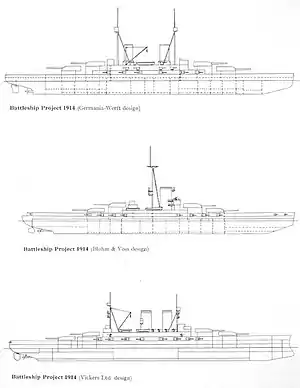

Three of the proposed designs: Germania's is on top, followed by Blohm & Voss' and Vickers'.[1] | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | None |

| Planned | 4 (9 originally proposed) |

| Completed | 0 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 184 m (604 ft) wl[2] |

| Beam | 28 m (92 ft)[2] |

| Draft | 9 m (30 ft) maximum[2] |

| Propulsion | Three shafts; six double-ended boilers; 38,000 shp giving a top speed of 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h); 2,400 t (2,400 long tons; 2,600 short tons) of fuel |

| Endurance | At least 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km)[3] |

| Complement | Approx. 860[3] |

| Armament | |

| Armor | |

| Notes | Specifications given above are for the Germania design |

A Dutch proposal to build new battleships was originally tendered in 1912, after years of concern over the expansion of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the withdrawal of allied British warships from the China Station. Only four coastal defense ships were planned, but naval experts and the Tweede Kamer (lower house of the parliament) believed that acquiring dreadnoughts would provide a stronger defense for the Nederlands-Indië (Netherlands East Indies, abbr. NEI), so a Royal Commission was formed in June 1912.

The Royal Commission reported in August 1913. It recommended that the Koninklijke Marine (Royal Netherlands Navy) acquire nine dreadnought-type battleships to protect the NEI from attack and help guarantee the country's neutrality in Europe. Five of these would be based in the colony, while the other four would operate out of the Netherlands. Seven foreign companies submitted designs for the contract; naval historians believe that a 26,850-long-ton (27,280 tonne) ship, whose design was submitted by the German firm Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft, would have been eventually selected.

The Royal Commission's proposal led to a debate between senior officers in the Navy and the Koninklijke Landmacht (Royal Netherlands Army) over how to best protect the NEI, and the question of how the cost of the ships should be split between the Netherlands and the NEI also was not settled until July 1914. After considering the recommendations, the Dutch Government decided to acquire four battleships, and a bill seeking funding for them was introduced into the Dutch parliament in August 1914. However, this was withdrawn following the outbreak of the First World War that month. A new royal commission into Dutch defense needs held after the war did not recommend that battleships be procured and none were ever ordered.

Background

During the early years of the 20th century, the Dutch became concerned about their ability to defend their colonial empire in the NEI from foreign aggressors. Fears of an eventual Japanese attack developed following the total defeat of the Russian Pacific and Baltic Fleets in the Russo–Japanese War.[4] Moreover, the withdrawal of most of the British China Station's warships in 1905 meant that there was no credible force in the Pacific to deter the Imperial Japanese Navy, which had been victorious over the Russians and was building powerful cruisers armed with 300 mm (12 in) guns.[5]

At the time, the Dutch naval force in the NEI, the Dutch Squadron in the East Indies, was widely seen as inadequate. It comprised a small number of destroyers, ironclads and armored cruisers, most of which were not battle-worthy.[6] In response to the perceived threat of Japanese attack, the Dutch laid down a coastal defense ship, De Zeven Provinciën, and eight destroyers of the Wolf class, while beginning plans for other ships. In addition, a submarine for the colony was approved in 1911.[7] Four coast defense ships were projected in one of the two major bills to come before the House of Representatives in 1912.[8][9] Specifications for these ships included an armament of four 280-mm (11-inch) and ten 102-mm (4-inch) guns and three torpedo tubes and they would have been armored with a belt of 152-mm (6-inch) and turret armor of 203 mm (8 inches). Two triple-expansion engines generating 10,000 indicated horsepower would drive the ships through the water at 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h).[8] One ship of this design was very close to being authorized in 1912, but it was felt by experts and the House of Representatives that the Netherlands would be better served by constructing dreadnoughts of a type similar to the Spanish España class.[7][8] Further plans for coast-defense ships were shelved pending the findings of a Royal Commission, formed on 5 June 1912.[5][8] Its goal was to assess the steps needed to improve the defenses of the East Indies.[5][8]

