| |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Classification | Edge-blown aerophone |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.121.12 (open side-blown flute with fingerholes) |

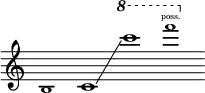

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Flutes: | |

The Western concert flute is a family of transverse (side-blown) woodwind instruments made of metal or wood. It is the most common variant of the flute. A musician who plays the flute is called a “flautist” in British English, a “flutist” in American English.[1]

This type of flute is used in many ensembles, including concert bands, military bands, marching bands, orchestras, flute ensembles, and occasionally jazz bands and big bands. Other flutes in this family include the piccolo, the alto flute, and the bass flute. A large repertory of works has been composed for flute.

Predecessors

The flute is one of the oldest and most widely used wind instruments.[2] The precursors of the modern concert flute were keyless wooden transverse flutes similar to modern fifes. These were later modified to include between one and eight keys for chromatic notes.

"Six-finger" D is the most common pitch for keyless wooden transverse flutes, which continue to be used today, particularly in Irish traditional music and historically informed performances of early music, including Baroque. During the Baroque era the traditional transverse flute was redesigned and eventually developed as the modern traverso.

Medieval flutes (1000–1400)

Throughout the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, transverse flutes were very uncommon in Europe, with the recorder being more prominent. The transverse flute arrived in Europe from Asia via the Byzantine Empire, where it migrated to Germany and France. These flutes became known as "German flutes" to distinguish them from others, such as the recorder.[3] The flute became used in court music, along with the viol, and was used in secular music, although only in France and Germany. It would not spread to the rest of Europe for nearly a century. The first literary appearance of the transverse flute was made in 1285 by Adenet le Roi in a list of instruments he played. After this, a period of 70 years follows in which few references to the flute are found.

Renaissance to 17th century

Beginning in the 1470s, a military revival in Europe led to a revival in the flute. The Swiss army used flutes for signalling, and this helped the flute spread to all of Europe.[4] In the late 16th century, flutes began to appear in court and theatre music (predecessors of the orchestra), and the first flute solos.

Following the 16th-century court music, flutes began appearing in chamber ensembles. These flutes were often used as the tenor voice. However, flutes varied greatly in size and range. This made transposition necessary, which led flautists to use Guidonian hexachords (used by singers and other musicians since their introduction in the 11th century) to transpose music more easily.[5]

During the 16th and early 17th centuries in Europe, the transverse flute was available in several sizes, in effect forming a consort in much the same way recorders and other instruments were used in consorts. At this stage, the transverse flute was usually made in one section (or two for the larger sizes) and had a cylindrical bore. As a result, this flute had a rather soft sound and was used primarily in the "soft consort".

Traverso

During the Baroque period, the transverse flute was redesigned. Now often called the traverso (from the Italian), it was made in three or four sections or joints (the head, upper-body, lower-body and foot joint).[6] Additionally, the traverso was made with a conical bore from the head joint down.[6] This conical bore design gave the flute a wider range and more penetrating sound without sacrificing the softer, expressive qualities.[6] The head joint of the traverso contains one embouchure hole across which air is blown. Additionally, the two body pieces (upper-body and lower-body) each contain three equally sized finger holes. There is one key on the baroque flute and it is on the foot-joint. This key is usually made out of metal.[6] The traverso was made with a variety of materials including various types of wood, most often boxwood, as well as ivory and metal.[7] While very few flutes remain from the Renaissance and Medieval eras, many Baroque flutes have been preserved.[7]

The role of the flute began to change as well. During the Renaissance and Medieval eras, the flute was often only used in ensembles and group performances. With the onset of the Baroque era, the traverso began to take on a role as a soloist.[8]

In the Baroque era, composers began to write more music for the flute, such as operas, ballets, chamber music, and even solos.[8] The first written work for the solo traverso was a piece written by Michael de la Barre entitled “Pièces pour la flute traversiere avec la basse-continue” in 1702.[9] Other notable baroque flute composers include, Praetorius, Schütz, Rebillé, Quantz, J.S Bach, Telemann, Blavet, Vivaldi, Hotteterre, Handel and Frederick the Great.[10] Aside from the composition of new music, several books were published during this time that dove into the study of the Baroque flute. In 1707, Jacques Martin Hotteterre wrote the first method book on playing the flute: Principes de la flûte traversière.[11] The 1730s brought an increase in operatic and chamber music feature of flutes. The end of this era found the publication of Essay of a Method of Playing the Transverse Flute by Quantz.[12]

When compared to the modern flute, the Baroque flute requires less airflow, and produces much softer, mellower sounds: often blending in with other instruments in the orchestra.[12] Additionally, when compared to the modern flute, the baroque flute requires the player to adjust with each note in order to make sure it is in tune. More adjustments are needed when playing notes outside of the D major scale. The flutist can change this pitch through small adjustments in the mouth and by turning the flute towards or away from the player.[12] This need for continued adjustment was alleviated with the creation of more modern flutes.

