| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Eastern Orthodoxy arrived in the areas of Illyrii proprie dicti or Principality of Arbanon during the period of Byzantine Empire. Those areas fell under the Ottoman Empire during the late medieval times and Eastern Orthodoxy underwent deep sociopolitical difficulties that lasted until the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Between 1913 and until the start of WWII under the newly recognized state of Albania, Eastern Orthodoxy saw a revival and in the 1937 the Autocephaly after a short Eastern Orthodoxy schism and contestation was recognized. Decades of persecution under the Communist state atheism, which started in 1967 and officially ended in December 1990, greatly weakened all religions and their practices especially Christians of Albania. The post-communist period and the lifting of legal and other government restrictions on religion allowed Orthodoxy to revive through institutions and enabled the development of new infrastructure, literature, educational facilities, international transnational links and other social activities.

History

Christianity first arrived in the areas of the Principality of Arbanon through the preachings of Saint Paul during the 1st century. Saint Paul wrote that he preached in the Roman province of Illyricum,[1] and legend holds that he visited Dyrrachium.[2] It was Saint Astius, a 2nd-century Illyrian and Christian martyr venerated by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, that served as bishop of Durrës (Dyrrachium), during the time of the emperor Trajan (98–117). Astius is the Patron Saint and Protector of Durrës. However it was Roman emperor of Illyrian origins, Constantine the Great, who issued the Edict of Milan and legalized Christianity, that the Christian religion became official to what is considered today Albania.[3] Modern scholars argue that there is not sufficient evidence to suggest that the historical Illyricum, a province of the Roman Empire of the first century AD, which never officially adapted the Christian faith has any cultural, religious, linguistic or historical connection with the areas that were Principality of Arbanon attested by ancient Roman writers Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela as Illyrii proprie dicti.

The schism of 1054, however, formalized the split of Christianity into two branches, Roman Catholics and Orthodox Catholics, that was reflected in areas of the Principality of Arbanon with the emergence of Roman Catholics in the northwest and Orthodox Catholics in the northeast and the south.[4] In the 11th century, the Roman Catholic church created the archbishopric in Bar, that brought the bishoprics of Drivast, Ulcinj, Shkodër, and others under its control.[4] After the west-east schism the northwestern areas of Principality of Arbanon joined or became Roman Catholics while the northeast and the south remained Eastern Orthodox or Orthodox Catholics. As such during the latter half of 12th century Roman Catholicism spread in northwestern Albania and in northeastern and southern Albania partially made inroads among the population.[4] When the Ottoman Empire become the dominating force in those areas it exploited through intrigues the east-west schism to the maximum extent possible which lead to deep bitternes between the Roman Catholics and Orthodox and continue to occur even in the 21st century. The religious transition from Orthodoxy to Catholicism occurred during or before the schism, and due to close relations with the bishop of Rome only a few Roman Catholics converted to Islam during the Ottoman occupation in northewestern Albania, but the majority of Orthodox beliveres of northeast and south of Albania of that time due to lack of national identity, back then, converted to Islam using conversion as a means of resisting pressures arising from geopolitical factors such as Orthodox Serbs. The Orthodox Albanians who identidifed with Greek or Hellenes remained Orthodox.[5][6] During the moment of schism (1054) Albanians were attached to the Eastern Orthodox Church and were all Orthodox Christians in the northeast and south of today's twenty first century Albania or medieval Principality of Arbanon, while the majority of northwesterns became and remained Roman Catholic.[4][5]

Orthodoxy during the Ottoman Period

The official Ottoman recognition of the Orthodox church resulted in the Orthodox population being tolerated until the late 18th century and the traditionalism of the church's institutions slowed the process of conversion to Islam amongst Albanians.[7][8][9] The Orthodox population of central and south-eastern Albania was under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid, while south-western Albania was under the Patriarchate of Constantinople through the Metropolis of Ioannina.[10][11] In the early 16th century the Albanian cities of Gjirokastër, Kaninë, Delvinë, Vlorë, Korçë, Këlcyrë, Përmet and Berat were still Christian and by the late 16th century Vlorë, Përmet and Himarë were still Christian, while Gjirokastër increasingly became Muslim.[10][12] Conversion to Islam in cities overall within Albania was slow during the 16th century as around only 38% of the urban population had become Muslim.[12][13] The city of Berat from 1670 onward became mainly Muslim and its conversion is attributed in part to a lack of Christian priests being able to provide religious services.[14]

Differences between Christian Albanians of central Albania and archbishops of Ohrid led to conversions to Bektashi Islam that made an appeal to all while insisting little on ritual observance.[15] Central Albania, such as the Durrës area had by end of the 16th century become mainly Muslim.[12] Consisting of plains and being an in between area of northern and southern Albania, central Albania was a hub on the old Via Egnatia road that linked commercial, cultural and transport connections which were subject to direct Ottoman administrative control and religious Muslim influence.[16][17] The conversion to Islam of most of central Albania has thus been attributed in large part to the role its geography played in the socio-political and economic fortunes of the region.[16][17]

