| Wanli Emperor 萬曆帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

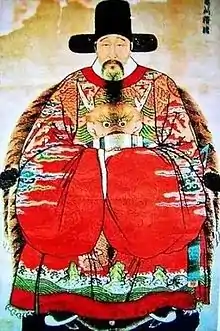

.jpg.webp) Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 19 July 1572 – 18 August 1620 | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 19 July 1572 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Longqing Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Taichang Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Regents | See list

| ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 4 September 1563 Jiajing 42, 17th day of the 8th month (嘉靖四十二年八月十七日) Shuntian Prefecture, North Zhili | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 August 1620 (aged 56) Wanli 48, 21st day of the 7th month (萬曆四十八年七月二十一日) Hongde Hall, Forbidden City | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Dingling Mausoleum, Ming tombs, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | Grand Empress Dowager Xiaojing

(died 1597) | ||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Longqing Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Dowager Xiaoding | ||||||||||||||||

| Wanli Emperor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 萬曆帝 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 万历帝 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Ten Thousand Calendars" Emperor | ||||||

| |||||||

The Wanli Emperor (4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shenzong of Ming (Chinese: 明神宗), personal name Zhu Yijun (Chinese: 朱翊鈞; pinyin: Zhū Yìjūn), art name Yuzhai (禹齋),[2] was the 14th emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was the third son of the Longqing Emperor. His reign of 48 years (1572–1620) was the longest among all the Ming dynasty emperors[1] and it witnessed several successes in his early and middle reign, followed by the decline of the dynasty as the emperor withdrew from his active role in government around 1600.

The Wanli Emperor ascended the throne at the age of nine. During the first ten years of his reign, the young emperor was assisted and effectively led by Grand Secretary and skilled administrator, Zhang Juzheng. With the support of the emperor's mother, Lady Li, and the imperial eunuchs led by Feng Bao, the country experienced economic and military prosperity, reaching a level of power not seen since the early 15th century. The emperor held great respect and appreciation for his Grand Secretary. However, as time passed, various factions within the government openly opposed Zhang, causing his influential position in the government and at court to become a burden for the monarch. In 1582, Zhang died and within months, the emperor dismissed Feng Bao. He then gained discretion and made significant changes to Zhang's administrative arrangements.

The Wanli era was marked by a significant boom in industry, particularly in the production of silk, cotton, and porcelain. Agriculture also experienced growth, and there was a notable increase in both interregional and foreign trade. This development had the strongest impact in Jiangnan, where cities such as Suzhou, Songjiang, Jiaxing, and Nanjing flourished. However, despite the overall economic growth of the empire, the state's finances remained in a poor state. While wealthy merchants and gentry enjoyed a life of splendor, the majority of peasants and day laborers continued to live in poverty.

In the military field, the closing decade of the 16th century was marked by three major campaigns, all of which were successful. The first of these was the rebellion of a large garrison at Ningxia, which resulted in the rebels taking control of the city and its surrounding area after eliminating the commanding generals. The rebels had a significant force of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers, while the city itself had a population of 300,000. In response, the Ming government assembled a force of 40,000 soldiers to quell the rebellion. By mid-October 1592, the city had been conquered and Ming troops were able to be moved to the opposite side of the empire, to Korea. In the same year, the de facto ruler of Japan, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, launched an invasion of Korea with 200,000 soldiers. In response, the Wanli Emperor immediately sent 3,000 men, but they were unable to withstand the Japanese forces. As a result, the emperor increased the Chinese army in Korea to 40,000 soldiers. The combined Korean-Chinese forces gained the upper hand, and the Japanese were pushed out of most of Korea and forced to retreat to the southeast coast by 1593. Four years later, in 1597, the Japanese launched a second invasion, but were ultimately defeated and forced to withdraw after the death of Hideyoshi the following year. The third major conflict during this time was the suppression of Yang Yinglong's rebellion in southwest China from 1587 to 1600. Due to the ongoing war with Japan, Ming forces were only able to concentrate in the southwest from 1599. However, once they were able to do so, a Ming army of over 200,000 soldiers was able to quickly defeat and suppress the rebellion within a few months.

Over time, the emperor grew increasingly disillusioned with the constant moralizing attacks and counterattacks from officials, causing him to become increasingly isolated. In the 1580s and 1590s, he attempted to promote his third son, Zhu Changxun (the son of his favorite concubine, Lady Zheng), as crown prince, but faced strong opposition from officials. This led to ongoing conflicts between the emperor and his ministers for over fifteen years. Eventually, the emperor gave in and appointed his eldest son, Zhu Changluo (later the Taichang Emperor), as crown prince in October 1601. In 1596, the Wanli Emperor attempted to establish a parallel administration composed of eunuchs, separate from the officials who had traditionally governed the empire. However, this effort was abandoned in 1606. As a result, the governance of the country remained in the hands of Confucian intellectuals, who were often embroiled in disputes with each other. The opposition Donglin movement continued to criticize the emperor and his followers, while pro-government officials were divided based on their regional origins.

In the final years of the Wanli Emperor's reign, the Jurchens grew stronger on the northeastern frontiers and posed a significant threat. In 1619, they defeated the Ming armies in the Battle of Sarhu and captured part of Liaodong.

Childhood and accession to the throne

Zhu Yijun was born on 4 September 1563 to Zhu Zaiji, the heir to the throne of the Ming dynasty, and one of his concubines, Lady Li. He was the third son of Zhu Zaiji, but unfortunately, both of his older brothers died in early childhood before 1563. He did have a younger brother, Zhu Yiliu (朱翊鏐; 1568–1614), who was created Prince of Lu in 1571.

Zhu Zaiji became emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1567 and reigned as the Longqing Emperor, but he died five years later on 5 July 1572. Zhu Yijun then ascended the throne two weeks later on 19 July 1572. Before his death, the Longqing Emperor instructed minister Zhang Juzheng to take charge of state affairs and become a devoted adviser to the young emperor.