With the onset of the Romantic era, flutes began to lose favor: symphony orchestras rather featured brass and strings.[6] However, the 21st century has brought a rise in the popularity of the Baroque flute, most notably led by flutist Barthold Kuijken, and others such as Frans Bruggen, Emi Ferguson, Peter Holtslag.[13] These baroque flutists perform in popular Baroque orchestras that travel the world playing music using Baroque instruments and performance techniques.

Development

Boehm flute

In the nineteenth century, the great flautist, composer, acoustician, and silversmith Theobald Boehm began to make flutes. Keys were added to the flute, and the taper was changed to strengthen its lower register.[14] The dimensions and key system of the modern western concert flute and its close relatives are strongly influenced by Boehm's design, which he patented in 1847. Minor additions to and variations on his key system are common, but the acoustical structure of the tube remains almost exactly as he designed it. Major innovations were the change to metal instead of wood, large straight tube bore, "parabolic" tapered headjoint bore, very large tone holes covered by keys, and the linked key system, which simplified fingering somewhat. The most substantial departures from Boehm's original description are the universal elimination of the "crutch" for the left hand and almost universal adoption of Briccialdi's thumb key mechanism and a closed-standing G♯ key over an additional G♯ tone hole.[15] Boehm's key system, with minor variations, remains regarded as the most effective system of any modern woodwind, allowing trained instrumentalists to perform with facility and extraordinary velocity and brilliance in all keys.

The modern flute has three octaves plus C7–C♯7–D7 in the fourth octave. Many modern composers used the high D♯7; while such extremes are not commonly used, the modern flute can perform up to an F♯7 in its fourth octave.

19th-century variants

The Meyer flute was a popular flute in the mid 19th century. Including and derived from the instruments built by H.F. Meyer from 1850 to the late 1890s, it could have up to 12 keys and was built with head joints of either metal-lined ivory or wood. The final form was a combination of a traditional keyed flute and the Viennese flute, and became the most common throughout Europe and America. This form had 12 keys, a body of wood, a head joint of metal and ivory, and was common at the end of the century.[16]

Quite at the opposite end of the spectrum, in terms of the complexity of the key system developed by Boehm, was the Giorgi flute, an advanced form of the ancient holed flute. Patented in 1897, the Giorgi flute was designed without any mechanical keys, though the patent allows for the addition of keys as options. Giorgi enabled the performer to play equally true in all musical keys, as does the Boehm system. Giorgi flutes are now rarities, found in museums and private collections. The underlying principles of both flute patterns are virtually identical, with tone holes spaced as required to produce a fully chromatic scale. The player, by opening and closing holes, adjusts the effective length of the tube, and thus the rate of oscillation, which defines the audible pitch.

Modified Boehm flute

In the 1950s, Albert Cooper modified the Boehm flute to make playing modern music easier. The flute was tuned to A440, and the embouchure hole was cut in a new way to change the timbre. These flutes became the most used flutes by professionals and amateurs.[17]

In the 1980s, Johan Brögger modified the Boehm flute by fixing two major problems that had existed for nearly 150 years: maladjustment between certain keys and problems between the G and B♭ keys. The result was non-rotating shafts, which gave a quieter sound and less friction on moving parts. Also, the modifications allowed for springs to be adjusted individually, and the flute was strengthened. The Brögger flute is only made by the Brannen Brothers[18] and Miyazawa Flutes.[19]

Characteristics

The flute is a transverse (or side-blown) woodwind instrument that is closed at the blown end. It is played by blowing a stream of air over the embouchure hole. The pitch is changed by opening or closing keys that cover circular tone holes (there are typically 16 tone holes). Opening and closing the holes produces higher and lower pitches. Higher pitches can also be achieved through over-blowing, like most other woodwind instruments. The direction and intensity of the airstream also affects the pitch, timbre, and dynamics.

