The fortified position of Namur (French: position fortifiée de Namur [PFN]) was established by Belgium after the First World War to fortify the traditional invasion corridor between Germany and France through Belgium. The position incorporated the fortress ring of Namur, originally designed by the Belgian General Henri Alexis Brialmont to deter an invasion of Belgium by France. The old fortifications consisted of nine forts built between 1888 and 1892 on either side of the Meuse, around Namur.

Before the Second World War the forts were modernized to address shortcomings exposed during the 1914 Battle of Liège and the short siege of Namur. While the Namur defenses continued nominally to deter France from violating Belgian neutrality, the seven refurbished forts were intended as a backstop to the fortified position of Liège, which was intended to prevent a second German incursion into Belgium on the way to France. The neutrality policy and fortification programs failed and the Namur forts saw brief combat during the Battle of Belgium in 1940.

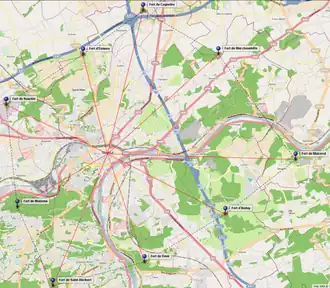

The Namur fortress ring

The first modern forts at Namur were built between 1888 and 1892 on the initiative of the Belgian General Henri Brialmont. The forts were built in a ring around Namur about 7 km (4.3 mi) from the city center. After the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), Germany and France fortified extensively their new frontier in Alsace and Lorraine. The comparatively undefended Meuse valley through Belgium provided an alternative for invasions of France or Germany. The plains of Flanders could provide transport, food and fuel for an invader and Brialmont recognized that France and Germany would once again go to war. By fortifying Liège and Namur, Belgium might deter France and Germany from fighting their next war in Belgium.[1][2] The Liège fortifications were intended to deter Germany and the Namur forts were to dissuade the French.[3]

The forts were built to standard plans and were typically triangular to minimize the number of defensive batteries in the forts' defensive ditches, presenting their apex to the attacker. Construction began on 28 July 1888 by a French consortium, Hallier, Letellier Frères and Jules Barratoux.[4] The new forts were built of concrete, a new material and were equipped with the most modern arms available in 1888. The concrete was placed in mass, without reinforcement. Lack of useful night illumination in the 1880s meant that concrete could only be placed in daylight, causing weak joints between partially cured daily pours. The forts' heavy 12 cm, 15 cm and 21 cm guns were made by the German Krupp firm, and were housed in armored steel turrets made by various French, Belgian and German firms. The forts of Liège and Namur mounted 171 heavy guns, at a cost of 29 million francs. Lighter 57 mm guns provided close defense.[5] The forts were equipped with a steam-powered electrical generating plant for lighting, pumps and searchlights.[6]

Forts

The Namur forts are arranged as follows:

- Left bank of the Meuse :

- Fort de Malonne, modernized for the PFN (50°26′40″N 04°48′30″E / 50.44444°N 4.80833°E)

- Fort de Saint-Héribert, modernized for the PFN (50°24′45″N 04°49′54″E / 50.41250°N 4.83167°E)

- Fort de Suarlée, modernized for the PFN (50°29′09″N 04°48′04″E / 50.48583°N 4.80111°E)

- Fort d'Emines, not modernized (50°30′24″N 04°51′00″E / 50.50667°N 4.85000°E)

- Fort de Cognelée, not modernized (50°31′28″N 04°53′19″E / 50.52444°N 4.88861°E)

- Fort de Marchovelette, modernized for the PFN (50°30′24″N 04°56′6″E / 50.50667°N 4.93500°E)

- Right bank of the Meuse :

- Fort de Maizeret, modernized for the PFN (50°27′49″N 04°59′13″E / 50.46361°N 4.98694°E)

- Fort d'Andoy, modernized for the PFN (50°26′28″N 04°56′30″E / 50.44111°N 4.94167°E)

- Fort de Dave, modernized for the PFN (50°25′17″N 04°53′25″E / 50.42139°N 4.89028°E)

Other fortifications of Namur, obsolete in Brialmont's time, included the Citadel of Namur. While it served no military purpose, it was used in the 1930s as the PFN command post, housed in an old tunnel network under the citadel.[7]

All of the forts were built entirely in concrete, a new material for the time, rather than the more traditional masonry. The concrete was poured in mass, without reinforcement. The forts were equipped with guns of equal or greater power than those commonly used as siege artillery in 1888, 22 cm for the French and 21 cm for the Germans. The forts' military purpose was to delay an enemy advance, allowing Belgian forces to mobilize.

Of triangular or quadrilateral form depending on the terrain, the Namur forts are identical in design to the forts of the fortified position of Liège, with a central massif with concrete cover of 3 metres (9.8 ft) to 4 metres (13 ft) thickness, surrounded by a defended ditch 8 metres (26 ft) wide. The single entries are placed in the rear or the fort, facing Namur, with a long access ramp. The entry is defended by several elements:

- A tambour with numerous gun embrasures perpendicular to the entry.

- A rolling drawbridge retracting laterally, revealing a 3.5 metres (11 ft) deep pit, equipped with grenade launchers

- The entrance grille

- A 57 mm gun firing along the axis of the gate

Each fort possessed three types of armament:

- Armored gun turrets for distant action, five to eight guns per fort

- Retractable armored gun turrets equipped with 57 mm guns for close defense, three for triangular forts, four for others

- 57 mm guns in casemates for the defense of the ditches, six to nine per fort

In 1914 each fort also possessed a detachment of infantry which in theory could make sorties onto the surrounding cleared areas to harass a besieging enemy. In practice, it was impossible to make such sorties under German artillery fire. Happily for the defenders, the dispersion of German artillery fire was considerable. At least 60% of German shells, and more for large pieces, failed to find their targets. The fortress guns were less powerful than the German guns, but were more accurate and could take advantage of observation and fire support provided by neighboring forts.

The Brialmont forts placed a weaker side to the rear to allow for recapture by Belgian forces from the rear, and located the barracks and support facilities on this side, using the rear ditch for light and ventilation of living spaces. In combat heavy shellfire made the rear ditch untenable, and German forces were able to get between the forts and attack them from the rear.[8] The forts were designed to be protected from shellfire equaling their heaviest guns: 21 cm.[9] The top of the central massif used 4 metres (13 ft) of unreinforced concrete, while the caserne walls, judged to be less exposed, used 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[10] Under fire, the forts were damaged by 21 cm weapons and could not withstand heavier artillery.[11]

The Namur forts in 1914

Namur was invested by the German Second (von Bülow) and Third (von Hausen) Armies with approximately 107,000 men on 16 August 1914. Namur was garrisoned by about 37,000 in the forts and under the Belgian 4th Division (Michel). The Belgian goal was to hold at Namur until the French Fifth Army could arrive. After attacking the Fort de Marchovelette on 20 August, the Second Army started general fire the next day. At the same time, hoping to prevent the French Fifth Army from reinforcing, the Second Army attacked in the direction of Charleroi. This action was successful, with only one French regiment making it to Namur.[12]

During the siege of Namur the Germans employed the lessons learned from their assault on the similar fortress ring of Liège. Unlike at Liège, where a quick German assault gave way to siege tactics, at Namur the Germans immediately deployed siege artillery on 21 August 1914. The guns included four Skoda 305 mm mortars Austria had given to Deutsches Kaiserreich when WWI started and 420 mm Big Bertha howitzers, firing from beyond the range of the forts' guns. The contest was unequal, and the forts suffered the same problems that plagued the Liège forts. Namur was evacuated by field forces on 23 August, the forts surrendering immediately afterwards.[12]

The Belgian forts made little provision for the daily needs of their wartime garrisons, locating latrines, showers, kitchens and the morgue in the fort's counterscarp, a location that would be untenable in combat. This had profound effects on the forts' ability to endure a long assault. These service areas were placed directly opposite the barracks, which opened into the ditch in the rear of the fort (i.e., in the face towards Liège), with lesser protection than the two "salient" sides.[13] This arrangement was calculated to place a weaker side to the rear to allow for recapture by Belgian forces from the rear, and in an age where mechanical ventilation was in its infancy, allowed natural ventilation of living quarters and support areas. However, the concept proved disastrous in practice. Heavy shellfire made the rear ditch untenable, and German forces were able to get between the forts and attack them from the rear.[8] The massive German bombardment drove men into the central massif, where there were insufficient sanitary facilities for 500 men, rendering the air unbreathable, while the German artillery destroyed the forts from above and from the rear.[14]

The Namur forts presented less of a check to the German advance than the Liège forts, as the Germans quickly assimilated the lessons of Liège and applied them to the nearly identical fortifications of Namur, but taken together the Belgian fortifications held the German advance for several days longer than the Germans had anticipated, allowing Belgium and France to mobilize, and preventing the Germans from falling on an unprepared Paris.[15]