Meanwhile, in September 1912 the Navy Minister, Hendrikus Colijn, contacted the German firm Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft and asked them to prepare a design for dreadnought battleships suited to the NEI.[7] Germaniawerft submitted their design to the Royal Netherlands Navy on 25 September 1912.[10] The proposed ships were generally similar to the German Kaiser class, but with eight 343 mm (13.5 in) L/50 guns in four turrets mounted en echelon rather than ten 305 mm (12.0 in) guns in five turrets, and two fewer 150 mm (5.9 in) medium guns. The proposed Dutch ships were 1 knot (1.9 km/h) faster and had a longer range, at the expense of lighter armor protection, similar to that used in contemporary German battlecruisers. By the time the design was proposed the Dutch authorities had decided that mounting the armament en echelon was inferior to superfiring turrets, and asked Germaniawerft to submit a revised design incorporating this armament, enhanced ammunition storage and other minor improvements.[11]

Proposal

The Royal Commission handed its findings and recommendations to the government in August 1913. It concluded that international relations were deteriorating in the Pacific and there was an increased risk of the NEI becoming involved in a war between western and Asian powers. As a result, the Commission argued that the Netherlands should develop a powerful fleet of warships to enforce Dutch neutrality and offer a credible defense should any nation attack the NEI or the home country itself.[12] The Commission was very specific in its call for nine dreadnoughts, stating that they should be ships of 20,668 long tons (23,148 short tons; 21,000 t), possessing a speed of 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h), and mounting eight 340 mm (13 in) guns, sixteen 150 mm (5.9 in), and twelve 75 mm (3.0 in) guns.[2] It was also recommended that the fleet include six 1,200 long tons (1,300 short tons; 1,200 t) "torpedo cruisers"—believed by Conway's to be closer to large destroyers—eight 500 long tons (560 short tons; 510 t) destroyers (a role which would be filled by the Fret class), eight torpedo boats (also already completed, though they were old), eight large submarines and two large minelayers. This ambitious plan was estimated to cost nearly ƒ17,000,000 each year for the next 35 (until 1949), adding up to about ƒ595,000,000; this would triple the Navy's budget.[5] The Commission recommended that the cost of the fleet be partially offset by reducing the size of the Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger (Royal Dutch East Indies Army) as the Navy would provide a stronger defense from attack than the Army could.[13]

The requirement for nine battleships was determined by the defense needs of both the Netherlands and NEI. The Commission recommended that four battleships be active at all times in the NEI, with a fifth ship held in reserve there. The remaining four battleships would be based in the Netherlands. Ships sent to the NEI would return to Europe after twelve years in the tropics and complete another eight years service before being scrapped.[8][14]

The Dutch Navy would need a significant manpower expansion of 2,800 sailors to crew all of the proposed battleships. The Commission believed that it was unlikely that sufficient Dutch citizens would volunteer, and that as a result Indonesian sailors should be recruited and trained for service in the NEI. Strong segregation between white and Indonesian sailors was to be maintained to the maximum extent practical for unit efficiency.[15]

One member of the Commission, the chief accountant of the Ministry of Finance, A. van Gijn, objected to the report's conclusions. He provided a note to Queen Wilhelmina, which argued that advocates of building large warships had forced their views on the other members of the commission. Moreover, he believed that the proposed fleet would be inadequate given the rapid naval expansion being undertaken by the major powers, and that if it was adopted there would be a requirement to buy further dreadnoughts in order to keep pace. This note was included as an appendix to the Commission's report.[15]

The Royal Commission's proposals were extensively debated. Hendrick van Kol, who was one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Workers' Party, argued that building up a strong fleet would hinder Dutch neutrality by making it impossible to avoid battle with foreign fleets which passed through NEI waters en route to other destinations. Other critics of the plan believed that it would be unwise for the Netherlands to join the naval arms race which was taking place in Europe at the time, and that competition between the major powers meant that none of them would allow another nation to occupy either the Netherlands or the NEI. The Dutch Army also opposed the development of a strong fleet in the NEI, arguing that a land force centered on Java would be better able to mount a prolonged resistance against a large invasion force and that reducing the size of the Army to fund the fleet would leave it unable to suppress insurrections.[13] The Governor-General of the NEI, Alexander Willem Frederik Idenburg, argued that both a stronger Army and Navy were necessary, and advocated for seven battleships to be stationed in the Indies. He believed that the cost of this alternative could be managed by reducing the planned battleship force in European waters to three small ships.[16] Other supporters of the proposal, led by the Onze Vloot ("Our Fleet") naval advocacy association, argued that it was necessary to build a strong fleet which was capable of defending the NEI as the loss of the colonial empire would greatly damage the Dutch economy and reduce the country's prestige.[17] The Dutch Naval staff also debated the relative merits of torpedo boats and battleships, and concluded that while small craft and submarines were suitable for defending the Netherlands, large warships were needed to effectively protect the sprawling East Indies.[18]