During the late eighteenth century Orthodox Albanians converted in large numbers to Islam due overwhelmingly to the Russo-Turkish wars of the period and events like the Russian instigated Orlov revolt (1770) that made the Ottomans view the Orthodox population as allies of Russia.[8][14][18][19] As some Orthodox Albanians rebelled against the Ottoman Empire, the Porte responded with and at times applied force to convert Orthodox Albanians to Islam while also providing economic measures to stimulate religious conversion.[8][14][19][20] During this time conflict between newly converted Muslim Albanians and Orthodox Albanians occurred in certain areas. Examples include the coastal villages of Borsh attacking Piqeras in 1744, making some flee abroad to places such as southern Italy.[21][22] Other areas such as 36 villages north of the Pogoni area converted in 1760 and followed it up with an attack on Orthodox Christian villages of the Kolonjë, Leskovik and Përmet areas leaving many settlements sacked and ruined.[22]

By the late eighteenth century socio-political and economic crises alongside nominal Ottoman government control resulted in local banditry and Muslim Albanian bands raided Aromanian, Greek and Orthodox Albanian settlements located today within and outside contemporary Albania.[23][24][25][26] Within Albania those raids culminated in Vithkuq, mainly an Orthodox Albanian centre, Moscopole (Albanian: Voskopojë) mainly an Aromanian centre, both with Greek literary, educational and religious culture and other smaller settlements being destroyed.[8][20][24][25][26] Those events pushed some Aromanians and Orthodox Albanians to migrate afar to places such as Macedonia, Thrace and so on.[8][20][24][25][26][27] Some Orthodox individuals, known as neo-martyrs, attempted to stem the tide of conversion to Islam amongst the Orthodox Albanian population and were executed in the process.[28] Notable among these individuals was Cosmas of Aetolia, (died 1779) a Greek monk and missionary who traveled and preached afar as Krujë, opened many Greek schools before being accused as a Russian agent and executed by Ottoman Muslim Albanian authorities.[29] Cosmas advocated for Greek education and spread of Greek language among illiterate Christian non-Greek speaking peoples so that they could understand the scriptures, liturgy and thereby remain Orthodox while his spiritual message is revered among contemporary Orthodox Albanians.[29][30][31] By 1798 a massacre perpetrated against the coastal Orthodox Albanian villages of Shënvasil and Nivicë-Bubar by Ali Pasha, semi-independent ruler of the Pashalik of Yanina led to another sizable wave of conversions of Orthodox Albanians to Islam.[8][18]

Other conversions such as those in the region of Labëria occurred due to ecclesiastical matters when for example during a famine the local Orthodox bishop refused to grant a break in the fast to consume milk with threats of hell.[32] Conversion to Islam also was undertaken for economic reasons which offered a way out of heavy taxation such as the jizya or poll tax and other difficult Ottoman measures imposed on Christians while opening up opportunities such as wealth accumulation and so on.[7][32][33] Other multiple factors that led to conversions to Islam were the poverty of the Church, illiterate clergy, a lack of clergy in some areas and worship in a language other than Albanian.[7][14][17][32] Additionally the reliance of the bishoprics of Durrës and southern Albania upon the declining Archbishopric of Ohrid, due in part to simony weakened the ability of Orthodox Albanians in resisting conversion to Islam.[14][17] Crypto-Christianity also occurred in certain instances throughout Albania in regions such as Shpat amongst populations that had recently converted from Orthodoxy to Islam.[34][35][7][28][36] Gorë, a borderland region straddling contemporary north-eastern Albania and southern Kosovo, had a Slavic Orthodox population which converted to Islam during the latter half of the eighteenth century due to the abolition of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć (1766) and subsequent unstable ecclesiastical structures.[37]

By the mid-19th century, because of the Tanzimat reforms started in 1839, which imposed mandatory military service on non-Muslims, the Orthodox Church lost adherents as the majority of Albanians had become Muslim.

Establishment of an authocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church

After Albanian independence in 1912, Noli (who in 1924 would also be a political figure and prime minister of Albania), traveled to Albania where he played an important role in establishing the Orthodox Albanian Church.[38] On September 17, 1922, the first Orthodox Congress convened at Berat formally laid the foundations of an Albanian Orthodox Church and declared its autocephaly.[39][40] The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople recognized the independence or autocephaly of the Orthodox Albanian Church in 1937.[39]

Persecution of Orthodoxy under Communism

Hohxa propagated that Albania is threatened by religion in general, since it serves the "Trojan Horse" style interests of the country's traditional enemies; in particular Orthodoxy those of Greece and Serbia.[41] In 1952 Archbishop Kristofor was discovered dead; most believed he had been killed.

In 1967 Hoxha closed down all churches and mosques in the country, and declared Albania the world's first atheist country. All expression of religion, public or private, was outlawed. Hundreds of priests and imams were killed or imprisoned.

