| Far-sightedness | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypermetropia, hyperopia, longsightedness, long-sightedness[1] |

| |

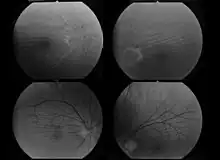

| Far-sightedness without (top) and with lens correction (bottom) | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology, optometry |

| Symptoms | Near blur, Distance and near blur, Asthenopia[2] |

| Complications | Accommodative dysfunction, binocular dysfunction, amblyopia, strabismus[3] |

| Causes | Axial length of eyeball is too short, lens or cornea is flatter than normal, aphakia[2] |

| Risk factors | Ageing, hereditary[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Eye exam |

| Differential diagnosis | Amblyopia, retrobulbar optic neuropathy, retinitis pigmentosa sine pigmento[4] |

| Treatment | Eyeglasses, contact lenses, refractive surgeries, IOL implantation[2] |

| Frequency | ~7.5% (US)[5] |

Far-sightedness, also known as long-sightedness, hypermetropia, and hyperopia, is a condition of the eye where distant objects are seen clearly but near objects appear blurred. This blur is due to incoming light being focused behind, instead of on, the retina due to insufficient accommodation by the lens.[6] Minor hypermetropia in young patients is usually corrected by their accommodation, without any defects in vision.[2] But, due to this accommodative effort for distant vision, people may complain of eye strain during prolonged reading.[2][7] If the hypermetropia is high, there will be defective vision for both distance and near.[2] People may also experience accommodative dysfunction, binocular dysfunction, amblyopia, and strabismus.[3] Newborns are almost invariably hypermetropic, but it gradually decreases as the newborn gets older.[6]

There are many causes for this condition. It may occur when the axial length of eyeball is too short or if the lens or cornea is flatter than normal.[2] Changes in refractive index of lens, alterations in position of the lens or absence of lens are the other main causes.[2] Risk factors include a family history of the condition, diabetes, certain medications, and tumors around the eye.[5][4] It is a type of refractive error.[5] Diagnosis is based on an eye exam.[5]

Management can occur with eyeglasses, contact lenses, or refractive corneal surgeries.[2] Glasses are easiest while contact lenses can provide a wider field of vision.[2] Surgery works by changing the shape of the cornea.[5] Far-sightedness primarily affects young children, with rates of 8% at 6 years old and 1% at 15 years old.[8] It then becomes more common again after the age of 40, known as presbyopia, affecting about half of people.[4] The best treatment option to correct hypermetropia due to aphakia is IOL implantation.[2]

Other common types of refractive errors are near-sightedness, astigmatism, and presbyopia.[9]

Signs and symptoms

In young patients, mild hypermetropia may not produce any symptoms.[2] The signs and symptoms of far-sightedness include blurry vision, frontal or fronto temporal headaches, eye strain, tiredness of eyes etc.[2] The common symptom is eye strain. Difficulty seeing with both eyes (binocular vision) may occur, as well as difficulty with depth perception.[1] The asthenopic symptoms and near blur are usually seen after close work, especially in the evening or night.[6]

Complications

Far-sightedness can have rare complications such as strabismus and amblyopia. At a young age, severe far-sightedness can cause the child to have double vision as a result of "over-focusing".[10]

Hypermetropic patients with short axial length are at higher risk of developing primary angle closure glaucoma, so, routine gonioscopy and glaucoma evaluation is recommended for all hypermetropic adults.[11]

Causes

Simple hypermetropia, the most common form of hypermetropia, is caused by normal biological variations in the development of eyeball.[2] Aetiologically, causes of hypermetropia can be classified as:

- Axial: Axial hypermetropia occur when the axial length of eyeball is too short. About 1 mm decrease in axial length cause 3 diopters of hypermetropia.[2] One condition that cause axial hypermetropia is nanophthalmos.[11]

- Curvatural: Curvatural hypermetropia occur when curvature of lens or cornea is flatter than normal. About 1 mm increase in radius of curvature results in 6 diopters of hypermetropia.[2] Cornea is flatter in microcornea and cornea plana.[11]

- Index: Age related changes in refractive index (cortical sclerosis) can cause hypermetropia. Another cause of index hypermetropia is diabetes.[2] Occasionally, mild hypermetropic shift may be seen in association with cortical or subcapsular cataract also.[11]

- Positional: Positional hypermetropia occur due to posterior dislocation of Lens or IOL.[2] It may occur due to trauma.