Position fortifiée de Namur

The fortified position of Namur was conceived by a commission charged with recommending options for the rebuilding of Belgium's defenses following World War I. The 1927 report recommended the construction of a line of new fortifications to the east of the Meuse. These new forts included Fort Eben-Emael on the Belgian-Dutch-German border, designated position fortifiée de Liège I (PFL I), backed up by the renovated Liège fortress ring, PFL II. The position fortifiée de Namur (PFN) was a further fallback, while securing the road and rail crossings of the Meuse at Namur.[16]

The Belgians rebuilt seven of the Namur forts from 1929.[17] The improvements addressed the shortcomings revealed by the battles of Liège and Namur. Improvements included replacing 21 cm howitzers with longer-range 15 cm guns, 15 cm howitzers with 120 mm guns, and adding machine guns. Generating plants, ventilation, sanitation and troop accommodations were improved, as well as communications. The work incorporated alterations that had already been made by the Germans during their occupation of the forts in World War I. Most notably, the upgraded forts received defended air intake towers, intended to look like water towers, that could function as observation posts and emergency exits. The remaining two forts were used for ammunition storage.[18]

1940

During the Battle of Belgium in May 1940, the Belgian VII Corps, consisting of the 8th Infantry Division and the Chasseurs Ardennais established a strong position in the Namur defenses, anchoring the southern end of the Dyle line. However, Namur was outflanked to the south by German forces that had broken the French line at Sedan, and VII Corps pulled back without a fight to avoid entrapment.[19] The forts took initial German fire on 15 May. Marchovelette surrendered on 18 May, Suarlée on 19 May, Malonne and Saint-Héribert on 21 May, and Andoy and Maizeret on the 23rd.[20] Maizeret was targeted by German 88 mm anti-aircraft guns, which would prove to be accurate and highly effective against fixed armored targets.[21]

Present day

In contrast to the Liège fortifications, where seven of the Brialmont forts and all of the PFL forts may be visited, only one of the Namur forts is open to the public, Fort de St Heribert. It was buried for many years but since 2013 it is being excavated and restored, and can be visited the fourth Sunday of each month from April to October. All are on private or military property. Malonne is closed as a refuge for bats.[20][22] In the context of the World War I commemorative program, a project was introduced by the Namur local authorities to allow public access to Fort d'Emines (which will remain privately owned). Although the underground installation is considered unsafe by security services, counterscarp facilities and outdoor spaces will be cleared and signage will be added.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Donnell, Clayton (2007). The Forts of the Meuse in World War I. Osprey. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- ↑ Kauffmann, J.E. (1999). Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II. Combined Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 1-58097-000-1.

- ↑ "La Position Fortifiée de Liège". P.F.L. (in French). Centre Liègeois d'Histoire et d'Archéologie Militaire. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ↑ Donnell, p.9

- ↑ Donnell, p.13

- ↑ Donnell, p.17

- ↑ Puelinckx, Jean; Malchair, Luc. "Citadelle de Namur". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- 1 2 Donnell, p. 36

- ↑ Donnell, p. 52

- ↑ Donnell, p. 12

- ↑ Donnell, pp. 45-48

- 1 2 "The Siege of Namur, 1914". Battles. firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ Donnell, p.32

- ↑ Donnell, p. 52-53

- ↑ Donnell, p. 53-54

- ↑ Dunstan, pp. 11-12

- ↑ Donnell, p. 56

- ↑ Kauffmann, p. 100

- ↑ Bloock, Bernard Vanden. "Position fortifiee de Namur (PFN)". Belgian Fortifications 1940. orbat.com.

- 1 2 Lessire, Andre (22 May 2010). "La position fortifiée de Namur". L'Avenir (in French). Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ Kauffmann, p. 117

- ↑ Donnell, p. 59

- ↑ http://www.lavenir.net/article/detail.aspx?articleid=dmf20140228_00441201 L'avenir.net - De l'argent public pour un fort d'Emines toujours privé

Bibliography

- Donnell, Clayton, The Forts of the Meuse in World War I, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- Dunstan, Simon, Fort Eben Emael. The key to Hitler’s victory in the west, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2005, ISBN 1-84176-821-9.

- C. Faque, Henri-Alexis Brialmont. Les Forts de la Meuse 1887-1891, Bouge, 1987. (in French)

- Kauffmann, J.E., Jurga, R., Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II, Da Capo Press, USA, 2002, ISBN 0-306-81174-X.

External links

- Fort de St Héribert

- Belgian Fortifications, May 1940, World War II Armed Forces - Orders of Battle

- Centre liègeois d’histoire et d’archéologie militaire, Construction of the Brialmont Forts (in French)