Eastern Orthodoxy in Post-Communist Albania

In December 1990, Communist officials officially ended the 23 year long religious ban in Albania. Only 22 Orthodox priests remained alive. To deal with this situation, the Ecumenical Patriarch appointed Anastasios to be the Patriarchal Exarch for the Albanian Church. As Bishop of Androusa, Anastasios was dividing his time between his teaching duties at the University of Athens and the Archbishopric of Irinoupolis in Kenya, which was then going through a difficult patch, before his appointment. He was elected on June 24, 1992 and enthroned on August 2, 1992.[42] Over time Anastasios has gained respect for his charity work and is now recognized as a spiritual leader of the Orthodox Church in Albania.

In 1992, Anastasios would use a disused hotel for initial liturgy services in Durrës. As of February 2011, there were 145 clergy members, all of which were Albanian citizens who graduated from the Resurrection of Christ Theological Academy. This academy is also preparing new members (men and women) for catechism and for other services in different Church activities.

Anastas’ domestic activities in Albania include the reconstruction of various Orthodox Churches which were confiscated by the communist authorities, the rebuilding of 150 churches, and the additional investments into schools & charities for the poor.

Another major introduction by Anastas was the Ngjalla radio station which preaches spiritual, educational, musical, and informative information about the religion.[43]

During 1999, when Albania accepted waves of refugees from Kosovo, the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania, in collaboration with donors and other international religious organizations (especially ACT and WCC), led an extensive humanitarian program of more than $12 million, hosting 33,000 Kosovars in its two camps, supplying them with food, clothes, medical care and other goods.

Apart from the two ecclesiastical high schools, it has established three elementary schools (1st – 9th grade), 17 day-care centers and two institutes for professional training (named "Spirit of Love", established in Tirana in 2000) which are said to be the first of their kind in Albania and provide education in the fields of Team Management, IT Accounting, Computer Science, Medical Laboratory, Restoration and Conservation of Artwork and Byzantine Iconography.[43] In Gjirokastër, 1 professional school, the orphanage “The Orthodox Home of Hope”, a high school dormitory for girls, has also given technical and material support to many public schools.

An Office of Cultural Heritage was established to look after the Orthodox structures considered to be national cultural monuments. A number of choirs have been organized in the churches. A Byzantine choir has also been formed and has produced cassettes and CDs. A workshop for the restoration and painting of icons was established with the aim to train a new generation of artists, to revive the rich tradition of iconography. The Church has also sponsored important academic publications, documentary films, academic symposiums and various exhibits of iconography, codex, children’s projects and other culturally related themes.

The Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania actively participates as equals in the events of the Orthodox Church worldwide. It is a member of the Conference of the European Churches (of which the Archbishop Anastasios has served as vice-president since December 2003), the World Council of the Churches (of which Archbishop Anastasios was chosen as one of eight presidents in 2006), and the largest inter-faith organization in the world, "Religions for Peace" (of which Anastasios was chosen as Honorary President in 2006). It is also active in various ecumenical conferences and programs. The Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania contributes to the efforts for peaceful collaboration and solidarity in the region and beyond.

Controversies

Demolition and confiscation by state authorities

In August 2013, demonstrations took place[44] by the Orthodox community of Përmet as a result of the confiscation of the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin and the forcible removal of the clergy and of religious artifacts from the temple, by the state authorities.[45][46] The Cathedral was allegedly not fully returned to the Orthodox Albania after the restoration of Democracy in the country.[47] The incident provoked reactions by the Orthodox Church of Albania and also triggered diplomatic intervention from Greece.[46][48]

Individuals

There is a widespread belief that the Orthodox faith is linked with conspiracy theories in which the identification with Greek expansionist plans would classify them as potential enemies of the state.[49]

In early 2014 in a trip to the US, Archbishop Anastasios was met by protestors from the Albanian diaspora who oppose his position as head of the church due to him being from Greece.[50] Whereas due to the Albanian Orthodox Church head and some bishops being from Greece, Fatos Klosi, former head of Albanian intelligence stated in an April 2014 media interview that the Albanian Orthodox Church is Greek controlled and no longer an Albanian institution.[51] Klosi's comments were seen in Albania as controversial, rebuked by the church while it also sparked media discussion at the time.[52][53][54]

The Albanian Orthodox Church created a new diocese in Elbasan on April 17, 2016.[55] Its creation is opposed by Father Nikolla Marku who runs the local St Mary's church and who has broken ties with the Albanian Orthodox Church in the 1990s.[55] The dispute has been ongoing as the Albanian Orthodox Church views Marku's tenure over the church as illegal.[55] Marku's differences with the Orthodox church relate mainly to Anastasios Yannoulatos' being a Greek citizen heading the church in Albania with allegations that it has promoted divisions amongst the Orthodox community and Greek "chauvinism".[55] Marku as a cause célèbre over the years has been portrayed by the Albanian media as a "rebel patriot".[55] Nevertheless, he enjoys very limited support in Albania.[56]

Orthodox Autocephalous Church opposed the legalisation of same-sex marriages for LGBT communities in Albania, as did the Muslim and Catholic Church leaders of the country.[57][58]

