| Facial motor nucleus | |

|---|---|

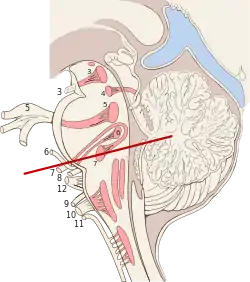

Plan of the facial and intermediate nerves and their communication with other nerves. ("Nucleus of Facial N." labeled at upper left.) | |

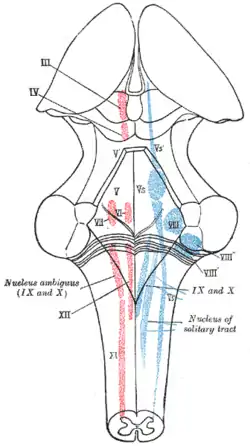

Diagram of brain stem showing the nuclei of the cranial nerves | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Medulla oblongata |

| Artery | AICA |

| Vein | Anterior medullary |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Nucleus nervi facialis |

| MeSH | D065828 |

| NeuroNames | 586 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_903 |

| TA98 | A14.1.05.412 |

| TA2 | 5939 |

| FMA | 54572 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The facial motor nucleus is a collection of neurons in the brainstem that belong to the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII).[1] These lower motor neurons innervate the muscles of facial expression and the stapedius.[2]

Structure

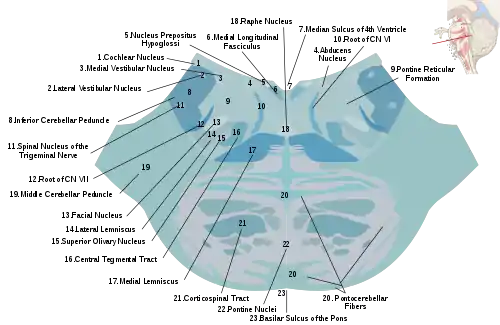

The nucleus is situated in the caudal portion of the ventrolateral pontine tegmentum. Its axons take an unusual course, traveling dorsally and looping around the abducens nucleus, then traveling ventrally to exit the ventral pons medial to the spinal trigeminal nucleus. These axons form the motor component of the facial nerve, with parasympathetic and sensory components forming the intermediate nerve.

The nucleus has a dorsal and ventral region, with neurons in the dorsal region innervating muscles of the upper face and neurons in the ventral region innervating muscles of the lower face.

Function

Because it innervates muscles derived from pharyngeal arches, the facial motor nucleus is considered part of the special visceral efferent (SVE) cell column, which also includes the trigeminal motor nucleus, nucleus ambiguus, and (arguably) the spinal accessory nucleus.

Cortical input

Like all lower motor neurons, cells of the facial motor nucleus receive cortical input from the primary motor cortex in the frontal lobe of the brain. Upper motor neurons of the cortex send axons that descend through the internal capsule and synapse on neurons in the facial motor nucleus. This pathway from the cortex to the brainstem is called the corticobulbar tract.

The neurons in the dorsal aspect of the facial motor nucleus receive inputs from both sides of the cortex, while those in the ventral aspect mainly receive contralateral inputs (i.e. from the opposite side of the cortex). The result is that both sides of the brain control the muscles of the upper face, while the right side of the brain controls the lower left side of the face, and the left side of the brain controls the lower right side of the face.

Clinical significance

As a result of the corticobulbar input to the facial motor nucleus, an upper motor neuron lesion to fibers innervating the facial motor nucleus results in central seven. The syndrome is characterized by spastic paralysis of the contralateral lower face. For example, a left corticobulbar lesion results in paralysis of the muscles that control the lower right quadrant of the face.

By contrast, a lower motor neuron lesion to the facial motor nucleus results in paralysis of facial muscles on the same side of the injury. If a cause, such as trauma or infection, cannot be identified (this situation is called idiopathic palsy) this condition is known as Bell's palsy. Otherwise it is described by its cause.

Mechanism of Facial Nerve Upper vs Lower Motor Neuron Lesions

Any lesion occurring within or affecting the corticobulbar tract is known as an upper motor neuron lesion. Any lesion affecting the individual branches (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical) is known as a lower motor neuron lesion.

