Factory was the common name during the medieval and early modern eras for an entrepôt – which was essentially an early form of free-trade zone or transshipment point. At a factory, local inhabitants could interact with foreign merchants, often known as factors.[1] First established in Europe, factories eventually spread to many other parts of the world. The origin of the word factory is from Latin factorium 'place of doers, makers' (Portuguese: feitoria; Dutch: factorij; French: factorerie, comptoir).

The factories established by European states in Africa, Asia and the Americas from the 15th century onward also tended to be official political dependencies of those states. These have been seen, in retrospect, as the precursors of colonial expansion.

A factory could serve simultaneously as market, warehouse, customs, defense and support to navigation and exploration, headquarters or de facto government of local communities.

In North America, Europeans began to trade with Natives during the 16th century. Colonists created factories, also known as trading posts, at which furs could be traded, in Native American territory.

European medieval factories

Although European colonialism traces its roots from the classical era, when Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans established colonies of settlement around the Mediterranean – "factories" were a unique institution born in medieval Europe.

Originally, factories were organizations of European merchants from a state, meeting in a foreign place. These organizations sought to defend their common interests, mainly economic (as well as organized insurance and protection), enabling the maintenance of diplomatic and trade relations within the foreign state where they were set.

The factories were established from 1356 onwards in the main trading centers, usually ports or central hubs that have prospered under the influence of the Hanseatic League and its guilds and kontors. The Hanseatic cities had their own law system and furnished their own protection and mutual aid. The Hanseatic League maintained factories, among others, in England (Boston, King's Lynn), Norway (Tønsberg) and Finland (Åbo). Later, cities like Bruges and Antwerp actively tried to take over the monopoly of trade from the Hansa, inviting foreign merchants to join in.

Because foreigners were not allowed to buy land in these cities, merchants joined around factories, like the Portuguese in their Bruges factory: the factor(s) and his officers rented the housing and warehouses, arbitrated trade, and even managed insurance funds, working both as an association and an embassy, even administering justice within the merchant community.[2]

Portuguese feitorias (c. 1445)

During the territorial and economic expansion of the Age of Discovery, the factory was adapted by the Portuguese and spread throughout from West Africa to Southeast Asia.[3] The Portuguese feitorias were mostly fortified trading posts settled in coastal areas, built to centralize and thus dominate the local trade of products with the Portuguese kingdom (and thence to Europe). They served simultaneously as market, warehouse, support to the navigation and customs and were governed by a feitor ("factor") responsible for managing the trade, buying and trading products on behalf of the king and collecting taxes (usually 20%).

The first Portuguese feitoria overseas was established by Henry the Navigator in 1445 on the island of Arguin, off the coast of Mauritania. It was built to attract Muslim traders and monopolize the business in the routes traveled in North Africa. It served as a model for a chain of African feitorias, Elmina Castle being the most notorious.

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, a chain of about 50 Portuguese forts either housed or protected feitorias along the coasts of West and East Africa, the Indian Ocean, China, Japan, and South America. The main factories of the Portuguese East Indies, were in Goa, Malacca, Ormuz, Ternate, Macao, and the richest possession of Bassein that went on become the financial centre of India as Bombay (Mumbai). They were mainly driven by the trade of gold and slaves on the coast of Guinea, spices in the Indian Ocean, and sugar cane in the New World. They were also used for local triangular trade between several territories, like Goa-Macau-Nagasaki, trading products such as sugar, pepper, coconut, timber, horses, grain, feathers from exotic Indonesian birds, precious stones, silks and porcelain from the East, among many other products. In the Indian Ocean, the trade in Portuguese factories was enforced and increased by a merchant ship licensing system: the cartazes.[4]

From the feitorias, the products went to the main outpost in Goa, then to Portugal where they were traded in the Casa da Índia, which also managed exports to India.[5] There they were sold, or re-exported to the Royal Portuguese Factory in Antwerp, where they were distributed to the rest of Europe.

Easily supplied and defended by sea, the factories worked as independent colonial bases. They provided safety, both for the Portuguese, and at times for the territories in which they were built, protecting against constant rivalries and piracy. They allowed Portugal to dominate trade in the Atlantic and Indian oceans, establishing a vast empire with scarce human and territorial resources. Over time, the feitorias were sometimes licensed to private entrepreneurs, giving rise to some conflict between abusive private interests and local populations, such as in the Maldives.

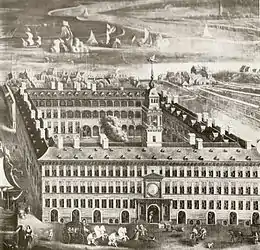

Dutch factorij and other European factories (1600s)

Other European powers began to establish factories in the 17th century along the trade routes explored by Portugal and Spain, first the Dutch and then the English. They went on to establish in conquered Portuguese feitorias and further enclaves, as they explored the coasts of Africa, Arabia, India, and South East Asia in search of the source of the lucrative spice trade.

Factories were then established by chartered companies such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), founded in 1621. These factories provided for the exchange of products among European companies, local populations, and the colonies that often started as a factory with warehouses. Usually these factories had larger warehouses to fit the products resulting from the increasing agricultural development of colonies, which were boosted in the New World by the Atlantic slave trade.

In these factories, the products were checked, weighed, and packaged to prepare for the long sea voyage. In particular, spices, cocoa, tea, tobacco, coffee, sugar, porcelain, and fur were well protected against the salty sea air and against deterioration. The factor was present as the representative of the trading partners in all matters, reporting to the headquarters and being responsible for the products’ logistics (proper storage and shipping). Information took a long time to reach the company headquarters, and this was dependent on an absolute trust.

Some Dutch factories were located in Cape Town in modern-day South Africa, Mocha in Yemen, Calicut and the Coromandel Coast in southern India, Colombo in Sri Lanka, Ambon in Indonesia, Fort Zeelandia in Taiwan, Canton in southern China, Dejima island in Japan (the only legal point of trade between Japan and the outside world during the Edo Period), and Fort Orange in modern-day Upstate New York in the United States.

North American factories (1697 to 1822)

The American factories often played a strategic role as well, sometimes operating as forts, providing a degree of protection for colonists and their allies from hostile Indians and foreign colonists.

York Factory was founded by the chartered Hudson's Bay Company in 1697. It was headquarters of the company for a long time, and was once the de facto government in parts of North America such as Rupert's Land, before European-based colonies existed. It controlled the fur trade throughout much of British-controlled North America for several centuries, undertaking early exploration. Its traders and trappers forged early relationships with many groups of American Indians, and a network of trading posts formed the nucleus for later official authority in many areas of Western Canada and the United States.

The early coastal factory model contrasted with the system of the French, who established an extensive system of inland posts and sent traders to live among the tribes of the region. When war broke out in the 1680s between France and England, the two nations regularly sent expeditions to raid and capture each other's fur trading posts. In March 1686, the French sent a raiding party under Chevalier des Troyes over 1,300 km (810 mi) to capture the company's posts along James Bay. In 1697, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, commander of the company's captured posts, defeated three ships of the Royal Navy in the Battle of the Bay on his way to capture York Factory by a ruse. York Factory changed hands several times in the next decade and was finally ceded permanently in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. After the treaty, the Hudson Bay Company rebuilt York Factory as a brick star fort at the mouth of the nearby Hayes River, its present location.

The United States government sanctioned a factory system from 1796 to 1822, with factories scattered through the mostly territorial portion of the country.

The factories were officially intended to protect Indians from exploitation through a series of legislation called the Indian Intercourse Acts. However, in practice, numerous tribes conceded extensive territory in exchange for the trading posts, as happened in the Treaty of Fort Clark in which the Osage Nation ceded most of Missouri at Fort Clark.

A blacksmith was usually assigned to the factory to repair utensils and build or maintain plows. The factories frequently also had some sort of milling operation associated with them.

The factories marked the United States' attempt to continue a process originally pioneered by the French and then by the Spanish to officially license the fur trade in Upper Louisiana.

Factories were frequently called "forts" and often had numerous unofficial names. Legislation was often passed calling for military garrisons at the fort but their de facto purpose was a trading post.

Examples

In Canada, the Hudson's Bay Company created several factories,[6] including:

- Rupert House, 1668 (now Waskaganish, Quebec)

- Moose Fort, 1673 (now Moose Factory, Ontario)

- Fort Albany, 1679 (Ontario)

- York Factory, 1684 (Manitoba)

- Fort Severn, 1685 (Ontario)

- Churchill River Post, 1717 (now Churchill, Manitoba)

In the United States factories under the Superintendent of Indian Trade:[7]

- Creek:

- Colerain, 1795–1797

- Fort Wilkinson, 1797–1806

- Ocmulgee Old Fields, 1806–1809

- Fort Hawkins, 1809–1816

- Fort Mitchell, 1816–1820

- Cherokee:

- Fort Tellico, 1795–1807

- Fort Hiwassee, 1807–1810

- Fort Wayne, 1802–1812

- Choctaw:

- Fort St. Stephens, 1802–1815

- Fort Confederation, 1816–1822

- Fort Chickasaw Bluffs, 1802–1818

- Fort Detroit, 1802–1805

- Fort Arkansas, 1805–1810

- Fort Chicago, 1805–1822

- Fort Belle Fontaine, 1805–1809

- Natchitoches—Sulphur Fork

- Fort Natchitoches, 1805–1818

- Fort Sulphur Fork, 1818–1822

- Fort Sandusky, 1806–1812

- Fort Madison, Iowa 1808–1815

- Fort Osage, 1808–1822

- Fort Mackinac (Michilimackinac), 1808–1812

- Fort Green Bay, 1815–1822

- Fort Praire du Chien, 1815–1822

- Fort Edwards, 1818–1822

- Fort Spadre Bluffs (Illinois Bayou), 1818–1822

References

- ↑ Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, Portland House, New York, 1983.

- ↑ Diogo Ramada Curto, Francisco Bethencourt, "O tempo de Vasco da Gama", DIFEL, 1998, ISBN 972-8325-47-9

- ↑ Diffie 1977, pp. 314–315

- ↑ Diffie 1977, pp. 320–322

- ↑ Diffie 1977, p. 316

- ↑ Voorhis, Ernest (1930). "Historic Forts of the French Regime and of the English Trading Companies". enhaut.ca/voor1. Government of Canada. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "Preliminary Inventory (PI 163) of the Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (RG 75), Washington, D.C. Area". 1965. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

Sources

- Braudel, Fernand (1992). Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century: The perspective of the world. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08116-1.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-131071-7.

- Tracy, James D. (1997). The political economy of merchant empires. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57464-1.

- Rau, Virginia (1965). "Feitores e feitorias - "Instrumentos" do comércio internacional português no Séc. XVI". Brotéria. 81 (nº 5).

- Diffie, Bailey (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6.

External links

- Wisconsinhistory.org definition Archived 2017-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Chicago History