Demographics

Historical demographics

Although Islam is the dominant religion in Albania, in the southern regions, Orthodox Christianity was traditionally the prevailing religion before the declaration of Albanian independence (1913). However, their number decreased over the following years:[59]

| Year | Orthodox Christians | Muslims |

|---|---|---|

| 1908 | 128,000 | 95,000 |

| 1923 | 114,000 | 109,000 |

| 1927 | 112,000 | 114,000 |

However, some of this decrease was accounted for by the changing of the boundaries of districts by the newly independent Albania.[60] Additionally, the Orthodox Christians of Southern Albania had a greater tendency to migrate than their Muslim neighbors (at first, at least) in the early 20th century. Many of the Orthodox Albanians would ultimately return from the Western countries they emigrated to.[61]

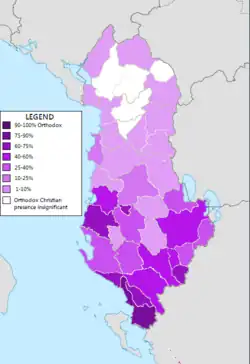

Around the fall of the Ottomon empire, as based on the late Ottoman census of 1908 and the Austrian-run Albanian census of 1918, the regions that retained the highest percentages of Orthodox Albanians, in some cases absolute majorities, were in the South (especially around Saranda, Gjirokastra, Përmeti, Leskoviku, Pogradeci and Korça[60]) and the Myzeqe region of Central Albania (especially around Fier, where they formed a strong majority of the population). There were also large Albanian Orthodox populations in the regions of Elbasan and Berat. Contrary to the stereotype of only Tosks being Orthodox, Orthodox Albanians were also present in the North, where they were spread out at low frequencies in most regions.[62] Orthodox Albanians reached large proportions in some Northern cities: Durrësi (36%), Kavaja (23%) and Elbasani (17%).[63] Orthodox Albanians tended to live in either urban centers or in highland areas, but rarely in rural lowland areas (with the exception of in the region of Myzeqe).

2011 census and reactions

In the 2011 census the declared religious affiliation of the population was: 56.7% Muslims, 13.79% undeclared, 10.03% Catholics, 6.75% Orthodox believers, 5.49% other, 2.5% Atheists, 2.09% Bektashis and 0.14% other Christians.[64] However, the Orthodox Church of Albania officially rejected the specific results, claiming it was "totally incorrect and unacceptable".[65]

Although the question regarding religion was optional, only to be answered by those who chose to, like the question about ethnic origin, it has become the central point of discussion and interest of this census.

The Albanian Orthodox church refused to recognize the results, saying they had drastically underrepresented the number of Orthodox Christians and noted various indications of this and ways it may have occurred.[66] The Orthodox church claimed that from its own calculations, the Orthodox percentage should have been around 24%, rather than 6.75%.

In addition to boycotts of the census, Orthodox numbers may also be underrepresented because the census staff failed to contact a very large number of people in the south which is traditionally an Orthodox stronghold.[67][68][69][70] Furthermore, The Orthodox Church said that according to a questionnaire it gave its followers during two Sunday liturgies in urban centers such as Durrësi, Berati and Korça, only 34% of its followers were actually contacted.[66] There were other serious allegations about the conduct of the census workers that might have impacted on the 2011 census results. There were some reported cases where workers filled out the questionnaire about religion without even asking the participants or that the workers used pencils which were not allowed.[71] In some cases communities declared that census workers never even contacted them.[72] In addition to all these irregularities, the preliminary results released seemed to give widely different results, with 70% of respondents refusing to declare belief in any of the listed faiths,[73] compared with only 2.5% of atheists and 13.8% undeclared in the final results. An Orthodox Albanian politician Dritan Prifti who at the time was a prominent MP for the Myzeqe region referred to fluctuating census numbers regarding the Orthodox community as being due to an "anti-Orthodox agenda" in Albania.[74]

Orthodox Albanians were not the only ones to claim the census underrepresented their numbers: the Bektashi leadership also lambasted the results, which even more drastically reduced their representation down to 2%, and said it would conduct its own census to refute the results, while minority organizations of Greeks (mostly Orthodox) and Roma (mostly Muslim) also claimed they underrepresented, with the Greek organization Omonia arguing that this was linked to the under-representation of the Orthodox population.[72]

According to the Council of Europe ("Third Opinion of the Council of Europe on Albania adopted 23.11.2011,") the population census "cannot be considered to be reliable and accurate, raises issues of compatibility with the principles enshrined in Article 3 of the Framework Convention…The Advisory Committee considers that the results of the census should be viewed with the utmost caution and calls on the authorities not to rely exclusively on the data on nationality collected during the census in determining its policy on the protection of national minorities."[75]

Moreover, the World Council of Churches (WCC) general secretary Rev. Dr Olav Fykse Tveit has expressed concern at the methodology and results of the Albania Census 2011. He has raised questions in regard to the reliability of the process which, he said, has implications for the rights of religious minorities and religious freedoms guaranteed in the country's constitution. Tveit expressed this concern in letters issued at the beginning of May to the WCC president Archbishop Anastasios, to Prof. Dr Heiner Bielefeldt, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, and to the Albanian government.[76]

Demographics in the early 2020s

Figures in 2022 note that 18.42% of the population are Orthodox Christians.[77]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Saint Nicholas in Mesopotam, Albania

Saint Nicholas in Mesopotam, Albania_korr2.jpg.webp) Ardenica Monastery in Ardenica, Albania.