The Wanli Emperor was known for his restless and energetic nature during his youth.[3] He was described as a quick learner,[4] intelligent,[3][4] and perceptive, always staying well-informed about the happenings in the empire.[3] Zhang Juzheng assigned eight teachers to educate the Wanli Emperor in Confucianism, history, and calligraphy. The history lessons focused on teaching him about good and bad examples of governance, and Zhang Juzheng personally compiled a collection of historical stories for the emperor to learn from. However, the Wanli Emperor's fascination with calligraphy concerned Zhang, who feared that this "empty pastime" would distract him from his duties as a statesman. As a result, Zhang gradually stopped the Wanli Empror's calligraphy lessons.[5] From 1583 to 1588, the Wanli Emperor visited several mausoleums near Beijing and paid attention to the training of the palace guard.[6] However, his mother, Zhang Juzheng,[3] and high-ranking officials in Beijing were worried that he would become a ruler similar to the Zhengde Emperor (reigned 1505–1521),[6] and discouraged him from traveling outside the Forbidden City and pursuing his interests in the military, horse riding, and archery.[3][6] Under their pressure, the Wanli Emperor stopped leaving Beijing after 1588 and stopped participating in public sacrifices after 1591. He also canceled the morning audience (held before dawn) and the evening study of Confucianism (after sunset).[7] In his youth, the Wanli Emperor was obedient to his mother and showed respect towards eunuchs and grand secretaries. However, as he grew older, he became cynical and skeptical towards rituals and bureaucrats.[6] His opposition to ritualized royal duties linked him to his grandfather the Jiajing Emperor (reigned 1521–1567), but he lacked the Jiajing Emperor's decisiveness and flamboyance. Instead of the Jiajing Emperor's passion for Taoism, the Wanli Emperor leaned towards Buddhism.[6]

In the first period of his rule, he displayed a strong commitment to the well-being of his people, actively combating corruption and striving to improve border defense. His mother, a devout Buddhist, had a significant influence on him, leading him to rarely impose the death penalty. However, one punished official claimed that his leniency was sometimes excessive. Despite this, he was not afraid to use violence against offending officials, although he did not make it a regular practice. He was known to be both vulnerable and vengeful, but also generous.[3] However, since the mid-1580s, he began to gain weight[7] and his health deteriorated. In 1589, he cited long-term dizziness, accompanied by fevers, heatstroke, eczema, diarrhea, and general weakness as reasons for his absence from audiences. It is believed that his health issues were linked to his regular use of opium.[8]

Zhang Juzheng and his mother raised the Wanli Emperor to be modest in material possessions and exemplary in behavior, which he saw as a humiliation that he never forgot. However, upon learning that Zhang Juzheng himself lived in luxury, the Wanli Emperor was deeply affected. This display of double standards hardened his attitude towards officials and made him cynical about moral challenges. Two years after Zhang Juzheng's death, his family was accused of illegal land dealings, and the Wanli Emperor severely punished them by confiscating their property and sending Zhang's sons to the border troops.[9]

Wanli as emperor

Zhang Juzheng government (1572–1582)

At the end of the Longqing Emperor's reign, the Grand Secretariat and Government were headed by Senior Grand Secretary and Minister of Rites Gao Gong. However, after the Wanli Emperor's accession, the eunuch Feng Bao (馮保), head of the Directorate of Ceremonies (the most important eunuch office in the imperial palace), worked with Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng to depose Gao Gong. Zhang Juzheng then took over as head of the Grand Secretariat and remained in power for ten years until his death in 1582.[11] In response to the Mongol raids in the 1550s, Zhang aimed to "enrich the country and strengthen the army", using legalistic methods rather than Confucian ones.[12] He sought to centralize the government and increase the emperor's authority at the expense of local interests by streamlining the administration and strengthening the military.[13] This included closing local academies and placing the investigating censors under the Grand Secretariat's control.[13] Zhang had the support of eunuchs, particularly Feng Bao, and the emperor's mother,[14] who acted as regent. He was able to handpick his colleagues in the Grand Secretariat and informally control the Ministry of Rites and the Censorate, appointing his followers to important positions in central offices and regions. This gave him significant influence in the government, although he did not have the authority to issue orders or demands.[14] Zhang also attempted to redirect the control officials from seeking revenge against each other and instead focus on collecting taxes and suppressing bandits. As a result, the efficiency of the Ming state administration improved between 1572 and 1582,[15] reaching a level that had only been achieved in the early days of the empire.[16]

Zhang Juzheng implemented a series of reforms during his time in office, including the conversion of tax payments from goods to silver (known as the Single whip reform), changes to the military peasant system,[12] and between 1572 and 1579, revised the accounts of county offices regarding corvée labor and various fees and surcharges.[15] In 1580–1582, a new cadastre was also created.[17] These reforms were formalized across the empire with the publication of revised lists of taxpayers' duties, now converted to a unified payment in silver.[15] As part of the administrative reforms, unnecessary activities were abolished or limited, the number of Confucian students receiving state support was reduced, and provincial authorities were urged to only require one-third of the previous amount of corvée labor. Additionally, the services provided by post offices were reduced. Despite these changes, taxes remained at their original level and tax arrears were strictly enforced. Zhang Juzheng was able to accumulate a surplus of income over expenditure.[18] This was a significant achievement, as the Ming state typically operated without reserves in the 16th century. However, Zhang Juzheng's administration was able to save money and improve tax collection, resulting in considerable reserves. In 1582, the granaries around the capital held nine years' worth of grain, the treasury of the Ministry of Revenue contained 6 million liang (about 223 tons) of silver, the Court of the Imperial Stud (太僕寺) held another 4 million, and an additional 2.5 million was available in Nanjing. Smaller reserves were also available to provincial administrations in Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Guangxi. Despite these achievements, there were no institutional changes during Zhang Juzheng's time in office. He simply made existing processes more efficient under the slogan of returning to the order from the beginnings of the empire.[19]

As a proponent of peace with the Mongols, Zhang Juzheng rejected the proposal of Minister of War Tan Lun for a pre-emptive strike against them. Instead, he ordered Qi Jiguang, commander of the northeastern border, to maintain an armed peace.[18] This decision not only allowed for a reduction in the border army, but also resulted in the return of surplus soldiers to their family farms.[15] Zhang Juzheng not only rejected the notion that military affairs were less important than civilian ones, but also challenged the dominance of civilian dignitaries over military leaders. He appointed capable military leaders such as Qi Jiguang, Wang Chonggu (王崇古), Tan Lun, Liang Menglong (梁夢龍), and Li Chengliang to positions of responsibility. Additionally, he implemented a combination of defensive and offensive measures to strengthen border defenses and fostered peaceful relations with neighboring countries by opening border markets, particularly in the northwest.[20]

Zhang Juzheng's actions were within the bounds of existing legislation, but critics viewed them as an abuse of power to promote his followers and exert illegitimate pressure on officials. However, open criticism was rare until his father's death in 1577. According to the law, Zhang was supposed to leave office due to mourning, but the emperor chose to keep him in office. This was not unprecedented, but criticism of disrespect for parents was widespread.[16] Despite the fact that the most vocal critics were punished with beatings, Zhang Juzheng's reputation was damaged. In an attempt to suppress opposition, Zhang then enforced an extraordinary self-evaluation of all high-ranking officials,[21] resulting in the elimination of around fifty opponents.[22]

Zhang Juzheng died on 9 July 1582. After his death, he was accused of the typical offenses of high officials, including bribery, living in luxury, promoting unqualified supporters, abusing power, and silencing critics.[23] After Zhang Juzheng's death, his followers among the officials were dismissed,[24] and in the beginning of 1583, Feng Bao also lost his position.[25] However, the emperor protected the officers, which boosted their morale to a level not seen since the mid-15th century. The Wanli Emperor's more aggressive military policy was based on Zhang's successes,[13] as he attempted to replace static defense with more offensive tactics and appointed only officials with military experience to lead the Ministry of War.[24] The emperor also shared Zhang Juzheng's distrust of local and regional authorities and opposition to factional politics.[13] Like Zhang Juzheng, the Wanli Emperor preferred to solve real problems rather than engage in "empty talk"[lower-alpha 2] and factional conflicts.[26]

Anti-Zhang opposition government (1582–1596)

After Zhang's death, a coalition formed between the emperor's mother,[27] the Grand Secretaries, the Ministry of Personnel, and the Censorate to ensure efficient administration of the empire. This alliance was opposed by the opposition, who deemed it illegal.[28] However, with the absence of a strong statesman in the Grand Secretariat, there was no one to bring the administration under control.[29] Both the emperor and opposition officials feared the concentration of power in the Grand Secretariat and worked to prevent it.[30] From 1582 to 1591, the Grand Secretariat was briefly led by Zhang Siwei (張四維) and then for eight years by Shen Shixing. Shen Shixing attempted to find compromises between the monarch and the bureaucracy, while also tolerating criticism and respecting the decisions of ministries and the censors. However, his efforts to create a cooperative and cohesive atmosphere were unsuccessful.[28] In 1590, the Grand Secretariat's alliance with the leadership of the Ministry of Personnel and the Censorate fell apart, causing Shen Shixing to lose much of his influence.[31] He was eventually forced to resign in 1591 due to his approach to the succession issue, which had lost him the confidence of opposition officials.[29]

After 1582, the emperor chose the leaders of the Grand Secretariat from among the opponents of Zhang Juzheng (after Shen Shixing, the position was held by Wang Jiaping (王家屏), Wang Xijue, and Zhao Zhigao (趙志皋) until 1601). Except for the short-lived Wang Jiaping, all of Zhang's successors (including Shen Yiguan (沈一貫), Zhu Geng (朱賡), Li Tinhji (李廷機), Ye Xianggao, and Fang Congzhe (方從哲)) fell out of favor and were either accused by censors during their lifetime or posthumously.[32]

The anti-Zhang opposition, led by Gu Xiancheng, was successful in condemning him and purging his followers from the bureaucracy after his death.[33] However, this also created an opportunity for the censors to criticize higher-ranking officials, which angered the monarch and caused dissatisfaction because the critics did not offer any positive solutions.[9] As a result, Zhang's opponents became embroiled in numerous disputes, hindering the restoration of a strong centralized government.[33] From 1585, the censors also began to criticize the emperor's private life.[9] This criticism was fueled by the emperor's reluctance to impose harsh punishments, which emboldened the critics.[34] In response, the Wanli Emperor tried to silence their informers among his servants[9] and gradually stopped responding to comments about himself.[34] However, in 1588, the Wanli Emperor's censors accused him of accepting a bribe from one of his eunuchs, which shocked the emperor and caused him to withdraw from cooperating with officials. He reduced his contact with them to a minimum and canceled the morning audience. He only appeared in public at celebrations of military victories and communication with the bureaucracy was done through written reports, to which he may or may not have responded. Towards the end of his reign, he also hindered personnel changes in offices, leaving positions vacant and allowing officials to leave without his written consent–which was illegal, but went unpunished.[35] As a result, by 1603, nine positions of regional inspectors (out of 13) were vacant for a long time, and in 1604, almost half of the prefects and over half of the ministers and deputy ministers in both capitals were vacant.[36] The emperor also deliberately left many positions vacant in the eunuch offices of the palace, particularly the position of head of the Directorate of Ceremonies, in an attempt to weaken communication between eunuchs and officials.[37] This also resulted in significant financial savings from unoccupied seats.[36]

The emperor's lack of involvement in official positions did not affect the administration's responsibility for tax collection.[36] In times of military or other serious issues, he sought advice from responsible officials in Ministries and the Censorate, and was not hesitant to appoint capable individuals outside of the traditional hierarchy to handle the situation. However, he had a lack of trust in the regular administration and often found ways to bypass it.[38] While he may have left some memoranda unanswered, he actively responded to others. Despite leaving some high positions vacant, the authorities were able to function under the guidance of deputies and the country's administration continued to run smoothly. Assistance was provided to those affected by famine, rebellions were suppressed, border conflicts were resolved, and infrastructure was maintained.[39]

Hundreds of memoranda arrived on the Wanli Emperor's desk daily, but he only read and decided on a handful of them. The rest were handled by commissioned eunuchs, who were equipped with the imperial "red brush". These eunuchs mostly confirmed the recommendations and proposals of the Grand Secretaries, but occasionally made different decisions if they believed the emperor would not agree with the Grand Secretaries' proposals.[40]

Despite his desire to reform the civil service, the emperor was unable to do so, and he also did not want to simply confirm the decisions of the officials. Both sides–the emperor and the bureaucrats–wanted the other to behave properly, but their efforts were unsuccessful and only served to paralyze each other.[35] As a result of these disputes at the center, the state's control over the countryside weakened.[33]

Succession dispute (1586–1614)

In 1586, the issue of succession arose when the emperor elevated his favorite concubine, Lady Zheng, to the rank of "Imperial Noble Consort" (Huang Guifei),[34][41] placing her only one rank below the empress and above all other concubines, including Lady Wang, mother of the emperor's eldest son Zhu Changluo (1582–1620). This made it clear to those around him that he favored the son of Lady Zheng, Zhu Changxun (1586–1641)–his third son (the second had died in infancy)–over Zhu Changluo as his successor. This caused a division among the bureaucracy; some officials defended the rights of the first son based on legal primogeniture, while others aligned themselves with Lady Zheng's son.[34] In response to the widespread support for the eldest son's rights among officials, the emperor postponed his decision.[34] He justified the delay by stating that he was waiting for a son from the empress.[42] When asked to appoint Zhu Changluo as the crown prince at the age of eight so that his education could officially begin, the emperor again defended himself by saying that princes were traditionally taught by eunuchs.[43]

In 1589, the emperor agreed to appoint Zhu Changluo as his successor. However, this decision was opposed by Lady Zheng, causing a wave of controversy and, two years later, even arrests when a pamphlet accusing her of conspiring with high officials against the emperor's eldest son spread in Beijing. In an attempt to improve her public image, the emperor made efforts to portray Lady Zheng in a favorable light.[41] This reached its peak in 1594 when he supported her efforts to aid the victims of a famine in Henan. He ordered all Beijing officials of the fifth rank and above to contribute to her cause from their incomes.[44]

The failure to appoint a successor sparked frequent protests from both opposition-minded officials and high dignitaries, such as Grand Secretaries Shen Shixing (in office 1578–91) and Wang Xijue (in office 1584–91 and 1593–94).[34] The rights of Zhu Changluo were also supported by the empress[45] and the emperor's mother.[42] However, it wasn't until 1601, after facing pressure from another round of protests and requests, that Wanli finally appointed Zhu Changluo as crown prince.[42][46] At the same time, Zhu Changxun was given the title of Prince of Fu,[35] but he was kept in Beijing instead of being sent to the province as originally planned when he turned eighteen in 1604. This fueled rumors that the question of succession was still unresolved.[47] It wasn't until 1614, after numerous appeals and protests against inaction, that the emperor finally sent the prince to his provincial seat.[46][48] This decision was only made after the emperor's mother firmly advocated for it.[42]

Related to the succession debates was the "Case of the Wooden Staff Assault" (梃擊案), which greatly damaged the ruler's reputation. In late May 1615, a man with a wooden staff was detained at the crown prince's palace. From the subsequent investigation, it was discovered that the man, Zhang Chai (張差), was mentally unstable[49] and had attempted to use his wooden staff to settle a dispute with two eunuchs. Initially, it was decided that he would be executed to resolve the issue.[37] However, Wang Zhicai (王之寀), a prison official, intervened and disputed the claim that Zhang Chai was insane. He pushed for a public investigation involving the Ministry of Justice. This new version of events suggested that Zhang Chai was actually of sound mind and had been invited into the palace by two eunuchs close to Lady Zheng and her brother. This raised suspicions that their true intention was to assassinate the crown prince and replace him with Lady Zheng's son.[50] This caused quite a stir at court. In response, the Wanli Emperor took the unprecedented step of summoning all civilian and military officials employed in Beijing and appearing before them with his family–the crown prince, his sons and daughter. He scolded the officials for doubting his relationship with the crown prince, whom he trusted and relied on. The crown prince himself confirmed their close relationship and requested an end to the matter. Ultimately, the emperor decided to execute Zhang Chai and the two eunuchs involved in the case.[51] However, officials from the Ministry of Justice opposed the execution and demanded further investigation. A compromise was reached through the mediation of the Grand Secretaries–Zhang Chai was executed the following day, while the suspected eunuchs were to be interrogated. The interrogation did take place, but both eunuchs remained under the supervision of the emperor's eunuchs. On the fifth day after the emperor's speech, the officials were informed that the eunuchs had died.[50] The case then quieted down.

Mines and Taxes (1596–1606)

.svg.png.webp)

In August 1596, due to poor tax collection and the depletion of the treasury from the costly restoration of the Forbidden City palaces destroyed by fire in April of that year, the Wanli Emperor made the decision to accept proposals for silver mining that had been suggested by lower-level administrators for several years. He dispatched a team consisting of eunuchs, Imperial Guard officers, and representatives from the Ministry of Revenue to the outskirts of Beijing to establish new silver mines. He also sent an Imperial Guard officer to Henan province with the same task, and within a few weeks, other officers and eunuchs were sent to Shandong, Shaanxi, Zhejiang, and Shanxi provinces.[52] There was a long-standing tradition of sending eunuchs to various regions, as the business, trade, and mining industries provided opportunities for them to earn income.[53] However, within a few days, this initiative was met with opposition from local authorities in Beijing, who raised concerns about the potential threat to imperial tombs in the mountains near Beijing and the difficulty of recruiting miners who were still engaged in illegal mining. In response, the emperor designated a protective zone for the tombs, but did not cancel the mining operation. He also appointed wealthy individuals from the local gentry to manage the mines and oversee necessary investments.[52]

Confucian officials, who were concerned about the erosion of their authority,[53] opposed the emperor's initiative on ideological grounds, as they believed that the state should not engage in business and compete with the people for profit. They also objected to the emperor's involvement in the mining industry, as it required the employment of miners who were considered untrustworthy and derogatorily referred to as "mining bandits." Another reason for the gentry and officials opposition was the fact that eunuchs, a rival power group, were in charge of the mining operations. Furthermore, mining for silver was a complex task that required expertise and skills that the emperor's eunuchs did not possess. To address this issue, the emperor appointed wealthy local individuals as mine managers, who were responsible for paying the mining tax and delivering the silver, regardless of the profitability of the mine. As a result, the mining of silver shifted from underground to the coffers of the wealthy, effectively taxing them. American historian Harry Miller bluntly described Wan-li's actions as an "economic war against the wealthy".[52]

After the war in Korea reignited in 1597, the emperor made increased efforts to raise additional funds.[54] Due to his lack of trust in the gentry, he began to establish an alternative eunuch regional administration. Gradually, the mining tax commissioners (kuangshi 礦使; literally “mining envoy”) gained control over the collection of trade and other taxes, in addition to the mining tax (kuangshui 礦稅) which was officially approved by the emperor in 1598–1599.[55] The emperor granted these commissioners the authority to supervise the county and prefectural authorities, and even the grand coordinators. As a result, the imperial commissioners no longer had to consider the opinions of local civil or military authorities. Instead, they could assign tasks to them and even imprison them if they resisted. While the emperor disregarded the protests of officials against the mining tax and the actions of the eunuchs, he closely monitored the reports and proposals of the eunuchs and responded promptly, often on the same day they arrived in Beijing.[54] In 1599, he dispatched eunuchs to major ports, where they took over the powers of official civil administration.[56] The emperor finally resolved disputes with officials defending their powers in the spring of 1599 by officially transferring the collection of taxes to mining commissioners.[57] This expansion of eunuch powers and their operations earned the emperor a reputation among Confucian-oriented intellectuals as one of the most avaricious rulers in Chinese history, constantly seeking ways to fill his personal coffers at the expense of government revenue.[37]

According to American historian Richard von Glahn, tax revenue from silver mines increased significantly from a few hundred kilograms per year before 1597 to an average of 3,650 kg per year in 1597–1606. In the most successful year of 1603, the revenue reached 6,650 kg, accounting for approximately 30% of mining.[58] According to estimates by modern Chinese historians Wang Chunyu and Tu Wan-yuan, the mining tax earned the state an additional 3 million liang (110 tons) of silver, with the eunuch commissioners retaining eight or nine times more. Another estimate suggests that in 1596–1606, the mine commissioners supplied the state with at least 5.96 million liang of silver, but kept 40–50 million for themselves. While officials commonly profited from their positions, eunuchs were known to pocket a significantly larger portion of the collected funds.[59]

At the turn of the years 1605/1606, the emperor realized that not only gentry officials, but also eunuchs, were corrupt. He also recognized that the mining tax was causing more harm than good. As a result, in January 1606, he made the decision to abandon the attempt at alternative administration and issued an edict to abolish state mining operations. Tax collection was then returned to the traditional authorities.[60] The gentry not only suffered financially from the eunuchs' actions, but also lost control over the financial transactions between the people and the state. This loss of control was a significant blow to their perceived dominance over the people. It was a humiliating experience and disrupted the natural order of things. However, by 1606, the gentry regained their dominance over both the people and the state as a whole.[61]

Reforms in the selection and evaluation of officials

In the Ming administrative system, ultimate authority rested with the monarch. However, it required an energetic and competent ruler to effectively carry out this power. In cases where the ruler was not capable, the system of checks and balances resulted in collective leadership.[62] This was due to the dispersion of power among various authorities. In the mid-15th century, a system of collective debates (huiguan tuiju; literally "to rally officials and to recommend collectively") was established to address issues that were beyond the scope of one department.[63] These gatherings involved dozens of officials discussing political and personnel matters. As a result, the importance of public opinion (gonglun; 公論) grew and the autocratic power of the monarch was limited.[64]

During the Wanli Emperor's reign, one of the issues that was resolved collectively was the appointment of high state dignitaries.[64] At the beginning of his reign, Zhang Juzheng successfully abolished collective debates, giving the emperor the power to appoint high officials based on his own suggestions. However, after Zhang's death, the debates were reinstated and the emperor's power was once again limited.[63] Despite this, Wanli attempted to overcome these restrictions, such as in 1591 when he announced his decision to appoint the current Minister of Rites, Zhao Zhigao, as Senior Grand Secretary without consulting with other officials. This decision was met with criticism from Minister of Personnel, Lu Guangzu, who argued that it violated proper procedure and undermined the fairness and credibility of the government's decision-making processes. Lu and others believed that collective consideration of candidates in open public debate was a more impartial and fair method, as it eliminated individual bias and ignorance. In response to the criticism, the emperor partially retreated and promised to follow the proper procedure in the future. However, he continued to occasionally appoint high dignitaries without collective debate, which always sparked protests from officials.[63]

In the late Ming period, there was a widespread belief that public opinion held more weight than individual opinions. This was evident in the way political and administrative issues were addressed, with decision-making being based on gathering information and opinions from officials through questionnaires and voting ballots.[65] This also had an impact on the evaluation of officials, as their performance began to be judged not only by their superiors but also by the wider community. In 1595, Minister of Personnel Sun Piyang conducted a questionnaire survey on the conditions of several offices and used the results to persuade the Wanli Emperor to dismiss a certain official from Zhejiang. The survey had received a large number of negative comments, including accusations of corruption and other crimes. This unprecedented event sparked a heated debate, with Zhao Zhigao arguing that anonymous questionnaires should not be the main criteria for evaluation and that no one should be accused of criminal offenses based on unverified information from anonymous sources.[65] Sun defended himself by stating that solid evidence against the individual was not necessary, as they were not being accused or standing trial. He believed that in evaluating officials, it was sufficient for him to impartially discover the widely held opinion of the individual's recklessness through the survey.[66]

The reform of civil servant evaluations resulted in their careers being dependent on their reputation, as determined by the ministry and censors through anonymous surveys filled out by their colleagues.[66] This shift, along with collective debates, elevated the significance of public opinion during the Wanli Emperor's reign, leading to intense public debates and conflicts as groups of officials vied for control of public opinion while the monarch's authority and the weight of his voice declined.[67]

Donglin movement and factional disputes (1606–1620)

In 1604,[68][69] Gu Xiancheng, with the suggestion of his friend Gao Panlong (高攀龍), established the Donglin Academy in Wuxi, located in Jiangnan. The academy served as a hub for discussions and meetings.[70] With the support of local authorities and the gentry, the academy quickly gained prominence. As the founders had been out of politics for many years, the government did not view it as a threat.[71] The academy attracted hundreds of intellectuals and soon became a significant intellectual center in all of China. It also inspired the creation of similar centers in nearby prefectures,[70] forming a network of associations and circles.[69]