The piccolo is also commonly used in Western orchestras and bands. Alto flutes, pitched a fourth below the standard flute, and bass flutes, an octave below, are also used occasionally.

- (B3) C4–C7 (F♯7)

The standard concert flute, also called C flute, Boehm flute, silver flute, or simply flute, is pitched in C and has a potential range of three and a half octaves starting from the note C4 (middle C). The flute's highest pitch is usually given as C7 or (in more modern flute literature) D7. More experienced flautists are able to reach up to F♯7, but notes above D7 are difficult to produce. Modern flutes may have a longer foot joint, a B-footjoint, with an extra key to reach B3.

From high to low, the members of the concert flute family include the following:

- Piccolo in C or D♭

- Treble flute in G

- Soprano flute in E♭

- Concert flute in C, described above

- Flûte d'amour (also called tenor flute) in B♭, A, or A♭

- Alto flute in G

- Bass flute in C

- Contra-alto flute in G

- Contrabass flute in C (also called octobass flute)

- Subcontrabass flute in G (also called double contra-alto flute) or C (also called double contrabass flute)

- Double contrabass flute in C (also called octocontrabass flute or subcontrabass flute)

- Hyperbass flute in C

Each of the above instruments has its own range. The piccolo reads music in C (like the standard flute), but sounds one octave higher. The alto flute is in the key of G, and the low register extends to the G below middle C; its highest note is a high G (4 ledger lines above the treble staff). The bass flute is an octave lower than the concert flute, and the contrabass flute is an octave lower than the bass flute.

Less commonly seen flutes include the treble flute in G, pitched one octave higher than the alto flute; soprano flute, between the treble and concert; and tenor flute or flûte d'amour in B♭, A or A♭ pitched between the concert and alto.

Flutes pitched lower than the bass flute were developed in the 20th century. These include the contra-alto flute (pitched in G, one octave below the alto), the subcontrabass flute (pitched in G, two octaves below the alto), and the double contrabass flute (pitched in C, one octave below the contrabass). The flute sizes other than the concert flute and piccolo are sometimes called harmony flutes.

Construction and materials

Concert flutes have three parts: the headjoint, body, and foot joint.[20] The headjoint is sealed by a cork (or plug that may be made out of various plastics, metals, or less commonly woods). It is possible to make fine adjustments to tuning by adjusting the headjoint cork, but usually it is left in the factory-recommended position around 17.3 mm (0.68 in) from the centre of the embouchure hole for best scale. Gross, temporary adjustments of pitch are made by moving the headjoint in and out of the headjoint tenon. The flautist makes fine or rapid adjustments of pitch and timbre by adjusting the embouchure and/or position of the flute in relation to himself or herself, i.e., side and out.

- Crown – the cap at the end of the head joint that unscrews to expose the cork and helps keep the head joint cork positioned at the proper depth.

- Lip plate – the part of the head joint that contacts the player's lower lip, allowing positioning and direction of the air stream.

- Riser – the metal section that raises the lip plate from the head joint tube.

- Head joint – the top section of the flute, it has the tone hole/lip plate where the player initiates the sound by blowing air across the opening.

- Body – the middle section of the flute with the majority of the keys.

- Closed-hole – a fully covered finger key.

- Open-hole – a finger key with a perforated center.

- Pointed arms – arms connecting the keys to the rods, which are pointed and extend to the keys' centers. These are found on more expensive flutes.

- French model – a flute with pointed French-style arms and open-hole keys, as distinguished from the plateau style with closed holes.

- Inline G – the standard position of the left-hand G (third-finger) key – in line with the first and second keys.

- Offset G – a G key extended to the side of the other two left-hand finger keys (along with the G♯ key), making it easier to reach and cover effectively.

- Split E mechanism – a system whereby the second G key (positioned below the G♯ key) is closed when the right middle-finger key is depressed, enabling a clearer third octave E; omitted from many intermediate- and professional flutes, as it can reduce the tonal quality of the third-octave F♯ (F♯6).

- Trill keys – two small teardrop shaped keys between the right-hand keys on the body; the first enables an easy C–D trill, and the second enables C–D♯. A–B♭ lever or "trill" key is located in line directly above the right first-finger key. An optional C♯ trill key that facilitates the trill from B to C♯ is sometimes found on intermediate- and professional flutes. The two trill keys are also used in playing the high B♭ and B.

- Foot joint – the last section of the flute (played farthest towards the right).