Ardenica Monastery in Ardenica, Albania. Old Orthodox Church in Berat

Old Orthodox Church in Berat

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Paul, St" Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ Raymond Zickel; Walter R. Iwaskiw, eds. (1994). ""The Ancient Illyrians," Albania: A Country Study". Retrieved 9 April 2008. index of the work

- ↑ "What Are the Origins of Today's Albanians?". Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramet 1998, p. 202.

- 1 2 Stavrianos 2000, pp. 497–498. "Religious differences also existed before the coming of the Turks. Originally, all Albanians had belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church, to which they had been attached at the time of the schism between the church of Rome and that of Constantinople. Then the Ghegs in the North adopted Catholicism, apparently in order to better resist the pressure of Orthodox Serbs. Thus the Albanians were divided between the Catholic and Orthodox churches before the time of the Turkish invasion."

- ↑ Kopanski 1997, pp. 193–194.

- 1 2 3 4 Lederer 1994, pp. 333–334.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ramet 1998, p. 203. "The Ottoman conquest between the end of the fourteenth century and the mid-fifteenth century introduced a third religion – Islam - but the Turks did not at first use force in its expansion, and it was only in the 1600s that large-scale conversion to Islam began – chiefly, at first, among Albanian Catholics."; p.204. "The Orthodox community enjoyed broad toleration at the hands of the Sublime Porte until the late eighteenth century."; p. 204. "In the late eighteenth century Russian agents began stirring up the Orthodox subjects of the Ottoman empire against the Sublime Porte. In the Russo-Turkish wars of 1768-74 and 1787-91 Orthodox Albanians rose against the Turks. In the course of the second revolt the "New Academy" in Voskopoje was destroyed (1789), and at the end of the second Russo-Turkish war more than a thousand Orthodox fled to Russia on Russian warships. As a result of these revolts, the Porte now applied force to Islamicize the Albanian Orthodox population, adding economic incentives to provide positive stimulus. In 1798 Ali Pasha of Janina led Ottoman forces against Christian believers assembled in their churches to celebrate Easter in the villages of Shen Vasil and Nivica e Bubarit. The bloodbath unleashed against these believers frightened Albanian Christians in other districts and inspired a new wave of mass conversions to Islam."

- ↑ Ergo 2010, p. 26.

- 1 2 Ergo 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Giakoumis 2010, pp. 79–81.

- 1 2 3 Giakoumis 2010, p. 84.

- ↑ Ergo 2010, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Skendi 1967a, pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Winnifrith 2002, p. 107."But the difficult archbishops of Ohrid must have produced some difference in their flocks. Less contentious faiths were available. It so happens that converting to Islam in central Albania was eased by the strength there of the Bektashi cult, a mystical faith, designed to appeal to all, demanding little in the way of strict rules of observance."

- 1 2 Pistrick 2013, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 Skendi 1956, pp. 316, 318–320.

- 1 2 Skendi 1956, pp. 321–323.

- 1 2 Vickers 2011, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Koti 2010, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Kallivretakis 2003, p. 233.

- 1 2 Hammond 1967, p. 30.

- ↑ Anscombe 2006, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 Hammond 1976, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Koukoudis 2003, pp. 321–322. "Particularly interesting is the case of Vithkuq, south of Moschopolis, which seems to have shared closely in the town's evolution, though it is far from clear whether it was inhabited by Vlachs [Aromanians] in the glory days before 1769. It may well have had Vlach inhabitants before 1769, though the Arvanites were certainly far more numerous, if not the largest population group. This is further supported by the linguistic identity of the refugees who fled Vithkuq and accompanied the waves of departing Vlachs. Today it is inhabited by Arvanites and Vlachs, though the forebears of the modern Vlach residents arrived after the village had been abandoned by its previous inhabitants and are mainly of Arvanitovlach descent. They are former pastoral nomads who settled permanently in Vithkuq."; p. 339. "As the same time as, or possibly shortly before or after, these events in Moschopolis, unruly Arnauts also attacked the smaller Vlach and Arvanitic communities round about. The Vlach inhabitants of Llengë, Niçë, Grabovë, Shipckë, and the Vlach villages on Grammos, such as Nikolicë, Linotopi, and Grammousta, and the inhabitants of Vithkuq and even the last Albanian speaking Christian villages on Opar found themselves at the mercy of the predatory Arnauts, whom no-one could withstand. For them too, the only solution was to flee... During this period, Vlach and Arvanite families from the surrounding ruined market towns and villages settled alongside the few Moscopolitans who had returned. Refugee families came from Dushar and other villages in Opar, from Vithkuq, Grabovë, Nikolicë, Niçë, and Llengë and from Kolonjë."

- 1 2 3 Jorgaqi 2005, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Winnifrith 2002, p. 109. "Of these Vithkuq... All these villages have a Vlach [Aromanian] element in their population, and it is Vlach tradition that they were large and important... This culture was of course Greek culture...

- 1 2 Giakoumis 2010, pp. 89–91.

- 1 2 Elsie 2001, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Elsie 2000, p. 48.

- ↑ Mackridge 2009, pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 3 Giakoumis 2010, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Norris 1993, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Ramet 1998, p. 210. "In general, a pattern emerged. When the Ottoman empire was attacked by Catholic powers, local Catholics were pressured to convert, and when the attack on the Ottoman empire came from Orthodox Russia, the pressure was on local Orthodox to change faith."

- ↑ Skendi 1967b, pp. 235–242.

- ↑ Pistrick 2013, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Duijzings 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ Austin 2012, p. 4.

- 1 2 Biernat 2014, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ "Statuti Kishës Orthodhokse Autoqefale Kombë tare të Shqipërisë" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ Russell King, Nicola Mai (2013). Out Of Albania: From Crisis Migration to Social Inclusion in Italy. Berghahn Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780857453907.

- ↑ Albanien: Geographie - historische Anthropologie - Geschichte - Kultur ... By Peter Jordan, Karl Kaser, Walter Lukan, Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, Holm Sundhaussen page 302

- 1 2 Forest, Jim The Resurrection of the Church in Albania, World Council of Churches Publication, August 2002, ISBN 2-8254-1359-3

- ↑ Barkas, Panagiotis (17 August 2013). "Violent Clashes against Clergy and Faithful in Permet". skai.gr. Athens News Agency. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2014: Albania" (PDF). state.gov/. United States, Department of State. p. 4. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- 1 2 Diamadis, Panayiotis (Spring 2014). "Clash of Eagles with Two Heads: Epirus in the 21st Century" (PDF). American Hellenic Institute Foundation Policy Journal: 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

Clergy and faithful were violently ejected from an Orthodox church in Premeti during the celebrations for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on 16 August 2013, by private security and municipal authorities. Religious items such as icons and utensils were also confiscated.

- ↑ Watch, Human Rights; [Researched, Helsinki.; Abrahams], written by Fred (1996). Human rights in post-communist Albania. New York [u.a.]: Human Rights Watch. p. 157. ISBN 9781564321602.

A further point of contention between the Albanian Orthodox Church and the Albanian government is the return of church property.... In addition many holy icons and vessels of the Orthodox Church are being held in national museums, allegedly because of the Albanian government is concerned with protecting these valuable objects.... other church property that have been allegedly not been fully returned by the state include, the Cathedral of the Assumption in Permet

- ↑ "Conflict in Permet about the Church, police takes control of the House of Culture". Independent Balkan News Agency. August 28, 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Todorova Marii︠a︡ Nikolaeva. Balkan identities: nation and memory. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2004 ISBN 978-1-85065-715-6, p. 107

- ↑ Sina, Beqir (28 January 2014). "Protestë kundër kryepeshkopit Anastasios në hyrje të Fordham University [Protest against Archbishop Anastasios at the interance of Fordham University] Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine". Illyria. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Ndrenika, Denion (03 March 2014). "Fatos Klosi: Kisha Ortodokse më keq se islamikët, “pendesa” për vrasjen e Tivarit [Fatos Klosi: Orthodox Church worse than Islamists, "remorse" for the killing of Tivari] Archived 2016-08-10 at the Wayback Machine". Illyria. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Tema Online (12 December 2012). "Fatos Klosi: Kisha greke si strukture diktatoriale, s'duron opinione ndryshe [Fatos Klosi: Greek Church as dictatorial structure, it does not bear different opinions]". Gazeta Tema. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Respublica (09 April, 2014). "KOASH pas deklaratave të Fatos Klosit: Qëndrime arbitrare dhe çorientuese. Kisha e Shqipërisë është Autoqefale. Ringritjen e saj e inicioi Patriarkana [KOASH after statements by Fatos Klosi: Arbitrary and misleading attitudes. The Church of Albania is autocephalous. Its rebuilding was initiated by the Patriarchate]". Respublica. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ KohaNet (9 April 2014). "Ortodokse kundër Fatos Klosit: Hedh helm s'varemi nga greku [Orthodox Church against Fatos Klosi: He throws poison, though we are not dependent on the Greeks]". KohaNet. Retrieved 14 June 2016. Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mejdini, Fatjona (04 April 2016). "New Diocese Reopens Old Wounds in Albanian Church". Balkaninsight. Retrieved 14 June 2016. "The creation of a new diocese in the Albanian Orthodox Church has caused an angry row between the Church authorities and a rebel priest - who has often accused it in the past of acting as the agent of Greece.The creation of the Elbasan diocese on April 17 was vehemently denounced on Tuesday by local cleric Fr Nikolla Marku who for a long time has opposed the ethnically Greek Church head, Archbishop Janullatos. Fr Marku, who runs the church of' St Mary in Elbasan, told the newly appointed Bishop, or Metropolitan, of Elbasan, Andoni, to resign. Headed by Archbishop Janullatos, the Church has had repeated disputes with Fr Marku, who the media often style a rebel patriot... Headed by Archbishop Janullatos, the Church has had repeated disputes with Fr Marku, who the media often style a rebel patriot.Albanian Church spokesperson Thoma Dhima told BIRN that Fr Marku has no official relationship with the Church, which considers him only a "private citizen"... Fr Marku separated himself from the local Orthodox Church since the 1990s, considering it a bastion of Greek chauvinism and a promoter of divisions in the Orthodox community."