According to the academy, they was a group of officials who advocated for strict adherence to Confucian morality.[72] The supporters of the Donglin movement believed that living an exemplary life was essential for cultivating moral character, and they did not differentiate between private and public morality. They believed that one's moral cultivation should begin with the mind/heart, then extend to one's home, surroundings, and public life. This belief was exemplified by Gao Panlong.[73] However, they viewed Zhang Juzheng's decision to not mourn for his father as a sign of being an unprincipled profiteer. They also criticized the emperor for hesitating to confirm the succession of his eldest son, considering it unethical and unacceptable.[72] The Donhlin movement promoted a system of government based on Confucian values, particularly the values of the patriarchal family, which were extended to the entire state. They believed that the local administration should be led by the educated gentry, who would guide the people. In this context, the technical aspects of governance were considered unimportant[74] and any issues with the organization of administration were addressed by promoting Confucian virtues, preaching morality, and emphasizing self-sacrifice for higher goals.[75] Disputes within the movement centered around moral values and qualities, with opponents being accused of immoral behavior rather than professional incompetence.[76] The emphasis on morality allowed the Donglin movement to claim that they were not pursuing selfish goals, but were united by universal and true moral principles.[70] Although the leaders of the movement did not return to office until the end of the Wanli Emperor's reign, it had a significant influence among junior officials in Beijing.[71]

They opposed the concentration of power in the Grand Secretariat and the Ministries, advocating for the independence of the Censorate. They also called for limitations on the activities of eunuchs within the imperial palace.[73] Their stance on succession was based on principles, arguing that the ruler does not have the right to unilaterally change fundamental laws of the empire, including succession rules.[76] However, their emphasis on decentralization and prioritizing morality and ideology over pragmatism hindered effective governance of the empire, which was already challenging due to its size and population.[75]

The tendency to equate personal virtue with administrative talent led to morality becoming the main target in factional disputes.[77] The regular evaluation of the capital officials was often used to eliminate opponents. In 1577, Zhang Juzheng used this type of evaluation for the first time, resulting in the removal of 51 of his opponents. Another evaluation in 1581 led to the dismissal of 264 officials in the capital and 67 in Nanjing,[22] which was a significant purge considering that during the late Ming period, there were over a thousand officials serving in the central government in Beijing and almost four hundred in Nanjing.[78] In 1587, only 31 jinshi were removed by Gand Secretary Shen Shixing, but none from the Ministry of Personnel, the Hanlin Academy, and the Censorate, where factional disputes were common. However, censors also demanded the dismissal of the Minister of Works He Qiming (何起鳴), apparently for political reasons (as a supporter of Zhang Juzheng), just a month after his appointment, which angered the emperor. The minister was forced to leave, and the emperor also dismissed the head of the Censorate and transferred the responsible inspectors to the provinces. This sparked protests against the "emperor's interference in the independence of the Censorate".[22]

In the 1593 evaluation, the Donglins utilized their positions in the Ministry of Personnel and the Censorate to eliminate the followers of the Grand Secretaries. The newly appointed Senior Grand Secretary, Wang Xijue, was unable to support his party members. He did, however, request the dismissal of several organizers of the purge during additional evaluations. The head of the Censorate opposed this, but the emperor ultimately agreed,[79] sparking further protests from junior officials, including future founders of the Donglin Academy.[80] By the time of the 1599 evaluation, the Donglin opposition had lost its influence, resulting in a more peaceful evaluation.[81]

However, in the 1605 evaluation, the Donglin movement once again attacked their opponents, and through Wen Chun (溫純), the head of the Censorate, and Yang Shiqiao (楊時喬), Vice Minister of Personnel, demanded the dismissal of 207 officials from the capital and 73 from Nanjing. However, the emperor did not agree to such a large-scale purge and explicitly stated that several of the accused officials should remain in their positions. This was an unprecedented refusal and sparked sharp criticism, leading to a months-long debate filled with mutual recriminations. Even Heaven seemed to intervene when lightning struck the Temple of Heaven. Eventually, the accused officials were forced to resign, but so were the organizers of the purge, including Grand Secretary Shen Yiguan, the following year. While the Donglins were successful in dismissing their opponents, they did not have suitable candidates for top positions.[82] And even when a candidate like Li Sancai emerged, he was thwarted in the same way—through an attack on his moral integrity—in Li's case, through bribery. This was also the first instance where a connection to the Donglin movement was used as an argument against a candidate.[83]

In the 1611 evaluation, two anti-Donglin factions clashed, resulting in the downfall of their leaders (Tang Binyin (湯賓尹), Chancellor of Nanking University, and Gu Tianjun (顧天俊), teacher of the heir apparent). The career of the highest-ranking Donglin sympathizer, Vice Minister of Personnel and Hanlin Academy scholar, Wang Tu (王圖), was also ruined. In the 1617 evaluation, three cliques based on regional origin were in conflict, formed by anti-Donglin censors.[84] In the last decade of the Wanli Emperor's reign, the spineless bureaucrat Fang Congzhe led the Grand Secretariat, while the emperor left many high administrative positions vacant for long periods and simply ignored polemical memoranda.[84]

Legacy and death

Some scholars believe that the Wanli Emperor's reign was a significant factor contributing to the decline of the Ming dynasty. He refused to play the emperor's role in government, and delegated many responsibilities to eunuchs, who made up their own faction. The official administration was so dissatisfied that a group of scholars and political activists loyal to the thoughts of [[Zhu

The Wanli Emperor died in 1620 and was buried in the Dingling Mausoleum among the Ming tombs on the outskirts of Beijing. His tomb is one of the biggest in the vicinity and one of only two that are open to the public. The tomb was excavated in 1956, and remains the only imperial tomb that had been excavated since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

In 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards stormed the Dingling Mausoleum, and dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and his two empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously denounced and burned after photographs were taken of their skulls.[85] Thousands of other artifacts were also destroyed.[86]

In 1997, China's Ministry of Public Security published a book on the history of drug abuse. It alleged that the Wanli Emperor's remains had been examined in 1958 and found to contain morphine residues at levels which indicate that he had been a heavy and habitual user of opium.[87]

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Jang Tae-sung in the 2015 South Korean television series The Jingbirok: A Memoir of Imjin War.[88]

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Xiaoduanxian, of the Wang clan (孝端顯皇后 王氏; 7 November 1564 – 7 May 1620), personal name Xijie (喜姐)

