Felix Dzerzhinsky | |

|---|---|

| Feliks Dzierżyński | |

Dzerzhinsky in 1918 | |

| Chairman of the OGPU | |

| In office 15 November 1923 – 20 July 1926 | |

| Premier | |

| Preceded by | Himself as Chairman of the GPU |

| Succeeded by | Vyacheslav Menzhinsky |

| Chairman of the GPU | |

| In office 6 February 1922 – 15 November 1923 | |

| Premier | Vladimir Lenin |

| Preceded by | Himself as Chairman of the Cheka |

| Succeeded by | Himself as Chairman of the OGPU |

| Chairman of the Cheka | |

| In office 20 December 1917 – 6 February 1922 | |

| Premier | Vladimir Lenin |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Himself as Chairman of the GPU |

| People's Commissar of VSNKh | |

| In office 2 February 1924 – 20 July 1926 | |

| Premier | Alexei Rykov |

| Preceded by | Alexei Rykov |

| Succeeded by | Valerian Kuybyshev |

| Candidate member of the 13th, 14th Politburo | |

| In office 2 June 1924 – 20 July 1926 | |

| Member of the 6th Secretariat | |

| In office 6 August 1917 – 8 March 1918 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Feliks Dzierżyński 11 September [O.S. 30 August] 1877 Dzerzhinovo estate, Minsk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | July 20, 1926 (aged 48) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Political party | VKP(b) (from 1917) |

| Other political affiliations | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Jan Feliksovich |

| Signature | |

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (Polish: Feliks Dzierżyński [ˈfɛliɡz d͡ʑɛrˈʐɨj̃skʲi];[lower-alpha 1] Russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский;[lower-alpha 2] 11 September [O.S. 30 August] 1877 – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and politician. From 1917 until his death in 1926, he led the first two Soviet secret police organizations, the Cheka and the OGPU, establishing state security organs for the post-revolutionary Soviet regime. He was one of the architects of the Red Terror[2][3] and de-Cossackization.[4][5]

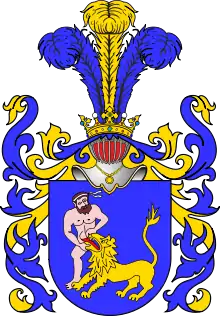

Born to a Polish family of noble descent in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now Belarus), Dzerzhinsky embraced revolutionary politics from a young age and was active in Kaunas as an organizer for the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party. He was frequently arrested and underwent several exiles to Siberia, from which he repeatedly escaped. He participated in the 1905 Russian Revolution and pursued further revolutionary activities in Germany and Poland. Following another arrest in 1912, he spent four-and-a-half years in prison before his release after the 1917 February Revolution. He then joined Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik party and played an active role in the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

In December 1917, Lenin named Dzerzhinsky head of the newly established All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (Cheka), tasking him with the suppression of counter-revolutionary activities in Soviet Russia. The Russian Civil War saw the expansion of the Cheka's authority, inaugurating a campaign of mass executions known as the Red Terror. The Cheka was reorganized as the State Political Directorate (GPU) in 1922 and then the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) a year later, with Dzerzhinsky remaining head of the powerful organization. In addition, he served as director of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy (VSNKh) from 1924.

Dzerzhinsky died of a heart attack in 1926. He became widely celebrated in the Soviet Union, Poland and other communist countries in the following decades, with numerous places (including the city of Dzerzhinsk) named in his honour, and is among the few Soviet figures to be buried in an individual tomb in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. Meanwhile, he also became a prominent symbol of repression and brutality to critics of the Soviet regime.

Early life

Felix Dzerzhinsky was born on 11 September 1877 to ethnically Polish parents of noble descent, at the Dzerzhinovo family estate, about 15 km (9.3 mi) from the small town of Ivyanets in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now Belarus).[7] In the Russian Empire, his family was of a type known as "column-listed nobility" (Russian: столбовое дворянство, stolbovoe dvorianstvo),[8] whose nobility was formally acknowledged, but so old that they did not enjoy the privileges of the new nobility.[9] His sister Wanda died at the age of 12, when she was accidentally shot with a hunting rifle on the family estate by one of her brothers. At the time of the incident, there were conflicting claims as to whether Felix or his brother Stanisław was responsible for the accident.[10]