- ↑ Leustean, Lucian (2014). Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. p. 234. ISBN 9781317818663.

- ↑ "Albania 'to approve gay marriage'". BBC. 30 July 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ Çako, Miron (17 May 2016). "Përse Kisha Orthodhokse është kundër martesave “homoseksuale”? [Why is the Orthodox Church against "homosexual" marriage?]". Tirana Observer. Retrieved 14 June 2016. Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Nußberger Angelika, Wolfgang Stoppel (2001), Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien) (PDF) (in German), Universität Köln, p. 75, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03, retrieved 2017-04-30,

p. 14

- 1 2 Psomas, Lambros A. Synthesis of the Population of Southern Albania (2008).

- ↑ De Rapper, Gilles. Religion in post-communist Albania: Muslims, Christians and the idea of 'culture' in Devoll, southern Albania (2008).

- ↑ Grüber, Siegfried. Regional variation in marriage patterns in Albania at the beginning of the 20th century. Available here: http://www-gewi.uni-graz.at/seiner/marriage_patterns.html Archived 2019-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Demographic maps by Franz Seiner, based on data from the Austrian-run 1918 Albanian census. Available here: http://www-gewi.uni-graz.at/seiner/density.html Archived 2019-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Albanian census 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-14. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Official Declaration: The results of the 2011 Census regarding the Orthodox Christians in Albania are totally incorrect and unacceptable". orthodoxalbania.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- 1 2 "Official Declaration: The results of the 2011 Census regarding the Orthodox Christians in Albania are totally incorrect and unacceptable". orthodoxalbania.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ Kisha Ortodokse: S’njohim censusin - Top Channel

- ↑ "AK- Nishanit: Hiqi 'Urdhrin e Skënderbeut' Janullatosit, dekoro themeluesit e Kishës Autoqefale Shqiptare (LETRA) | Gazeta Tema". Archived from the original on 2015-05-16. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Prifti: Në Shqipëri ka një axhendë anti-ortodokse | Gazeta Tema". Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "INTERVISTA/ Vangjel Dule: Autorët e censusit, manipulatorë të realitetit. Rezoluta çame? historia nuk ribëhet | Gazeta Tema". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Censusi, shumë prej pyetjeve plotësoheshin nga vetë anketuesit | Gazeta Tema". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- 1 2 "Final census findings lead to concerns over accuracy". Tirana Times. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "Censusi permbys fete, 70 per qind refuzojne ose nuk e deklarojne besimin". Shqiperia.com.

- ↑ Tema Online (12 December 2012). "Prifti: Në Shqipëri ka një axhendë anti-ortodokse [Prifti: In Albania, there is an Anti-Orthodox agenda] Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine". Gazeta Tema. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "Third Opinion on Albania, adopted on 23 November 2011. Published Strasbourg 4 June 2012. Available here: http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/minorities/3_fcnmdocs/PDF_3rd_OP_Albania_en.pdf

- ↑ WCC general secretary

- ↑ The Archive of Religion Data Archives website, Retrieved 2023-07-18

Sources

- Anscombe, Frederick (2006). "Albanians and "mountain bandits"". In Anscombe, Frederick (ed.). The Ottoman Balkans, 1750–1830. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. pp. 87–113. ISBN 9781558763838. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25.

- Austin, Robert Clegg (2012). Founding a Balkan State: Albania's Experiment with Democracy, 1920-1925. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442644359.

- Biernat, Agata (2014). "Albania and Albanian émigrés in the United States before World War II". In Mazurkiewicz, Anna (ed.). East Central Europe in Exile Volume 1: Transatlantic Migrations. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 9–22. ISBN 9781443868914.

- Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9780230119086.

- Babuna, Aydin (2004). "The Bosnian Muslims and Albanians: Islam and Nationalism". Nationalities Papers. 32 (2): 287–321. doi:10.1080/0090599042000230250. S2CID 220352072.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2005). "Le meurtre du prêtre: Acte fondateur de la mobilisation nationaliste albanaise à l'aube de la révolution Jeune Turque [The murder of the priest: Founding act of the Albanian nationalist mobilisation on the eve of the Young Turks revolution]". Balkanologie. IX (1–2).

- Clayer, Nathalie (2005b). "Convergences and Divergences in Nationalism through the Albanian example". In Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (eds.). Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: Convergence vs. Divergence. Brussels: Peter Lang. pp. 213–226. ISBN 9789052012971.

- De Rapper, Gilles (2009). "Pelasgic Encounters in the Greek-Albanian Borderland. Border Dynamics and Reversion to Ancient Past in Southern Albania" (PDF). Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. 18 (1): 50–68. doi:10.3167/ajec.2009.180104. S2CID 18958117.