Titles: Empress (皇后)- Princess Rongchang (榮昌公主; 1582–1647), personal name Xuanying (軒媖), first daughter

- Married Yang Chunyuan (楊春元; 1582–1616) in 1597, and had issue (five sons)

- Princess Rongchang (榮昌公主; 1582–1647), personal name Xuanying (軒媖), first daughter

- Empress Dowager Xiaojing, of the Wang clan (孝靖皇太后 王氏; 27 February 1565 – 18 October 1611)

Titles: Consort Gong (恭妃) → Noble Consort Gong (恭貴妃) → Imperial Noble Consort Cisheng (慈生皇貴妃)- Zhu Changluo, the Taichang Emperor (光宗 朱常洛; 28 August 1582 – 26 September 1620), first son

- Princess Yunmeng (雲夢公主; 1584–1587), personal name Xuanyuan (軒嫄), fourth daughter

- Grand Empress Dowager Xiaoning, of the Zheng clan (孝寧太皇太后 鄭氏; 1565–1630)

Titles: Imperial Concubine Shu (淑嬪) → Consort De (德妃) → Noble Consort (貴妃)- Princess Yunhe (雲和公主; 1584–1590), personal name Xuanshu (軒姝), second daughter

- Zhu Changxu, Prince Ai of Bin (邠哀王 朱常溆; 19 January 1585), second son

- Zhu Changxun, Prince Zhong of Fu (福忠王 朱常洵; 22 February 1586 – 2 March 1641), third son

- Zhu Changzhi, Prince Hai of Yuan (沅懷王 朱常治; 10 October 1587 – 5 September 1588), fourth son

- Princess Lingqiu (靈丘公主; 1588–1589), personal name Xuanyao (軒姚), sixth daughter

- Princess Shouning (壽寧公主; 1592–1634), personal name Xuanwei (軒媁), seventh daughter

- Married Ran Xingrang (冉興讓; d. 1644) in 1609, and had issue (one son)

- Grand Empress Dowager Xiaojing, of the Li clan (孝敬太皇太后 李氏; d. 1597)

Titles: Consort (妃)- Zhu Changrun, Prince of Hui (惠王 朱常潤; 7 December 1594 – 29 June 1646), sixth son

- Zhu Changying, Prince Duan of Gui (桂端王 朱常瀛; 25 April 1597 – 21 December 1645), seventh son

- Consort Xuanyizhao, of the Li clan (宣懿昭妃; 1557–1642)

- Consort Ronghuiyi, of the Yang clan (榮惠宜妃 楊氏; d. 1581)

- Consort Wenjingshun, of the Chang clan (溫靜順妃 常氏; 1568–1594)

- Consort Duanjingrong, of the Wang clan (端靖榮妃 王氏; d. 1591)

- Princess Jingle (靜樂公主; 8 July 1584 – 12 November 1585), personal name Xuangui (軒媯), third daughter

- Consort Zhuangjingde, of the Xu clan (莊靖德妃 許氏; d. 1602)

- Consort Duan, of the Zhou clan (端妃 周氏)

- Zhu Changhao, Prince of Rui (瑞王 朱常浩; 27 September 1591 – 24 July 1644), fifth son

- Consort Qinghuishun, of the Li clan (清惠順妃 李氏; d. 1623)

- Zhu Changpu, Prince Si of Yong (永思王 朱常溥; 1604–1606), eighth son

- Princess Tiantai (天台公主; 1605–1606), personal name Xuanmei (軒媺), tenth daughter

- Consort Xi, of the Wang clan (僖妃 王氏; d. 1589)

- Concubine De, of the Li clan (德嬪 李氏; 1567–1628)

- Princess Xianju (仙居公主; 1584–1585), personal name Xuanji (軒姞), fifth daughter

- Princess Taishun (泰順公主; d. 1593), personal name Xuanji (軒姬), eighth daughter

- Princess Xiangshan (香山公主; 1598–1599), personal name Xuandeng (軒嬁), ninth daughter

- Concubine Shen, of the Wei clan (慎嬪 魏氏; 1567–1606)

- Concubine Jing, of the Shao clan (敬嬪 邵氏; d. 1606)

- Concubine Shun, of the Zhang clan (順嬪 張氏; d. 1589)

- Concubine He, of the Liang clan (和嬪 梁氏; 1562–1643)

- Concubine Dao, of the Geng clan (悼嬪 耿氏; 1568–1589)

- Shiyu, of the Hu clan (侍御 胡氏)

- Noble Lady, of the Guo clan (貴人 郭氏)

Ancestry

| Chenghua Emperor (1447–1487) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaohui (d. 1522) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiajing Emperor (1507–1567) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiang Xiao | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Cixiaoxian (d. 1538) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Wu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Longqing Emperor (1537–1572) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Du Lin | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaoke (d. 1554) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Wanli Emperor (1563–1620) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Li Gang | |||||||||||||||||||

| Li Yu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Li Wei (1527–1583) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Dowager Xiaoding (1545–1614) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Wang | |||||||||||||||||||

Imperial regalia

See also

Notes

- ↑ Following the death of the emperor, the Wanli era was normally due to end on 21 January 1621. However, the Wanli Emperor's successor, the Taichang Emperor, died within a month, before 22 January 1621, which should have been the start of the Taichang era. The Tianqi Emperor, who succeeded the Taichang Emperor, decided that the Wanli era would be considered as having ended on the last day of the seventh month (equivalent to 27 August 1620), to enable the Taichang era to be applied retrospectively for the remaining five months in that year. Dates before 1582 are given in the Julian calendar, not in the proleptic Gregorian calendar. Dates after 1582 are given in the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ Xuyan, 虛言.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 727–. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- ↑ (Ming) Shen Defu (沈德符). Compilation of Wanli era catastrophes (萬曆野獲編), Volume 1: "又云世宗號堯齋,其後穆宗號舜齋,今上因之亦號禹齋,以故己卯『應天命禹』一題,乃暗頌兩朝,非諂江陵也。未知信否。"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Huang (1988), p. 514.

- 1 2 Swope (2008), p. 74.

- ↑ Duindam (2016), pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McMahon (2016), p. 127.

- 1 2 McMahon (2016), p. 128.

- ↑ Zheng (2005), pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 3 4 Huang (1988), p. 515.