- C foot – a foot joint with a lowest note of middle C (C4); typical on student flutes.

- B foot – a foot joint with a lowest note of B below middle C (B3), which is an option for intermediate and professional flutes.

- D♯ roller – an optional feature added to the E♭ key on the foot joint, facilitating the transition between E♭/D♯ and D♭/C♯, and C.

- "Gizmo key" – an optional key on the B foot joint that helps play C7.

Head joint shape

The head-joint tube is tapered slightly towards the closed end. Theobald Boehm described the shape of the taper as parabolic. Examination of his flutes did not reveal a true parabolic curve, but the taper is more complex than a truncated cone. The head joint is the most difficult part to construct because the lip plate and tone hole have critical dimensions, edges, and angles that vary slightly between manufacturers and in individual flutes, especially where they are handmade.

Head joint geometry appears particularly critical to acoustic performance and tone,[22] but there is no clear consensus on a particular shape amongst manufacturers. Acoustic impedance of the embouchure hole appears to be the most critical parameter.[23] Critical variables affecting this acoustic impedance include: chimney length (the hole between lip-plate and head tube), chimney diameter, and radiuses or curvature of the ends of the chimney. Generally, the shorter the hole, the more quickly a flute can be played; the longer the hole, the more complex the tone. Finding a particularly good example of a flute is dependent on play-testing. Head joint upgrades are usually suggested as a way to improve the tone of an instrument.

Cheaper student models may be purchased with a curved head to allow younger children with shorter arms to play them.[24]

Tubing materials

Less expensive flutes are usually constructed of brass, polished and then silver-plated and lacquered to prevent corrosion, or silver-plated nickel silver (nickel-bronze bell metal, 63% Cu, 29% Zn, 5.5% Ni, 1.25% Ag, .75% Pb, alloyed As, Sb, Fe, Sn). Flutes that are more expensive are usually made of more precious metals, most commonly solid sterling silver (92.5% silver), and other alloys including French silver (95% silver, 5% copper), "coin silver" (90% silver), or Britannia silver (95.8% silver). It is reported[25] that old Louis Lot French flutes have a particular sound by nature of their specific silver alloy. Gold/silver flutes are even more expensive. They can be either gold on the inside and silver on the outside, or vice versa. All-gold and all-platinum flutes also exist. Flutes can also be made out of wood, with African blackwood (grenadilla or Dalbergia melanoxylon) being the most common today. Cocuswood was formerly used, but this is hard to obtain today.[26] Wooden flutes were far more common before the early 20th century. The silver flute was introduced by Boehm in 1847, but did not become common until later in the 20th century. William S. Haynes, a flute manufacturer in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, told Georges Barrère that in 1905 he made one silver flute to every 100 wooden flutes, but in the 1930s, he made one wooden flute to every 100 silver flutes.[27]

Unusual tubing materials include glass, carbon fiber, and palladium.[28]

Professionals tend to play more expensive flutes. However, the idea that different materials can significantly affect sound quality is under some contention, and some argue that different metals make less difference in sound quality than different flautists playing the same flute. Even Verne Q. Powell, a flute-maker, admitted (in Needed: A Gold Flute or a Gold Lip?[29]) that "As far as tone is concerned, I contend that 90 percent of it is the man behind the flute".

Most metal flutes are made of alloys that contain significant amounts of copper or silver. These alloys are biostatic because of the oligodynamic effect and thus suppress growth of unpleasant molds, fungi, and bacteria.

Good quality flutes are designed to prevent or reduce galvanic corrosion between the tube and key mechanism.

Pad materials

Tone holes are stopped by pads constructed of fish skin (gold-beater's skin) over felt or silicone rubber on some very low-cost or "ruggedized" flutes. Accurate shimming of pads on professional flutes to ensure pad sealing is very demanding of technician time. In the traditional method, pads are seated on paper shims sealed with shellac. A recent development is "precision" pads fitted by a factory-trained technician. Student flutes are more likely to have pads bedded in thicker materials like wax or hot-melt glue. Larger-sized closed-hole pads are also held in with screws and washers. Synthetic pads appear more water-resistant but may be susceptible to mechanical failure (cracking).

Keywork

The keys can be made of the same or different metals as the tubing, nickel silver keys with silver tubing, for example. Flute key axles (or "steels") are typically made of drill rod or stainless steel. These mechanisms need periodic disassembly, cleaning, and relubrication, typically performed by a trained technician, for optimal performance. James Phelan, a flute maker and engineer, recommends single-weight motor oil (SAE 20 or 30) as a key lubricant demonstrating superior performance and reduced wear, in preference to commercial key oils).[30]

The keywork is constructed by lost-wax castings and machining, with mounting posts and ribs silver-soldered to the tube. On the best flutes, the castings are forged to increase their strength.

Most keys have needle springs made of phosphor bronze, stainless steel, beryllium copper, or a gold alloy. The B thumb keys typically have flat springs. Phosphor bronze is by far the most common material for needle springs because it is relatively inexpensive, makes a good spring, and is resistant to corrosion. Unfortunately, it is prone to metal fatigue. Stainless steel also makes a good spring and is resistant to corrosion. Gold springs are found mostly in high-end flutes because of gold's cost.

Mechanical options

- B♭ thumb key

- The B♭ thumb key (invented and pioneered by Briccialdi) is considered standard today.[31]

- Open hole keys versus plateau keys

- Open-hole "French model" flutes have circular holes in the centers of five of the keys.[32] These holes are covered by the fingertips when the keys are depressed. Open-hole flutes are frequently chosen by concert-level flautists, although this preference is less prevalent in Germany, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Students may use temporary plugs to cover the holes until they can reliably cover the holes with the fingertips. Some flautists claim that open-hole keys permit louder and clearer sound projection in the lower register. Open-hole keys are needed for traditional Celtic music and other ethnic styles and some modern concert pieces that require harmonic overtones or "breathy" sounds. They can also facilitate alternate fingerings, "extended techniques" such as quarter-tones, glissando, and multiphonics. Closed holes (plateau keys) permit a more relaxed hand position for some flautists, which can help their playing.

- Offset G versus in-line G keys

- All of Boehm's original models had offset G keys, which are mechanically simpler, and permit a more relaxed hand position, especially for flautists with small hands. Some players prefer the hand position of the in-line G.[33] For many years there was a misperception that inline G was for "professional" flutes while offset G was for "student" models, but this stereotype has been largely debunked.[34]

- Split E

- The split E modification makes the third octave E (E6) easier to play for some flautists. A less expensive option is the "low G insert".

- B foot

- The B foot extends the range of the flute down one semitone to B3 (the B below middle C).

- Gizmo key

- Some flutes with a B foot have a "gizmo key": a device that allows closure of the B tone hole independently of the C and C♯ keys. The gizmo key makes C7 easier to play.[35]

- Trill keys

- The three standard trill keys permit rapid alternation between two notes with disparate standard fingerings: lowest, middle, and highest trill keys ease C–D♯, C–D, and B♭–A, respectively.[36] Some higher notes (third-octave B and B♭ and most fourth-octave notes) also require use of the two lower trill keys. A fourth so-called C♯ trill key is an increasingly popular option available on many flutes. It is named after one of its uses, to ease the B to C♯ trill, but it also allows some trills and tremolos that are otherwise very difficult, such as high G to high A.[37] Another way of trilling G6–A6 is a dedicated high G–A trill key.[38]

- D♯ roller

- Some models offer a D♯ roller option, or even an optional pair of parallel rollers on the D♯ and C♯ keys, that ease motion of the right little finger on, for example, low C to D♯.

- Soldered tone holes

- Tone-holes may be either drawn (by pulling the tube material outwards) or soldered (cutting a hole in the tube and soldering an extra ring of material on). Soldered tone-holes are thought by some to improve tone, but generally cost more.

- Scale and pitch

- The standard pitch has varied widely over history,[39] and this has affected how flutes are made.[17] Although the standard concert pitch today is A4 = 440 Hz, many manufacturers optimize the tone hole size/spacings for higher pitch options such as A4 = 442 Hz or A4 = 444 Hz. (As noted above, adjustments to the pitch of one note, usually the A4 fingering, can be made by moving the headjoint in and out of the headjoint tenon, but the point here is that the mechanical relationship of A4 to all other pitches is set when the tone holes are cut. However, small deviations from the objective 'mechanical' pitch (which is related to acoustic impedance of a given fingering) can be improvised by embouchure adjustments.)

