Italians of Croatia are an autochthonous historical national minority recognized by the Constitution of Croatia. As such, they elect a special representative to the Croatian Parliament.[1] There is Italian Union of Croatia and Slovenia, in Croat Talijanska Unija, in Slovene Italijanska Unija, which is Croat-Slovene organization with main site in Fiume-Rijeka and secondary site in Capodistria-Koper of Slovenia.

There are two main groups of Italians in Croatia, based on geographical origin:

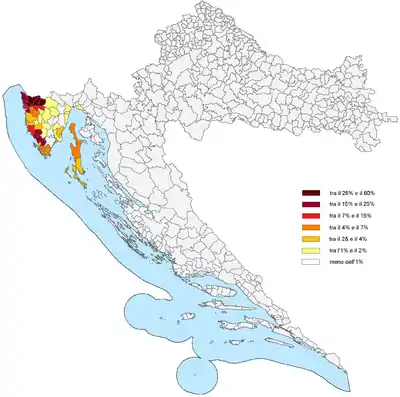

According to the 2011 Croatian census, Italians of Croatia number 17,807, or 0.42% of the total Croatian population. They mostly reside in the county of Istria.[2] As of 2010, the Italian language is co-officially used in eighteen Croatian municipalities.[3]

History

Via conquests, the Republic of Venice, from the 9th century until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon, extended its dominion to coastal parts of Istria and Dalmatia.[4] Pula/Pola was an important centre of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.[5] The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of Pula, Koper and Izola rose against the Republic of Venice but were defeated, and were since further controlled by Venice.[6] On 15 February 1267, Poreč was formally incorporated with the Venetian state.[7] Other coastal towns followed shortly thereafter. The Republic of Venice gradually dominated the whole coastal area of western Istria and the area to Plomin on the eastern part of the peninsula.[6] Dalmatia was first and finally sold to the Republic of Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia wasn't fully consolidated from 1420.[8]

From the Middle Ages onwards numbers of Slavic people near and on the Adriatic coast were ever increasing, due to their expanding population and due to pressure from the Ottomans pushing them from the south and east.[9][10] This led to Italic people becoming ever more confined to urban areas, while the countryside was populated by Slavs, with certain isolated exceptions.[11] In particular, the population was divided into urban-coastal communities (mainly Romance speakers) and rural communities (mainly Slavic speakers), with small minorities of Morlachs and Istro-Romanians.[12] From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria and Dalmatia had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" and "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.[13]

Istrian Italians were more than 50% of the total population of Istria for centuries,[14] while making up about a third of the population in 1900.[15] The Italian community at the beginning of the 20th century was still very substantial, being a majority in the most important Istrian coastal centers and in some centers in Kvarner and Dalmatia. According to the Austrian censuses, which collected the declarations relating to the language of use in 1880, 1890, 1900 and 1910, in the Istrian geographical region - which differed from the Marquisate of Istria in that the main Kvarner islands were added to the latter - Italian speakers spoke from 37.59% (1910) to 41.66% (1880) of the total population, concentrated in the western coastal areas where they also reached 90%. In Dalmatia, however, they were quite numerous only in the main cities, such as Zadar (the only Dalmatian mainland where they were majority), Split, Trogir, Sibenik, Ragusa and Kotor, and in some islands such as Krk, Cres, Lošinj, Rab, Lissa and Brazza. In these they were majorities in the centers of Cres, Mali Lošinj, Veli Lošinj and, according to the 1880 census, in the cities of Krk and Rab.

In Rijeka the Italians were the relative majority in the municipality (48.61% in 1910), and in addition to the large Croatian community (25.95% in the same year), there was also a fair Hungarian minority (13.03%).

With the awakening of national consciences (second half of the nineteenth century), the struggle between Italians and Slavs for dominion over Istria and Dalmatia began. The Italian community in Dalmatia was almost canceled by this clash between opposing nationalisms, which saw several stages:

- Between 1848 and 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire - particularly after the loss of Veneto following the Third War of Independence (1866) - favored the establishment of the Slavic ethnic group to counter the irredentism (true or presumed) of the Italian population. During the meeting of the council of ministers on November 12, 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph fully outlined a wide-ranging plan in this regard:

His Majesty expressed the precise order that decisive action be taken against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the positions of public, judicial, master employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in Alto Adige, in Dalmatia and on the Littoral for the Germanization and the Slavicization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His majesty reminds the central offices of the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

The policy of collaboration with the local Serbs, inaugurated by the Tsaratino Ghiglianovich and the Raguseo Giovanni Avoscani, then allowed the Italians to conquer the municipal administration of Ragusa in 1899. In 1909 the Italian language was prohibited, however, in all public buildings and Italians they were ousted from the municipal administrations.[18] These interferences, together with other aiding actions to the Slavic ethnic group considered by the empire more faithful to the crown, exacerbated the situation by feeding the most extremist and revolutionary currents.

- After the First World War, with the annexation of most of Dalmatia to Yugoslavia, the exodus of some thousands of Italian Dalmatians to Zadar and Italy occurred. Italian citizenship was granted to the few remaining, concentrated mainly in Split and Ragusa following the Treaty of Rapallo (1920). Zara, whose population was mostly Italian (66.29% in the city of Zara, according to the census of 1910), was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy together with Istria in 1920. Fiume was annexed to Italy in 1924.

- For a short period during the invasion of Yugoslavia (1941-1943) the Governatorate of Dalmatia was inserted in the Kingdom of Italy, with three provinces: Zadar, Split and Kotor.

- After the Second World War, all Dalmatia and almost all of Istria were annexed to Yugoslavia. Most Italians took the road of exodus, the so-called Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, which caused the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians,[19][20] and which ran from 1943 until the late 1950s. The Italians who remained in Yugoslavia, gathered in the Italian Union, were recognized as a national minority, with their own flag.

Italian community in Croatia today

The Italians in Croatia represent a residual minority of those indigenous Italian populations that inhabited for centuries and in large numbers, the coasts of Istria and the main cities of this and the coasts and islands of Dalmatia, which were territories of the Republic of Venice. After the conquest of Napoleon and his donation of the territories that belonged to the ancient Venetian Republic to the Habsburg Empire, these Italian populations had to undergo Austro-Hungarian power. After the First World War and the D'Annunzio enterprise of Fiume many of the Istrian and Dalmatian territories passed to the Kingdom of Italy, strengthening the Italian majority in Istria and Dalmatia. These populations were of Italian language and culture, speaking Venetian dialect and lived as a majority of the population in Istria and Dalmatia until the Second World War. After the Nazi-Fascist occupation of the Balkans, Slavic-speaking populations following the partisan commander Tito started a persecution of the Italian populations that had inhabited Istria and Dalmatia for several centuries. For fear of ethnic retaliation by the Slavic populations, the majority of Italians from Istria and Dalmatia poured into a real exodus towards Trieste and Triveneto. Subsequently, many of them were transferred by the authorities of the Italian Republic to southern Lazio and Sardinia where they formed numerous local communities. 34,345 Italians live in Croatia since the census conducted in Croatia on 29 June 2014, through self-certification (Italian Union data): according to official data at the 2001 census, 20,521 declared themselves to be native Italian speakers[22] and 19,636 declared to be of Italian ethnicity[23]). The Italian Croats create 51 local Italian National Communities and are organized in the Italian Union (UI).

According to Maurizio Tremul, president of the executive council of the UI, the census data in the part in which it is asked to declare the ethnicity are a bit distorted due to a "reverential fear" towards the censors who do not use Italian nor bilingual forms. The Croatian census in 2011 used a new methodology for the first time so that anyone who was not a resident of the territory or was not found at home was not surveyed.[24]

The Italians are mainly settled in the area of Istria, the islands of Kvarner and Rijeka. In coastal Dalmatia there are only 500 left, almost all of them in Zadar and Split.

They are recognized by some municipal statutes as an indigenous population: in part of Istria (both in the Croatian Istrian region, in the four coastal municipalities of Slovenia), in parts of the region of Rijeka (Primorje-Gorski Kotar County) and in the Lošinj archipelago, while in the rest of Kvarner and in Dalmatia no particular status is granted to them.

In the city of Rijeka, where the largest Italian-language newspaper in Croatia is located, as well as some schools in Italian, officially there are about 2300 Italians, although the local Italian community in Rijeka has approximately 7500 members.

The indigenous Venetian populations (north-western Istria and Dalmatia) and the Istriot-speaking peoples of the south-western Istrian coast are included in this Italian ethnic group.

During the 19th century, a considerable number of Italian craftsmen moved to live in Zagreb and Slavonia (Požega), where many of their descendants still live. A local Community of Italians was formed in Zagreb, which mainly brings together among its members recent immigrants from Italy, as well as a fair number of Italian-speaking Istrians who have moved to the capital.

In Croatian Istria - between the towns of Valdarsa and Seiane - there is the small ethnic community of the Istroromeni or Cicci, a population originally from Romania whose language, of Latin and Romanian-like, is in danger of extinction in favor of the Croatian . During Fascism these Istrorumeni were considered ethnically Italian because of their mixing during the Middle Ages with the descendants of the Ladin populations of Roman Istria, and they were guaranteed elementary teaching in their native language.[25]

According to the 2001 census, the municipalities of Croatia with the highest percentage of Italian-speaking inhabitants were all in Istria (mainly in the areas of the former zone B of the Free Territory of Trieste):

- Grisignana: 66.11%

- Verteneglio: 41.29%

- Buie: 39.66%

- Portole: 32.11%

- Valle d'Istria: 22.54%

- Umago: 20.70%

- Dignano: 20.03%

Grisignana (in Croatian "Grožnjan") is the only town with an absolute Italian-speaking majority in Croatia: over 2/3 of citizens still speak Italian and in the 2001 census over 53% declared themselves "native Italian" , while Gallesano (in Croatian "Galižana") fraction of Dignano (in Croatian "Vodnjan") with 60% of the Italian population is the inhabited center of Istria with the highest percentage of Italians.

Towns and municipalities with over 5% of population of Italians:

| Croatian name | Italian name | 2001 Census | pct of pop. | 2011 Census | pct of pop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buje | Buie | 1,587 | 29.72 | 1,261 | 24.33 |

| Novigrad | Cittanova | 511 | 12.77 | 443 | 10.20 |

| Rovinj | Rovigno | 1,628 | 11.44 | 1,608 | 11.25 |

| Umag | Umago | 2,365 | 18.33 | 1,962 | 14.57 |

| Vodnjan | Dignano | 1,133 | 20.05 | 1,017 | 16.62 |

| Bale | Valle | 290 | 27.70 | 260 | 23.07 |

| Brtonigla | Verteniglio | 590 | 37.37 | 490 | 30.14 |

| Fažana | Fasana | 154 | 5.05 | 173 | 4.76 |

| Grožnjan | Grisignana | 402 | 51.21 | 290 | 39.40 |

| Kaštelir-Labinci | Castelliere-S. Domenica | 98 | 7.35 | 70 | 4.78 |

| Ližnjan | Lisignano | 179 | 6.08 | 168 | 4.24 |

| Motovun | Montona | 97 | 9.87 | 98 | 9.76 |

| Oprtalj | Portole | 184 | 18.76 | 122 | 14.35 |

| Višnjan | Visignano | 199 | 9.10 | 155 | 6.82 |

| Vižinada | Visinada | 116 | 10.20 | 88 | 7.60 |

| Tar-Vabriga | Torre-Abrega | Part of Poreč until 2006 | 195 | 9.80 | |

Italians in Croatia are represented by one member of parliament since 1992, by elections in special electoral unit for minorities.[26]

Incumbent Furio Radin is the only representative of Italians since introductions of the Electoral law in 1992. Before 2020 elections he announced he will run for the one last time.[27]

| No. | Representative | Party | Elections won | Term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Furio Radin | Independent | 1992 1995 2000 2003 2007 2011 2015 2016 2020 |

1992 − (2024) |

Croatisation

The Italian-Croatians have experienced a process of croatisation over the past two centuries. This process was "overwhelming" especially in Dalmatia, where in 1803 were present 92,500 Dalmatian Italians, equal to 33% of the total population of Dalmatia,[28][29] reduced in 1910 to 18,028 (2.8%).[30] In 2001 about 500 were counted, concentrated mainly in Zadar.

The Italian-Croatians practically disappeared from the islands of central and southern Dalmatia during the rule of Titus, while at the time of the Risorgimento the Italians were still numerous in Lissa and other Dalmatian islands.