- Consecutive: Consecutive hypermetropia occur due to surgical over correction of myopia or surgical under correction in cataract surgery.[2]

- Functional: Functional hypermetropia results from paralysis of accommodation as seen in internal ophthalmoplegia, CN III palsy etc.[2]

- Absence of lens: Congenital or acquired aphakia cause high degree hypermetropia.[12]

Far-sightedness is often present from birth, but children have a very flexible eye lens, which helps to compensate.[13] In rare instances hyperopia can be due to diabetes, and problems with the blood vessels in the retina.[1]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of far-sightedness is made by utilizing either a retinoscope or an automated refractor-objective refraction; or trial lenses in a trial frame or a phoropter to obtain a subjective examination. Ancillary tests for abnormal structures and physiology can be made via a slit lamp test, which examines the cornea, conjunctiva, anterior chamber, and iris.[14][15]

In severe cases of hyperopia from birth, the brain has difficulty in merging the images that each individual eye sees. This is because the images the brain receives from each eye are always blurred. A child with severe hyperopia can never see objects in detail. If the brain never learns to see objects in detail, then there is a high chance of one eye becoming dominant. The result is that the brain will block the impulses of the non-dominant eye. In contrast, the child with myopia can see objects close to the eye in detail and does learn at an early age to see objects in detail.

Classification

Hyperopia is typically classified according to clinical appearance, its severity, or how it relates to the eye's accommodative status.

Clinical classification

There are three clinical categories of hyperopia.[3]

- Simple hyperopia: Occurs naturally due to biological diversity.

- Pathological hyperopia: Caused by disease, trauma, or abnormal development.

- Functional hyperopia: Caused by paralysis that interferes eye's ability to accommodate.

Classification according to severity

There are also three categories severity:[3]

- Low: Refractive error less than or equal to +2.00 diopters (D).

- Moderate: Refractive error greater than +2.00 D up to +5.00 D.

- High: Refractive error greater than +5.00 D.

Components of hypermetropia

Accommodation has significant role in hyperopia. Considering accommodative status, hyperopia can be classified as:[7][2]

- Total hypermetropia: It is the total amount of hyperopia which is obtained after complete relaxation of accommodation using cycloplegics like atropine.

- Latent hyperopia: It is the amount of hyperopia normally corrected by ciliary tone (approximately 1 diopter).

- Manifest hyperopia: It is the amount of hyperopia not corrected by ciliary tone. Manifest hyperopia is further classified into two, facultative and absolute.

- Facultative hyperopia: It is the part of hyperopia corrected by patient's accommodation.

- Absolute hyperopia: It is the residual part of hyperopia which causes blurring of vision for distance.

So, Total hyperopia= latent hyperopia + manifest hyperopia (facultative + absolute)[7]

Treatment

Corrective lenses

The simplest form of treatment for far-sightedness is the use of corrective lenses, i.e. eyeglasses or contact lenses.[16][17] Eyeglasses used to correct far-sightedness have convex lenses.[18]

Surgery

There are also surgical treatments for far-sightedness:

Laser procedures

- Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK): This is a refractive technique that is done by removal of a minimal amount of the corneal surface.[18][19] Hyperopic PRK has many complications like regression effect, astigmatism due to epithelial healing, and corneal haze.[20] Post operative epithelial healing time is also more for PRK.[21]

- Laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK): Laser eye surgery to reshape the cornea, so that glasses or contact lenses are no longer needed.[19][22] Excimer laser LASIK can correct hypermetropia up to +6 diopters.[20] LASIK is contraindicated in patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.[20]

- Laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK): Resembles PRK, but uses alcohol to loosen the corneal surface.[18]

- Epi-LASIK: Epi-LASIK is also used to correct hyperopia.[21] In this procedure, use of epikeratome eliminates the use of alcohol.[21]

- Laser thermal keratoplasty (LTK): Laser thermal keratoplasty is a laser based non-destructive refractive procedure used to correct hyperopia and presbyopia.[21] It uses Thallium-Holmium-Chromium (THC): YAG laser.[21]

IOL implantation

- Aphakia correction: High degree hypermetropia due to absence of lens (aphakia) is best corrected using intraocular lens implantation.

