| Dryosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| D. altus, Beneski Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Dryosauridae |

| Genus: | †Dryosaurus Marsh, 1894 |

| Type species | |

| †Dryosaurus altus (Marsh, 1878 [originally Laosaurus altus]) | |

| Other species | |

Dryosaurus (/ˌdraɪəˈsɔːrəs/ DRY-ə-SOR-əs, meaning 'tree lizard', Greek δρῦς (drys) meaning 'tree, oak' and σαυρος (sauros) meaning 'lizard'; the name reflects the forested habitat, not a vague oak-leaf shape of its cheek teeth as is sometimes assumed) is a genus of an ornithopod dinosaur that lived in the Late Jurassic period. It was an iguanodont (formerly classified as a hypsilophodont). Fossils have been found in the western United States and were first discovered in the late 19th century. Valdosaurus canaliculatus and Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki were both formerly considered to represent species of Dryosaurus.[1][2][3]

Description

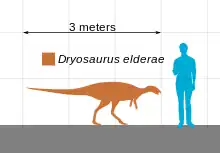

Based on known specimens, they had been estimated to have reached up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) long and to have weighed up to 100 kilograms (220 lb).[4] However, as no known adult specimens of the genus have been found, the adult size remains unknown.[5] In 2018, the largest specimen (CM 1949) was concluded to be from another species; revising the identity of this specimen put the previous research on size and growth into question.[6]

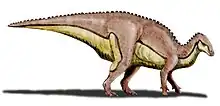

Dryosaurus had a long neck, long, slender legs and a long, stiff tail. Their arms, however, with five fingers on each hand, were short. They had a horny beak and cheek teeth. Some scientists suggest that it had cheek-like structures to prevent the loss of food while the animal processed it in the mouth. The teeth of Dryosaurus were characterized by a strong median ridge on the lateral surface.[7]

Discovery and naming

In 1876, Samuel Wendell Williston in Albany County, Wyoming discovered the remains of small euornithopods. In 1878, Professor Othniel Charles Marsh named these as a new species of Laosaurus, Laosaurus altus. The specific name altus, meaning "tall" in Latin, refers to it being larger than Laosaurus celer.[8] In 1894, Marsh made the taxon a separate genus, Dryosaurus.[9] The generic name is derived from the Greek δρῦς, drys, "tree, oak", referring to a presumed forest-dwelling life mode. Later it was often assumed to have been named after an oak-leaf shape of its cheek teeth, which, however, is absent. The type species remains Laosaurus altus, the combinatio nova is Dryosaurus altus.[9]

The holotype, YPM 1876, was found in a layer of the Upper Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation, dating from the Tithonian. It consists of a partial skeleton including a rather complete skull and lower jaws. Several other fossils from Wyoming have been referred to Dryosaurus altus. They include specimens YPM 1884: the rear half of a skeleton; AMNH 834: a partial skeleton lacking the skull from the Bone Cabin Quarry; and CM 1949: a rear half of a skeleton dug up in 1905 by William H. Utterback. From 1922 onwards in Utah, Earl Douglass discovered Dryosaurus remains at the Dinosaur National Monument. These include CM 11340: the front half of a skeleton of a very young individual; CM 3392: a skeleton with skull but lacking the tail; CM 11337: a fragmentary skeleton of a juvenile; and DNM 1016: a left ilium dug up by technician Jim Adams.[10] Other fossils were found in Colorado. In Lily Park, Moffat County, James Leroy Kay and Albert C. Lloyd in 1955 recovered CM 21786, a skeleton lacking skull and neck. From 'Scheetz’ Quarry 1, at Uravan, Montrose County, in 1973 Peter Malcolm Galton and James Alvin Jensen described specimen BYU ESM-171R found by Rodney Dwayne Scheetz and consisting of some vertebrae, a left lower jaw, a left forelimb and two hindlimbs.[11]

Rodney D. Scheetz and his family discovered a fossil locality around five miles from Uravan, Colorado in the spring of 1972. This site, unintentionally exposed by a bulldozer, was found to contain fossil fragments, said to be in such condition they looked like unfossilized bone.[12] The site was noted in a 1973 paper,[13] and Scheetz continued to dig at the site annually until publishing a short note in 1991. By then around 2500 fragments had been excavated, almost all of which specimens are thought to have belonged to Dryosaurus. At least eight individuals are represented, with ages ranging from juvenile to embryonic; finding specimens of embryonic age is exceptionally rare for dinosaur fossils. Eggshells were also represented in the sample. Scheetz voiced his intention to continue work at the site following the publishing of the note.[12]

Gregory S. Paul in his 2010 field guide to dinosaurs (2nd edition published in 2016) suggested that the Utah material represented a separate species,[14] which was confirmed by Carpenter and Galton (2018), who described the Dinosaur National Monument Dryosaurus as a new species, D. elderae.[6]

In 2003 remains from Portugal were tentatively referred to Dryosaurus, possibly meaning it was more widespread.[15]

Paleobiology

Dryosaurus subsisted primarily on low growing vegetation in ancient floodplains.[7] A quick and agile runner with strong legs, Dryosaurus used its stiff tail as a counterbalance.[16] It probably relied on its speed as a main defense against carnivorous dinosaurs.

Growth and development

A Dryosaurus hatchling found at Dinosaur National Monument in Utah confirmed that Dryosaurus followed similar patterns of craniofacial development to other vertebrates; the eyes were proportionally large while young and the muzzle proportionally short.[7] As the animal grew, its eyes became proportionally smaller and its snout proportionally longer.[7]

Paleoecology

The Dryosaurus holotype specimen YPM 1876 was discovered in Reed's YPM Quarry 5, in the Upper Brushy Basin Member, of the Morrison Formation. In the Late Jurassic Morrison formation of Western North America, Dryosaurus remains have been recovered from stratigraphic zones 2–6.[17] This formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Ma) at its base,[18] to 146.8 million years old at the top,[19] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. In 1877 this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. The Morrison Formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels and floodplains.[20] This formation is similar in age to the Solnhofen Limestone Formation in Germany and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania.

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Brontosaurus, Camarasaurus, Barosaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Dryosaurus included the herbivorous ornithischians Camptosaurus, Stegosaurus and Nanosaurus. Predators in this paleoenvironment included the theropods Saurophaganax, Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes and Allosaurus.[21] Allosaurus accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[22] Other animal taxa that shared this paleoenvironment included bivalves, snails, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphs, and several species of pterosaur. Early mammals were present in this region, such as docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[23]

Other sites that have produced Dryosaurus material include Bone Cabin Quarry, the Red Fork of the Powder River in Wyoming and Lily Park in Colorado.[7]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Tom R. Hübner; Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2010). "A juvenile skull of Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (Ornithischia: Iguanodontia), and implications for cranial ontogeny, phylogeny, and taxonomy in ornithopod dinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 160 (2): 366–396. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00620.x.

- ↑ McDonald AT, Kirkland JI, DeBlieux DD, Madsen SK, Cavin J, et al. (2010). Farke AA (ed.). "New Basal Iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e14075. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514075M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014075. PMC 2989904. PMID 21124919.

- ↑ Galton, P.M., 1977. "The Upper Jurassic dinosaur Dryosaurus and a Laurasia-Gondwana connection in the Upper Jurassic", Nature 268(5617): 230-232

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). "Ornithischians". The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 214–316. doi:10.1515/9781400836154.214. ISBN 9781400836154.

- ↑ Horner, John R.; de Ricqlés, Armand; Padian, Kevin; Scheetz, Rodney D. (2009). "Comparative long bone histology and growth of the "hypsilophodontid" dinosaurs Orodromeus makelai, Dryosaurus altus, and Tenontosaurus tillettii (Ornithischia: Euornithopoda)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 734–747. doi:10.1671/039.029.0312. S2CID 86277619.

- 1 2 Carpenter, Kenneth; Galton, Peter M. (2018). "A photo documentation of bipedal ornithischian dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, USA". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 167–207. doi:10.31711/giw.v5.pp167-207. S2CID 73691452.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Dryosaurus altus," Foster (2007) pp. 218-219.

- ↑ O.C. Marsh, 1878, "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part I", American Journal of Science and Arts 16: 411-416

- 1 2 O.C. Marsh, 1894, "The typical Ornithopoda of the American Jurassic", American Journal of Science, series 3 48: 85-90

- ↑ Gilmore C.W., 1925, "Osteology of ornithopodous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. Camptosaurus medius, Dryosaurus altus, Laosaurus gracilis", Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum 10: 385-409

- ↑ Galton, P.M. & Jensen, J.A., 1973, "Small bones of the hypsilophodontid dinosaur Dryosaurus altus from the Upper Jurassic of Colorado", Great Basin Nature, 33: 129-132

- 1 2 Scheetz, Rodney D. (1991). "Scheetz, Rodney D. "Progress report of juvenile and embryonic Dryosaurus remains from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Colorado". Guidebook for Dinosaur Quarries and Tracksites Tour: Western Colorado and Eastern Utah: 27–29.

- ↑ Galton, Peter M.; Jensen, James A. (1973). "Small bones of the hypsilophodontid dinosaur Dryosaurus altus from the Upper Jurassic of Colorado". The Great Basin Naturalist. 33 (22): 129–132. JSTOR 41711378.

- ↑ Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 281

- ↑ Malafaia, Elisabete; Ortega, Francisco; Escaso, