| Mary | |

|---|---|

%252C_by_Netherlandish_or_South_German_School_of_the_late_15th_Century.jpg.webp) Portrait (c. 1490) possibly painted by Michael Pacher | |

| Duchess of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482 |

| Predecessor | Charles I |

| Successor | Philip IV |

| Alongside | Maximilian |

| Born | 13 February 1457 Brussels, Brabant, Burgundian Netherlands |

| Died | 27 March 1482 (aged 25) Wijnendale Castle, Flanders, Burgundian Netherlands |

| Burial | Church of Our Lady, Bruges, Belgium |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Valois-Burgundy |

| Father | Charles the Bold |

| Mother | Isabella of Bourbon |

Mary of Burgundy (French: Marie de Bourgogne; Dutch: Maria van Bourgondië; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), nicknamed the Rich, was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy who ruled a collection of states that included the duchies of Limburg, Brabant, Luxembourg, the counties of Namur, Holland, Hainaut and other territories, from 1477 until her death in 1482.[1][2][3]

As the only child of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and his wife Isabella of Bourbon, Mary inherited the Burgundian lands at the age of 19 upon the death of her father in the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477.[4] In order to counter the appetite of the French king Louis XI for her lands, she married Maximilian of Austria, with whom she had two children. The marriage kept large parts of the Burgundian lands from disintegration, but also changed the dynasty from Valois to Habsburg (the Duchy of Burgundy itself soon became a French possession).[5][6] This was a turning point in European politics, leading to a French–Habsburg rivalry that would endure for centuries. Long after Mary's death, her husband became Holy Roman Emperor. Their son became King Philip I of Castile, and their daughter, Margaret, became Duchess of Savoy.

Early years

Mary of Burgundy was born in Brussels at the ducal castle of Coudenberg, to Charles the Bold, then known as the Count of Charolais, and his wife Isabella of Bourbon. Her birth, according to the court chronicler Georges Chastellain, was attended by a clap of thunder ringing from the otherwise clear twilight sky. Her godfather was Louis, Dauphin of France, in exile in Burgundy at that time; he named her for his mother Marie of Anjou. Reactions to the child's birth were mixed: the baby's grandfather, Duke Philip the Good, was unimpressed, and "chose not to attend the [baptism] as it was only for a girl", whereas her grandmother Isabella of Portugal was delighted at the birth of a granddaughter.[7] Her illegitimate aunt Anne was assigned to be responsible for Mary's education and assigned Jeanne de Clito to be her governess. Jeanne remained a friend to Mary later in life and was one of her most constant companions.

Heir presumptive

Philip the Good died in 1467 and Mary's father assumed control of the Burgundian State. Since her father had no living sons at the time of his accession, Mary became his heir presumptive. Her father controlled a vast and wealthy domain made up of the Duchy of Burgundy, the Free County of Burgundy, and the majority of the Low Countries. As a result, her hand in marriage was eagerly sought by a number of princes. The first proposal was received by her father when she was only five years old, in this case to marry the future King Ferdinand II of Aragon. Later she was approached by Charles, Duke of Berry; his older brother, King Louis XI of France, was intensely annoyed by Charles's move and attempted to prevent the necessary papal dispensation for consanguinity.

.jpg.webp)

As soon as Louis succeeded in producing a male heir who survived infancy, the future King Charles VIII of France, Louis wanted him to be the one to marry Mary, even though he was thirteen years younger than Mary. Nicholas I, Duke of Lorraine, was a few years older than Mary and controlled a duchy that lay alongside Burgundian territory, but his plan to combine his domain with hers was ended by his death in 1473 (he started having stomach pains three days before his death; poison was suspected).[8] Another suitor was George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (supported by his sister Margaret of York), but his brother Edward IV, King of England, prevented the match for both political and personal reasons (he initially wanted to support his brother-in-law Anthony Woodville). The king's move angered the duke, who seemed to lose control and restarted conflicts with his brother, which ultimately led to his death.[9][10]

Reign

Mary assumed the rule of her father's domains upon his defeat in battle and death on 5 January 1477. King Louis XI of France seized the opportunity to attempt to take possession of the Duchy of Burgundy proper and also the regions of Franche-Comté, Picardy and Artois.

She called on her people to stay loyal to the house of Burgundy (there are still extant letters that Mary wrote to the Duchy of Burgundy and Arras asking for their support).[11] Louis XI took over Arras, but the people refused to submit without her approval. Eighteen burgesses were decapitated by the king as they were discovered trying to go to see her. He ordered a mass expulsion and renamed the town Franchise.[12]

The king of France was anxious that Mary should marry his son Charles and thus secure the inheritance of the Low Countries for his heirs, by force of arms if necessary. By February 1477, neither her advisors nor the States General imagined that they could resist the French army. Chancellor Hugonet led a delegation to discuss the prospect of Mary's marriage to the six-year-old Dauphin (later King Charles VIII). The negotiation ended in failure as Louis XI demanded unacceptable terms, including the surrender of the Duchy of Burgundy and the French territories acquired by Philip the Good and Charles the Bold. The king then betrayed her secret letters to the burghers of Ghent, who then seized two men who were named in those letters – Hugonet and the Sire d'Humbercourt, two of her father's most influential councilors, and despite her pleadings, executed them on 3 April 1477. They then took away her other advisors too.[13][14] Koenigsberger suspects that Louis XI might have forged the letters.[15]

The Great Privilege

Mary was compelled to sign a charter of rights known as the Great Privilege in Ghent on 10 February 1477, the occasion of her formal recognition as her father's heir (the "Joyous Entry"). Under this agreement, the provinces and towns of Flanders, Brabant, Hainaut, and Holland recovered all the local and communal rights that had been abolished by the decrees of the dukes of Burgundy in their efforts to create a centralised state on the French model out of their disparate holdings in the Low Countries. In particular, the Parliament of Mechelen (established formally by Charles the Bold in 1470) was abolished and replaced with the pre-existing authority of the Parlement of Paris, which was considered an amenable counterweight to the encroaching centralisation undertaken by both Charles the Bold and Philip the Good. The duchess also had to undertake not to declare war, make peace, or raise taxes without the consent of these provinces and towns and only to employ native residents in official posts.

Marriage

_zu_Inschrift_1_1477_Heirat_Erzherzogs_Maximilians_I_mit_Maria_von_Burgund._Bildvorlage_Ehrenpforte_-_..._Pictura_poterit_manere_eadem_quae_antea_in_Porta_honoris_(SInnsbruck_1_.jpg.webp)

Mary soon made her choice among the many suitors for her hand by selecting Archduke Maximilian of Austria (future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I), who became her co-ruler.[16] The marriage took place at Ghent on 19 August 1477, she was 20 years old, while he was two years younger.[17] Mary's marriage into the House of Habsburg initiated two centuries of contention between France and the Habsburgs, a struggle that climaxed with the War of the Spanish Succession in the years 1701–1714.