- Duijzings, Gerlachlus (2000). Religion and the politics of identity in Kosovo. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654315.

- Elsie, Robert (2000). "The Christian Saints of Albania". Balkanistica. 13 (36): 35–57.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology, and folk culture. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850655701.

- Ergo, Dritan (2010). "Islam in the Albanian lands (XVth-XVIIth Century)". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens (ed.). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa [Religion and culture in Albanian-speaking southeastern Europe]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 13–52. ISBN 9783631602959.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2010). "The Orthodox Church in Albania Under the Ottoman Rule 15th-19th Century". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens (ed.). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa [Religion and culture in Albanian-speaking southeastern Europe]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 69–110. ISBN 9783631602959.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198142539.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1976). Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas. Park Ridge: Noyes Press. ISBN 9780815550471.

- Jorgaqi, Nasho (2005). Jeta e Fan S. Nolit: Vëllimi 1. 1882–1924 [The life of Fan S. Noli: Volume 1. 1882–1924]. Tiranë: Ombra GVG. ISBN 9789994384303.

- Kallivretakis, Leonidas (2003). "Νέα Πικέρνη Δήμου Βουπρασίων: το χρονικό ενός οικισμού της Πελοποννήσου τον 19ο αιώνα (και η περιπέτεια ενός πληθυσμού) [Nea Pikerni of Demos Vouprassion: The chronicle of a 19th century Peloponnesian settlement (and the adventures of a population)]" (PDF). In Panagiotopoulos, Vasilis; Kallivretakis, Leonidas; Dimitropoulos, Dimitris; Kokolakis, Mihalis; Olibitou, Eudokia (eds.). Πληθυσμοί και οικισμοί του ελληνικού χώρου: ιστορικά μελετήματα [Populations and settlements of the Greek villages: historical essays]. Athens: Institute for Neohellenic Research. pp. 221–242. ISSN 1105-0845.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Kokolakis, Mihalis (2003). Το ύστερο Γιαννιώτικο Πασαλίκι: χώρος, διοίκηση και πληθυσμός στην τουρκοκρατούμενη Ηπειρο (1820–1913) [The late Pashalik of Ioannina: Space, administration and population in Ottoman ruled Epirus (1820–1913)]. Athens: EIE-ΚΝΕ. ISBN 978-960-7916-11-2.

- Kopanski, Atuallah Bogdan (1997). "Islamization of Albanians in the Middle Ages: The primary sources and the predicament of the modern historiography". Islamic Studies. 36 (2/3): 191–208. JSTOR 23076194.

- Koti, Dhori (2010). Monografi për Vithkuqin dhe Naum Veqilharxhin [A monograph of Vithkuq and Naum Veqilharxhi]. Pogradec: DIJA Poradeci. ISBN 978-99956-826-8-2.

- Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Thessaloniki: Zitros Publications. ISBN 9789607760869.

- Lederer, Gyorgy (1994). "Islam in Albania". Central Asian Survey. 13 (3): 331–359. doi:10.1080/02634939408400866.

- Mackridge, Peter (2009). Language and national identity in Greece, 1766–1976. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199599059.

- Malcolm, Noel (2002). "Myths of Albanian national identity: Some key elements". In Schwanders-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd J. (eds.). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 70–87. ISBN 9780253341891.

- Nitsiakos, Vassilis (2010). On the border: Transborder mobility, ethnic groups and boundaries along the Albanian-Greek frontier. Berlin: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643107930.

- Norris, Harry Thirlwall (1993). Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872499775.

- Pipa, Arshi (1989). The politics of language in socialist Albania. Boulder: East European Monographs. ISBN 9780880331685.

- Pistrick, Eckehard (2013). "Interreligious Cultural Practice as Lived Reality: The Case of Muslim and Orthodox Shepherds in Middle Albania". Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. 22 (2): 72–90. doi:10.3167/ajec.2013.220205.

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9781850652380.

- Puto, Artan; Maurizio, Isabella (2015). "From Southern Italy to Istanbul: Trajectories of Albanian Nationalism in the Writings of Girolamo de Rada and Shemseddin Sami Frashëri, ca. 1848–1903". In Maurizio, Isabella; Zanou, Konstantina (eds.). Mediterranean Diasporas: Politics and Ideas in the Long 19th Century. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472576668.

- Skendi, Stavro (1956). "Religion in Albania during the Ottoman rule". Südost Forschungen. 15: 311–327.

- Ramet, Sabrina (1998). Nihil obstat: religion, politics, and social change in East-Central Europe and Russia. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822320708.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967a). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400847761.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967b). "Crypto-Christianity in the Balkan Area under the Ottomans". Slavic Review. 26 (2): 227–246. doi:10.2307/2492452. JSTOR 2492452. S2CID 163987636.

- Skoulidas, Elias (2013). "The Albanian Greek-Orthodox Intellectuals: Aspects of their Discourse between Albanian and Greek National Narratives (late 19th - early 20th centuries)". Hronos. 7. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000). The Balkans Since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 9781850655510.

- Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9780857736550.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 9780715632017.