After considering the Royal Commission's recommendations the Dutch Government decided to purchase four battleships. All the ships were to be permanently stationed in the NEI, and none would be used in European waters. The ships were larger than those proposed by the commission, however. Idenburg opposed this decision, and unsuccessfully argued for at least a fifth battleship to be built. In October 1913 it was rumored that the Government was about to order the first ship, and that it would be paid for by a loan borne by NEI.[19]

Design

Germaniawerft submitted a revised battleship design (designated Project No. 753) to the Dutch Navy on 4 March 1913, well before the Royal Commission reported back to the Government. As requested, the new design mounted its main armament in superfiring turrets. Other changes included an increase in the number of 150 mm (5.9 in) guns to sixteen, a 0.5 knots (0.93 km/h) faster maximum speed, different armor protection, replacement of two of the side-launching torpedo tubes with a single stern tube and an increase in the number of rounds carried for each gun from 60 to 100 for the main armament and 100 to 150 for the medium guns. The new design also had a single funnel and a tripod mast that supported a director tower. Displacement was increased from 19,535 tons to 20,040 tons.[20] Germaniawerft submitted a modified version of this design later in the year which increased the ships' displacement to 20,700 tons and substituted eight 343 mm (13.5 inch) L/45 guns mounted in two quadruple turrets which were better protected than the four double turrets in the Project No. 753 proposal. This design was not accepted, however.[3]

A meeting chaired by the Navy Minister, Jean Jacques Rambonnet, was held on 10 November 1913 to finalize the battleships' specifications. It was decided that the ships would be armed with eight 343 mm (13.5 inch) L/45 guns in four superfiring turrets mounted on the centerline, a secondary armament of sixteen 150 mm (5.9 inch) and twelve 75 mm (2.9 inch) guns and at least two, possibly four, 533 mm (21 inch) side-launching submerged torpedo tubes and a single stern torpedo tube. The ships were to have a speed of at least 21 knots (39 km/h) and an endurance of more than 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km) at 12 knots (22 km/h). They would be propelled by oil-fired boilers powering turbines and three or four propeller shafts. Armor protection would comprise a main belt at least 250 mm (9.8 inches) thick and at least 300 mm (11.8 inches) over the gun turrets and conning tower. A crew of 110 officers and petty officers and 750 ratings was envisioned, and designers were permitted to reduce the armor protection at ships' bow and stern to save weight for improvements to crew living conditions if necessary.[3]

On 13 March 1914 the Dutch Government altered the battleships' specifications to require a displacement of 25,000 tons, main armament of 356 mm (14 inch) guns, speed of 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h) and endurance of 6,000 nautical miles (6,900 mi; 11,000 km).[21] The specified speed was faster than normal for contemporary battleships and their belt armor protection was relatively thin. These characteristics were meant to aid the ships in fighting on the Java Sea; with the good visibility common in that area, naval battles could—and most likely would—be fought at a longer range than would be feasible in other areas like the North Sea, meaning that more shells would strike the deck rather than the belt.[2]

Eleven firms or groups of firms were invited to tender to build the ships, with proposals due on 4 June 1914. Proposals were received from seven firms; Germaniawerft, Blohm & Voss, AG Vulcan in cooperation with Bethlehem Steel and AG Weser from Germany as well as the British firms Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co, Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company and Vickers. It is believed that Armstrong submitted at least five different designs.[21] As Dutch shipyards lacked the capability to build large battleships, the ships would have been constructed abroad.[22]

The proposal from Germaniawerft (designated Project No. 806) is regarded by both Conway's and historian Anthonie van Dijk as being the most likely to have been selected.[2][23] This design envisioned 24,605 long ton ships with a length of 184 meters (604 ft), beam of 28 meters (92 ft) and draft of 9 meters (30 ft).[2] The main armament of eight 356 mm guns was to be mounted in four superfiring turrets, while the sixteen 150 mm guns would be placed in casemates about 6 meters (20 ft) above the waterline. Their machinery would include six double-ended boilers and one single-ended boiler and three turbine sets were to drive three propeller shafts.[21] Armor would have included a belt of 250 mm amidships and 150 mm to fore and aft.[8][N 1] Germaniawerft reserved the right to subcontract Blohm & Voss to build some of the ships and offered a delivery time for the first ship of 28 months following the date the order was made.[21]

