The Dunbar–Hunter Expedition of 1804–1805 was an expedition led by William Dunbar and George Hunter with the purpose of exploring the lower portion of the Louisiana Purchase. The expedition was given the orders by Thomas Jefferson to explore parts of Mississippi and Missouri.[1] The members of the expedition recorded information about the Ouachita River, and studied things such as the hot springs in modern-day Arkansas and provided one of the earliest descriptions of Arkansas and Louisiana.[1]

Preparations

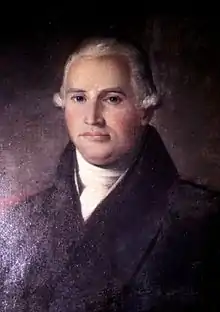

William Dunbar was a Scottish immigrant and scientist living in Natchez, Mississippi, when Jefferson contacted him about the proposed expedition.[2] Jefferson wanted the expedition to travel through the southern area of the Louisiana Purchase. Specifically, he wanted the expedition to follow the rivers in the area, such as the Red River or the Arkansas River.[3] The other leading member of the expedition, George Hunter, was recruited by Jefferson and was instructed to "make observations, to note courses," and to study the same things as Dunbar, but to keep his own account in case their observations differed from one another.[4] In 1804, a boat was built for the expedition to travel down the Red River, however the expedition's plans were changed in order to travel to the hot springs instead after receiving word that their initial plans might result in conflict between the expedition and a band of the Osage tribe living in the region.[4] With the new plan now in mind, the expedition left in October 1804.[4]

Journey

The members of the expedition departed on their journey at a location on the Mississippi River named St. Catherine's Landing.[1] The members numbered 19 in total, including people who were not formal members of the expedition such as Hunter's son, two slaves, and a servant.[1] Hunter designed the boat that was used on the journey, which resembled a scow and was referred to by members of the expedition as a "Chinese-style vessel."[1] According to George Hunter's writings in the journal he kept during the expedition, the group traveled down the Red River, as well as the Black River and Ouachita River, eventually landing at the hot springs.[4] The members of the expedition were making observations of the land, people, and waters they encountered along the way, and turned back at the hot springs in order to return to where they began their expedition. Dunbar reportedly left the party around Fort Miro in order to take a land route to his home, where he would share the expedition's findings with the government via a transcript of his journal.[4] The remaining members of the group continued their return to St. Catherine's Landing, where the journey was concluded in January 1805.[1]

Discoveries

The Hunter–Dunbar Expedition produced discoveries and records relating both to scientific observations and to observations of Native people living in the areas which were explored. Many observations were made by both Hunter and Dunbar at the hot springs of Arkansas, such as Hunter's study of the water quality in the springs and the efforts by Dunbar to calculate the total rate of discharge of the springs.[5] Microorganisms were also discovered in the hot springs by members of the expedition.[3] The expedition also produced some of the earliest records written in English about the geographical features of Arkansas and Louisiana.[1] Additionally, records of natural aspects such as plant and animal life in the region around the Ouachita River were kept by Hunter and Dunbar.[1]

The records kept of people in the region included details not only of indigenous people in the region, but also of fur traders, trappers, and other European travelers populating the area.[1] They provided a description of the relationships between the people located in this region, as well as how these people used the natural resources around them.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Berry, Trey (2003). "The Expedition of William Dunbar and George Hunter along the Ouachita River, 1804-1805". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 62 (4): 386–403. doi:10.2307/40023081. JSTOR 40023081.

- ↑ Clements, Jeanne; Beasley, Pam; Berry, Trey, eds. (2014). "Editors' Introduction". The Forgotten Expedition, 1804–1805: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter. Louisiana State University Press. pp. xi–xxxvi. ISBN 978-0-8071-5974-3. Project MUSE chapter 1326492.

- 1 2 "William Dunbar". Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McDermott, John Francis (1959). "The Western Journals of George Hunter, 1796-1805". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 103 (6): 770–773. JSTOR 985390.

- ↑ Hanor, Jeffrey S. (November 2007). "The Dunbar‐Hunter Expedition (1804–1805): Early Analyses of Spring Waters in the Louisiana Purchase". Groundwater. 45 (6): 803–807. Bibcode:2007GrWat..45..803H. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.2007.00364.x. PMID 17973760. S2CID 42652870.