When they had time, the couple indulged themselves with dancing, hunting, music and the love for animals. Mary tried to teach him iceskating, which he struggled to master. They read romances together.[19][20] Soon after the wedding, she brought falcons into their bedroom (which they shared instead of living in separate apartments, and which already had a dog).[21] Mary nursed the children herself, ordered the menus and dined out with merchants from Dijon.[22][23] Mary cheered for her husband in tournaments, during which he proved a magnificent jouster, not just in feats of strength but in the luxury he lavished on the equipments, horses, accessories and ornaments as well.[24][25] At first, they talked to each other in Latin.[26]

According to Haemers and Sutch, the original marriage contract stipulated that Maximilian could not inherit her Burgundian lands if they had children – this means that, the fact the couple produced heirs would give Maximilian troubles later.[27][28] Some report that the original marriage contract stipulated that only common children of Mary and Maximilian could claim her Burgundian inheritance after her death. But one month after their marriage, she made an amendment that designated Maximilian as the heir in the case they had no children - a clause that the estates would try to repudiate after her death.[29][30]

Co-rule with Maximilian

With Maximilian by her side, Mary's position became stronger, politically and militarily. Although he came with no money nor army, nor support from the Empire, and no prior experience in governance, his competence in military matters and his prestige as the son of an emperor boosted the stability of her realms. He took over the war effort, concerning both military and financial details.[31]

By this time, the Burgundian side had lost a lot of military captains owing to defections to France both before and after Charles the Bold's death. The loss of the Duchy of Burgundy cut down the whole government's backbone, consisting of high administrators and military commanders who came from the French-speaking nobility in Burgundy and Picardy.[32][33] Philip of Cleves, her cousin and childhood friend (who had been put forth as a bridegroom candidate for Mary by his father Adolf of Cleves; Mary and Philip were rumoured to be former love interests, although this is disputed by Arie de Fouw), whom she appointed as Stadtholder-General in 1477, now acted as Maximilian's lieutenant as Admiral of the Netherlands.[34][35] Despite the reputation of the Burgundian court as luxurious and rich, Charles the Bold had lost his whole fortune in his last three disastrous campaigns. The Low Countries were rich but the Estates were reluctant to pay. Moreover, the Burgundian state had lost one quarter of its tax revenue and due to new restrictions, a half of its government revenue in total.[32] Thus the initial financial situation was very tense and Mary had to pawn a lot of her heirlooms to finance their armies.[36] She also had to yield to the estates' demands regarding some of their privileges, in exchange for final support for Maximilian's war against France.[37]

Violet Soen shows that by political manipulation, Mary managed to tie the powerful Croÿ family to the crown.[38]

Mary would not gain back the Duchy of Burgundy, occupied by the French king, but she was able to keep her remaining lands intact.[39][40][41] In 1478–1479, Maximilian carried out a campaign against the French and reconquered Le Quesnoy, Conde and Antoing.[42] He defeated the French forces at Guinegate (modern Enguinegatte), on 7 August 1479.[43] Despite winning, he had to abandon the siege of Thérouanne and disband his army, either because the Netherlanders did not want him to become too strong or because his treasury was empty. In addition, he proved as ruthless as Charles in suppressing rebellions in the Low Countries.[44] When conflicts broke out again between the Hooks and the Cods, the archduke was able to put the conflict under control and assured the Cod domination, disregarding the Great Privilege in the process.[45] After a five-year hiatus (because most of the members had either died in Charles the Bold's wars or defected to France),[46] the Order of the Golden Fleece also got reorganized by Maximilian, as the new sovereign of the order.[47]

However, within the marriage, Mary retained her political primacy. Her subjects looked at Maximilian's foreigner status and his military ambitions with suspicion. They feared that he would prolong the war to regain the Duchy of Burgundy,[48] and also that new successes would strengthen him and make him a second coming of Charles the Bold, whose legacy had left them with a feeling of distaste – a fear that would prove not unreasonable, considering his autocratic and militaristic tendencies during his later regency.[49] Moreover, according to Philippe de Commines, Maximilian was too young, in a foreign land, had been "brought up very badly" and thus did not have the slightest idea how to conduct affairs of the state.[50] Mary and Margaret tried to teach him French and Dutch but he proved a lazy student. Mary accompanied Maximilian on his many journeys, acting as the buffer between the German-speaking prince and their subjects.[51] According to Juan Luis Vives, a near contemporary author, when her subjects approached her on political matters, she would consult her husband "whose will she regarded as law", but she was always able to administer everything according to her own wishes and Maximilian, a mild husband, would never oppose her will.[52] She managed internal affairs and attended all assemblies where the couple needed to raise revenue. Burgundian coinage showed that Maximilian was never endowed with the official rank that contemporary royal husbands such as Ferdinand of Aragon achieved in their wives' possessions.[53] Apparently, she could impose her will on her spouse in military matters as well, as shown in the two times she tried to do this. In one case, recounted by Maximilian in the manuscript of the Weisskunig, his advisors tried to prevent him from unleashing war against a stronger French army who had concentrated at the front, but he was determined to carry it out. The advisors asked for help from Mary, who told him he could go but should come back to say farewell to her first. When he went back, she had him promptly locked up in his own apartment. After long negotiations, he agreed to go dancing instead and was let out.[54] In her official images and presentation, she was presented as an active, commanding ruler, usually on horseback and with a hawk. She adopted a more pacifistic image than her father, but her position as the rightful ruler was emphasized while Maximilian, armored and armed, tended to be shown behind his wife. This was in contrast with the profile portraits that Maximilian commissioned during his later reign as emperor, where she was often shown as the passive side.[55]

In order to bolster support for the government, she focused the most on public appearances, especially public shows of piety.[56][57]

The 1482 winter was harsh and France had declared a salt blockade, but the political situation in the Netherlands was overall positive; the French aggression was temporarily checked, and internal peace was in large measure restored.[58]

Towards the end of her rule, there was an event that exarcebated the division between the central government and other factions: the murder of Jehan (or Jan) van Dadizeele on 20 October 1481. At the time, there were angry accusations against Maximilian and Lord of Gaasbeek, one of his closest counsellors.[59][60] In 2023, a letter written by Frederik van Horn and preserved at the Gelders Archief (found by Haemers and van Driel) shows that van Horn was the person who committed the murder. According to van Horn, after the murder of Dadizeele, Mary wrote a letter to him, declaring that Dadizeele was a villain and a traitor who tried to replace her and Maximilian's faithful servants with the people he chose, as he saw fit, and that she would see the killing as revenge for herself. Haemers opines that she herself seemed to be preparing to kill Dadizeele (in the case van Horn was honest about Mary's letter – at the time, he was trying to justify his act and get a pardon), but in reality, was not the perpetrator. Ultimately, Mary chose to pardon and defend Frederik van Horn. This decision would later help to lead to the Flemish revolts against Maximilian (1482–1492).[61]

Death and legacy

In 1482, a falcon hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle was organised by Adolph of Cleves, Lord of Ravenstein, who lived in the castle. Mary loved riding and was hunting with Maximilian and knights of the court when her horse tripped, threw her in a ditch, and then landed on top of her, breaking her back. She died several weeks later on 27 March from internal injuries, having made a detailed will. She was buried in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges on 3 April 1482. She was pregnant.[lower-alpha 1]

Maximilian was devastated. She had initially hidden the extent of her injury to calm him down. When he continued to display uncontrollable grief, she had to force him out of her chamber so that she could discuss matters of the state with her nobles, concerning which she asked them to keep their loyalty oath to him and their children. Maximilian was not present when she said her last words.[66][67]

The bankrupted court honoured her with a glorious funeral, as Maximilian melted down the silverware for the occasion.[68]

Her two-year-old daughter, Margaret of Austria, was sent in vain to France, to marry the Dauphin, in an attempt to please Louis XI and persuade him not to invade the territories owned by Mary.

Louis was swift to re-engage hostilities with Maximilian and forced him to agree to the Treaty of Arras of 1482, by which Franche-Comté and Artois passed for a time to French rule, only to be recovered by the Treaty of Senlis of 1493, which established peace in the Low Countries. Mary's marriage into the House of Habsburg proved to be a disaster for France because the Burgundian inheritance later brought it into conflict with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1493, Emperor Frederick III died. Maximilian became the de facto leader of the Empire and relinquished control of the Netherlands to his and Mary's son Philip. By this time, rebellions against Maximilian's authority had been subdued by force and a strong ducal monarchy was established. He made sure that during their son's inauguration, Philip confirmed only the rights granted to territories by the time of Philip the Good.[69]

Olga Karaskova summarizes scholarly opinions on Mary's rule as follows:

Mary of Burgundy as ruler seems to be rather a non sequitur topic for a study as her short reign — sandwiched between those more important of her belligerent father, Charles the Bold, and her imposing spouse, Maximilian of Austria — is often marginalized by researchers. A somewhat ambiguous figure, whose image hovers somewhere in the space limited by two opposing concepts — an inexperienced and weak duchess, a mere pawn in the great political game played between France and the Holy Roman Empire, and a self-determined young princess who knew what she wanted and managed to dictate her will, praised by her biographers, Mary still remains generally in the shade of her nearest kinsmen despite the abundant publications concerning the Duchy of Burgundy.[70]

In 2019, she was added to the Canon of the Netherlands. The committee headed by James Kennedy explained that, "her Habsburg marriage determined the international position of the Netherlands for centuries." and that "her personality and the leniency of her government" preserved "the unity of the core regions of the Burgundian Netherlands.", even if most of the functions of the head of state were carried out by the energetic husband.[71][72] Historian Jelle Haemers opines that she should not be made into a feminist icon.[73]

Maximilian tended to describe Mary as the Grand Dame, who could stand next to him as sovereigns.[74][75] The devotion the people of the Low Countries had towards Mary (often idealized as earthly representation of the Virgin Mary) helped Maximilian, their children and the central government in the turbulent period following her death.[76][lower-alpha 2]

In arts and popular culture

Arts and legends under the rule of Mary, Maximilian and the Habsburgs

- The Faust legend is strongly based on a legend involving Mary, Maximilian and the priest, abbot and humanist Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), who was suspected by many to be a necromancer. Through his 1507 account, Trithemius was the first author who mentioned the historical Doctor Faustus. Being summoned to the emperor's court in 1506 and 1507, he also helped to "prove" Maximilian's Trojan origins. In his 1569 edition of his Tischreden, Martin Luther writes about a magician and necromancer (understood to be Trithemius) who summoned Alexander the Great and other ancient heroes, as well as the emperor's deceased wife Mary of Burgundy, to entertain Maximilian.[79] In his 1585 account, Augustin Lercheimer (1522–1603) writes that after Mary's death, Trithemius was summoned to console a devastated Maximilian. Trithemius conjured a shade of Mary, who looked exactly like her likeness when alive. Maximilian also recognized a birthmark on her neck, that only he knew about. He was distraughted by the experience though, and ordered Trithemius never to do it again. An anonymous account in 1587 modified the story into a less sympathetic version. The emperor became Charles V, who, despite knowing about the risk of black magic, ordered Faustus to raise Alexander and his wife from death. Charles saw that the woman had a birthmark, that he had heard about.[80] Later, the woman in the most well-known story became Helen of Troy.[81]

In her lifetime, Mary's preferred symbols, which were often associated with her official image, were the falcon and the horse. Ann M.Roberts notes that the falcon seemed to be a substitute for the sword (which was used by her grandfather and father for their seals), that denoted her status and prowess and also seemingly equated her skills as a huntress with her husband's skills as a military leader.[83] Also according to Roberts, the posthumous portraits produced during her husband's later reign (which were much more numerous) show a completely different image: he tended to utilize the profile portraits that portrayed her as a young (with less personal features and only recognizable by her items, such as the hennin, the brocaded garment, necklaces and brooches), virtuous, pious, passive bride whose wealth he possessed and could do with as he wanted and for whom he constructed a mythology of romantic love between the two.[84]

Olga Karaskova also opines that the manner she was placed in the premier position and her seal superimposed on his in their seals seems to indicate the conception she had of herself and the way she wanted to be seen by her contemporaries.[85] During Maximilian's later reign, he commissioned numerous portrayals of Mary for various purposes. According to Karaskova, the symbol of the falcon did not disappear, but returned as Maximilian needed to assert his and their descendants' right of inheritance. In public portraits, the image of Mary holding a falcon returned once during the inauguration of Charles V. In addition, Maximilian commissioned portraits of Philip the Fair and Charles V holding falcons (thus establishing a connection between them and Mary), so he had to depend on the iconography created by Mary and associated with her, that had not been erased from the memory of their contemporaries. In the Old Prayer Book of Maximilian of Austria (l'Ancien livre de prières de Maximilien d'Autriche, 1486, Vienne, ÖNB, Cod. 1907, f. 61v), there are the depiction of three falcons that seemingly symbolize Mary, Philip the Fair and Maximilian: Mary was with Philip while Maximilian was chasing another bird, symbolically protecting wife and child, next to the German eagle and the combined coat-of-arms of the Houses of Austria and Burgundy.[86] Maximilian also had a tendency to virtually "promote" Mary to the status of Empress in these posthumous portrayals: an image created by Jörg Kölderer in preparation for Mary's statue in Maximilian's cenotaph showed a coat-of-arms that incorporated her husband's symbols as King of the Romans or Holy Roman Emperor (that she could not have used in life).[87]

There was also a type of iconography created for the emperor's private use (instead of being used as a political declaration to the public), created by Bernhard Strigel: Mary, also presented in the imperial style as his empress, queen Ehrenreich and eternal companion, was shown with falcons outside the window and a hunting scene on her corsage, which seemed to imply courtly love and the days of happiness for the emperor. This iconography also seemed to be connected to the diptych Portrait of Emperor Maximilian and his family by Bernhard Strigel (mentioned below).[89]

In the Book of Hours of Mary and Maximilian (Berlin, SM, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms. 78 B 12, f. 220v.), the falcon and the hunt scene were shown, not as display of political significance, but only tragedy. Karaskova suggests that the coincidence that combined the Duchess's favourite mode of portrayal and the manner of her death must have had an impact on the illustrator as well as the commissioner, in this case Maximilian.[90][91][92] According to the documentary Der letzte Ritter by Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF), in his conversations with their daughter Margaret, the emperor associated the call of the falcon with "the blackest day of his life" (he remained a passionate falconer though – In his cenotaph, where there are also Mary's and his statues, the belt of Mary's grandfather, Philip the Good, displays the image of a male falconer and a female falconer).[75][93]

Karaskova comments that the type of profile portraits that Roberts considers to be the products of Maximilian's preferences (which also presented her as youthful and wealthy) seemed to have existed and been copied since her lifetime and connected her to her ancestors, especially Philip the Bold, who also had such profile portraits.[94] After his marriage to Bianca Maria in 1494, Maximilian also presented himself with both of his wives simultaneously. There was a notable tendency, expressed most clearly in the representations of genealogical trees (one commissioned in 1497, and another ten years later): outwardly, the group looked united, but Maximilian turned his back on Bianca to face the mother of his children (Unterholzner also notes that Maximilian always concentrated on the children of his first marriage in terms of succession politics, despite the fact that this was very risky; later, as the mother of his only (legitimate) children, Mary of Burgundy only became more important).[95][96]

Later, her children Philip and Margaret preferred to utilize the images of the undisputed dukes (which were shown in public spaces) instead of those of the disputed duchess to consolidate their rule, but that does not mean they displayed emotional disavowal towards her, as shown by the famous diptych commissioned by Margaret to commemorate her mother and created by Jan Mostaert in 1520.[97] Charles V, however, focused on his paternal ancestors, especially on Maximilian and Mary as true progenitors of his house.[98] The falcon also returned and her role as Duchess of Burgundy was also highlighted.[99]

- The massive semi-autobiographical works (commissioned by Maximilian, who was also likely their main author[100]) like the epic poems Theuerdank and Freydal, and the chivalric novel Weisskunig are in parts tribute to their love and marriage. As Queen Ehrenreich (Rich in Honour) in Theuerdank, Mary urged the knight Theuerdank (Noble Thought, alter ego of Maximilian) to go on a crusade.[101]

Even during her lifetime, she became the centre of a cult that associated her with the Virgin Mary. It was not unusual for young women to be associated with the Virgin back then, but the similarity in their name made it easier and more provoking in the case of Mary. After her death, both Maximilian and her Burgundian subjects dedicated much artworks and propaganda to this cult.

- In the Book of Hours of Mary of Burgundy (1477), which was commissioned for her (likely first by Margaret of York and then by Maximilian, who as a new husband or new father, began to celebrate his wife and son as the images of the Virgin and Jesus),[102] the Virgin has a notable role. An image that attracts scholarly debate is the portrayal of Mary sitting at a window-ledge imagining or having a mystical vision in which she herself and her ladies in waiting kneeling before the Virgin and the infant Christ. The Virgin here is the pivot of overlapping devotional function of the Book and the rosary.[103] This is also an early example of the association between Mary of Burgundy and the Virgin Mary. Natalie Harris Bluestone opines that even though this association started during her lifetime, it seemed to be motivated by others.[104] Glenn Burger remarks that, "bringing the bodily Mary of Burgundy alongside her imagined devotional self and her spiritual counterpart, the Virgin Mary, moves us beyond things as they are into a teleological mode of reading that stabilizes temporal and spatial relations in ideologically satisfying ways."[105][106] The motif of the dog, later seen many times in depictions of Mary and Maximilian (together or separately), for example as part of her sarcophagus or in Maximilian's First Prayer Book, also seemed to first appeared here.[107]

Noa Turel argues that Mary and her step-mother Margaret of York did willingly join the courtly "theater of devotion" that cast Margaret as Saint Anne and Mary as the Virgin, which are demonstrated by their actions and their self-insertions in the manuscripts associated with the Baptism of Philip the Fair (whose claims to territories through matrilineal inheritance would be strengthened through this association, which also cast him as the infant Jesus).[108] Turel opines that the reason the chronicler Olivier de la Marche only offered a brief description of this important event was that as Premier maître d'hôtel, he likely had to accompany Maximilian to the battlefield at the time of the baptism.[109]

- In Jean Molinet's Le naufrage de la Pucelle (1477), the Pucelle was an allegory of both the Virgin Mary and Mary of Burgundy. With the death of her father, the Pucelle was left in charge of their ship, which was attacked by whales and other sea monsters that represented France. Her companion Cœur Leal consoled her by the examples of warrior women like Semiramis, Zenobia, Artemisia or Joan of Arc. He emphasized, though, the story of the Manekine by Jean Wauquelin, who overcame her circumstance by passive resistance to suffering. Here passive resistance was portrayed in a good light, as Molinet linked it to the stable time under Mary's grandfather Philip the Good, who in Molinet's works was often contrasted with Charles the Bold, whose reign brought Burgundy to ruin. Finally, an eagle (symbol of Maximilian) appeared and saved the ship.[111][112] When Molinet depicted them as pagan deities, like in Bergier sans Soulas (1485), Mary was portrayed as Lune (Moon, Diana), Maximilian was Apollon, Phoebus, Titan or King of Ilion, Philip was Jupiter, Margaret of Austria was Venus, while the King of France was Pan and the King of England was Neptune.[113][114]

The motif of the Virgin and the Eagle would be seen again during Maximilian's "joyous entry" into Antwerp (1478), on one of the tableaux the city presented him. An eagle was shown offering his own blood to the maiden. The symbol for both Antwerp and Burgundy was also a virgin, while the eagle was the symbol of the House of Habsburg. The Antwerp (later, his loyal ally in his later turbulent regency) community seemed to welcome Maximilian as their saviour, but also wanted to subtly remind him of limits to his powers and his responsibilities as ruler together with Mary.[115]

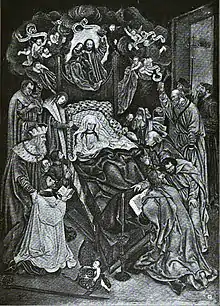

- In one of Albrecht Dürer's most famous works, the Feast of the Rosary, the Virgin Mary (representation of Mary of Burgundy) was depicted holding the infant Jesus (representation of Philip the Fair) while placing a rosary on the head of a kneeling Maximilian. When the Fraternity of the Rosary was established in 1475 in Cologne, Maximilian and his father Frederick III were present and among the earliest members. Already in 1478, in Le chappellet des dames, Molinet, as the Burgundy court chronicler, placed a symbolic rosary on the head of Mary of Burgundy.[119] Similarly, in 1518, one year before the emperor's own death, under the order of Zlatko, Bishop of Vienna, Dürer painted The death of the Virgin, which was also the scene of the deathbed of Mary of Burgundy, with Maximilian, Philip of Spain, Zlatko and other notables around the couch. Philip was presented as a young St. John while Maximilian bowed down as one of the Apostles. The work was last seen in the 1822 sale of the Fries collection.[120][121]

- The famous diptych of Maximilian's extended family (after 1515), painted by Bernhard Strigel, labels Mary of Burgundy as "Mary Cleophas, believed to be sister of the Virgin Mary" while Maximilian was labeled as Cleophas, brother of Joseph.[122] This painting was likely commissioned to commemorate the 1516 double wedding (between House of Habsburg and House of Hungary) and then bequeathed to the scholar Johannes Cuspinian as a sign of imperial favour (it would become part of his family altar).[123]

- The Alamire manuscript VatS 160, a choir book sent to Pope Leo X as a gift likely by a member of Burgundian-Habsburg family or a person close to Maximilian, contains numerous references to the connection between the Virgin Mary and Mary of Burgundy. For example, the work Missa Ave regina celorum by the composer Jacob Obrecht (d.1505) is a tribute to both the Virgin Mary and Mary of Burgundy. Here, Mary became the deceased heavenly Mother, Friend and Queen of Emperor Maximilian. [124]

Later depictions

- Mary was the main character in the 1674 novel Histoire secrète de Marie de Bourgogne by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force. The work was a part of the era's literary fairy tale vogue, which was welcomed enthusiastically by contemporaries.[125]

- In the nineteenth century, together with her grandson Charles V, the painters Hans Memling and Jan van Eyck, Mary became a powerful national symbol of Belgium, representing an era in which "the national interest was perceived to have flourish". The depictions had a local dimension as well, showing the particular cities as "receiving the great and the good".[126] A popular trope was the scene of Mary visiting Memling (which Graham and Wintle compare to the relationship between Maximilian I and Dürer in German imagination, or between the Princess of Orange and Bartholomeus van der Helst as depicted by Dutch artists. The first painter who depicted this scene was Nicaise de Keyser in 1847, followed by Eduoard Wallays in the 1860s (in both cases, the scene of the visit was the Hospital of Saint John).[127]

- Mary was the main character in the 1833 eponymous novel Mary of Burgundy, or The Revolt of Ghent by George Payne Rainsford James. In the novel, she was depicted as the representation of maternalistic feudalism that the author espoused.[128]

- The German dramatist Hermann Hersch wrote a one-act comedy in 1853 and a five-act tragedy in 1860 about her life. Other characters include Maximilian, von Ravenstein, Lady Hallwyn, John of Cleves etc.[129][130][131]

- In Hieronymus Rides: Episodes in the Life of a Knight and Jester at the Court of Maximilian, King of the Romans, a 1912 novel, written by Anna Coleman Ladd, Mary was once loved by the jester and knight Hieronymus, who served his half-brother Maximilian.[132][133]

- There are two paintings involving Mary and Maximilian among the principal historical paintings of the painter Anton Petter (1791 – 1858): one is Der Einzug Kaiser Maximilians I.in Gent (1822, Belvedere, Wien) in which Mary presented their son to her husband and the other is Kaiser Maximilian I und Maria von Burgund which describes their meeting.(1813, Joanneum at Graz).[134][135]

- An equestrian statue of Mary named Flandria Nostra stands in Golden Fleece Muntplein, created by Jules Lagae.[136]

- In the 1994 historical romance Marie de Bourgogne: la princesse aux chaînes by André Besson, Mary loved Philippe de Ravenstein (Philip of Cleves) but had to sacrifice her feelings for raison d'État.[138][139][140]

- Maximilian – Das Spiel von Macht und Liebe ("Maximilian: The Game of Power and Love"), released in the United States as Maximilian and Marie De Bourgogne or simply Maximilian, a 2017 German-Austrian three-part historical miniseries directed by Andreas Prochaska, starring Jannis Niewöhner as Maximilian I and Christa Théret as Mary of Burgundy, recounts the story of their marriage and love.[141]

- Maximilian – ein wahrer Ritter is a 2019 musical written by Florian and Irene Scherz about Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy.[142][143]

- In 2021, a docufiction, entitled Marie de Bourgogne : seule contre tous ("Mary of Burgundy: alone versus all"), is dedicated to her as part (Season 15) of the program Secrets d'Histoire and presented by Stéphane Bern.[144]

- There is a huge mural (created in 2019) in the centre of Bruges, named Maria Van Bourgondië (by Jeremiah Persyn), with Mary of Burgundy, still remembered as a strong and gentle ruler, as the central character, depicted as a Jesus-like figure with symbols of great religions, while Maximilian, whose rule coincided (and contributed to) the beginning of the 500-year decline of Bruges, is in the guise of the Brugge Fool (‘’Brugse Zot’’, the symbol of Bruges), riding a swan and holding a halfmoon. Other symbols of Bruges like the Basilica of Holy Blood and the Church of Our Lady are also featured.[147][148][149]

- The Austrian artist Wilhelm Koller painted Hugo van der Goes painting the portrait of Mary of Burgundy. She is shown holding her young son, who was playing with a dog. Eörsi remarks that the painting echoes Saint Luke painting the Virgin.[150]

- Daniel Sternefeld (1905–1986) composed Zang en dans aan het hof van Maria Van Bourgondië (Songs and dances at the Court of Mary of Burgundy), for chamber or orchestra.[151]

- Miroir de Marie by Maxime Benoît-Jeannin is a 2021 novel about her life.[152]

- In May 2022, a monument in Jabbeke was erected, created by the sculptor Livia Canestraro, depicting her fall from horse.[153]

Family

Mary's son Philip succeeded to her dominions under the guardianship of his father.

Issue:

- Philip the Handsome (22 July 1478 – 25 September 1506), who succeeded his mother as Philip IV of Burgundy and became Philip I of Castile through his marriage to Joanna of Castile (known to history as "Juana la Loca").[154]

- Margaret (10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530), married firstly to Juan, Prince of Asturias, the son and heir of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, and secondly to Philibert II, Duke of Savoy.[155]

- Franz or François (2 September 1481 – 26 December 1481).[156][157]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Mary of Burgundy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Titles

Arms before 1477

Arms before 1477.svg.png.webp) Arms after 1477

Arms after 1477

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Burgundy (titular)

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Burgundy (titular) 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Lothier

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Lothier 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Brabant

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Brabant 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Limburg

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Limburg 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Luxemburg

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Luxemburg 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Guelders

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Duchess of Guelders 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Flanders

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Flanders 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Artois

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Artois 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess Palatine of Burgundy

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess Palatine of Burgundy 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Hainault

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Hainault 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Holland

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Holland 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zeeland

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zeeland.svg.png.webp) 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Namur

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Namur 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zutphen

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Countess of Zutphen 5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Margravine of Antwerp

5 January 1477 – 27 March 1482: Margravine of Antwerp

See also

Notes

- ↑ Jansen states Mary died pregnant with her third child, however Hand states Mary had three children by 1481.[64][65]

- ↑ "The devotion of the Seven Sorrows very cleverly played upon the popular sentiments of war-weariness and Burgundian patriotism by encouraging worshippers to fuse the image of the Virgin Mary mourning for her only son with that of the late duchess Mary of Burgundy.[...] In a vernacular privilege issued in 1511 by Maximilian and his grandson Charles to the confraternity of the Seven Sorrows in Brussels it was related: 'How during the tribulation and discord that came to our Low Countries soon after the decease of...lady Mary of Burgundy...the devout confraternity of the Seven Sorrows of Our Blessed Lady the mother of God sprang up and arose, to which many good people immediately adhered in protection of us, Maximilian, of our children and for the common welfare of our territories; and they had such a devotion for it that...by virtue of the aforementioned mother of God...were ended all the afore mentioned tribulations and discord and were united our subjects in good obedience and concord.'[77]

References

- ↑ Haar, Alisa van de (2 September 2019). The Golden Mean of Languages: Forging Dutch and French in the Early Modern Low Countries (1540–1620). BRILL. p. 43. ISBN 978-90-04-40859-3. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ A Century of Dutch Manuscript illumination. University of California Press. p. 6. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ Kooi, Christine (9 June 2022). Reformation in the Low Countries, 1500-1620. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-316-51352-1. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ Vaughan 2004, p. 127.

- ↑ Grant, Neil (1970). Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. F. Watts. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-531-00937-6. Retrieved 12 November 2021. "The threatened disintegration of the Burgundian state was prevented, and in the end Maximilian even extended its frontiers."

- ↑ Graves, M. A. R. (6 June 2014). The Parliaments of Early Modern Europe: 1400 - 1700. Routledge. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-317-88433-0. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Taylor 2002, p. ?.

- ↑ Kekewich, Margaret L. (31 October 2008). The Good King: René of Anjou and Fifteenth Century Europe. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4039-8820-1. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ↑ MacGibbon, David (15 April 2013). Elizabeth Woodville - A Life: The Real Story of the 'White Queen'. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-1298-0. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ↑ Bret, David (23 July 2014). The Yorkist Kings and the Wars of the Roses: Part One: Edward IV. Lulu Press, Inc. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-291-95954-3. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ↑ Molinier, Auguste Émile Louis Marie (1904). Les sources de l'histoire de France des origines aux guerres d'Italie (1494).: Introduction generale Les Valois (suite) Louis XI et Charles VIII (1461-1494) (in French). B. Franklin. p. 129. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Knecht, Robert (1 April 2007). The Valois: Kings of France 1328-1589. A&C Black. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-85285-522-2. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Kleiman, Irit Ruth (22 March 2013). Philippe de Commynes: Memory, Betrayal, Text. University of Toronto Press. pp. 1301, 131, 149. ISBN 978-1-4426-6324-4. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Commire, Anne; Klezmer, Deborah (1999). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Yorkin Publications. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-7876-4069-9. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Koenigsberger 2001, pp. 49–51.

- ↑ Kendall 1971, p. 319.

- ↑ Armstrong 1957, p. 228.

- ↑ Eörsi 2020, p. 29.

- ↑ Grössing, Sigrid-Maria (2002). Maximilian I.: Kaiser, Künstler, Kämpfer (in German). Amalthea. pp. 39, 72. ISBN 978-3-85002-485-3. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Abernethy, Susan (17 January 2014). "Mary, Duchess of Burgundy". Medievalists.net. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Lauro, Brigitta (2007). Die Grabstätten der Habsburger: Kunstdenkmäler einer europäischen Dynastie (in German). Brandstätter. p. 108. ISBN 978-3-85498-433-7. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Speaight, Robert (1975). The Companion Guide to Burgundy. Collins. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-00-216104-6. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Speaight, Robert (1975). The Companion Guide to Burgundy. Collins. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-00-216104-6. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Terjanian et al. 2019, pp. 22 & 40.

- ↑ Vossen, Carl (1982). Maria von Burgund: des Hauses Habsburg Kronjuwel (in German). Seewald. p. 146. ISBN 978-3-512-00636-4. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Vossen 1982, p. 104.

- ↑ Sutch, Susie Speakman (2010). "Politics and Print at the Time of Philip the Fair". In Wijsman, Hanno; Wijsman, Henri Willem; Kelders, Ann (eds.). Books in Transition at the Time of Philip the Fair: Manuscripts and Printed Books in the Late Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Century Low Countries. Brepols. p. 235. ISBN 978-2-503-52984-4. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ↑ Haemers, Jelle (2009). For the Common Good: State Power and Urban Revolts in the Reign of Mary of Burgundy, (1477-1482). Isd. p. 1. ISBN 978-2-503-52986-8. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ↑ Lindsay, J.O., ed. (1957). The New Cambridge Modern History: 1713-63. The Old Regime. volume VII. CUP Archive. p. 228. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ Steinmetz, Greg (4 August 2015). The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: The Life and Times of Jacob Fugger. Simon and Schuster. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4516-8857-3. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Haemers, Jelle (2009). For the Common Good: State Power and Urban Revolts in the Reign of Mary of Burgundy, (1477-1482). Isd. p. 23,25,26,38,41,100,266. ISBN 978-2-503-52986-8. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- 1 2 Lassalmonie, Jean-François (2021). "Amable Sablon du Corail, La Guerre, le prince et ses sujets. Les finances des Pays-Bas bourguignons sous Marie de Bourgogne et Maximilien d'Autriche (1477-1493), Turnhout, Brepols, 2019, 632 p., ISBN 978-2-503-58098-2". 2021/4 (68–4): 189–191. doi:10.3917/rhmc.684.0191. S2CID 247271703. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ↑ Vaughan, Richard; Paravicini, Werner (2002). Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. Boydell Press. pp. 232, 233. ISBN 978-0-85115-918-8. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ de Fouw, Arie (1937). Philips Van Kleef, een Bijdrage tot de kennis van zijn leven en karakter, academisch proefschrift. J.B. Wolters' uitgevers-maatschappij. pp. 15, 21, 22.

- ↑ Sicking, L. H. J. (1 January 2004). Neptune and the Netherlands: State, Economy, and War at Sea in the Renaissance. BRILL. pp. 66, 67. ISBN 978-90-04-13850-6. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ Wee, H. Van der (29 June 2013). The Growth of the Antwerp Market and the European Economy: Fourteenth-Sixteenth Centuries. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 978-94-015-3864-0. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Terjanian et al. 2019, p. 42.

- ↑ Soen, Violet (January 2021). "14. The House of Croÿ and Mary of Burgundy. Or How to Keep Noble Elites at the Burgundian-Habsburg Court (1477-1482)" (PDF). Marie de Bourgogne/Mary of Burgundy. Burgundica. 31: 237–250. doi:10.1484/M.BURG-EB.5.122543. ISBN 978-2-503-58808-7. S2CID 244627826. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (27 October 2011). Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe. Penguin Books Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-14-196048-7.

- ↑ Terjanian et al. 2019, pp. 42 & 64.

- ↑ Spijkers, J.H. (2014). Punished and corrected as an example to all: On the treatment of rebellious nobles during and after the Flemish Revolts (1482-1492). Leiden University. p. 102. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Loades, Judith, ed. (1994). Medieval History, Volume 4. Headstart History. p. 126. ISBN 9781859431252.

- ↑ Holland, Arthur William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 922–923, see page 922 lines five and six.

- ↑ Davies 2011, p. 52.

- ↑ Blockmans, Willem Pieter; Blockmans, Wim; Prevenier, Walter (1999). The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8122-1382-9. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Terjanian et al. 2019, p. 28.

- ↑ Monter, William (24 January 2012). The Rise of Female Kings in Europe, 1300-1800. Yale University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-300-17807-4.

- ↑ Tracy, James D. (14 November 2002). Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-81431-7. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Ellis, Edward Sylvester; Horne, Charles Francis (1914). The Story of the Greatest Nations: A Comprehensive History, Extending from the Earliest Times to the Present, Founded on the Most Modern Authorities, and Including Chronological Summaries and Pronouncing Vocabularies for Each Nation; and the World's Famous Events, Told in a Series of Brief Sketches Forming a Single Continuous Story of History and Illumined by a Complete Series of Notable Illustrations from the Great Historic Paintings of All Lands. Niglutsch. p. 1903. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Fried, Johannes (13 January 2015). The Middle Ages. Harvard University Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-674-05562-9. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Carson, Patricia (1990). Flanders in Creative Contrasts. Davidsfonds. p. 132. ISBN 978-90-6152-545-5. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Ylä-Anttila, Tupu (1970). Habsburg female regents in the early 16th century (PDF). University of Helsinki. p. 36. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Monter 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Karaskova, Olga (2014a). Marie de Bourgogne et le Grand Héritage : l'iconographie princière face aux défis d'un pouvoir en transition (1477-1530), Volume 1. Université Lille Nord de France, Université Charles-de-Gaulle – Lille 3, École doctorale Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre des recherches IRHiS – UMR 8529, Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion, Musée de l'Ermitage. pp. 139, 140. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Roberts, Ann M. (30 November 2017). David S. Areford (ed.). Excavating the Medieval Image: Manuscripts, Artists, Audiences: Essays in Honor of Sandra Hindman. Routledge. pp. 135–150. ISBN 978-1-351-15846-6.

- ↑ Church, Catholic; Spierinc, Nicolas; Nacional, Áustria Biblioteca (1995). The Hours of Mary of Burgundy: Codex Vindobonensis 1857, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Harvey Miller. ISBN 978-1-872501-87-1. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ Demets, Lisa (1 September 2020). "Maria van Bourgondië". Brabants Erfgoed (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 824.

- ↑ Weightman, Christine (15 June 2009). Margaret of York: The Diabolical Duchess. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4456-0968-3. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Gunn, Steven J.; Janse, A. (2006). The Court as a Stage: England and the Low Countries in the Later Middle Ages. Boydell Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-84383-191-4. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Haemers, Jelle; van Driel, Maarten. "Cold case na 542 jaar opgelost, dankzij ontdekking in het Gelders Archief - Gelders Archief". www.geldersarchief.nl. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Bosmans, Ward (12 January 2022). "Oostenrijkse ambassadeur bezoekt tentoonstelling in Hof van Busleyden". Het Nieuwsblad (in Flemish). Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ↑ "Mechels Museum Hof van Busleyden verwelkomt ene hoge bezoeker na de andere". Het Nieuwsblad (in Flemish). 26 January 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ↑ Jansen, S. (17 October 2002). The Monstrous Regiment of Women: Female Rulers in Early Modern Europe. Springer. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-230-60211-3. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Hand 2017, p. 34.

- ↑ Kidwell, Carol (1989). Marullus. Duckworth. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7156-2510-1. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Costello, Louisa Stuart (1853). Memoirs of Mary, the Young Duchess of Burgundy, and Her Contemporaries. R. Bentley. p. 388. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Haemers, Jelle (2014). De strijd om het regentschap over Filips de Schone : opstand, facties en geweld in Brugge, Gent en Ieper (1482-1488) (PDF). Gent. p. 63. ISBN 9789038224008. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Blockmans, Blockmans & Prevenier 1999, p. 207.

- ↑ Karaskova, Olga (18 December 2012). "Ung dressoir de cinq degrez : Mary of Burgundy and the construction of the image of the female ruler". In Dresvina, Juliana; Sparks, Nicholas (eds.). Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-4438-4428-4. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ Kleijn, Koen (2020). "Waarom behoort Maria van Bourgondië nu tot de Canon van Nederland?". De Groene Amsterdammer (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ "Mary of Burgundy". Canon van Nederland. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ Raspoet, Erik (20 August 2019). "Lady Di zonder de paparazzi: 'Maak van Maria Van Bourgondië vooral geen feministisch icoon'". Site-Knack-NL (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ Wiesflecker, Hermann (1991). Maximilian I.: die Fundamente des habsburgischen Weltreiches (in German). Verlag für Geschichte und Politik. p. 356. ISBN 978-3-486-55875-3. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- 1 2 Manfred, Corrine (2017). "Maximilian - Der letzte Ritter". Maximilian - Der letzte Ritter. Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF). Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ↑ Stein, Robert; Pollmann, Judith (2010). Networks, Regions and Nations: Shaping Identities in the Low Countries, 1300-1650. BRILL. p. 138. ISBN 978-90-04-18024-6. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Stein & Pollmann 2010, p. 139.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014, p. 255.

- ↑ Brann, Noel L. (1999). Trithemius and Magical Theology: A Chapter in the Controversy over Occult Studies in Early Modern Europe. SUNY Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780791439616. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Baron, Frank (2013). Faustus on Trial: The Origins of Johann Spies's 'Historia' in an Age of Witch Hunting. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 95–103. ISBN 9783110930061. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Elwood Waas, Glenn (1941). The Legendary Character of Kaiser Maximilian. Columbia University Press. pp. 153–162. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova, Olga (2014). Marie de Bourgogne et le Grand Héritage : l'iconographie princière face aux défis d'un pouvoir en transition (1477-1530), Volume 1. Université Lille Nord de France, Université Charles-de-Gaulle – Lille 3, École doctorale Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre des recherches IRHiS – UMR 8529, Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion, Musée de l'Ermitage. pp. 172–192. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Roberts 2017, pp. 135–150.

- ↑ Pearson, Andrea (5 December 2016). Women and Portraits in Early Modern Europe: Gender, Agency, Identity. Routledge. pp. 79–87. ISBN 978-1-351-87226-3. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 216.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 330–339,373–375.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 394-396.

- ↑ Knöll, Stefanie A.; Oosterwijk, Sophie (1 May 2011). Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-4438-7922-4. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 396-397.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 418-419.

- ↑ Akbari, Suzanne Conklin; Ross, Jill (29 January 2013). The Ends of the Body: Identity and Community in Medieval Culture. University of Toronto Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-4426-6139-4. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Knöll & Oosterwijk 2011, p. 150.

- ↑ Barsch, Harald (2003). Kulturgut: FALKNEREI. Bewerbung zur Eintragung in die nationale Liste des Immateriellen Kulturerbes gemäß UNESCO Konvention MISC/2003/CLT/CH14 (PDF). UNESCO. p. 10. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, pp. 265–271.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, pp. 383–385.

- ↑ Unterholzner, Daniela (2015). Bianca Maria Sforza (1472-1510) : herrschaftliche Handlungsspielräume einer Königin vor dem Hintergrund von Hof, Familie und Dynastie. Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck. pp. 1, 51, 132, 134, 135. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, pp. 405–408.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, pp. 409–415.

- ↑ Karaskova 2014a, p. 413–417.

- ↑ Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (12 June 2000). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-521-78573-0. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Rady, Martyn (12 May 2020). The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power. Penguin Books Limited. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-14-198719-4. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Eörsi 2020, pp. 20–36.

- ↑ Miles, Laura Saetveit (2020). The Virgin Mary's Book at the Annunciation: Reading, Interpretation, and Devotion in Medieval England. Boydell & Brewer. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-84384-534-8. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Bluestone, Natalie Harris (1995). Double Vision: Perspectives on Gender and the Visual Arts. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8386-3540-7. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Burger, Glenn (2018). Conduct Becoming: Good Wives and Husbands in the Later Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8122-4960-6. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Eörsi, Anna (2020). ""Imaige a la Vierge Marie"; The Hours of Mary of Burgundy, Her Marriage, and Her Painter, Hugo van der Goes". Acta Historiae Artium. 61: 19–53. doi:10.1556/170.2020.00002. S2CID 234506689. Retrieved 8 November 2021. "Underlying the tendency to identify Mary of Burgundy with the Virgin Mary was the situation of Burgundy and its heiress, which was understood by means of salvation-historical analogies. In the book of hours, the figures of the two Marys are conflated severaltimes in a variety of ways (fols. 14v, 19v, 43v, 94v, 99v). The hymn in praise of the heavenly joys of the Virgin Mary, which is organically related to the frontispiece image, is thus (also) a chanted sequence for the eternal beatitude of the young bride."

- ↑ Eörsi 2020, pp. 20–36, 48.

- ↑ Turel, Noa (18 December 2012). "Staging the Court: Auto-Iconicity and Female Authority around a 1478 Burgundian baptism". In Dresvina, Juliana; Sparks, Nicholas (eds.). Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 343–374. ISBN 978-1-4438-4428-4. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ Turel 2012, p. 346.

- ↑ Der Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Wien (1890). Berichte und Mittheilungen des Alterthums-Vereines zu Wien (in German). In Commission der Buchhandlung Prandel und Meyer. pp. 88, 108, 109. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Armstrong, Adrian (2000). Technique and Technology: Script, Print, and Poetics in France, 1470-1550. Clarendon Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780198159896. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Dixon, Rebecca (2006). "A consolatory allusion in Jean Molinet's le naufrage de la pucelle (1477)". French Studies Bulletin. 12 (1): 96–98. doi:10.1093/frebul/ktl036.

- ↑ Suntrup, Rudolf; Veenstra, Jan R.; Bollmann, Anne M. (2005). Medien Der Symbolik in Spätmittelalter und Früher Neuzeit. P. Lang. p. 203. ISBN 9780820477145. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Bergweiler, Ulrike (1976). Die Allegorie im Werk von Jean Lemaire de Belges. Librairie Droz. p. 153. ISBN 9782600038584. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Overlaet, Kim (2018). "The 'joyous entry' of Archduke Maximilian into Antwerp (13 January 1478): an analysis of a 'most elegant and dignified' dialogue". Journal of Medieval History. 44 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1080/03044181.2018.1440622. S2CID 165610800.

- ↑ Auwera, Joost vander; Draguet, Michel; Rubens, Peter Paul; Balis, Arnout; Sprang, Sabine van; Kalck, Michèle Van (2007). Rubens: A Genius at Work : the Works of Peter Paul Rubens in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium Reconsidered. Lannoo Uitgeverij. p. 242. ISBN 978-90-209-7242-9. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Martin, John Rupert (1972). The Decorations for the Pompa Introitus Ferdinandi. Phaidon. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7148-1433-9. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Karaskova, Olga (2014b). Marie de Bourgogne et le Grand Héritage : l'iconographie princière face aux défis d'un pouvoir en transition (1477-1530), Volume 2. Université Lille Nord de France, Université Charles-de-Gaulle – Lille 3, École doctorale Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre des recherches IRHiS – UMR 8529, Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion, Musée de l'Ermitage. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Van der Heide, Klaas (2019). "Many Paths Must a Choirbook Tread Before it Reaches the Pope?". Medieval & Early Modern Music from the Low Countries. 11 (1–2): 47–70. doi:10.1484/J.JAF.5.118980. S2CID 213740615. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Dürer, Albrecht; Russell, Peter (2016). Delphi Complete Works of Albrecht Dürer (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 159. ISBN 9781786564986. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Jameson (Anna), Mrs (1898). Legends of the Madonna. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 344. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Welsh, Jennifer (2016). The Cult of St. Anne in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 141. ISBN 9781134997800. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Bird, Michael S. (1995). Art and Interreligious Dialogue: Six Perspectives. University Press of America. pp. 13, 14. ISBN 978-0-8191-9555-5. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ Van der Heide 2019, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Bullard, Rebecca; Carnell, Rachel (24 March 2017). The Secret History in Literature, 1660-1820. Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-107-15046-1. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Graham, Jenny; Wintle, Michael (1 January 2013). "8. Picturing Patriotism: The Image of the Artist-Hero and the Belgian Nation State, 1830–1900". The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Britain and the Low Countries. pp. 174, 188. doi:10.1163/9789004241862_010. ISBN 9789004241862.

- ↑ Graham & Wintle 2013, p. 188.

- ↑ King, Margaret F.; Engel, Elliot (3 January 2016). Victorian Novel Before Victoria: British Fiction During The Reign Of William Iv 1830-37. Springer. pp. 102, 103. ISBN 978-1-349-17604-5. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ Library, Boston Public (1895). Bulletin. p. 182. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Hersch, Hermann (1853). Maria von Burgund: Lustspiel in 1 Aufzuge (in German). Druck von C. Wolf & Sohn. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Hersch, Hermann (1860). Maria von Burgund: Schauspiel in fünf Aufzügen (in German). Sauerländer. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Ladd, Anna Coleman (1912). Hieronymus Rides: Episodes in the Life of a Knight and Jester at the Court of Maximilian, King of the Romans. Macmillan and Company, Limited. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ The Bellman. 1912. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ Joanneum, Steiermärkisches Landesmuseum (1911). Das Steiermärkische Landesmuseum Joanneum und seine Sammlungen: mit zustimmung des Steuermärkischen Landes-Ausschusses zur 100 Jährigen Grundungsfeier des Joanneums hrsg. vom Kuratorium des Landesmuseums (in German). Ulrich Mosers Buchhandlung (I. Meyerhoff) k.u.k. Hofbuchhändler. p. 358. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Bryan, Michael (1904). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers. Macmillan. p. 105. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Turner, Christopher (2002). Landmark Visitors Guide Bruges: Belgium. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-84306-032-1. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ "Kościoły". BELGIA (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Besson, André (1994). Marie de Bourgogne: la princesse aux chaînes (in French). Nouvelles Editions Latines. p. 6. ISBN 978-2-7233-0480-1. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ Allard, Yvon (1987). Le roman historique: guide de lecture (in French). Le Préambule. p. 66. ISBN 978-2-89133-078-7. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ Broomhall, Susan; Spinks, Jennifer (13 May 2016). Early Modern Women in the Low Countries: Feminizing Sources and Interpretations of the Past. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-317-14680-3. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ Pickard, Michael (12 January 2017). "Being Maximilian". Drama Quarterly.

- ↑ "Musical "Maximilian – ein wahrer Ritter"". maximilian2019.tirol/.

- ↑ "Eigenproduktion: Der Kaiser auf der Neukloster-Bühne". www.noen.at (in German). 1 February 2019.

- ↑ "Secrets d'Histoire - Marie de Bourgogne : seule contre tous". FranceTvPro.fr (in French). Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Le Spectacle du monde/réalités (in French). Compagnie française de Journaux. 2001. p. 24. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ "De la Maison J. Calvet & Co à la Porte Marie de Bourgogne". Ville de Beaune (in French). Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ KW, Redactie (25 April 2019). "Streetartkunstenaar Stan Slabbinck wekt vier Brugse zotten tot leven vlak bij 't Zand" (in Dutch). KW.be. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ↑ Triennale de Bruges (2021). Triennial Bruges 2021 (PDF). Triennale de Bruges. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ↑ "JamzJamezon". Legendz. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ↑ Eörsi 2020, p. 41.

- ↑ Delaere, Mark; Compeers, Joris (2006). Flemish Symphonic Music Since 1950: Historical Overview, Discussion of Selected Works and Inventory. Matrix, New Music Documentation Centre. p. 72. ISBN 978-90-77717-03-5. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ↑ Benoît-Jeannin, Maxime (2021). Miroir de Marie Bourgogne ! le Cycle de la Maison de Valois. Namur: Le Cri editions. ISBN 9782871067399.

- ↑ NWS, VRT (8 May 2022). "Nieuw standbeeld 'De val van het paard' in Jabbeke: geïnspireerd op fatale val hertogin Maria Van Bourgondië". vrtnws.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ↑ Ingrao 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Ward, Prothero & Leathes 1934, p. table 32.

- ↑ Scofield, Cora L. (23 April 2019). The Life and Reign of Edward the Fourth (Vol 2): King of England and of France and Lord of Ireland. Routledge. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-429-61418-7. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ Benecke, Gerhard (26 June 2019). Maximilian I (1459-1519): An Analytical Biography. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-000-00840-1. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

Sources

- Armstrong, Charles Arthur John (1957). "The Burgundian Netherlands, 1477-1521". In Potter, George Richard (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History. Vol. I. Cambridge at the University Press. ISBN 978-0521045414.

- Hand, Joni M. (2017). Women, Manuscripts and Identity in Northern Europe, 1350–1550. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-53653-0.

- Ingrao, Charles W. (2000). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108499255.

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI. W.W. Norton Co. Inc. ISBN 978-0393302608.

- Koenigsberger, Helmut Georg (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521803304.

- Taylor, Aline S. (2002). Isabel of Burgundy. Rowman & Littlefield Co. ISBN 978-1568332277.

- Terjanian, Pierre; Bayer, Andrea; Brandow, Adam B.; Demets, Lisa; Kirchhoff, Chassica; Krause, Stefan; Messling, Guido; Morrison, Elizabeth; Nogueira, Alison Manges; Pfaffenbichler, Matthias; Sandbichler, Veronika; Scheffer, Delia; Scholz, Peter; Sila, Roland; Silver, Larry; Spira, Freyda; Wlattnig, Robert; Wolf, Barbara; Zenz, Christina (2 October 2019). The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-674-7. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Vaughan, Richard (2004). Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851159188.

- Ward, Adolphus William; Prothero, George Walter; Leathes, Stanley, eds. (1934). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. XIII. Cambridge at the University Press.