His father, Edmund-Rufin Dzierżyński graduated from the Saint Petersburg Imperial University in 1863 and moved to Vilnius, where he worked as a home teacher for a professor of Saint Petersburg University named Januszewski and eventually married Januszewski's daughter Helena Ignatievna, who also was of Polish origin. In 1868, after a short period in Kherson gymnasium, he worked as a gymnasium teacher of physics and mathematics at the schools of Taganrog in the Don Host Province, Russia, particularly the Chekhov Gymnasium.[11] In 1875, Edmund Dzierżyński retired due to health conditions and moved with his family to his estate near Ivyanets and Rakaŭ. In 1882, Felix's father died from tuberculosis.[11]

As a youngster Dzerzhinsky became a polyglot, speaking: Polish, Russian, German and Latin. He attended the Vilnius Gymnasium from 1887 to 1895. One of the older students at this gymnasium was his future arch-enemy, Józef Piłsudski. Years later, as Marshal of Poland, Piłsudski recalled that Dzerzhinsky "distinguished himself as a student with delicacy and modesty. He was rather tall, thin and demure, making the impression of an ascetic with the face of an icon... Tormented or not, this is an issue history will clarify; in any case this person did not know how to lie."[12] School documents show that Dzerzhinsky attended his first year in school twice, while he was not able to finish his eighth year. Dzerzhinsky received a school diploma which stated: "Dzerzhinsky Feliks, who is 18 years of age, of Catholic faith, along with a satisfactory attention and satisfactory diligence showed the following successes in sciences, namely: Divine law—"good"; Logic, Latin, Algebra, Geometry, Mathematical geography, Physics, History (of Russia), French—"satisfactory"; Russian and Greek—"unsatisfactory".[13]

Political affiliations and arrests

Two months before he expected to graduate, the gymnasium expelled Dzerzhinsky for "revolutionary activity" and for posting signs with socialist slogans at the school. He had joined a Marxist group, the Union of Workers (Socjaldemokracja Królestwa Polskiego "SDKP"), in 1895. In late April 1896, he was one of 15 delegates at the first congress of the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (LSDP).[14] In 1897, he attended the second congress of the LSDP, where it rejected independence in favor of national autonomy. On 18 March 1897, he was sent to Kaunas to take advantage of the arrest of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) branch. He worked in a book-binding factory and set up an illegal press.[15] As an organizer of a shoemakers' strike, Dzerzhinsky was arrested for "criminal agitation among the Kaunas workers"; the police files from this time state: "Felix Dzerzhinsky, considering his views, convictions and personal character, will be very dangerous in the future, capable of any crime."[16] Dzerzhinsky envisioned merging the LSDP with the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and took the same position as influential Social Democrat Rosa Luxemburg on what was referred to in contemporary writings as "The National Question," i.e., the right of nations to self determination.[17]

He was arrested on a denunciation for his revolutionary activities for the first time in 1897, after which he served almost a year in the Kaunas prison. In 1898, Dzerzhinsky was exiled for three years to the Vyatka Governorate (city of Nolinsk) where he worked at a local tobacco factory. There Dzerzhinsky was arrested for agitating for revolutionary activities and was sent 500 versts (330 mi) north to the village of Kaigorod. In August 1899, he returned to Vilnius. Dzerzhinsky subsequently became one of the founders of Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (Polish: Socjaldemokracja Królestwa Polskiego i Litwy, SDKPiL) in 1899. In February 1900, he was arrested again and served his time at first in the Alexander Citadel in Warsaw and later at the Siedlce prison. In 1902, Dzerzhinsky was sent deep into Siberia for the next five years to the remote town of Vilyuysk, while en route being temporarily held at the Alexandrovsk Transitional Prison near Irkutsk. While in exile, he escaped on a boat and later emigrated from the country. He traveled to Berlin, where at the SDKPiL conference Dzerzhinsky was elected a secretary of its party committee abroad (Polish: Komitet Zagraniczny, KZ) and met with several prominent leaders of the Polish Social Democratic movement, including Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches. They gained control of the party organization through the creation of a committee called the Komitet Zagraniczny (KZ), which dealt with the party's foreign relations. As secretary of the KZ, Dzerzhinsky was able to dominate the SDKPiL. In Berlin, he organized publication of the newspaper Czerwony Sztandar ("Red Banner"), and transportation of illegal literature from Kraków into Congress Poland. Being a delegate to the IV Congress of SDKPiL in 1903, Dzerzhinsky was elected as a member of its General Board.

