| Lymphatic vessel | |

|---|---|

Lymph capillaries in the tissue spaces. | |

The thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct. | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vas lymphaticum |

| MeSH | D042601 |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.038 |

| TA2 | 3915 |

| TH | H3.09.02.0.05001 |

| FMA | 30315 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The lymphatic vessels (or lymph vessels or lymphatics) are thin-walled vessels (tubes), structured like blood vessels, that carry lymph. As part of the lymphatic system, lymph vessels are complementary to the cardiovascular system. Lymph vessels are lined by endothelial cells, and have a thin layer of smooth muscle, and adventitia that binds the lymph vessels to the surrounding tissue. Lymph vessels are devoted to the propulsion of the lymph from the lymph capillaries, which are mainly concerned with the absorption of interstitial fluid from the tissues. Lymph capillaries are slightly bigger than their counterpart capillaries of the vascular system. Lymph vessels that carry lymph to a lymph node are called afferent lymph vessels, and those that carry it from a lymph node are called efferent lymph vessels, from where the lymph may travel to another lymph node, may be returned to a vein, or may travel to a larger lymph duct. Lymph ducts drain the lymph into one of the subclavian veins and thus return it to general circulation.

The vessels that bring lymph away from the tissues and towards the lymph nodes can be classified as afferent vessels. These afferent vessels then drain into the subcapsular sinus.[1] The efferent vessels that bring lymph from the lymphatic organs to the nodes bringing the lymph to the right lymphatic duct or the thoracic duct, the largest lymph vessel in the body. These vessels drain into the right and left subclavian veins, respectively. There are far more afferent vessels bringing in lymph than efferent vessels taking it out to allow for lymphocytes and macrophages to fulfill their immune support functions. The lymphatic vessels contain valves.

Structure

The general structure of lymphatics is based on that of blood vessels. There is an inner lining of single flattened epithelial cells (simple squamous epithelium) composed of a type of epithelium that is called the endothelium, and the cells are called endothelial cells. This layer functions to mechanically transport fluid and since the basement membrane on which it rests is discontinuous; it leaks easily.[2] The next layer is that of smooth muscles that are arranged in a circular fashion around the endothelium, which by shortening (contracting) or relaxing alter the diameter (caliber) of the lumen. The outermost layer is the adventitia which consists of fibrous tissue. The general structure described here is seen only in larger lymphatics; smaller lymphatics have fewer layers. The smallest vessels (lymphatic or lymph capillaries) lack both the muscular layer and the outer adventitia. As they proceed forward and in their course are joined by other capillaries, they grow larger and first take on an adventitia, and then smooth muscles.

The lymphatic conducting system broadly consists of two types of channels—the initial lymphatics, the prelymphatics or lymph capillaries that specialize in collection of the lymph from the interstital fluid, and the larger lymph vessels that propel the lymph forward.

Unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system is not closed and has no central pump. Lymph movement occurs despite low pressure due to peristalsis (propulsion of the lymph due to alternate contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle), valves, and compression during contraction of adjacent skeletal muscle and arterial pulsation.[3]

Lymph capillaries

The lymphatic circulation begins with blind ending (closed at one end) highly permeable superficial lymph capillaries, formed by endothelial cells with button-like junctions between them that allow fluid to pass through them when the interstitial pressure is sufficiently high.[4] These button-like junctions consist of protein filaments like platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, or PECAM-1. A valve system in place here prevents the absorbed lymph from leaking back into the interstital fluid. This valve system involves collagen fibers attached to lymphatic endothelial cells that respond to increased interstitial fluid pressure by separating the endothelial cells and allowing the flow of lymph into the capillary for circulation.[5] There is another system of semilunar valves that prevents back-flow of lymph along the lumen of the vessel.[4] Lymph capillaries have many interconnections (anastomoses) between them and form a very fine network.[6]

Rhythmic contraction of the vessel walls through movements may also help draw fluid into the smallest lymphatic vessels, capillaries. If tissue fluid builds up the tissue will swell; this is called edema. As the circular path through the body's system continues, the fluid is then transported to progressively larger lymphatic vessels culminating in the right lymphatic duct (for lymph from the right upper body) and the thoracic duct (for the rest of the body); both ducts drain into the circulatory system at the right and left subclavian veins. The system collaborates with white blood cells in lymph nodes to protect the body from being infected by cancer cells, fungi, viruses or bacteria. This is known as a secondary circulatory system.

Lymph vessels

The lymph capillaries drain into larger collecting lymphatics. These are contractile lymphatics which transport lymph using a combination of smooth muscle walls, which contract to assist in transporting lymph, as well as valves to prevent the lymph from flowing backwards.[3] As the collecting lymph vessel accumulates lymph from more and more lymph capillaries along its length, it becomes larger and eventually becomes an afferent lymph vessel as it enters a lymphs node. The lymph percolates through the lymph node tissue and exits via an efferent lymph vessel. An efferent lymph vessel may directly drain into one of the (right or thoracic) lymph ducts, or may empty into another lymph node as its afferent lymph vessel.[6] Both the lymph ducts return the lymph to the blood stream by emptying into the subclavian veins

Lymph vessels consist of functional units known as lymphangions which are segments separated by semilunar valves. These segments propel or resist the flow of lymph by the contraction of the encircling smooth muscle depending upon the ratio of its length to its radius.[7]

Function

Lymph vessels act as reservoirs for plasma and other substances including cells that have leaked from the vascular system and transport lymph fluid back from the tissues to the circulatory system. Without functioning lymph vessels, lymph cannot be effectively drained and lymphedema typically results.

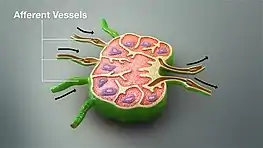

Afferent vessels

The afferent lymph vessels enter at all parts of the periphery of the lymph node, and after branching and forming a dense plexus in the substance of the capsule, open into the lymph sinuses of the cortical part. It carries unfiltered lymph into the node. In doing this they lose all their coats except their endothelial lining, which is continuous with a layer of similar cells lining the lymph paths.

Afferent lymphatic vessels are only found in lymph nodes. This is in contrast to efferent lymphatic vessel which are also found in the thymus and spleen.

Efferent vessels

The efferent lymphatic vessel commences from the lymph sinuses of the medullary portion of the lymph nodes and leave the lymph nodes at the hilum, either to veins or greater nodes. It carries filtered lymph out of the node.

Efferent lymphatic vessels are also found in association with the thymus and spleen. This is in contrast to afferent lymphatic vessels, which are found only in association with lymph nodes.

Clinical significance

Lymphedema is the swelling of tissues due to insufficient fluid drainage by the lymphatic vessels. It can be the result from absent, underdeveloped or dysfunctional lymphatic vessels. In hereditary (or primary) lymphedema, the lymphatic vessels are absent, underdeveloped or dysfunctional due to genetic causes. In acquired (or secondary) lymphedema, the lymphatic vessels are damaged by injury or infection.[8][9] Lymphangiomatosis is a disease involving multiple cysts or lesions formed from lymphatic vessels.

See also

Additional images

Lymphatic system

Lymphatic system Section across portal canal of pig. X 250.

Section across portal canal of pig. X 250.

References

- ↑ "19.2B: Distribution of Lymphatic Vessels". Medicine LibreTexts. 22 July 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ↑ Pepper MS, Skobe M (October 2003). "Lymphatic endothelium: morphological, molecular and functional properties". The Journal of Cell Biology. 163 (2): 209–13. doi:10.1083/jcb.200308082. PMC 2173536. PMID 14581448.

- 1 2 Shayan R, Achen MG, Stacker SA (September 2006). "Lymphatic vessels in cancer metastasis: bridging the gaps". Carcinogenesis. 27 (9): 1729–38. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl031. PMID 16597644.

- 1 2 Baluk P, Fuxe J, Hashizume H, Romano T, Lashnits E, Butz S, et al. (October 2007). "Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 204 (10): 2349–62. doi:10.1084/jem.20062596. PMC 2118470. PMID 17846148.

- ↑ Weitman E, Cuzzone D, Mehrara BJ (September 2013). "Tissue engineering and regeneration of lymphatic structures". Future Oncology. 9 (9): 1365–74. doi:10.2217/fon.13.110. PMC 4095806. PMID 23980683.

- 1 2 Rosse C, Gaddum-Rosse P (1997). "The Cardiovascular System (Chapter 8)". Hollinshead's Textbook of Anatomy (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-397-51256-2.

- ↑ Venugopal AM, Stewart RH, Rajagopalan S, Laine GA, Quick CM (2004). "Optimal Lymphatic Vessel Structure". The 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE. Vol. 2. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. pp. 3700–3703. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1404039. ISBN 0-7803-8439-3.

- ↑ Alitalo K (November 2011). "The lymphatic vasculature in disease". Nature Medicine. 17 (11): 1371–80. doi:10.1038/nm.2545. PMID 22064427. S2CID 5899689.

- ↑ Krebs R, Jeltsch M (2013). "The lymphangiogenic growth factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D. Part 2: The role of VEGF-C and VEGF-D in lymphatic system diseases". Lymphologie in Forschung und Praxis. 17 (2): 96–104.

Further reading

- Nosek TM. "Role of Lymphatic Vessels". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

External links

- Lymphatic+Vessels at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Efferent lymph vessel - BioWeb at University of Wisconsin System