Composition

Classical music

An early version of Antonio Vivaldi's La tempesta di mare flute concerto was possibly written around 1713–1716, and would thus have been the first concerto for the instrument, as well as the earliest scoring of a high F6, a problematic note for the Baroque flute of that period.[40]

Pop, jazz, and rock

Flutes were rarely used in early jazz. Drummer and bandleader Chick Webb was among the first to use flutes in jazz, beginning in the late 1930s. Frank Wess was among the first noteworthy flautists in jazz, in the 1940s.[41] Since Theobald Boehm's fingering is used in saxophones as well as in concert flutes, many flute players "double" on saxophone for jazz and small ensembles and vice versa.

Since 1950, a number of notable performers have used flutes in jazz. Frank Foster and Frank Wess (Basie band), Jerome Richardson (Jones/Lewis big band) and Lew Tabackin (Akiyoshi/Tabackin big band) used flutes in big band contexts. In small band contexts, notable performers included Bud Shank, Herbie Mann, Yusef Lateef, Mélanie De Biasio, Joe Farrell, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Charles Lloyd, Hubert Laws and Moe Koffman. Several modal jazz and avant-garde jazz performers have utilized the flute including Eric Dolphy, Sam Rivers and James Spaulding.

Jethro Tull is probably the best-known rock group to make regular use of the flute, which is played by its frontman, Ian Anderson.[42] An alto flute is briefly heard in The Beatles song "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away", played by John Scott. The Beatles would later feature a flute more prominently in their single "Penny Lane".

Other groups that have used the flute in pop and rock songs include The Moody Blues, Chicago, Australian groups Men at Work and King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, the Canadian progressive rock group Harmonium, Dutch bands Focus and early Golden Earring, and the British groups Traffic, Genesis, Gong (although its flautist/saxophonist Didier Malherbe was French), Hawkwind, King Crimson, Camel, and Van der Graaf Generator.

American singer Lizzo is also well known for playing the flute. Her instrument is named Sasha Flute, which has its own Instagram account.[43]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Flutist or Flautist – Which is Correct?". Writing Explained. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ "Wind instrument - The history of Western wind instruments". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ Powell, Ardal, Dr. "Medieval flutes". FluteHistory.com. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Powell, Ardal, Dr. "Military flutes". FluteHistory.com. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Powell, Ardal, Dr. "Renaissance flutes". FluteHistory.com. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Montagu, Jeremy; Brown, Howard Mayer; Frank, Jaap; Powell, Ardal (2001). Flute. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40569.

- 1 2 Reisenweaver, Anna (2011). "The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era". Musical Offerings. 2 (1): 11–21. doi:10.15385/jmo.2011.2.1.2. ISSN 2330-8206.

- 1 2 Powell, Ardal (2001). Transverse flute. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.28275.

- ↑ Vovelle, Michel (2007). "Variations pour flûte sur la fin des lumières". Annales historiques de la Révolution française. 349 (1): 3–28. doi:10.3406/ahrf.2007.3099. ISSN 0003-4436.

- ↑ Vervliet, S.; Van Looy, B. (1 May 2010). "Bach's chorus revisited: historically informed performance practice as 'bounded creativity'". Early Music. 38 (2): 205–214. doi:10.1093/em/caq021. ISSN 0306-1078.

- ↑ "Principes de la flute traversiere ou flute d'Allemagne, de la flute a bec ou flute douce, et du haut-bois, divisez par traitez". Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 Quantz, Johann Joachim (1966). On playing the flute. Schirmer Books. OCLC 16720371.

- ↑ Barker, Naomi Joy (2003). Mozart; Handel; Telemann; Bach; Bach, Carl Phillip Emmanuel (eds.). "Baroque Flutes". Early Music. 31 (3): 466–468. doi:10.1093/earlyj/XXXI.3.466. ISSN 0306-1078. JSTOR 3138108.

- ↑ Powell, Ardal, Dr. "Classical flutes". FluteHistory.com. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Dorus G# key". Oldflutes.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Powell, Ardal, Dr. "19th Century flutes". FluteHistory.com. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "redirector: Larry Krantz Flute Pages". Larrykrantz.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Brögger flutes. Brannenflutes.com. Retrieved 25 February 2011

- ↑ Brögger system. Miyazawa.com. Retrieved 25 February 2011

- ↑ "How It's Made - Flute". YouTube. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ "How to fix your flute". studentinstruments.com.au. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Spell, Eldred (1983). "Anatomy of a Headjoint". The Flute Worker. ISSN 0737-8459. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Wolfe, Joe. "Acoustic impedance of the flute". Flute acoustics: an introduction.