Dzerzhinsky visited Switzerland, where his fiancée Julia Goldman, the sister of Boris Gorev, was undergoing treatment for tuberculosis. She died in his arms on 4 June 1904. Her illness and death depressed him – in letters to his sister, Dzerzhinsky explained that he no longer saw any meaning for his life. That changed with the Russian Revolution of 1905, as Dzerzhinsky became involved with work again. After the revolution failed he was again jailed in July 1905, this time by the Okhrana. In October, he was released on amnesty. As a delegate to the 4th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in Stockholm, Dzerzhinsky entered the central body of the party. From July through September 1906, he lived in Saint Petersburg and then returned to Warsaw, where he was arrested again in December of the same year. In June 1907, Dzerzhinsky was released on bail. At the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in London in May–June 1907, he was elected in absentia as a member of the Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party. In April 1908, Dzerzhinsky was arrested once again in Warsaw and again exiled to Siberia (Yeniseysk Governorate) in 1909. As before, Dzerzhinsky managed to escape (by November 1909). In 1910, he reached Italy, where he met Maxim Gorky on Capri; he then returned to Poland.

Back in Kraków in 1910, Dzerzhinsky married RSDLP party member Zofia Muszkat, who was already pregnant. A month later she was arrested; she gave birth to their son Janek in Pawiak prison. In 1911, Zofia was sentenced to permanent Siberian exile, and she left the child with her father. Dzerzhinsky saw his son for the first time in March 1912 in Warsaw. In attending the welfare of his child, Dzerzhinsky repeatedly exposed himself to the danger of arrest. On one occasion, Dzerzhinsky narrowly escaped an ambush that the police had prepared at the apartment of his father-in-law.[18]

Dzerzhinsky continued to direct the Social Democratic Party (SDKPiL), while considering his continued freedom "only a game of the Okhrana". The Okhrana, however, was not playing a game; Dzerzhinsky simply was a master of conspiratorial techniques and was therefore extremely difficult to find. A police file from this time says: "Dzerzhinsky continued to lead the Social Democratic party and at the same time he directed party work in Warsaw, led strikes, published appeals to workers, and traveled on party matters to Łódź and Kraków." The police were unable to arrest Dzerzhinsky until the end of 1912, when they found the apartment where he lived in the name of Władysław Ptasiński.[19]

Revolution

Dzerzhinsky spent the next four-and-a-half years in prisons, first at the notorious Tenth Pavilion of the Warsaw Citadel. When World War I began in 1914, all political prisoners were relocated from Warsaw into Russia proper. Dzerzhinsky was taken to Oryol Prison. He was very concerned about the fate of his wife and son, with whom he did not have any communication. Moreover, Dzerzhinsky was beaten frequently by the Russian prison guards, which caused permanent disfigurement of his jaw and mouth. In 1916, Dzerzhinsky was moved to the Moscow Butyrka prison, where he was soon hospitalized because the chains that he was forced to wear had caused severe cramps in his legs. Despite the prospects of amputation, Dzerzhinsky recovered and was put to labor sewing military uniforms.[20]

Dzerzhinsky was freed from Butyrka after the February Revolution of 1917. Soon after his release, Dzerzhinsky's goal was to organize Polish refugees in Russia and then go back to Poland and fight for the revolution there, writing to his wife that "together with these masses we will return to Poland after the war and become one whole with the SDKPiL." He remained in Moscow where he joined the Bolshevik party, writing to his comrades that "the Bolshevik party organization is the only Social Democratic organization of the proletariat, and if we were to stay outside of it, then we would find ourselves outside of the proletarian revolutionary struggle." Already in April, he entered the Moscow Committee of the Bolsheviks and soon thereafter was elected to the Executive Committee of the Moscow Soviet. Dzerzhinsky endorsed Vladimir Lenin's "April Theses", demanding uncompromising opposition to the new Russian Provisional Government, the transfer of all political authority to the Soviets, and the immediate withdrawal of Russia from the war. Dzerzhinsky's brother Stanisław was murdered on the Dzerzhinsky estate by deserting Russian soldiers that same year.[21][22]