- Refractive lens exchange (RLE): A variation of cataract surgery where the natural crystalline lens is replaced with an artificial intraocular lens; the difference is the existence of abnormal ocular anatomy which causes a high refractive error.[23]

- Phakic IOL: Phakic intraocular lens are lenses that implanted inside eye without removing the normal crystalline lens. Phakic IOLs can be used to correct hypermetropia up to +20 diopters.[21]

Non laser procedures

- Conductive keratoplasty (CK): Conductive keratoplasty is a non laser refractive procedure used to correct presbyopia and low hypermetropia (+0.75D to +3.25D) with or without astigmatism (up to 0.75D).[21][24] It uses radiofrequency energy to heat and shrink corneal collagen tissue. CK is contraindicated in pregnant/breastfeeding women, central corneal dystrophies and scarring, history of herpetic keratitis, type 1 diabetes etc.[24]

- Automated lamellar keratoplasty (ALK): Hyperopic automated lamellar keratoplasty (H-ALK) and Homoplastic ALK are ALK procedures that corrects low to moderate hyperopia.[25] Poor predictability and the risk of complications limits usefulness of these procedures.[25]

- Keratophakia and epi-keratophakia are another two non laser surgical procedures used to correct hypermetropia.[25] Keratophakia is a surgical technique developed by Barraquer for treating high hypermetropia and aphakia. Poor predictability and induced irregular astigmatism are complications of these procedures.[25]

Etymology

The term hyperopia comes from Greek ὑπέρ hyper "over" and ὤψ ōps "sight" (GEN ὠπός ōpos).[26]

References

- 1 2 3 Lowth, Mary. "Long Sight (Hypermetropia)". Patient. Patient Platform Limited. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Khurana, AK (September 2008). "Errors of refraction and binocular optical defects". Theory and practice of optics and refraction (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 62–66. ISBN 978-81-312-1132-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, Bruce D.; Augsburger, Arol R.; Ciner, Elise B.; Cockrell, David A.; Fern, Karen D.; Harb, Elise (2008). "Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Hyperopia" (PDF). American Optometric Association. pp. 2–3, 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- 1 2 3 Kaiser, Peter K.; Friedman, Neil J.; II, Roberto Pineda (2014). The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 541. ISBN 9780323225274. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Facts About Hyperopia". NEI. July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ramjit, Sihota; Radhika, Tandon (15 July 2015). "Refractive errors of the eye". Parsons' diseases of the eye (22nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-81-312-3818-9.

- 1 2 3 Pablo, Artal (2017). Handbook of visual optics-Fundamentals and eye optics and. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-3785-6.

- ↑ Castagno, VD; Fassa, AG; Carret, ML; Vilela, MA; Meucci, RD (23 December 2014). "Hyperopia: a meta-analysis of prevalence and a review of associated factors among school-aged children". BMC Ophthalmology. 14: 163. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-14-163. PMC 4391667. PMID 25539893.

- ↑ "Facts About Refractive Errors". National Eye Institute. October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "Complications of long-sightedness". NHS Choices. National Health Service. 2014-07-09. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 4 John F., Salmon (2020). Kanski's clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach (9th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7713-5. OCLC 1131846767.

- ↑ Khurana, AK (2015). "Errors of refraction and accommodation". Comprehensive ophthalmology (6th ed.). Jaypee, The Health Sciences Publisher. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-93-86056-59-7.

- ↑ "Normal, near-sightedness, and far-sightedness". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Farsightedness". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Slit-lamp exam". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Chou, Roger; Dana, Tracy; Bougatsos, Christina (2011-02-01). "Introduction". Screening for Visual Impairment in Children Ages 1-5 Years: Systematic Review to Update the 2004 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation (Report). Evidence Syntheses. Vol. 81. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08 – via PubMed Health.

- ↑ "Farsightedness (Hyperopia): Treatments". PubMed Health. U. S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 "Treating long-sightedness". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 Settas, George; Settas, Clare; Minos, Evangelos; Yeung, Ian Yl (2012-01-01). "Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) versus laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) for hyperopia correction". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD007112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007112.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7388917. PMID 22696365.

- 1 2 3 Gulani, Arun C (9 November 2019). "LASIK Hyperopia: Background, History of the Procedure, Problem".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Khurana, AK (September 2008). "Refractive surgery". Theory and practice of optics and refraction (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 307–348. ISBN 978-81-312-1132-8.

- ↑ "Laser Eye Surgery". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Alió, Jorge L.; Grzybowski, Andrzej; Romaniuk, Dorota (2014-12-10). "Refractive lens exchange in modern practice: when and when not to do it?". Eye and Vision. 1: 10. doi:10.1186/s40662-014-0010-2. ISSN 2326-0254. PMC 4655463. PMID 26605356.

- 1 2 "Conductive Keratoplasty". eyewiki.aao.org.

- 1 2 3 4 Refractive surgery. Azar, Dimitri T. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby / Elsevier. 2007. ISBN 978-0-323-03599-6. OCLC 853286620.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "hyperopia". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.