- ↑ "Curved Head Student Flute by Gear4music". Gear4music. 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Louis Lot Analysis Archived 16 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Eldredspellflutes.com. Retrieved 25 February 2011

- ↑ "Finding Your Flute (How to Choose, Rent, Buy a New or Used Flute)". Markshep.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Goldman, Edwin Franko (1934). Band Betterment. Carl Fischer Inc. New York. p. 33

- ↑ Toff, Nancy (1996). The flute book: a complete guide for students and performer. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-510502-5.

- ↑ Higbee, Dale (1974). "Needed: A Gold Flute or a Gold Lip". Woodwind World. Vol. 13, no. 3. p. 22; quoted in Toff, Nancy (1996). "Chapter 7: Tone". The Flute Book. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780195105025.

- ↑ Phelan 2001, p. 58

- ↑ Toff, Nancy (1996). The Flute Book: A Complete Guide for Students and Performers at Google Books, page 56. New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-510502-8.

- ↑ "What kind of flute option is best, open or closed hole?". Larrykrantz.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ "Which is better, Offset or In-Line G?". Larrykrantz.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ "Miyazawa Flutes - Experience The Colors of Sound". Miyazawa.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Nancy Toff (1996). The flute book: a complete guide for students and performers. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-510502-5.

- ↑ "Flute and Piccolo Fingering Charts - The Woodwind Fingering Guide". Wfg.woodwind.org. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Edward Johnson. "The C♯ Trill". Brannenflutes.com.

- ↑ "Sankyo Flutes, mechanical options". Sankyoflutes.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ "redirector: Larry Krantz Flute Pages". Larrykrantz.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Powell, Ardal. "Vivaldi's Flutes: Federico Maria Sardelli, Vivaldi's Music for Flute and Recorder, trans. by Michael Talbot (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007)". Early Music 36, no. 1 (February 2008): 120–22.

- ↑ Scott Yanow: Frank Wess – Biography (at allmusic.com)

- ↑ "Ian Anderson's equipment, flutes". Jethrotull.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Schwartz, Danny (8 February 2019). "Lizzo's Flute, Sasha Flute, Is the Most Legendary Flute of All Time". Vulture. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

References

- Boehm, Theobald (1964). The Flute and Flute-Playing in Acoustical, Technical, and Artistic Aspects. Dayton C. Miller (trans.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21259-9.

- Kachmarchyk, Vladimir (2008). German flute art in XVIII-XIX centuries. Donetsk: Yugo-Vostok. ISBN 978-966-7271-44-2.

- Phelan, James (2001). The Complete Guide to the Flute and Piccolo. Burkart-Phelan, Inc. ISBN 0-9703753-0-1.

- Powell, Ardal, Dr. "FluteHistory.com". Retrieved 25 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rockstro, Richard Shepherd (1890). A Treatise on the Construction, the History and the Practice of the Flute, Including a Sketch of the Elements of Acoustics, and Critical Notices of Sixty Celebrated Flute-Players. London: Rudall, Carte and Co., Ltd. Second Edition, London: Rudall, Carte and Co., Ltd., 1928. Reprint of the second edition, in four volumes, Buren: Frits Knuf, 1986.

- Toff, Nancy (1996). The Flute Book: A Complete Guide for Students and Performers (second ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

- FluteHistory.com A comprehensive history of the transverse flute in Western music

- The Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection, many pictures of flutes through the ages, among other useful information

- Sir James Galway's Flute Chat Moderated flute discussion forum

- Larry Krantz Flute Pages, wide range of flute related information contributed by many professional flute players

- Jennifer Cluff Flute Articles, extensive list of articles on hard-to-find flute topics

- Introducing the Baroque Flute on YouTube

- Nina Perlove YouTube Channel, teaching tips, performances, vlogs, etc.

- FluteInfo Contains fingering charts, performance articles, free sheet music and other musical information

- The Woodwind Fingering Guide, large, easy-to-navigate listing of flute fingerings

- Flute Acoustics, a scientific explanation of flute acoustics

- The Virtual Flute, immense database of standard and alternative fingerings, including quarter-tones and multiphonics

- Vibrato, an essay including a collection of normal speed and slowed down audio clip of various vibrato techniques.

- An Illustrated Basic Flute Repair Manual for Professionals PDF of Thesis for Doctor of Musical Arts by Horng-Jiun Lin, M.Mus.

- FluteTunes.com Database of free sheet music for the flute

- IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library Public domain sheet music – Scores featuring the Flute