Dzerzhinsky was elected subsequently to the Bolshevik Central Committee at the Sixth Party Congress in late July. He then moved from Moscow to Petrograd to begin his new responsibilities. In Petrograd, Dzerzhinsky participated in the crucial session of the Central Committee in October and he strongly endorsed Lenin's demands for the immediate preparation of a coup, after which Felix Dzerzhinsky had an active role with the Military Revolutionary Committee during the October Revolution. With the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks, Dzerzhinsky eagerly assumed responsibility for making security arrangements at the Smolny Institute where the Bolsheviks had their headquarters.[23]

Director of Cheka

Lenin regarded Felix Dzerzhinsky as a revolutionary hero and appointed him to organize a force to combat internal threats. On 20 December 1917, the Council of People's Commissars officially established the All-Russia Extraordinary Commission to Combat Counter-revolution and Sabotage—commonly known as the Cheka (based on the Russian acronym ВЧК). Dzerzhinsky became its director. The Cheka received extensive resources, and became known for ruthlessly pursuing any perceived counterrevolutionary elements. As the Russian Civil War expanded, Dzerzhinsky also began organizing internal security troops to enforce the Cheka's authority.

The Cheka became notorious for mass summary executions, performed especially during the Red Terror and the Russian Civil War.[24][25] The Cheka undertook drastic measures as tens of thousands of political opponents and saboteurs were shot without trial in the basements of prisons and in public places.[26] Dzerzhinsky said: "We represent in ourselves organized terror—this must be said very clearly,"[27][28] In 1922, at the end of the Civil War, the Cheka was dissolved and reorganized as the State Political Directorate (Gosudarstvennoe Politicheskoe Upravlenie, or GPU), a section of the NKVD. With the formation of the Soviet Union later that year, the GPU was again reorganized as the Joint State Political Directorate (Obyedinyonnoye gosudarstvennoye politicheskoye upravleniye, or OGPU), directly under the Council of People's Commissars. These changes did not diminish Dzerzhinsky's power; he was Minister of the Interior, director of the Cheka/GPU/OGPU, Minister for Communications, and director of the Vesenkha (Supreme Council of National Economy) in 1921–24. Indeed, while the (O)GPU was theoretically supposed to act with more restraint than the Cheka, in time its de facto powers grew even greater than those of the Cheka.

Felix Dzerzhinsky established a "special disinformation office" within the OGPU, the reorganized Cheka, in 1923.[29] Dzerzhinsky established the office under the orders of Josef Stalin.[30]

At his office in Lubyanka, Dzerzhinsky kept a portrait of fellow Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg on the wall.[31] Besides his leadership of the secret police, Dzerzhinsky also took on a number of other roles; he led the fight against typhus in 1918, was chair of the Commissariat for Internal Affairs from 1919 to 1923, initiated a vast orphanage construction program,[32] chaired the Transport Commissariat, organized the embalming of Lenin's body in 1924 and chaired the Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema.[33]

Dzerzhinsky and Lenin

Dzerzhinsky became a Bolshevik as late as 1917. Therefore, it was wrong to assert (as official Soviet historians did subsequently) that Dzerzhinsky had been one of Lenin's oldest and most reliable comrades, or that Lenin had exercised some sort of spellbinding influence on Dzerzhinsky and the SDKPiL. Lenin and Dzerzhinsky frequently had opposing opinions about many important ideological and political issues of the pre-revolutionary period, and also after the October Revolution. After 1917, Dzerzhinsky would oppose Lenin on such crucial issues as the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the trade unions, and Soviet nationality policy. During the April 1917 Party Conference, when Lenin accused Dzerzhinsky of Great-Russian chauvinism, he replied: "I can reproach him (Lenin) with standing at the point of view of the Polish, Ukrainian and other chauvinists."[34]

From 1917 to his death in 1926, Dzerzhinsky was first and foremost a Russian Communist, and Dzerzhinsky's involvement in the affairs of the Polish Communist Party (which was founded in 1918) was minimal. The energy and dedication that had previously been responsible for the building of the SDKPiL would henceforth be devoted to the priorities of the struggle for Bolshevik power in Russia, to the defence of the revolution during the civil war, and eventually, to the tasks of socialist construction.[35]

Death and legacy

%252C_bolshevik_revolutionary_and_official._Portrait).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Dzerzhinsky died of a heart attack on 20 July 1926 in Moscow, immediately after a two-hour speech to the Bolshevik Central Committee during which, visibly quite ill, he violently denounced the United Opposition directed by Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev.[36] Upon hearing of his death, Joseph Stalin eulogized Dzerzhinsky as "a devout knight of the proletariat".[37] Dzerzhinsky was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. Today his grave is one of the twelve individual tombs located between the Lenin Mausoleum and the Kremlin Wall.