Other major proposals included the ones from Blohm & Voss and Vickers. While both included the same armament as Germania, the former design had a smaller displacement—26,055 long tons (26,473 metric tons) versus 28,033 long tons (28,483 t)—and devoted a greater amount of weight to protection: 8,974 long tons (9,118 t, 34.8% of the displacement), versus 8,820 long tons (8,960 t, 31.77%). Blohm & Voss' design included a belt starting at 150 mm in the bow, increasing to 250 mm, then tapering to 100 millimeters (3.9 in) in the stern. It would have been powered by six double-ended coal boilers with oil burners alongside. These boilers would have generated 38,000 shaft horsepower (shp) to drive four propellers, giving the ships a maximum speed of 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h). Only one rudder would have been fitted. The Vickers design had a shorter belt of 250 mm amidships, and would have used 15 boilers with oil burners to provide 34,000 shp and the same 22 knots.[8][N 2]

Weight distribution

| Component[N 3] | Germaniawerft[8] | Blohm & Voss[8] | Vickers[8] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hull | 7,554 long tons (7,675 t), 28.45% | 7,510 long tons (7,630 t), 29.20% | 8,535 long tons (8,672 t), 30.76% |

| Armor | 9,310 long tons (9,460 t), 34.97% | 8,974 long tons (9,118 t), 34.8% | 8,820 long tons (8,960 t), 31.77% |

| Engines | 2,160 long tons (2,190 t), 8.14% | 2,074 long tons (2,107 t), 7.96% | 2,406 long tons (2,445 t), 8.67% |

| Armament | 3,565 long tons (3,622 t), 13.43% | 3,699 long tons (3,758 t), 10.46% | 3,415 long tons (3,470 t), 12.31% |

| Fuel | 2,362 long tons (2,400 t), 8.89% | 2,982 long tons (3,030 t), 11.55% | 2,952 long tons (2,999 t), 10.64% |

| Equipment | 1,624 long tons (1,650 t), 6.12% | 1,555 long tons (1,580 t), 6.03% | 1,625 long tons (1,651 t), 5.85% |

| Weight margin | 275 long tons (279 t) | 261 long tons (265 t) | 280 long tons (280 t) |

| Total displacement | 26,850 long tons (27,280 t), 100% | 26,055 long tons (26,473 t), 100% | 28,033 long tons (28,483 t), 100% |

Debate over costs

There was an extensive debate over how to divide the cost of the proposed fleet between the Netherlands and NEI. The members of the Royal Commission were split on this question; while a minority preferred an equal division, the majority wanted the NEI to pay most of the costs.[24] The public debate on this issue was centered on the questions of who should pay for the ships and who would make the greatest profits from the NEI remaining under Dutch rule. Arguments against the NEI paying for the ships included that the resources required were needed to fund economic and social development and that the cost of the ships would increase opposition to Dutch rule, thereby worsening the security situation in the East Indies. Some critics of the plan also argued that it was unreasonable to expect the Dutch subjects in the NEI to pay for ships intended to prolong colonial rule.[25] In contrast, Onze Vloot published pamphlets which claimed that Dutch rule was seen as beneficial in the NEI, and that both white and Asian residents of the islands would be willing to pay for the ships as they were necessary to guarantee its continuation. These pamphlets also argued that the cost of the ships was modest compared to the NEI's economic output.[26]

In order to avoid a confrontation over the naval budget, the Dutch Government postponed parliamentary discussions of the Royal Commission's recommendations during 1913 and early 1914.[27] By this time Onze Vloot's campaign in support of the fleet had gained considerable momentum.[28] In late 1913 the Government accepted an offer made by representatives of the Dutch business community to contribute 120,000 guilders towards the cost of a second battleship once parliament approved funding for the first ship. Despite this, the Government continued to delay submitting a plan for the defense of the NEI to parliament, though work continued on it. The main difficulty remained the question of how to pay for the fleet. The Minister of the Colonies, Thomas B. Pleyte, believed that the NEI's population needed to be sheltered from the cost of the ships to the extent possible so that funding for welfare projects was not reduced or taxes increased from what were already high levels. In 1914 he settled on a plan under which the necessary revenue would be raised through increasing the taxes on export duties and freight moved by privately owned railways and ships.[29]

