| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 88.200.000 43.4% of Brazilians identify as being white[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Entire country; highest percents found in southern states and southeast states | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese minorities speak assorted German dialects, mainly Riograndenser Hunsrückisch, Talian and Polish. Other smaller minorities include Ukrainian, Dutch, Lithuanian, Russian, Yiddish | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Agnosticism, Atheism, Spiritism, Jehovah Witnesses, Mormonism, Orthodoxy, Judaism, Buddhism and Japanese new religions |

European immigration to Brazil refers to the movement of European people to Brazil. It should not be confused with the colonisation of the country by the Portuguese.

History

Maria Stella Ferreira Levy[2] suggests the following periodisation of the process of immigration to Brazil:

- 1. 1820-1876: small number of immigrants (about 6,000 per year), predominance of Portuguese (45.73%), with significant numbers of Germans (12.97%);

- 2. 1877-1903: large number of immigrants (about 71,000 per year), predominance of Italians (58.49%);

- 3. 1904-1930: large number of immigrants (about 79,000 per year), predominance of the Portuguese (36.97%);

- 4. 1931-1963: declining number of immigrants (about 33,500 per year), predominance of the Portuguese (38.45%).

During the first two periods, immigration to Brazil was almost exclusively of European origin, and it remained the majority during all four, in spite of the increasing importance of Japanese immigration.

First period: 1820-1872

Immigration properly started with the opening of the Brazilian ports, in 1808. The government began to stimulate the arrival of Europeans to occupy plots of land and become small farmers. After independence from Portugal, the Brazilian Empire focused on the occupation of the provinces of Southern Brazil.[3] From 1824, immigrants from Central Europe started to populate what is nowadays the region of São Leopoldo, in the province of Rio Grande do Sul. Immigration stalled in 1830, due to legislation forbidding government spending with the settlement of immigrants. Besides, Rio Grande do Sul, the main target of immigration, was convulsed with civil war from 1835 to 1845.[4]

Between 1820 and 1871, 350,117 immigrants entered Brazil. Of these, 45.73% were Portuguese, 35.74% of "other nationalities," 12.97% Germans, while Italians and Spanish together did not reach 6%. The total number of immigrants per year averaged 6,000.[5] Portuguese immigrants generally were sought after for the cities as they were established in commerce and peddling; others, particularly the Germans, were brought to settle in rural communities as small landowners. They received land, seed, livestock and other items to develop.

Second Period: 1872-1903

In the last quarter of the 19th century, the entry of immigrants in Brazil grew strongly. On one hand, Europe underwent a serious demographic crisis, which resulted in increased immigration; on the other hand, the final crisis of Brazilian slavery prompted Brazilian authorities to find solutions for the problem of work force. Consequently, while immigration until 1872 was focused on establishing communities of landowners, during this period, while this older process continued, immigrants were more and more attracted to the coffee plantations of São Paulo, where they became employees or were allowed to cultivate small tracts of land in exchange for their work in the coffee crop.[3]

During this period, immigration was much more intense: large numbers of Europeans, especially Italians, 1.1 million (of a total of almost 2 million from 1870 to 1940), were brought to the country to work in the harvest of coffee, their travel being paid by Brazilian government.[6] 1872 to 1903, almost two million immigrants arrived, at a rate of 71,000 per year[7]

By the beginning of the 1870s, the alternative of the interprovincial slave trade was exhausted, while the demand for workforce in the coffee plantations continued to expand. Thus the paulista oligarchy sought to attract new workers from abroad, by passing provincial legislation and pressuring the Brazilian government to organise immigration.[8][9] Tensions arose between the governmental bureaucracy, that was concerned in populating the country with immigrants deemed easily adaptable to Brazilian culture and compatible with the racial prejudices of the time, and the coffee planters, eager for cheap labour force of whatever origin; government concerns predominated while Italian and Spanish immigration was sufficient to meet the demand, but as early as 1892 pressure from the planters forced the government to abandon restrictions against Asian immigrants, although a serious crisis in the coffee culture by the end of the century postponed any practical initiatives concerning this until 1908.

Third period: 1904-1930

From 1904 to 1930, 2,142,781 immigrants came to Brazil - making an annual average of 79,000 people. In consequence of the Prinetti Decree of 1902, that forbade subsidised emigration to Brazil, Italian immigration had, at this stage, a drastic reduction: their average annual entries from 1887 to 1903 was 58,000. In this period they were only 19,000 annually. As a consequence, immigration of non-Europeans was organised, with Japanese immigrants arriving from 1908 on. The Portuguese constituted 38% of entries, followed by Spaniards with 22% and Germans. From 1914 to 1918, due to World War I, the entry of immigrants of all nationalities decreased.[5] After the War, the immigration of people of "other nationalities" redressed faster than that of Portuguese, Spaniards, Germans and Italians. Part of this category was composed of immigrants from Poland, Russia and Romania - whose emigration was prompted by the collapse of the Russian and Austrian-Hungarian Empires in the aftermath of the First World War - but part by non-Europeans, mainly Syrian and Lebanese people. Both subgroups included a number of Jewish immigrants, who arrived in the 1920s. Overall, European immigration remained clearly majoritary during the period, though Japanese immigration grew, and attempts to restrict immigration to Europeans, on racist bases, in 1921 and 1923, were defeated in the Brazilian Congress; however, attempts to organise Black American immigration to Brazil also failed due to administrative action by the Brazilian consulates in the United States, that systematically denied visa to Black applicants, on confidential orders by the Brazilian Foreign Affairs Ministry.[10]