Dzerzhinsky was succeeded as chairman of the OGPU by Vyacheslav Menzhinsky.

Dzierżyńszczyzna, one of the two Polish Autonomous Districts in the Soviet Union, was named to commemorate Dzerzhinsky. Located in Belarus, near Minsk and close to the Soviet-Polish border of the time, it was created on 15 March 1932, with the capital at Dzyarzhynsk (in Russian Dzerzhynsk, formerly known as Kojdanów), not far from the family estate. The Dzerzhinsky estate itself remained inside Poland from 1921 to the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. The district was disbanded in 1935 at the onset of the Great Purge, and most of its administration was executed.

Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (the highest point in Belarus), located near Dzyarzhynsk was named after Dzerzhinsky in 1958.

His name and image were used widely throughout the KGB and the Soviet Union and other communist countries; there were numerous places named after him. In Russia, there is the city of Dzerzhinsk, a village of Dzerzhinsk, and three other cities called Dzerzhinskiy; in other former Soviet republics, there was a city named for him in Armenia and the aforementioned Dzyarzhynsk in Belarus. To comply with decommunization laws,[38] the Ukrainian cities Dzerzhynsk and Dniprodzerzhynsk reverted to their historic names Toretsk and Kamianske in February and May 2016.[39] A Ukrainian village in the Zhytomyr Oblast was also named Dzerzhinsk until 2005, when it was renamed to Romaniv. The Dzerzhinskiy Tractor Works in Stalingrad were named in his honor and became a scene of bitter fighting during the Second World War. The FED camera, produced from 1934 to around 1996, is named for him,[40] as was the FD class steam locomotive.

During the Communist era (1945–1989) in Poland, Dzerzhinsky was celebrated as a socialist hero. In 1951, a large-scale statue of Dzerzhinsky was designed by Zbigniew Dunajewski and erected in the northern side of Bank Square in Warsaw.[41] The square bore Dzerzhinsky's name (Polish: Plac Dzierżyńskiego) until 1989. The statue was toppled on 16 November 1989, one of the many Soviet-era symbols removed that year to mark the end of Communism in Poland. The square was subsequently renamed Plac Bankowy (Bank Square).[41]

Iron Felix

A 15-ton iron monument of Dzerzhinsky, which once dominated the Lubyanka Square in Moscow, near the KGB headquarters, also became known as "Iron Felix" (Russian: Железный Феликс – Zheleznyj Feliks). Sculpted in 1958 by Yevgeny Vuchetich, it served as a Moscow landmark during late Soviet times. Symbolically, the Memorial society erected the Solovetsky Stone, a memorial to the victims of the Gulag (using a simple stone from the Solovki prison camp in the White Sea) beside the Iron Felix statue on 30 October 1990). The Moscow Soviet (Mossovet) had the Dzerzhinsky statue removed to the Fallen Monument Park and laid on its side in August 1991, after the failed coup d'état attempt by hard-line Communist members of the government. A mock-up of the removal of Dzerzhinsky's statue can be found in the entrance hall of the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C.

The figure of Dzerzhinsky remains controversial in Russian society. Between 1999 and 2013, six proposals called for the return of the statue to its plinth. The Monument Art Commission of the Moscow City Duma rejected the proposals due to concerns that the proposed return would cause "unnecessary tension" in society.[42] According to a December 2013 VTsIOM poll, 46% of Russians favour the restoration of the statue to the Lubyanka Square, with 17% opposing it.[43] The statue remained in a yard for old Soviet memorials at the Central House of Artists.[44]

In April 2012, the Moscow authorities stated that they would renovate the "Iron Felix" monument in full and put the statue on a list of monuments to be renovated, as well as officially designating it an object of cultural heritage.[45] On 26 April 2021, it was announced by the prosecutor office of Moscow that the removal of the statue had no legal basis and was therefore illegal.[46]

Finally, the monument was reerected on September 11, 2023, but this time in front of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service headquarters outside Moscow.[47]

Other statues

A smaller bust of Dzerzhinsky in the courtyard of the Moscow police headquarters at Petrovka 38 was restored in November 2005 (police officers had removed this bust on 22 August 1991).

