| Emydops Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull at the Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Family: | †Emydopidae Cluver and King, 1983 |

| Genus: | †Emydops Broom, 1912 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

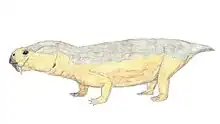

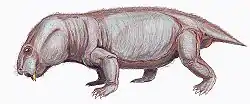

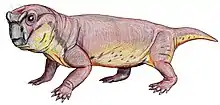

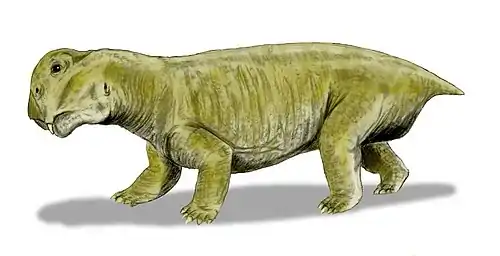

Emydops is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsids from the Middle Permian to Late Permian of what is now South Africa. The genus is generally small and herbivorous, sharing the dicynodont synapomorphy of bearing two tusks. In the following years, the genus grew to include fourteen species. Many of these species were erected on the basis of differences in the teeth and the positioning of the frontal and parietal bones.[1] A 2008 study narrowed Emydops down to two species, E. arctatus (first described by English paleontologist Richard Owen as Kistecephalus arctatus in 1876) and the newly described E. oweni.[2]

)_(18161883181).jpg.webp)

History and discovery

Emydops was first discovered and named in 1912 by Robert Broom, in which he described the species E. minor.[2][3][4] Although later on it was suggested that the genus included 13 more species, Frobisch and Reisz (2008) suggests that only E. oweni and E. arctatus are the only valid species of Emydops.[2]

With the appearance of E. minor marking the beginning of the stratigraphic range of Emydops in the Late Permian-aged Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone from the Karoo Basin of South Africa, it is argued that a specimen found in the vicinity of the Middle Permian to Late Permian Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone and Middle Permian Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone of Beauford West belongs to Emydops.[5] Whether the specimen is from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone or Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone, both indicate that Emydops stratigraphic range began earlier than it has been previously accepted.[5]

Description

Skull

The skull of Emydops is small, up to 5 cm (2 in) long.

The premaxillae and maxillae of Emydops are less pronounced than those of more mature dicynodonts, and they are generated downward as a distinct outer rim that is most developed around the canines. Anteriorly, the rim continues slightly downwards and forms the tip of the upper beak.[6] The orbits are positioned far anteriorly in the skull, and face forward and upward.[1] The temporal region is large in proportion to the face and provides attachment for the laterodorsal trigeminal musculature of enormous bulk. In dorsal view, the temporal vacuities are described to be large and the ventrolateral region of the cheek is deeply excavated. [6]

Convergently evolved from cynodonts, dicynodonts also have a secondary palate which consists of a broad, flat, horizontal plate formed anteriorly by the palatines. Additionally, it extends posteriorly by the palatines, which dip gently downward to the rear.[6]

The reflected lamina of the angular bone of Emydops is large and fan-shaped, like other small dicynodonts. However, unlike many dicynodonts, the reflected lamina of the angular bone of Emydops has a broad, thin, unsupported sheet that terminates in a long, free border rather than the sheet folding and converging anteriorly toward a marginal thickening on the angular body.[6] As well, a broadened lateral dentary shelf on the lower jaw serves as another distinguishing feature of the genus.[1]

Dentition

Most skulls of Emydops bear a pair of caniniform tusks, diagnostic of dicynodonts, There are generally three postcanine teeth present in the upper jaw of Emydops. They are arranged in a straight line parallel to the mandibular teeth. As seen in cross-section, the crowns of the maxillary postcanine teeth are unserrated and round to slightly widened.[6] In contrast, the mandible of Emydops consists of seven functional teeth, in which the crowns are described as pear-shaped: they have wide, blunt anterior edges and sharp, strongly serrated posterior edges.[6]

The holotype specimen of E. oweni is unusual in that it has two pairs of tusks. The second pair of tusks is not seen in any other dicynodont, and is a feature unique to the specimen. The extra tusks are considered a pathological feature; they are thought to have been the result of a mutation in the individual and are not considered a defining characteristic of the species.[2]

