Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) are insects with an incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolous). The aquatic larva or nymph hatches from an egg, and develops through eight to seventeen instars before leaving the water and emerging as the winged adult or imago.[1]

Imago

The imago (adult stage) has a large head, well-developed, compound eyes, legs that facilitate catching prey (largely other insects) in flight, two pairs of long, transparent wings that move independently, and an elongated abdomen.[2]

Many Odonata are relatively large insects, but wingspans range from 17 mm (some Agriocnemis damselflies) to 191 mm (helicopter damselfly Megaloprepus coerulatus. The largest dragonflies have a wingspan of up to 160 mm, but they are much more massive than any damselfly.[1]

Head

The globular compound eyes each have up to 28000 ommatidia and provide sharp color vision; On the forehead there are three ocelli, which can distinguish light from dark, and help with orientation in flight. The two short antennae are tactile receptors. The mouthparts are on the underside of the head and include simple chewing mandibles.[1]

_(1917)_(20388381761).jpg.webp)

Thorax

The front segment of the thorax (prothorax) carries a pair of legs, and the synthorax carries the middle and rear legs and both pairs of wings. A dark stripe (humeral stripe) often follows the humeral suture, which runs from the base of the front wing towards the base of the middle leg. A paler antehumeral stripe is often found above the humeral stripe.

Wings

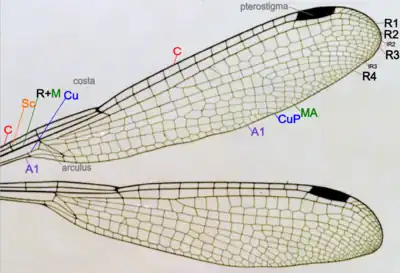

The wings have a network of veins; between the veins the wings are generally transparent, but may be partly colored.[1] In most Odonata there is a structure on the leading edge near the tip of the wing called the pterostigma. This is a thickened, hemolymph–filled and often colorful area bounded by veins. The functions of the pterostigma are not fully known, but it most probably has an aerodynamic effect[4] and may also have a visual function. More mass at the end of the wing may also reduce the energy needed to move the wings up and down. The right combination of wing stiffness and wing mass could reduce the energy consumption of flying.

There are five main vein stems on dragonfly and damselfly wings, and wing veins are fused at their bases. The main veins are:

- Costa (C) – at the leading edge of the wing, strong and marginal, extends to the apex of the wing.

- Subcosta (Sc) – second longitudinal vein, it is unbranched and joins the costa at the nodus.

- Radius and Media (R+M) – third and fourth longitudinal veins, the strongest vein on the wing, with branches R1 to R4 reaching the wing margin; the media anterior (MA) also reaches the wing margin. IR2 and IR3 are intercalary veins behind R2 and R3 respectively.

- Cubitus (Cu) – the fifth longitudinal vein, cubitus posterior (CuP) is unbranched and reaches the wing margin.

- Anal veins (A1) – unbranched veins behind the cubitus.

A nodus is formed where the subcostal vein meets the leading edge of the wing. The dark pterostigma is carried near the wing tip.

The main veins and the crossveins form the wing venation pattern. The venation patterns are different in different species and can be useful for species identification.[5]

Legs

The legs are used for the capture and handling of prey, for grasping females, for repelling rivals, and for clinging while perching; they have long spines on the femur and tibia.[1]

Abdomen

The abdomen is long and cylindrical in many species, but in the Libellulidae it may be relatively short and broad. It has ten segments (S1-S10), terminating with appendages on S10. Males have both upper appendages (cerci) and lower appendages (epiprocts in dragonflies and paraprocts in damselflies), which are used to hold females while mating; these are also termed claspers. Males also have secondary genitalia (including the anterior lamina, hamuli and posterior lamina) on S2 and S3. Female damselflies and some dragonflies have a strong ovipositor on the underside of S8 and S9, but in many dragonflies the egg-laying apparatus is merely a spout, a basket, or a pair of flaps. Some species have foliations (leaf-like extensions) on S8 and/or S9.

Nymph

The aquatic nymph (larva) has a stockier, shorter, body than the adult. It lacks wings, the eyes are smaller, the antennae longer, and the head is less mobile than in the adult. The mouthparts are modified, with the labium being adapted into a unique prehensile organ for grasping prey. Damselfly nymphs breathe through external gills on the abdomen, while dragonfly nymphs respire through an organ in their rectum.[2]

Differences between dragonflies and damselflies

Although generally fairly similar, dragonflies differ from damselflies in several, easily recognizable traits. Dragonflies are strong fliers with fairly robust bodies and they have wings that are broad near the base; at rest the wings are held out to the side. Damselflies tend to be less robust, and appear weaker in flight; their wings are narrow near the base and (in most species) held folded back over the abdomen when perched. Dragonfly eyes occupy much of the animal's head, touching (or nearly touching) each other across the face. In damselflies, there is typically a gap in between the eyes.

See also

- Insect morphology

- Insect physiology

- Insect ecology

- Insect flight

- Entomology

- Prehistoric insect

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Suhling, F.; Sahlén, G.; Gorb, S.; Kalkman, V.J.; Dijkstra, K-D.B.; van Tol, J. (2015). "Order Odonata". In Thorp, J.; Rogers, D.C. (eds.). Ecology and General Biology: Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates (4th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 893–932. ISBN 9780123850263.

- 1 2 Hoell, H.V., Doyen, J.T. & Purcell, A.H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. pp. 355–358. ISBN 0-19-510033-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Tillyard, R.J. (1917). The Biology of Dragonflies (Odonata or Paraneuroptera). Cambridge: University Press. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ Norberg, R. Åke (1972). "The pterostigma of insect wings an inertial regulator of wing pitch". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 81 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1007/BF00693547. S2CID 198144535.

- ↑ Chew, Peter (May 9, 2009). "Insect Wings". Brisbane Insects and Spiders. Retrieved 2011-03-21.