An ellipsoid is a surface that can be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a surface that may be defined as the zero set of a polynomial of degree two in three variables. Among quadric surfaces, an ellipsoid is characterized by either of the two following properties. Every planar cross section is either an ellipse, or is empty, or is reduced to a single point (this explains the name, meaning "ellipse-like"). It is bounded, which means that it may be enclosed in a sufficiently large sphere.

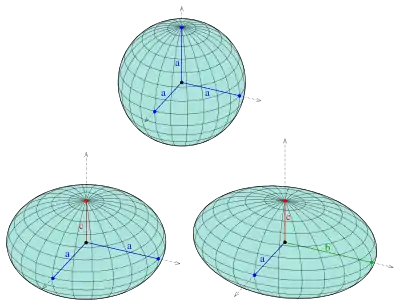

An ellipsoid has three pairwise perpendicular axes of symmetry which intersect at a center of symmetry, called the center of the ellipsoid. The line segments that are delimited on the axes of symmetry by the ellipsoid are called the principal axes, or simply axes of the ellipsoid. If the three axes have different lengths, the figure is a triaxial ellipsoid (rarely scalene ellipsoid), and the axes are uniquely defined.

If two of the axes have the same length, then the ellipsoid is an ellipsoid of revolution, also called a spheroid. In this case, the ellipsoid is invariant under a rotation around the third axis, and there are thus infinitely many ways of choosing the two perpendicular axes of the same length. If the third axis is shorter, the ellipsoid is an oblate spheroid; if it is longer, it is a prolate spheroid. If the three axes have the same length, the ellipsoid is a sphere.

Standard equation

The general ellipsoid, also known as triaxial ellipsoid, is a quadratic surface which is defined in Cartesian coordinates as:

where , and are the length of the semi-axes.

The points , and lie on the surface. The line segments from the origin to these points are called the principal semi-axes of the ellipsoid, because a, b, c are half the length of the principal axes. They correspond to the semi-major axis and semi-minor axis of an ellipse.

In spherical coordinate system for which , the general ellipsoid is defined as:

where is the polar angle and is the azimuthal angle.

When , the ellipsoid is a sphere.

When , the ellipsoid is a spheroid or ellipsoid of revolution. In particular, if , it is an oblate spheroid; if , it is a prolate spheroid.

Parameterization

The ellipsoid may be parameterized in several ways, which are simpler to express when the ellipsoid axes coincide with coordinate axes. A common choice is

where

These parameters may be interpreted as spherical coordinates, where θ is the polar angle and φ is the azimuth angle of the point (x, y, z) of the ellipsoid.[1]

Measuring from the equator rather than a pole,

where

θ is the reduced latitude, parametric latitude, or eccentric anomaly and λ is azimuth or longitude.

Measuring angles directly to the surface of the ellipsoid, not to the circumscribed sphere,

where

γ would be geocentric latitude on the Earth, and λ is longitude. These are true spherical coordinates with the origin at the center of the ellipsoid.

In geodesy, the geodetic latitude is most commonly used, as the angle between the vertical and the equatorial plane, defined for a biaxial ellipsoid. For a more general triaxial ellipsoid, see ellipsoidal latitude.

Volume

The volume bounded by the ellipsoid is

In terms of the principal diameters A, B, C (where A = 2a, B = 2b, C = 2c), the volume is

- .

This equation reduces to that of the volume of a sphere when all three elliptic radii are equal, and to that of an oblate or prolate spheroid when two of them are equal.

The volume of an ellipsoid is 2/3 the volume of a circumscribed elliptic cylinder, and π/6 the volume of the circumscribed box. The volumes of the inscribed and circumscribed boxes are respectively:

Surface area

The surface area of a general (triaxial) ellipsoid is[2][3]

where

and where F(φ, k) and E(φ, k) are incomplete elliptic integrals of the first and second kind respectively.[4] The surface area of this general ellipsoid can also be expressed using the RF and RD Carlson symmetric forms of the elliptic integrals by simply substituting the above formula to the respective definitions:

Unlike the expression with F(φ, k) and E(φ, k), the variant based on the Carlson symmetric integrals yields valid results for a sphere and only the axis c must be the smallest, the order between the two larger axes, a and b can be arbitrary.