- 1 2 3 "Zhang Juzheng". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Huang (1988), pp. 521–522.

- 1 2 Swope (2009), p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Swope (2008), p. 73.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 523.

- 1 2 3 4 Huang (1988), p. 525.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 526.

- ↑ Huang (1988), pp. 527–528.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 524.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 522.

- ↑ Swope (2008), p. 72.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 527.

- 1 2 3 Huang (1988), p. 537.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 528.

- 1 2 Swope (2009), p. 24.

- ↑ Pang (2015), p. 26–28.

- ↑ Swope (2008), p. 75.

- ↑ Luk (2016), pp. 70–77.

- 1 2 Zhao (2002), pp. 135–136.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), pp. 528–529.

- ↑ Zhao (2002), pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Zhao (2002), pp. 143–145.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 529.

- 1 2 3 Miller (2009), p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Huang (1988), p. 516.

- 1 2 3 Huang (1988), p. 517.

- 1 2 3 Huang (1988), p. 553.

- 1 2 3 Huang (1988), p. 554.

- ↑ Swope (2008), p. 82.

- ↑ Huang (1988), pp. 552–553.

- ↑ Jang (2008), p. 138.

- 1 2 Brook (2010), p. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 McMahon (2016), p. 130.

- ↑ Duindam (2016), pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Brook (2010), p. 102.

- ↑ McMahon (2016), pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 Dardess (2002), p. 9.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 550.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 517; 550.

- ↑ Dardess (2002), p. 10.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 555.

- ↑ Dardess (2002), p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Miller (2009), p. 75.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 530.

- 1 2 Miller (2009), p. 78.

- ↑ Miller (2009), p. 79.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 531.

- ↑ Miller (2009), p. 80.

- ↑ Von Glahn (1996), pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Miller (2009), p. 93.

- ↑ Miller (2009), p. 92.

- ↑ Miller (2009), pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Wei (2020), p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Wei (2020), p. 96.

- 1 2 Wei (2020), p. 95.

- 1 2 Wei (2020), p. 97.

- 1 2 Wei (2020), p. 98.

- ↑ Wei (2020), p. 99.

- ↑ "Donglin". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- 1 2 Cheng (2006), p. 522.

- 1 2 3 Elman (1989), p. 393.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 540.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 532.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 533.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 535.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 534.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 544.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 536.

- ↑ Fang (2014), pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 538.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 539.

- ↑ Huang (1988), pp. 539–540.

- ↑ Huang (1988), p. 541.

- ↑ Huang (1988), pp. 541–542.

- 1 2 Huang (1988), p. 543.

- ↑ Becker, Jasper (2008). City of Heavenly Tranquility: Beijing in the History of China. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530997-3, pp 77-79.

- ↑ "China's reluctant Emperor", The New York Times, Sheila Melvin, Sept. 7, 2011.

- ↑ Zheng Yangwen (2005). The Social Life of Opium in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-521-84608-0.

- ↑ "'징비록' 장태성-서윤아, 커플 대본 인증샷…'장난기 가득'". The Choson Ilbo (in Korean). 25 July 2020. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

Works cited

- Huang, Ray (1988). "The Lung-ch'ing and Wan-li reigns, 1567—1620". In Twitchett, Denis C; Mote, Frederick W. (eds.). The Cambridge History of China Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 511–584. ISBN 0521243335.

- Swope, Kenneth M (2008). "Bestowing the Double-edged Sword: Wanli as Supreme Military Commander". In Robinson, David M (ed.). Culture, Courtiers, and Competition: The Ming Court (1368–1644). Vol. 1. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 61–115. ISBN 0521243327.

- Duindam, Jeroen (2016). Dynasties: A Global History of Power, 1300-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-107-06068-0.

- McMahon, Keith (2016). Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442255029.

- Zheng, Yangwen (2005). The Social Life of Opium in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521846080.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (1996). Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (SUNY series in Chinese local studies ed.). New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791426874.

- Swope, Kenneth M (2009). A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598 (Campaigns and Commanders Series ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4056-8.

- Pang, Huiping (2015). "The Confiscating Henchmen: The Masquerade of Ming Embroidered-Uniform Guard Liu Shouyou (ca. 1540-1604)". Ming Studies. 72: 24–45. ISSN 0147-037X.

- Luk, Yu-ping (2016). "Heavenly Mistress and the Nine-lotus Bodhisattva: Visualizing the Celestial Identities of Two Empresses in Ming China (1368-1644)". In Bose, Melia Belli (ed.). Women, Gender and Art in Early Modern Asia, c. 1500-1900. London: Routledge/Ashgate. pp. 63–91.

- Zhao, Jie (2002). "A Decade of Considerable Significance: Late-Ming Factionalism in the Making, 1583-1593". T'oung Pao Second Series. 88 (1/3): 112–150.

- Miller, Harry (2009). State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572-1644. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61134-4.

- Jang, Scarlett (2008). "The Eunuch Agency Directorate of Ceremonial and the Ming Imperial Publishing Enterprise". In Robinson, David M (ed.). Culture, Courtiers, and Competition: The Ming Court (1368-1644). Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 116–185. ISBN 978-0-674-02823-4.

- Brook, Timothy (2010). The troubled empire: China in the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04602-3.

- Dardess, John W (2010). Blood and History in China: The Donglin Faction and Its Repression, 1620-1627. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824825164.

- Goodrich, L. Carington; Fang, Chaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644. Vol. II. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- Von Glahn, Richard (1996). Fountain of Fortune: money and monetary policy in China, 1000–1700. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20408-5.

- Wei, Yang (2020). "The paradoxical effect of autocracy: collective deliberation in the Ming official merit-evaluation system". In Swope, Kenneth M (ed.). The Ming world. Abington, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 88–101. ISBN 978-0-429-31871-9.

- Cheng, Anne (2006). Dějiny čínského myšlení (in Czech). Praha: DharmaGaia. ISBN 80-86685-52-7.

- Elman, Benjamin A (October 1989). "Imperial Politics and Confucian Societies in Late Imperial China: The Hanlin and Donglin Academies" (PDF). Modern China. 15 (4): 379–418.

- Fang, Jun (2014). China's Second Capital – Nanjing Under the Ming, 1368-1644 (1st ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9781135008451.

- Huang Ray, 1587, a Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981. ISBN 0300-025181