy reserve in a coupled reaction; the energy given off from donating the phosphate group is used to regenerate the other compound - in this case, ATP. Phosphocreatine plays a particularly important role in tissues that have high, fluctuating energy demands such as muscle and brain.

History

The discovery of phosphocreatine[2][3] was reported by Grace and Philip Eggleton of the University of Cambridge[4] and separately by Cyrus Fiske and Yellapragada Subbarow of the Harvard Medical School[5] in 1927. A few years later David Nachmansohn, working under Meyerhof at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Dahlem, Berlin, contributed to the understanding of the phosphocreatine's role in the cell.[3]

References

- ↑ Schlattner U, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Wallimann T (2006). "Mitochondrial creatine kinase in human health and disease". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1762 (2): 164–180. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.09.004. PMID 16236486.

- ↑ Saks, Valdur (2007). Molecular system bioenergetics: energy for life. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-527-31787-5.

- 1 2 Ochoa, Severo (1989). Sherman, E. J.; National Academy of Sciences (eds.). David Nachmansohn. Biographical Memoirs. Vol. 58. National Academies Press. pp. 357–404. ISBN 978-0-309-03938-3.

- ↑ Eggleton, Philip; Eggleton, Grace Palmer (1927). "The inorganic phosphate and a labile form of organic phosphate in the gastrocnemius of the frog". Biochemical Journal. 21 (1): 190–195. doi:10.1042/bj0210190. PMC 1251888. PMID 16743804.

- ↑ Fiske, Cyrus H.; Subbarao, Yellapragada (1927). "The nature of the 'inorganic phosphate' in voluntary muscle". Science. 65 (1686): 401–403. Bibcode:1927Sci....65..401F. doi:10.1126/science.65.1686.401. PMID 17807679.