Eastern Ukraine or east Ukraine (Ukrainian: Східна Україна, romanized: Skhidna Ukrayina; Russian: Восточная Украина, romanized: Vostochnaya Ukraina) is primarily the territory of Ukraine east of the Dnipro (or Dnieper) river, particularly Kharkiv, Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts (provinces). Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts are often also regarded as "eastern Ukraine". In regard to traditional territories, the area encompasses portions of the southern Sloboda Ukraine, Donbas, the eastern Azov Littoral (Pryazovia).

Almost a third of the country's population lives in the region, which includes several cities with population of around a million. Within Ukraine, the region is the most highly urbanized, particularly portions of central Kharkiv Oblast, south-western Luhansk Oblast, central, northern and eastern areas of Donetsk Oblast.

Geography

The region stretches from southern areas of the Central Russian Upland to the northern shores of the Sea of Azov, from the eastern border with Russia to Black Sea and Dnieper Lowlands (including the left bank of the Dnipro) to the west. Other than the Dnipro, the major river of eastern Ukraine is the Siverskyi Donets. The main economic region of that part of the country is the Donbas, whose name is a contraction of "Donets Basin", named after the Siverskyi Donets. The region became the scene of an armed conflict between Ukraine and Russian proxy forces.

Cities and population

The territory is heavily urbanized and commonly associated with the Donbas. The three largest metropolitan cities form an industrial triangle within the region. Among the major cities with population of over 200,000 people are Kharkiv, Dnipro, Donetsk-Makiivka, Zaporizhzhia, Mariupol, Luhansk, Horlivka and Kamianske. Donetsk and Makiivka create urban sprawl, with very close proximity to other important cities such as Horlivka and Yenakieve.

| Oblast (province) | Ukrainian name | Area in km2 | Population at 2001 Census | Population at 2012 estimate | Notes [1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donetsk | Донецька область | 26,517 | 4,825,563 | 4,403,178 | |

| Kharkiv | Харківська область | 31,418 | 2,914,212 | 2,742,180 | |

| Luhansk | Луганська область | 26,683 | 2,546,178 | 2,272,676 | |

| Total for 3 oblasts | 84,618 | 10,285,953 | 9,418,034 | ||

| Zaporizhzhia | Запорізька область | 27,183 | 1,929,171 | 1,791,668 | |

| Dnipropetrovsk | Дніпропетровська область | 31,923 | 3,561,224 | 3,320,299 | |

| Total for 5 oblasts | 143,724 | 15,776,348 | 14,530,001 | ||

Demographics

Ethnicity and language

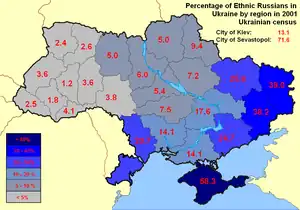

According to the 2001 census, the majority of eastern Ukraine's population are ethnic Ukrainians, while ethnic Russians form a significant minority. The most common language in urban areas of the Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts is Russian, having long dominated in government and the media. When Ukraine became independent, there were no Ukrainian-language schools in Donetsk.[2]

Noticeable cultural differences in the region (compared with the rest of Ukraine except Southern Ukraine) are more "positive views" on the Russian language[3][4] and on the Soviet era[5][6] and more "negative views" on Ukrainian nationalism.[5]

Effective in August 2012, a law on regional languages entitled any local language spoken by at least a 10% of the population to be declared official within that area.[7] Within weeks, Russian was declared as a regional language in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities.[8] From that point Russian could be used in those cities'/oblasts' administrative office work and documents.[9] On 23 February 2014, the law on regional languages was abolished, making Ukrainian the sole state language at all levels even in eastern Ukraine,[10] but this vote was vetoed by acting President Oleksandr Turchynov on 2 March.[11][12] A February 2015 survey found that eastern oblasts (61%) preferred "second official regional language" over (31%) "state language" status for Russian.[13] The 2012 law on regional languages was repealed by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine on 28 February 2018 when it ruled the law unconstitutional.[14]

Religion

Religion in eastern Ukraine (excluding Donbas), 2016[15]

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine held by the Razumkov Center, 73.5% of the population in eastern Ukraine were Christians (63.2% Eastern Orthodox, 8.1% simply Christians, 1.0% Protestants, and 0.3% Latin Catholics), 0.5% were Muslims, 0.3% were Jewish, and 0.3% were Hindus. Not religious and other believers not identifying with any of the listed major religious institutions constituted about 24.7% of the population.[15] It also showed that approximately 55.6% of the population of eastern Ukraine (which in Razumkov's mapping excluded Donbas and consisted of the regions immediately to the west of it) declared to be believers, while 13.4% declared to be undecided or non-believers, and 3.5% declared to be atheist.[15]

Politics

A large majority of voters in eastern Ukraine (83% or more in each oblast) approved Ukraine's declaration of independence in the 1991 referendum, though the majority was not as big as in the west.[16][17]

A 2007 survey by the Razumkov Centre asked "Would you like to have your region separated from Ukraine and joined another state?" In eastern Ukraine, 77.9% of respondents disagreed, 10.4% agreed, and the rest were undecided.[18]

In elections, voters of the eastern (and southern) oblasts of Ukraine voted for parties (Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), Party of Regions) and presidential candidates (Viktor Yanukovych) with a pro-Russian and status quo platform.[19][20][21] The electorate of CPU and Party of Regions was very loyal to them.[21] But following the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution the Party of Regions collapsed[22] and the CPU was banned and declared illegal.[23]

In a poll conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014, 25.8% of those polled in eastern Ukraine believed that "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5%.[24]

In 2014, the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine took place in parts of eastern Ukraine. Some protesters allegedly came from Russia to support the unrest.[25][26] The war in Donbas resulted in thousands of deaths and over a million people leaving their homes.[27] Today, parts of the region are controlled by the self-proclaimed and internationally not-recognized Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic. On 24 February 2022, the region became the scene of the eastern Ukraine offensive.

A November 2015 poll carried out by Rating Group Ukraine in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, except in the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People's Republic (LPR)-controlled areas, found that 75% of residents wanted the entire Donbas region to stay in Ukraine, 7% said that it should join Russia, 1% wanted it to become an independent country, and 3% said that the DPR and the LPR-controlled territories should leave and the rest of Donbas remain in Ukraine.[28] When asked if Russian-speaking citizens are under pressure or threat, 82% said 'no' and 11% said 'yes'.[28] 2% "definitely" and 7% "somewhat" supported Russia sending troops to "protect" Russian-speakers in Ukraine, while 71% did not.[28] 50% wanted Ukraine to remain a unitary country, 14% wanted it to be a federal country, 13% said it should remain unitary but without Crimea, and 7% wanted it to be divided into several countries.[28] If they had to choose between the Eurasian Customs Union and the European Union, 24% in eastern Ukraine (including Kharkiv Oblast) preferred the ECU and 20% preferred the EU (in Donbas: 33% for the ECU, 21% for the EU). On joining NATO, 15% were for, 15% were against, and most said that they would not vote or it was difficult to answer (in Donbas: 16% for, 47% against).[28] Eastern Ukrainians were less likely to vote in parliamentary elections.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ All statistics sourced from: State Statistics Committee of "Ukraine".

- ↑ Eternal Russia:Yeltsin, Gorbachev, and the Mirage of Democracy by Jonathan Steele, Harvard University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0-674-26837-1 (page 218)

- ↑ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ↑ "Poll: Over half of Ukrainians against granting official status to Russian language – Dec. 27, 2012". 27 December 2012.

- 1 2 Who’s Afraid of Ukrainian History? by Timothy D. Snyder, The New York Review of Books (21 September 2010)

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Ставлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013)

- ↑ Yanukovych signs language bill into law. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ↑ Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ↑ Romanian becomes regional language in Bila Tserkva in Zakarpattia region, Kyiv Post (24 September 2012)

- ↑ Ukraine: Speaker Oleksandr Turchynov named interim president, BBC News (23 February 2014)

- ↑ Traynor, Ian (24 February 2014). "Western nations scramble to contain fallout from Ukraine crisis". The Guardian.

- ↑ Kramer, Andrew (2 March 2014). "Ukraine Turns to Its Oligarchs for Political Help". New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ Halya Coynash (13 April 2015). "Bad News for Moscow on the Language Front". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Constitutional Court declares unconstitutional language law of Kivalov-Kolesnichenko, Ukrinform (28 February 2018)

- 1 2 3 РЕЛІГІЯ, ЦЕРКВА, СУСПІЛЬСТВО І ДЕРЖАВА: ДВА РОКИ ПІСЛЯ МАЙДАНУ (Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan) Archived 2017-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, 2016 report by Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches. pp. 27–29.

- ↑ Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 128)

- ↑ Ivan Katchanovski. (2009). Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montreal, June 1–3, 2010

- ↑ "Would you like to have your region separated from Ukraine and joined another state (regional distribution)". Razumkov Centre. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 396)

- ↑ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)

- 1 2 Eight Reasons Why Ukraine’s Party of Regions Will Win the 2012 Elections by Taras Kuzio, The Jamestown Foundation (17 October 2012)

UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again Archived 2013-05-15 at the Wayback Machine by Taras Kuzio, Oxford Analytica (5 October 2007) - ↑ (in Ukrainian) "Revival" "our land": Who picks up the legacy of "regionals", BBC Ukrainian (16 September 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Party of Regions: Snake return, The Ukrainian Week (2 October 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Activists noticed that most ex-Regions are on lists of Poroshenko, Ukrayinska Pravda (22 October 2015) - ↑ Symonenko: Communists will go to elections as part of "Nova Derzhava" party (Симоненко: комуністи підуть на вибори у складі партії «Нова держава»). Radio Liberty. 25 September 2015

- ↑ "How relations between Ukraine and Russia should look like? Public opinion polls' results". Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Roth, Andrew (4 March 2014). "From Russia, 'Tourists' Stir the Protests". The New York Times.

"Russian site recruits 'volunteers' for Ukraine". BBC News. 4 March 2014. - ↑ "Protesters Storm Kharkiv Theater Thinking It Was City Hall". The Moscow Times. 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine Situation report No.33 as of 27 March 2015" (PDF). OCHA. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "IRI's Center for Insights Poll: Pessimism High after Two Years of Violent Conflict with Russia; People in the Ukrainian-Controlled Territories of Donbas Want to Remain Part of Ukraine". International Republican Institute. 12 January 2016.

Further reading

- Serhy Yekelchyk Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3, page 187