The surface area of an ellipsoid of revolution (or spheroid) may be expressed in terms of elementary functions:

or

or

and

which, as follows from basic trigonometric identities, are equivalent expressions (i.e. the formula for Soblate can be used to calculate the surface area of a prolate ellipsoid and vice versa). In both cases e may again be identified as the eccentricity of the ellipse formed by the cross section through the symmetry axis. (See ellipse). Derivations of these results may be found in standard sources, for example Mathworld.[5]

Approximate formula

Here p ≈ 1.6075 yields a relative error of at most 1.061%;[6] a value of p = 8/5 = 1.6 is optimal for nearly spherical ellipsoids, with a relative error of at most 1.178%.

In the "flat" limit of c much smaller than a and b, the area is approximately 2πab, equivalent to p = log23 ≈ 1.5849625007.

Plane sections

The intersection of a plane and a sphere is a circle (or is reduced to a single point, or is empty). Any ellipsoid is the image of the unit sphere under some affine transformation, and any plane is the image of some other plane under the same transformation. So, because affine transformations map circles to ellipses, the intersection of a plane with an ellipsoid is an ellipse or a single point, or is empty.[7] Obviously, spheroids contain circles. This is also true, but less obvious, for triaxial ellipsoids (see Circular section).

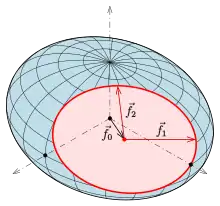

Determining the ellipse of a plane section

Given: Ellipsoid x2/a2 + y2/b2 + z2/c2 = 1 and the plane with equation nxx + nyy + nzz = d, which have an ellipse in common.

Wanted: Three vectors f0 (center) and f1, f2 (conjugate vectors), such that the ellipse can be represented by the parametric equation

(see ellipse).

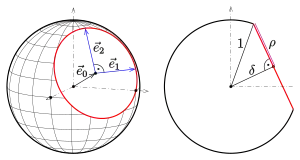

Solution: The scaling u = x/a, v = y/b, w = z/c transforms the ellipsoid onto the unit sphere u2 + v2 + w2 = 1 and the given plane onto the plane with equation

Let muu + mvv + mww = δ be the Hesse normal form of the new plane and

its unit normal vector. Hence

is the center of the intersection circle and

its radius (see diagram).

Where mw = ±1 (i.e. the plane is horizontal), let

Where mw ≠ ±1, let

In any case, the vectors e1, e2 are orthogonal, parallel to the intersection plane and have length ρ (radius of the circle). Hence the intersection circle can be described by the parametric equation

The reverse scaling (see above) transforms the unit sphere back to the ellipsoid and the vectors e0, e1, e2 are mapped onto vectors f0, f1, f2, which were wanted for the parametric representation of the intersection ellipse.

How to find the vertices and semi-axes of the ellipse is described in ellipse.

Example: The diagrams show an ellipsoid with the semi-axes a = 4, b = 5, c = 3 which is cut by the plane x + y + z = 5.

Pins-and-string construction

|S1 S2|, length of the string (red)

The pins-and-string construction of an ellipsoid is a transfer of the idea constructing an ellipse using two pins and a string (see diagram).

A pins-and-string construction of an ellipsoid of revolution is given by the pins-and-string construction of the rotated ellipse.

The construction of points of a triaxial ellipsoid is more complicated. First ideas are due to the Scottish physicist J. C. Maxwell (1868).[8] Main investigations and the extension to quadrics was done by the German mathematician O. Staude in 1882, 1886 and 1898.[9][10][11] The description of the pins-and-string construction of ellipsoids and hyperboloids is contained in the book Geometry and the imagination written by D. Hilbert & S. Vossen,[12] too.

Steps of the construction

- Choose an ellipse E and a hyperbola H, which are a pair of focal conics: with the vertices and foci of the ellipseand a string (in diagram red) of length l.

- Pin one end of the string to vertex S1 and the other to focus F2. The string is kept tight at a point P with positive y- and z-coordinates, such that the string runs from S1 to P behind the upper part of the hyperbola (see diagram) and is free to slide on the hyperbola. The part of the string from P to F2 runs and slides in front of the ellipse. The string runs through that point of the hyperbola, for which the distance |S1 P| over any hyperbola point is at a minimum. The analogous statement on the second part of the string and the ellipse has to be true, too.

- Then: P is a point of the ellipsoid with equation

- The remaining points of the ellipsoid can be constructed by suitable changes of the string at the focal conics.

Semi-axes

Equations for the semi-axes of the generated ellipsoid can be derived by special choices for point P:

The lower part of the diagram shows that F1 and F2 are the foci of the ellipse in the xy-plane, too. Hence, it is confocal to the given ellipse and the length of the string is l = 2rx + (a − c). Solving for rx yields rx = 1/2(l − a + c); furthermore r2

y = r2

x − c2.

From the upper diagram we see that S1 and S2 are the foci of the ellipse section of the ellipsoid in the xz-plane and that r2

z = r2

x − a2.

Converse

If, conversely, a triaxial ellipsoid is given by its equation, then from the equations in step 3 one can derive the parameters a, b, l for a pins-and-string construction.

Confocal ellipsoids

If E is an ellipsoid confocal to E with the squares of its semi-axes

then from the equations of E

one finds, that the corresponding focal conics used for the pins-and-string construction have the same semi-axes a, b, c as ellipsoid E. Therefore (analogously to the foci of an ellipse) one considers the focal conics of a triaxial ellipsoid as the (infinite many) foci and calls them the focal curves of the ellipsoid.[13]

The converse statement is true, too: if one chooses a second string of length l and defines

then the equations

are valid, which means the two ellipsoids are confocal.

Limit case, ellipsoid of revolution

In case of a = c (a spheroid) one gets S1 = F1 and S2 = F2, which means that the focal ellipse degenerates to a line segment and the focal hyperbola collapses to two infinite line segments on the x-axis. The ellipsoid is rotationally symmetric around the x-axis and

- .

Properties of the focal hyperbola

Bottom: parallel and central projection of the ellipsoid such that it looks like a sphere, i.e. its apparent shape is a circle

- True curve

- If one views an ellipsoid from an external point V of its focal hyperbola, than it seems to be a sphere, that is its apparent shape is a circle. Equivalently, the tangents of the ellipsoid containing point V are the lines of a circular cone, whose axis of rotation is the tangent line of the hyperbola at V.[14][15] If one allows the center V to disappear into infinity, one gets an orthogonal parallel projection with the corresponding asymptote of the focal hyperbola as its direction. The true curve of shape (tangent points) on the ellipsoid is not a circle. The lower part of the diagram shows on the left a parallel projection of an ellipsoid (with semi-axes 60, 40, 30) along an asymptote and on the right a central projection with center V and main point H on the tangent of the hyperbola at point V. (H is the foot of the perpendicular from V onto the image plane.) For both projections the apparent shape is a circle. In the parallel case the image of the origin O is the circle's center; in the central case main point H is the center.

- Umbilical points

- The focal hyperbola intersects the ellipsoid at its four umbilical points.[16]

Property of the focal ellipse

The focal ellipse together with its inner part can be considered as the limit surface (an infinitely thin ellipsoid) of the pencil of confocal ellipsoids determined by a, b for rz → 0. For the limit case one gets

In general position

As a quadric

If v is a point and A is a real, symmetric, positive-definite matrix, then the set of points x that satisfy the equation

is an ellipsoid centered at v. The eigenvectors of A are the principal axes of the ellipsoid, and the eigenvalues of A are the reciprocals of the squares of the semi-axes: a−2, b−2 and c−2.[17]

An invertible linear transformation applied to a sphere produces an ellipsoid, which can be brought into the above standard form by a suitable rotation, a consequence of the polar decomposition (also, see spectral theorem). If the linear transformation is represented by a symmetric 3 × 3 matrix, then the eigenvectors of the matrix are orthogonal (due to the spectral theorem) and represent the directions of the axes of the ellipsoid; the lengths of the semi-axes are computed from the eigenvalues. The singular value decomposition and polar decomposition are matrix decompositions closely related to these geometric observations.

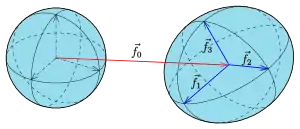

Parametric representation

The key to a parametric representation of an ellipsoid in general position is the alternative definition:

- An ellipsoid is an affine image of the unit sphere.

An affine transformation can be represented by a translation with a vector f0 and a regular 3 × 3 matrix A:

where f1, f2, f3 are the column vectors of matrix A.

A parametric representation of an ellipsoid in general position can be obtained by the parametric representation of a unit sphere (see above) and an affine transformation:

- .

If the vectors f1, f2, f3 form an orthogonal system, the six points with vectors f0 ± f1,2,3 are the vertices of the ellipsoid and |f1|, |f2|, |f3| are the semi-principal axes.

A surface normal vector at point x(θ, φ) is

For any ellipsoid there exists an implicit representation F(x, y, z) = 0. If for simplicity the center of the ellipsoid is the origin, f0 = 0, the following equation describes the ellipsoid above:[18]

Applications

The ellipsoidal shape finds many practical applications:

- Earth ellipsoid, a mathematical figure approximating the shape of the Earth.

- Reference ellipsoid, a mathematical figure approximating the shape of planetary bodies in general.

- Poinsot's ellipsoid, a geometrical method for visualizing the torque-free motion of a rotating rigid body.

- Lamé's stress ellipsoid, an alternative to Mohr's circle for the graphical representation of the stress state at a point.

- Manipulability ellipsoid, used to describe a robot's freedom of motion.

- Jacobi ellipsoid, a triaxial ellipsoid formed by a rotating fluid

- Index ellipsoid, a diagram of an ellipsoid that depicts the orientation and relative magnitude of refractive indices in a crystal.

- Thermal ellipsoid, ellipsoids used in crystallography to indicate the magnitudes and directions of the thermal vibration of atoms in crystal structures.

- Lighting

- Medicine

- Measurements obtained from MRI imaging of the prostate can be used to determine the volume of the gland using the approximation L × W × H × 0.52 (where 0.52 is an approximation for π/6)[19]

Dynamical properties

The mass of an ellipsoid of uniform density ρ is

The moments of inertia of an ellipsoid of uniform density are

For a = b = c these moments of inertia reduce to those for a sphere of uniform density.

Ellipsoids and cuboids rotate stably along their major or minor axes, but not along their median axis. This can be seen experimentally by throwing an eraser with some spin. In addition, moment of inertia considerations mean that rotation along the major axis is more easily perturbed than rotation along the minor axis.[20]

One practical effect of this is that scalene astronomical bodies such as Haumea generally rotate along their minor axes (as does Earth, which is merely oblate); in addition, because of tidal locking, moons in synchronous orbit such as Mimas orbit with their major axis aligned radially to their planet.

A spinning body of homogeneous self-gravitating fluid will assume the form of either a Maclaurin spheroid (oblate spheroid) or Jacobi ellipsoid (scalene ellipsoid) when in hydrostatic equilibrium, and for moderate rates of rotation. At faster rotations, non-ellipsoidal piriform or oviform shapes can be expected, but these are not stable.

Fluid dynamics

The ellipsoid is the most general shape for which it has been possible to calculate the creeping flow of fluid around the solid shape. The calculations include the force required to translate through a fluid and to rotate within it. Applications include determining the size and shape of large molecules, the sinking rate of small particles, and the swimming abilities of microorganisms.[21]

In probability and statistics

The elliptical distributions, which generalize the multivariate normal distribution and are used in finance, can be defined in terms of their density functions. When they exist, the density functions f have the structure:

where k is a scale factor, x is an n-dimensional random row vector with median vector μ (which is also the mean vector if the latter exists), Σ is a positive definite matrix which is proportional to the covariance matrix if the latter exists, and g is a function mapping from the non-negative reals to the non-negative reals giving a finite area under the curve.[22] The multivariate normal distribution is the special case in which g(z) = exp(−z/2) for quadratic form z.

Thus the density function is a scalar-to-scalar transformation of a quadric expression. Moreover, the equation for any iso-density surface states that the quadric expression equals some constant specific to that value of the density, and the iso-density surface is an ellipsoid.