Fourth Period: 1931-1964

From 1931 to 1963, 1,106,404 immigrants entered Brazil, at an annual rate of 33,500. The participation of Europeans decreased, while that of Japanese increased. From 1932 to 1935 immigrants from Japan constituted 30% of total admissions.[5]

With the radicalisation of the political situation in Europe, the end of the demographic crisis, the decadence of coffee culture, the Revolution of 1930 and the consequent rise of a nationalist government, immigration to Brazil was significantly reduced. The Portuguese remained the most significant group, with 39.35%.[5]

Immigration also became a more urban phenomenon; most immigrants came for the cities, and even the descendants of the immigrants of the previous periods were moving intensely from the countryside. In the 1950s, Brazil started a program of immigration to provide workers for Brazilian industries. In São Paulo, for example, between 1957 and 1961, more than 30% of the Spanish, over 50% of the Italian and 70% of the Greek immigrants were brought to work in factories.

The role of European immigration in the transition from slave labour to wage labour

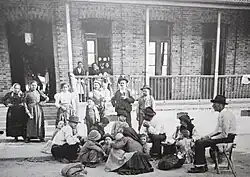

.jpg.webp)

There seems to be no easy explanation of why slaves were not employed as wage workers at the abolition of slavery. One possibility is the influence of race-based ideas from the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century, which were based in the pseudo-scientific belief of the superiority of the "White race". On the other hand, Brazilian latifundiaries had been using slave manpower for centuries, with no complaints about the quality of this workforce, and there were not important changes in Brazilian economy or work processes that could justify such sudden preoccupation with the "race" of the labourers. Their embracing of those new, racist, ideas, moreover, proved quite flexible, even opportunist: with the slow down of Italian immigration since 1902 and the Prinetti Decree, Japanese immigration started in 1908, with any qualms about their non-Whiteness being quickly forgotten.

An important, and usually ignored, part of this equation was the political situation in Brazil, during the final crisis of slavery. According to Petrônio Domingues, by 1887 the slave struggles pointed to a real possibility of widespread insurrection. It was as a response to such situation that, on May 13, 1888, slavery was abolished, as a means to restore order and the control of the ruling class, in a situation in which the slave system was almost completely disorganised.

Another factor, also usually neglected, is the fact that, regardless of the racial notions of the Brazilian elite, European populations were emigrating in great numbers - to the United States, to Argentina, to Uruguay - which African populations certainly weren't doing, at that time. In this respect, what was new in "immigration to Brazil" was not the "immigration", but the "to Brazil" part. As Wilson do Nascimento Barbosa puts it,

- The collapse of slavery was the economic result of three conjugated movements: a) the end of the first industrial revolution (1760-1840) and the beginning of the so-called second industrial revolution (1880-1920); b) the lowering of the reproduction costs of the White man in Europe (1760-1860), due to the sanitary and pharmacological impact of the first industrial revolution; c) the raising costs of African Black slaves, due to the increasing reproduction costs of Black men in Africa.

Slavery was abolished by law (Lei Áurea, signed by Regent Princess Isabel) on 13 May 1888.[11]

The influence of racist pseudo-scientific ideologies, then prevalent among the educated elites in the Western World, may have caused the Brazilian government to believe that the Brazilian national identity could only be built in the base of European immigration. However, other factors were possibly at work here, such as the necessity of bringing permanent immigrants (avoiding a phenomenon similar to the golondrina migration to Argentina was certainly a concern), implying the necessity of bringing immigrant families instead of lone individuals, and considerations about language, religion, and other cultural issues. Nevertheless, these government positions were never unopposed among the ruling landed class, which often pressed for a more lax policy on immigration, particularly when there was labour shortage.

The Lei Áurea set off a reaction among slave owners, which contributed to the erosion of the political foundations of the monarchy. After a few months of parliamentary crises, the Emperor was deposed by the military on November 15, 1889, and a Republican government established.

References

- ↑ "Censo Demográfi co 2010 Características da população e dos domicílios Resultados do universo" (PDF). 8 November 2011. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ↑ http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v8s0/03.pdf Maria Stella Ferreira Levy. O papel da migração internacional na evolução da população brasileira (1872 a 1972) p. 52.

- 1 2 O papel da migração internacional na evolução da população brasileira (1872 a 1972)

- ↑ Maria Stella Ferreira Levy. O papel da migração internacional na evolução da população brasileira (1872 a 1972) p.51.

- 1 2 3 4 Entrada de estrangeiros no Brasil

- ↑ Eliane Yambanis Obersteiner. Café atrai imigrante europeu para o Brasil - 22 February 2005 - Resumos | História do Brasil

- ↑ Maria Stella Ferreira Levy . p.51

- ↑ [abep.nepo.unicamp.br]

- ↑ Start of the immigration to Brazil

- ↑ Thomas Skidmore. Racial ideas and social policies in Brazil, 1870-1940. In Richard Graham et al. The Idea of race in Latin America, 1870-1940 p. 23-25.

- ↑ "www.soleis.adv.br -- Divulgue este site".

Works cited

- Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0.

- Besouchet, Lídia (1993). Pedro II e o Século XIX (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. ISBN 978-85-209-0494-7.

- Janotti, Aldo (1990). O Marquês de Paraná: inícios de uma carreira política num momento crítico da história da nacionalidade (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia. ISBN 978-85-319-0512-4.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (1998). As barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-7164-837-1.