Even in Dalmatian cities there was a similar decrease: in the city of Split in 1910 there were over 2,082 Italians (9.75% of the population), while today only a hundred remain around the local Community of Italians (Comunità degli Italiani)

The last blow to the Italian presence in Dalmatia and in some areas of Kvarner and Istria took place in October 1953, when the Italian schools in Communist Yugoslavia were closed and the pupils moved imperiously to the Croatian schools.

In Lagosta (in Croatian Lastovo), which belonged to the Kingdom of Italy from 1918 to 1947, there are still some Italian-Croatian families not fully Croatianized today.

Lagosta and Pelagosa (Lastovo and Palagruža)

The island of Lagosta belonged to Italy from 1920 until the end of the Second World War.[31][32] While up to 1910 the presence of Italian speakers on the island was minuscule (8 in the territory of the municipality out of a total of 1,417 inhabitants), in the 1920s and 1930s several families of Italian Dalmatians moved from the areas of Dalmatia passed to the Yugoslavia. In the 1930s, about half of the inhabitants were Italian-speaking, but emigrated almost entirely after the end of the Second World War.

Some Venetian or Italian-speaking families are still present on the island of Lesina, where the creation of an Italian Union headquarters - named after the Lesignano writer Giovanni Francesco Biondi - for all Italian-Croatians of Dalmatia has been promoted Southern.

Pelagosa (and its small archipelago) was populated together with the nearby Tremiti islands by Ferdinando II of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1843 with fishermen from Ischia, who continued to speak the dialect of origin there. The attempt failed and the few fishermen emigrated in the late nineteenth century. During Fascism, the Italian authorities transplanted some fishermen from Tremiti, who left the island when it officially passed to Yugoslavia in 1947. The Pelagosa archipelago is uninhabited.

Flag

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Proportion | 1:2[33] |

|---|---|

| Design | A vertical tricolor of green, white and red |

The Italians of Croatia have an ethnic flag. It is a flag of Italy with a 1:2 aspect ratio. The flag was introduced on the basis of decisions of Unione Italiana which acts on the territory of Slovenia and Croatia as the highest body of minority self-government of the Italian minority in Croatia and Slovenia.

Education and Italian language

In many municipalities in the Istrian region (Croatia) there are bilingual statutes, and the Italian language is considered to be a co-official language. The proposal to raise Italian to a co-official language, as in the Istrian Region, has been under discussion for years.

By recognizing and respecting its cultural and historical legacy, the City of Rijeka ensures the use of its language and writing to the Italian indigenous national minority in public affairs relating to the sphere of self-government of the City of Rijeka. The City of Fiume, within the scope of its possibilities, ensures and supports the educational and cultural activity of the members of the indigenous Italian minority and its institutions.[34]

Beside Croat language schools, in Istria there are also kindergartens in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vrsar/Orsera, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle, Vodnjan/Dignano, Pula/Pola and Labin/Albona, as well as primary schools in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vodnjan/Dignano, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle and Pula/Pola, as well as lower secondary schools and upper secondary schools in Buje/Buie, Rovinj/Rovigno and Pula/Pola, all with Italian as the language of instruction.

The city of Rijeka/Fiume in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has Italian kindergartens and elementary schools, and there is an Italian Secondary School in Rijeka.[35] The town of Mali Lošinj/Lussinpiccolo in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has an Italian kindergarten.

In Zadar, in Dalmatia/Dalmazia region, the local Community of Italians has requested the creation of an Italian-language kindergarten since 2009. After considerable government opposition,[36][37] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, in the end in 2013 it was opened hosting the first 25 children.[38] This kindergarten is the first Italian educational institution opened in Dalmatia after the closure of the last Italian school, which operated there until 1953.

Since 2017, a Croatian primary school has been offering the study of the Italian language as a foreign language. Italian courses have also been activated in a secondary school and at the faculty of literature and philosophy.[39] An estimated 14% of Croats speak Italian as a second language, which is one of the highest percentages in the European Union.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pravo pripadnika nacionalnih manjina u Republici Hrvatskoj na zastupljenost u Hrvatskom saboru". Zakon o izborima zastupnika u Hrvatski sabor (in Croatian). Croatian Parliament. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ 2011 Croatian census

- ↑ "LA LINGUA ITALIANA E LE SCUOLE ITALIANE NEL TERRITORIO ISTRIANO" (in Italian). p. 161. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Alvise Zorzi, La Repubblica del Leone. Storia di Venezia, Milano, Bompiani, 2001, ISBN 978-88-452-9136-4., pp. 53-55 (in italian)

- ↑ Prominent Istrians

- 1 2 "Historic overview-more details". Istra-Istria.hr. Istria County. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ John Mason Neale, Notes Ecclesiological & Picturesque on Dalmatia, Croatia, Istria, Styria, with a visit to Montenegro, pg. 76, J.T. Hayes - London (1861)

- ↑ "Dalmatia history". Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Region of Istria: Historic overview-more details". Istra-istria.hr. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Jaka Bartolj. "The Olive Grove Revolution". Transdiffusion. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010.

While most of the population in the towns, especially those on or near the coast, was Italian, Istria's interior was overwhelmingly Slavic – mostly Croatian, but with a sizeable Slovenian area as well.

- ↑ "Italian islands in a Slavic sea". Arrigo Petacco, Konrad Eisenbichler, A tragedy revealed, p. 9.

- ↑ ""L'Adriatico orientale e la sterile ricerca delle nazionalità delle persone" di Kristijan Knez; La Voce del Popolo (quotidiano di Fiume) del 2/10/2002" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "Istrian Spring". Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ↑ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 886–887.

- ↑ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ↑ Jürgen Baurmann; Hartmut Gunther; Ulrich Knoop (1993). Homo scribens : Perspektiven der Schriftlichkeitsforschung (in German). Tübingen. p. 279. ISBN 3484311347.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Dizionario Enciclopedico Italiano (Vol. III, p. 730), Roma, Ed. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, founded by Giovanni Treccani, 1970

- ↑ Thammy Evans & Rudolf Abraham (2013). Istria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 11. ISBN 9781841624457.

- ↑ James M. Markham (6 June 1987). "Election Opens Old Wounds in Trieste". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Census of Population, Householdes and Dwellings, 2011

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ "Il passaporto sotto al cuscino". Salto.bz. 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ↑ Another ethnic group originally of Romance language is that of the Morlacchi, a historical population deriving - according to the majority theories - from the ancient Latinized populations of the Dalmatian hinterland, subsequently Slavic.

- ↑ "Arhiva izbora" [Election archive]. Arhiva izbora Republike Hrvatske (in Croatian). Državno izborno povjerenstvo Republike Hrvatske. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ↑ "Saborski veteran Furio Radin kandidirao se po deveti put: Ovo mi je zadnje!" [Parliamentary veteran Furio Radin ran for the ninth time: This is my last!]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). 14 June 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ Bartoli, Matteo (1919). Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia (in Italian). Tipografia italo-orientale. p. 16.[ISBN unspecified]

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 9780416189407.

- ↑ Tutti i dati in Š.Peričić, O broju Talijana/talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. stoljeća, in Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru, n. 45/2003, p. 342

- ↑ "ZARA" (in Italian). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ↑ "L'11 luglio di cent'anni fa l'Italia occupava l'isola di Pelagosa" (in Italian). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ↑ The FAME: Hrvatska – nacionalne manjine

- ↑ Government use of the Italian language in Rijeka

- ↑ "Byron: the first language school in Istria". www.byronlang.net. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ↑ Reazioni scandalizzate per il rifiuto governativo croato ad autorizzare un asilo italiano a Zara

- ↑ Zara: ok all'apertura dell'asilo italiano

- ↑ Aperto “Pinocchio”, primo asilo italiano nella città di Zara

- ↑ "L'italiano con modello C a breve in una scuola di Zara". Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Directorate General for Education and Culture; Directorate General Press and Communication (2006). Europeans and their Languages (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

Literature

- Monzali, Luciano (2016). "A Difficult and Silent Return: Italian Exiles from Dalmatia and Yugoslav Zadar/Zara after the Second World War". Balcanica (47): 317–328. doi:10.2298/BALC1647317M. hdl:11586/186368.

- Ezio e Luciano Giuricin (2015) Mezzo secolo di collaborazione (1964-2014) Lineamenti per la storia delle relazioni tra la Comunità italiana in Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia e la Nazione madre