A bill setting out arrangements for funding and building the fleet was finalized in mid-July 1914.[22] At this time the Navy had not yet settled on a final battleship design.[23] It was planned that the first ship's keel would be laid in December 1914 and fitting out be completed sometime in 1918.[30] The bill was not immediately introduced into parliament, however, as Idenburg was given until 10 August to comment on it. The outbreak of the First World War led to the bill being withdrawn due to the uncertain international circumstances and the impossibility of buying battleships from foreign shipbuilders in wartime.[31] Instead, the Government ordered three Java-class cruisers in 1915, though only two were completed.[32][33]

Aftermath

Twice in its history did the Netherlands navy plan the construction of capital ships. In both cases this occurred immediately prior to the outbreak of world wars.[34]

A new Royal Commission into the defense of the Netherlands and NEI was held during 1920 and 1921. This Commission did not recommend that any battleships be constructed; instead it proposed that all ships under construction as at 31 December be completed along with a further two cruisers, 12 destroyers and 16 submarines. This plan was considered unaffordable, however, especially given the strength of the disarmament movement internationally.[35] A Navy Bill to fund a reduced version of the Royal Commission's proposal was introduced to parliament in November 1921, but was eventually defeated by a single vote in October 1923.[35][36] Renewed Dutch concerns over Japanese aggression in the late 1930s led to a proposal to build three Design 1047 battlecruisers for service in the NEI, but construction of these ships had not begun when the Netherlands was overrun by German forces in May 1940.[37]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Other armor specifics for the Germaniawerft design included (in mm; question marks denote unknown values): armored transverse bulkheads: 200, 200; citadel armor: 180; deck armor: 25, 25, 25–50 (deck above casemates, deck containing casemates, main armor deck); torpedo bulkhead: 40, barbettes 300–110 (top to bottom); turrets: ?, ?, ?; conning tower: 300, 300 (fore, aft).[8]

- ↑ Other armor specifics for the Blohm & Voss and Vickers designs included: armored transverse bulkheads: ?, ? (B&V)/150, 100 (V); citadel armor 180/180; deck armor 27, 25, 30/37, 37, 25; torpedo bulkhead 30/37; barbettes 300–75/200–120–50; casemates 180/?; conning tower 300, 150/300, 300.[8]

- ↑ The percentages are how much weight each component would have taken out of the final displacement.

Citations

- ↑ Breyer, Battleships and battle cruisers, 453

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Sturton, "Netherlands", 366

- 1 2 3 4 van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III., 396

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 73–75

- 1 2 3 4 Sturton, "Netherlands", 363

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 95

- 1 2 3 van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part I., 359

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Breyer, Battleships and battle cruisers, 452

- ↑ Claflin, ed., "Holland and Belgium", 322b

- ↑ van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part II., 30

- ↑ van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part II., 35

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 100–101

- 1 2 van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 103–105

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 101

- 1 2 van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 102

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 106

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 111–112

- ↑ Abbenhuis, The Art of Staying Neutral : The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914–1918, 52–53

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 108

- ↑ van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III., 395–396

- 1 2 3 4 van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III., 399

- 1 2 van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 123

- 1 2 van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III., 402

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 101–102

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 108–109

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 119–120

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 110

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 117

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 121–123

- ↑ Sturton, "Netherlands", 363 and 366

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 123–124

- ↑ van Dijk, The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III., 402–403

- ↑ Sturton, "Netherlands", 367

- ↑ Breyer, Battleships and battle cruisers, 451

- 1 2 Sturton, "Netherlands", 364

- ↑ van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918, 124

- ↑ Breyer, Battleships and battle cruisers, 454

References

- Abbenhuis, Maartje M. (2006). The Art of Staying Neutral : The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914–1918. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-818-2.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers, 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 702840.

- Clafin, W. Harold (1916). "Holland and Belgium". In Lodge, Henry Cabot (ed.). The History of Nations. Vol. 13 (4 ed.). New York: P.F. Collier and Son. OCLC 4016415.

- Sturton, Ian (1984). "Netherlands". In Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3. OCLC 12119866.

- van Dijk, Anthonie (1988). "The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part I.". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: The International Naval Research Organisation. XXV (4). ISSN 0043-0374.

- van Dijk, Anthonie (1989). "The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part II". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: The International Naval Research Organisation. XXVI (1). ISSN 0043-0374.

- van Dijk, Anthonie (1989). "The Drawingboard Battleships for the Royal Netherlands Navy. Part III". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: The International Naval Research Organisation. XXVI (4). ISSN 0043-0374.

- van Dijk, Kees (2007). The Netherlands Indies and the Great War 1914–1918. Volume 254 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: KITLV Press. ISBN 978-90-6718-308-6.