In higher dimensions

A hyperellipsoid, or ellipsoid of dimension in a Euclidean space of dimension , is a quadric hypersurface defined by a polynomial of degree two that has a homogeneous part of degree two which is a positive definite quadratic form.

One can also define a hyperellipsoid as the image of a sphere under an invertible affine transformation. The spectral theorem can again be used to obtain a standard equation of the form

The volume of an n-dimensional hyperellipsoid can be obtained by replacing Rn by the product of the semi-axes a1a2...an in the formula for the volume of a hypersphere:

(where Γ is the gamma function).

See also

- Ellipsoidal dome

- Ellipsoid method

- Ellipsoidal coordinates

- Elliptical distribution, in statistics

- Flattening, also called ellipticity and oblateness, is a measure of the compression of a circle or sphere along a diameter to form an ellipse or an ellipsoid of revolution (spheroid), respectively.

- Focaloid, a shell bounded by two concentric, confocal ellipsoids

- Geodesics on an ellipsoid

- Geodetic datum, the gravitational Earth modeled by a best-fitted ellipsoid

- Homoeoid, a shell bounded by two concentric similar ellipsoids

- List of surfaces

- Superellipsoid

Notes

- ↑ Kreyszig (1972, pp. 455–456)

- ↑ F.W.J. Olver, D.W. Lozier, R.F. Boisvert, and C.W. Clark, editors, 2010, NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions (Cambridge University Press), available online at "DLMF: 19.33 Triaxial Ellipsoids". Archived from the original on 2012-12-02. Retrieved 2012-01-08. (see next reference).

- ↑ NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) at http://www.nist.gov Archived 2015-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "DLMF: 19.2 Definitions".

- ↑ W., Weisstein, Eric. "Prolate Spheroid". mathworld.wolfram.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Final answers Archived 2011-09-30 at the Wayback Machine by Gerard P. Michon (2004-05-13). See Thomsen's formulas and Cantrell's comments.

- ↑ Albert, Abraham Adrian (2016) [1949], Solid Analytic Geometry, Dover, p. 117, ISBN 978-0-486-81026-3

- ↑ W. Böhm: Die FadenKonstruktion der Flächen zweiter Ordnung, Mathemat. Nachrichten 13, 1955, S. 151

- ↑ Staude, O.: Ueber Fadenconstructionen des Ellipsoides. Math. Ann. 20, 147–184 (1882)

- ↑ Staude, O.: Ueber neue Focaleigenschaften der Flächen 2. Grades. Math. Ann. 27, 253–271 (1886).

- ↑ Staude, O.: Die algebraischen Grundlagen der Focaleigenschaften der Flächen 2. Ordnung Math. Ann. 50, 398 - 428 (1898).

- ↑ D. Hilbert & S Cohn-Vossen: Geometry and the imagination, Chelsea New York, 1952, ISBN 0-8284-1087-9, p. 20 .

- ↑ O. Hesse: Analytische Geometrie des Raumes, Teubner, Leipzig 1861, p. 287

- ↑ D. Hilbert & S Cohn-Vossen: Geometry and the Imagination, p. 24

- ↑ O. Hesse: Analytische Geometrie des Raumes, p. 301

- ↑ W. Blaschke: Analytische Geometrie, p. 125

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-26. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) pp. 17–18. - ↑ Computerunterstützte Darstellende und Konstruktive Geometrie. Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine Uni Darmstadt (PDF; 3,4 MB), S. 88.

- ↑ Bezinque, Adam; et al. (2018). "Determination of Prostate Volume: A Comparison of Contemporary Methods". Academic Radiology. 25 (12): 1582–1587. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2018.03.014. PMID 29609953. S2CID 4621745.

- ↑ Goldstein, H G (1980). Classical Mechanics, (2nd edition) Chapter 5.

- ↑ Dusenbery, David B. (2009).Living at Micro Scale, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ↑ Frahm, G., Junker, M., & Szimayer, A. (2003). Elliptical copulas: applicability and limitations. Statistics & Probability Letters, 63(3), 275–286.

References

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-50728-8

External links

- "Ellipsoid" by Jeff Bryant, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Ellipsoid and Quadratic Surface, MathWorld.