| Argyll's Regiment of Foot Lord Lorne's Regiment (from April 1694) | |

|---|---|

| Active | April 1689 - February 1697 |

| Disbanded | February 1697 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Line infantry |

| Garrison/HQ | Perth Fort William Brentford Diksmuide Damme |

| Engagements | Jacobite Rising 1689-92 Massacre of Glencoe Nine Years' War Storming of Dottignies Siege of Dixsmuide |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | The Duke of Argyll to April 1694 Lord Lorne to February 1697 |

| Lt-Colonel | Duncan Campbell Robert Jackson Patrick Hume Robert Duncanson |

Argyll's Regiment of Foot was a Scottish infantry regiment formed in April 1689 to suppress Jacobite opposition in the Highlands. In February 1692 it took part in the Glencoe Massacre, moved to Brentford near London in May then to Flanders in early 1693 where it fought in the Nine Years War. It became Lord Lorne's Regiment in April 1694 and was disbanded on February 1697.

Formation

On 19 April 1689, the Earl of Argyll was commissioned by the Parliament of Scotland to raise a regiment of 600 men, later expanded to 800; it was the first regular Highland regiment rather than militia.[lower-alpha 1][1] Experience of the New Model Army, which ruled England and Scotland for much of the English Commonwealth, meant politicians in the late 17th century saw standing armies as a danger to the liberties of the individual and a threat to society itself.[2] To prevent this, regiments were treated as the personal property of their Colonel, changed names when transferred and were disbanded as soon as possible.[3]

Commissions were assets that could be bought, sold or used as an investment; one person could simultaneously hold multiple commissions and there were no age restrictions. They did not require actual service, and at senior levels in particular, ownership and command were separate functions. While many colonels or lieutenant colonels played active military roles, others remained civilians who delegated their duties to a subordinate.[4]

An individual could join a regiment in Scotland, be appointed to another in Flanders, then transfer to one in Jamaica without ever leaving Edinburgh or participating in military duties. Many fail to appreciate this; Robert Holden's 1905 article devotes much space to defending the Earl of Argyll, on the assumption that as Colonel he participated in Glencoe massacre.[5]

In most regiments, operational command was exercised by the Lieutenant-Colonel, the first being Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck, whose family were hereditary Lieutenant-Colonels to the Earls of Argyll. He was succeeded by Robert Jackson in June 1691, then Patrick Hume, who was severely wounded at the Siege of Namur in July 1695. In reality, Major Robert Duncanson appears to have largely performed this function from July 1690 to disbandment in February 1697.[6]

Highland regiments were formed by first appointing Captains, usually landowners or minor gentry, each responsible for recruiting sixty men from their own estates. Muster rolls of the 2nd Company for October 1691.[7] show the vast majority came from Argyllshire, including Cowal and Kintyre, areas settled by Lowlander migrants and badly affected by the suppression following the 1685 rising.[8] There are relatively few named Campbell but many are from Campbell septs, spelt in a variety of ways.[9]

Officers like Robert Campbell of Glenlyon officially received 8 shillings per day but there were many opportunities to substantially increase this eg deductions for equipment, food etc.[10] Highland regiments could be especially lucrative as the clan system made some military service obligatory, allowing a larger margin between what the government paid and soldiers received. One purpose of muster rolls was to curb the practice of claiming pay for non-existent soldiers, and official numbers should be treated with care.[11]

Scotland; 1689-1692

Still partially trained and understrength,[lower-alpha 2] in July 1689 the Argylls were used to garrison Perth after the Jacobite victory at Killiecrankie. A year later they moved to the new military base at Fort William as part of the force responsible for pacifying the Highlands. This was commanded by Colonel John Hill, the military governor and included Hill's own regiment under Lt-Colonel Hamilton which is sometimes confused with the Argylls. The next 18 months were spent retaking or destroying Jacobite strongpoints including Castle Stalker, Duart Castle and Cairnburgh Castle.[12]

In the winter of 1691/92, the Argylls were besieging Invergarry Castle, primary seat of MacDonald of Glengarry. A witness later testified that at the end of January 1692 two companies of the Argylls under Glenlyon came to Glencoe from the north Glengarry's house being reduced.[13] They were carrying orders to collect tax or 'cess' payments; the Highlands was a largely non-cash society and 'free quarter' commonly used as an alternative.[14] Although initially suspicious, the MacDonalds accepted their presence while individual Argyll soldiers later testified they were unaware of any other motive until the morning of 13 February.[15]

As instructed by Lord Stair Secretary of State for Scotland, Hill ordered Hamilton to block the northern exits from Glencoe at Kinlochleven with 400 men of Hills Regiment. At the same time, 400 men from the Argylls under Major Duncanson would join Glenlyon's detachment and sweep northwards up the glen, killing anyone they found, removing property and burning houses.[16]

On the evening of the 12th, Duncanson sent his own orders to Glenlyon carried by Captain Drummond, commander of the Argyll's Grenadier company and thus senior Captain.[lower-alpha 4] Glenlyon was to commence the killings at 5:00 am the next day, with Duncanson joining him as close to that time as possible but whether by accident or design, both he and Hamilton arrived only after the killings were over. Details given to the 1695 Commission report the deaths of around 30 men, including nine who were first tied up and then shot.[17] Recent estimates put total deaths resulting from the Massacre as 'around 30', while claims others died of exposure have not been substantiated.[18]

The Parliamentary Commission of 1695 focused on whether orders had been exceeded, not their legality. They concluded Stair and Hamilton had a case to answer but left the decision to William. No charges were ever brought against those involved.[19]

England and Flanders; 1692-1697

In May 1692, fears of a Jacobite invasion meant the Argylls and other Scottish units were transferred onto the English military establishment and based at Brentford in England. The invasion threat was ended by the Anglo-Dutch naval victories of Barfleur and La Hogue and the Argylls sent to Flanders in early 1693. On 9 July, the regiment took part in an assault on the French fortifications at Dottignies in current day Belgium and suffered heavy casualties, particularly among the Grenadier company led by Captain Drummond.[20]

In April 1694, Argyll transferred his commission as Colonel to his eldest son, Lord Lorne and it became known as Lord Lorne's Regiment.[21] Colonel Hume was severely wounded at Namur in 1695, leaving Duncanson in command when the regiment was part of the garrison of Diksmuide, an important strategic position.[22] This was besieged by the French; the Allied commander Ellenberg capitulated after only two days but Duncanson refused to sign the terms of surrender. Ellenberg was later executed while Duncanson was promoted to Lt-Colonel in August as a reward.[10]

Garrisons who surrendered were normally allowed free passage rather than being held prisoner and Lorne's was released and went into winter quarters at Damme. By 1696 the war in the Netherlands was winding down and the unit engaged in garrison duties around Nieuport and Bruges. Lorne's is listed in the records of the House of Commons as disbanded or 'broke' in February 1697, shortly before the Treaty of Ryswick in September 1697.[23]

Footnotes

- ↑ This is often debated but tracing the origins of modern regiments is extremely complex; many regimental histories were written in the late 19th or early 20th century when establishing regimental precedence or seniority was almost an obsession.

- ↑ At this stage, only five of the eight authorised companies had been recruited.

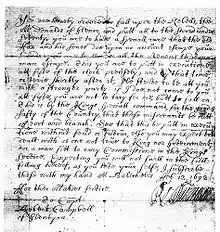

- ↑ You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebells, the McDonalds of Glenco, and put all to the sword under seventy. you are to have a speciall care that the old Fox and his sones doe upon no account escape your hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man escape. This you are to putt in execution att fyve of the clock precisely; and by that time, or very shortly after it, I’ll strive to be att you with a stronger party: if I doe not come to you att fyve, you are not to tarry for me, but to fall on. This is by the Kings speciall command, for the good & safety of the Country, that these miscreants be cutt off root and branch. See that this be putt in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be dealt with as one not true to King nor Government, nor a man fitt to carry Commissione in the Kings service. Expecting you will not faill in the full-filling hereof, as you love your selfe, I subscribe these with my hand att Balicholis Feb: 12, 1692.

- ↑ Drummond also featured in the Darien Scheme.

References

- ↑ Holden 1905, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Childs 1987, p. 184.

- ↑ Chandler & Beckett 1996, p. 52.

- ↑ Guy 1985, p. 49.

- ↑ Holden 1905, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Dalton 1896, pp. 414–415.

- ↑ Prebble 1973, p. 312.

- ↑ Argyll Transcripts 1891, pp. 12–24.

- ↑ Clan Campbell Society North America. "Official List of Septs of Clan Campbell". Clan Campbell Society. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- 1 2 Walton 1894, p. 389.

- ↑ Guy 1985, p. 33.

- ↑ Holden 1905, pp. 35–40.

- ↑ Cobbett 1814, p. 904.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 141.

- ↑ Scott & Somers 1832, p. 537.

- ↑ Scott & Somers 1832, p. 538.

- ↑ Cobbett 1814, p. 902.

- ↑ Campsie, Alison (12 February 2018). "The Scotsman". Archaeologists trace lost settlements of Glencoe destroyed after 1692 massacre. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Scott & Somers 1832, p. 545.

- ↑ Childs 1991, p. 229.

- ↑ Childs 1991, p. 345.

- ↑ Childs 1991, p. 285.

- ↑ Journals of the House of Commons, Volume 12. Great Britain House of Commons. 1803. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

Sources

- Argyll Transcripts, ICA (1891). "An Account of the depredations committed on the Clan Campbell and their followers during the years 1685 and 1686". Historical Manuscripts Commission. 11.

- Chandler, David; Beckett, Ian (1996). The Oxford History Of The British Army (2002 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280311-5.

- Childs, John (1987). The British Army of William III, 1689-1702 (1990 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719025525.

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719034619.

- Cobbett, William (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors (2011 ed.). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1175882448.

- Dalton, Charles (1896). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 V4.

- Guy, Alan (1985). Economy and Discipline: Officership and the British Army, 1714–63. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1099-6.

- Holden, Robert Mackenzie (October 1905). "The First Highland Regiment: The Argyllshire Highlanders". The Scottish Historical Review. 3 (9).

- Kennedy, Allan (2014). Governing Gaeldom: The Scottish Highlands and the Restoration State 1660-1688. Brill. ISBN 978-9004248373.

- Prebble, John (1973). Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140028973.

- Scott, Walter; Somers, John (1832). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III (2014 ed.). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1293842225.

- Walton, Clifford (1894). History of the British Standing Army 1660 to 1700 (2010 ed.). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1149754764.

External links

- Clan Campbell Society North America. "Official List of Septs of Clan Campbell". Clan Campbell Society. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Campsie, Alison (12 February 2018). "The Scotsman". Archaeologists trace lost settlements of Glencoe destroyed after 1692 massacre. Retrieved 3 July 2018.