Systematics

Taxonomy

Robert Broom first came up with the name Emydops in 1912 when describing small dicynodonts with unserrated postcanines.[2][3][4] The validity of E. minor and the twelve additional species before E. oweni was uncertain until two important revisions of small dicynodonts were released in 1993 by King and Rubidge (1993) and Keyser (1993).[2][3][7] Keyser (1993) suggested that the genus be named Emydoses and only include some species previously described and not all of them.[2][3] Ray (2001) rejects this name and insists that Emydops should be kept due to taxonomic stability.[1][2] Eventually Angielczyk et al. (2005) was published, mentioning the possibility of E. arctatus [8] having priority over the other described species of Emydops. All of the species before E. oweni were restudied and their taxonomic status was reevaluated. Frobisch and Reisz (2008) argue that the thirteen species before the discovery of E. oweni all fall under E. arctatus.[2]

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from Kammerer et al. (2013).[9] The data matrix of Kammerer et al. (2013), a list of characteristics that was used in the analysis, was based on that of Kammerer et al. (2011), which followed a comprehensive taxonomic revision of Dicynodon.[10] Because of this, many of the relationships found by Kammerer et al. (2013) are the same as those found by Kammerer et al. (2011). However, several taxa were added to the analysis, including Tiarajudens Eubrachiosaurus, Shaanbeikannemeyeria, Zambiasaurus and many "outgroup" taxa (positioned outside Anomodontia), while other taxa were re-coded. As in Kammerer et al. (2011), the interrelationships of non-kannemeyeriiform dicynodontoids are weakly supported and thus vary between the analyses.[9]

| Anomodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Feeding

Dicynodonts were dominant tetrapod herbivores most of the Upper Permian, thanks to their masticatory apparatus.

When Emydops ate, the cutting of material happened at the beak when the external adductor muscles applied a vertical force (jaw elevated).[6] Later on in the masticatory cycle, the dentary teeth also did cutting when the external adductor muscles applied an even stronger horizontal force (jaw retracted).[6]

The bottom teeth of Emydops are described as pear-shaped: they have wide, blunt anterior edges and sharp, strongly serrated posterior edges, suggesting that the teeth were effective in cutting only when the jaw moved backwards.[6]

Paleoenvironment

Although speculated to originate from an earlier assemblage zone, it is well known that Emydops was found from the Late Permian Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone of the Karoo Basin, South Africa.[5] Other herbivorous dicynodonts were found in this assemblage zone such as Pristerodon, Diictodon, Tropidostoma, and Endothiodon.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Ray, S. (2001). "Small Permian dicynodonts from India" (PDF). Paleontological Research. 5 (3): 177–191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fröbisch, J.; Reisz, R.R. (2008). "A new species of Emydops (Synapsida, Anomodontia) and a discussion of dental variability and pathology in dicynodonts". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 770–787. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[770:ANSOES]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85594758.

- 1 2 3 4 Broom, Robert (1932). "The Mammal-like Reptiles of South Africa and the Origin of Mammals". H. F. & G.: 376 pp.

- 1 2 Keyser, A. W. (1993). "A re-evaluation of the smaller Endothiodontidae". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of South Africa: 82:1–53.

- 1 2 3 Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Fröbisch, Jörg; Smith, Roger M.H. "On the stratigraphic range of the dicynodont taxon Emydops (Therapsida: Anomodontia) in the Karoo Basin, South Africa". Palaeontologia Africana: 41, 23-33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Crompton, A. W.; Hotton III, Nicholas (1967). "Functional morphology of the masticatory apparatus of two dicynodonts (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Postilla. 109.

- ↑ King, Gillian M.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (1993). "A taxonomic revision of small dicynodonts with postcanine teeth". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 107 (2): 131-154. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1993.tb00218.x.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (1876). Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the collection of the British Museum. British Museum.

- 1 2 Kammerer, C. F.; Fröbisch, J. R.; Angielczyk, K. D. (2013). Farke, Andrew A (ed.). "On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e64203. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864203K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064203. PMC 3669350. PMID 23741307.

- ↑ Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Fröbisch, J. (2011). "A comprehensive taxonomic revision of Dicynodon (Therapsida, Anomodontia) and its implications for dicynodont phylogeny, biogeography, and biostratigraphy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (Suppl. 1): 1–158. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31S...1K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.627074. S2CID 84987497.