Branches of the facial nerve leaving the facial motor nucleus (FMN) for the muscles do so via both left and right posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) routes. In other words, this means lower motor neurons of the facial nerve can leave either from the left anterior, left posterior, right anterior or right posterior facial motor nucleus. The temporal branch travels out from the left and right posterior components. The inferior four branches do so via the left and right anterior components. The left and right branches supply their respective sides of the face (ipsilateral innervation). Accordingly, the posterior components receive motor input from both hemispheres of the cerebral cortex (bilaterally), whereas the anterior components receive strictly contralateral input. This means that the temporal branch of the facial nerve receives motor input from both hemispheres of the cerebral cortex whereas the zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical branches receive information from only contralateral hemispheres.

Now, because the anterior FMN receives only contralateral cortical input whereas the posterior receives that which is bilateral, a corticobulbar lesion (UMN lesion) occurring in the left hemisphere would eliminate motor input to the right anterior FMN component, thus removing signaling to the inferior four facial nerve branches, thereby paralyzing the right mid- and lower-face. The posterior component, however, although now only receiving input from the right hemisphere, is still able to allow the temporal branch to sufficiently innervate the entire forehead. This means that the forehead will not be paralyzed.

The same mechanism applies for an upper motor neuron lesion in the right hemisphere. The left anterior FMN component no longer receives cortical motor input due to its strict contralateral innervation, whereas the posterior component is still sufficiently supplied by the left hemisphere. The result is paralysis of the left mid- and lower-face with an unaffected forehead.

On the other hand, a lower motor neuron lesion is a bit different.

A lesion on either the left or right side would affect both the anterior and posterior routes on that side because of their close physical proximity to one another. So, a lesion on the left side would inhibit muscle innervation from both the left posterior and anterior routes, thus paralyzing the whole left side of the face (Bell’s palsy). With this type of lesion, the bilateral and contralateral inputs of the posterior and anterior routes, respectively, become irrelevant because the lesion is below the level of the medulla and the facial motor nucleus. Whereas at a level above the medulla a lesion occurring in one hemisphere would mean that the other hemisphere could still sufficiently innervate the posterior facial motor nucleus, a lesion affecting a lower motor neuron would eliminate innervation altogether because the nerves no longer have a means to receive compensatory contralateral input at a downstream decussation.

Thus, the main distinction between an UMN and LMN lesion is that in the former, there is hemiplegia of the contralateral mid- and lower-face, whereas in the latter, there is complete hemiplegia of the ipsilateral face.

Additional images

The cranial nerve nuclei schematically represented; dorsal view. Motor nuclei in red; sensory in blue.

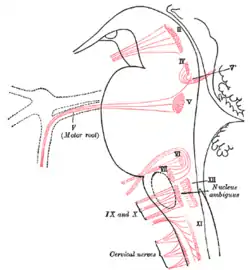

The cranial nerve nuclei schematically represented; dorsal view. Motor nuclei in red; sensory in blue. Nuclei of origin of cranial motor nerves schematically represented; lateral view.

Nuclei of origin of cranial motor nerves schematically represented; lateral view. Cross section of the lower pons showing the facial motor nucleus and part of the root of the facial nerve.

Cross section of the lower pons showing the facial motor nucleus and part of the root of the facial nerve.

References

- ↑ Sherwood, Chet C. (2 October 2005). "Comparative anatomy of the facial motor nucleus in mammals, with an analysis of neuron numbers in primates". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 287A (1): 1067–1079. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20259. ISSN 1552-4884. PMID 16200649. S2CID 17331516.

- ↑ Rouiller, Eric M.; Capt, Mauricette; Dolivo, Michel; De Ribaupierre, Francois (1989-01-02). "Neuronal organization of the stapedius reflex pathways in the rat: a retrograde HRP and viral transneuronal tracing study". Brain Research. 476 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(89)91532-1. ISSN 0006-8993. PMID 2464420. S2CID 19371444.