A 10-foot bronze replica of the original Iron Felix statue was placed on the grounds of the military academy in Minsk, Belarus, in May 2006.[48]

In 2017, on the 140th anniversary of Dzerzhinsky's birth, a monument to Dzerzhinsky was erected in the city of Ryazan, Russia.[49]

On 20 January 2017, the People's Public Security Academy in Hanoi, Vietnam, inaugurated a Dzerzhinsky statue.

Dzerzhinovo

In 1943, the manor house of Dzerzhinovo, where Dzerzhinsky was born, was destroyed and family members (including Dzerzhinsky's brother Kazimierz) were killed by the Germans, because of their support for the Polish Home Army. In 2005, the Government of Belarus rebuilt the house (now on Belarusian territory) and established a museum. The graduating class of the KGB academy holds its annual swearing-in at the manor.[50][22]

See also

- Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies

- Chekism

- "Dzerzhinsky Division" of the Soviet Internal Troops

- Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment now defunct military unit of the East German Ministry for State Security (commonly known as the Stasi)

- Monument to F. E. Dzerzhinsky in Taganrog

- Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee

- Polish Autonomous District

- Kang Sheng

Notes

References

- ↑ Abramovitch, Raphael (1962). The Soviet Revolution: 1917–1938. New York City: International Universities Press. ISBN 9781315401720.

- ↑ Carr, Barnes (2016). Operation Whisper: The Capture of Soviet Spies Morris and Lona Cohen. University Press of New England. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-1-61168-939-6.

- Southwell, David; Twist, Sean (2004). "The KGB". Secret Societies. Mysteries and Conspiracies. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group (published 2007). p. 60. ISBN 9781404210844. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

Dzerzhinsky was the mastermind behind the Red Terror that allowed the Communists to seize and hold on to power ...

- Ryan, James (2012). Lenin's Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 9781138815681.

Estimates of the total number of executed victims of the Terror vary. Rat'kovskii puts the figure at 8,000 for the period from 30 August until the end of the year, Nicolas Werth at between 10,000 and 15,000. The majority of the Terror's targets were former Tsarist officers and representatives of the Tsarist regime.

- Southwell, David; Twist, Sean (2004). "The KGB". Secret Societies. Mysteries and Conspiracies. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group (published 2007). p. 60. ISBN 9781404210844. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Часть IV. На гражданской войнe. // Sergei Melgunov «Красный террор» в России 1918—1923. — 2-ое изд., доп. — Берлин, 1924

- ↑ Lauchlan, Iain (2018). "A Perfect Spy Chief? Feliks Dzerzhinsky and the Cheka". In Maddrell, Paul; Moran, Christopher; Stout, Mark; Iordanou, Ioanna (eds.). Spy Chiefs. Vol. 2: Intelligence Leaders in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 9781626165236. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

The Cheka's first mass operation—'Decossackization,' the deportation in April 1919 of an estimated 300,000 people—was more akin to the actions of an invading army than a police measure; it was carried out to secure the southern front against the White armies.

- ↑ Havlat, Alexander (2011). Victims of the Bolsheviks: 1917-1953. GRIN Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 9783640797004. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

In the course of the so called deCossackization, (i.e. the planned annihilation of the Cossacks as a social class) between 300 000 and 500 000 Don Cossacks were killed or deported in the years 1919/20, out of a total population of 3 million ...

- ↑ Albert P. Nenarokov. Russia in the Twentieth Century. (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1968), 117–118.

- ↑ Фамилия: Гулухов (in Russian)

- ↑ Igor Kuznetsov. The Chekist No.1. The life of terror parent (Чекист № 1. Житие отца террора). BelGazeta. 21 July 2020

- ↑ Грамота на права, вольности и преимущества благородного российского дворянства, 21 апреля 1785 (Полное собрание законов Российской империи, Ч. I, т. XXII, № 16187; п. 82)

- ↑ Veronika Anatolievna Cherkasova. "Феликс не всегда был железным... (Feliks not always was iron...)". Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- 1 2 Plekhanov, Alexander Mikhaylovich (2007). Дзержинский. Первый чекист России [Dzerzhinsky. The First Cheikist of Russia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. p. 19. ISBN 978-5-373-01334-5.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, p. 30.

- ↑ Fedotkina, Tatiana (5 September 1998). Палач Королевства любви [The executioner of the Kingdom of love]. Moskovskij Komsomolets (in Russian). No. 71.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, p. 37

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, p. 42

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, p. 46.

- ↑ "Rosa Luxemburg: The Polish Question and the Socialist Movement (1905)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- "Rosa Luxemburg: The National Question (Chap.1)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, pp. 213–217.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 "Krasnyj pomieszczik". magwil.lt. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, pp. 213–222.

- ↑ Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, 2007. ISBN 1-4000-4005-1. pp. 46–48.

- ↑ George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-19-822862-7 pp. 197–201.

- ↑ Orlando Figes. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. Penguin Books, 1997. ISBN 0-19-822862-7. p. 647

- ↑ J. Michael Waller Secret Empire: The KGB in Russia Today. Westview Press. Boulder, CO, 1994. ISBN 0-8133-2323-1.

- ↑ George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-822862-7. p. 114.

- ↑ Graf Huyn, Hans (1984). "Webs of Soviet Disinformation". Strategic Review. 21 (4): 52.

- ↑ Pacepa, Ion Mihail; Rychlak, Ronald (2013). Disinformation: Former Spy Chief Reveals Secret Strategies for Undermining Freedom, Attacking Religion, and Promoting Terrorism. WND Books. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-1-93648-860-5.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984, p. 231.

- ↑ "Love and hate for 'Iron Felix': Why do Russians still debate the Soviet security services' founder?". Russia Beyond. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

Apart from that, the top Chekist supervised the establishment of a system of orphanages and child communes, which helped to solve the problem of child homelessness, which was very acute after the Civil War.

- ↑ A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Edited by Silvio Pons and Robert Service. Princeton University Press. 2010.

- ↑ "Leon Trotsky: The History of the Russian Revolution (1.16 Rearming the Party)". Marxists.org. 21 February 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ Blobaum 1984. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Isaac Deutscher. The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky 1921–1929. Oxford University Press, 1959, ISBN 1-85984-446-4. p. 279.

- ↑ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2003). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 76. ISBN 1842127268.

- ↑ Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Rada renamed Kirovograd, Ukrayinska Pravda (14 July 2016) - ↑ Decommunisation continues: Rada renames several towns and villages, UNIAN (4 February 2016)

"Rada de-communized Artemivsk as well as over hundred cities and villages" (in Ukrainian). Pravda.com.ua. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

Рада перейменувала Дніпродзержинськ на Кам'янське (in Ukrainian). Українські Національні Новини. 19 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016. - ↑ Fricke, Oscar (April 1979). "The Dzerzhinsky Commune: Birth of the Soviet 35mm Camera Industry". History of Photography. 3 (2): 135–155. doi:10.1080/03087298.1979.10441091.

- 1 2 Jabłoński, Rafał (26 November 2009). "Utracony nos czekisty". Życie Warszawy (in Polish). Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Дзержинскому еще раз отказали в месте на Лубянке". BBC. 11 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "Опрос: 45% россиян хотят вернуть памятник Дзержинскому". BBC. 5 December 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "Центральный дом художника (ЦДХ)". 24 November 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018.

- ↑ "Russia Plans To Restore Toppled 'Iron Felix' Statue". Ipotnews. 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Прокуратура признала незаконным снос памятника Дзержинскому на Лубянке". 26 April 2021.

- ↑ "Statue of founder of Soviet secret police unveiled in Moscow". theguardian.com. 11 September 2023.

- ↑ "Belarus: monument to founder of Soviet secret police unveiled in Minsk". Pravda. 26 May 2006.

- ↑ "In Ryazan, a monument to Dzerzhinsky was opened". (a)news. 11 September 2017.

- ↑ Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (6 November 2012). Intermarium: The Land between the Black and Baltic Seas. Transaction Publishers. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-4128-4786-5.

Further reading

- Blobaum, Robert. Felix Dzerzhinsky and the SDKPiL: A study of the origins of Polish Communism. 1984. ISBN 0-88033-046-5.

- Debo, Richard K. "Lockhart Plot or Dzerhinskii Plot?." Journal of Modern History 43.3 (1971): 413–439.

External links

Media related to Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky at Wikimedia Commons- Picture of the Felix calculator

- FED history Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Felix Dzerzhinsky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW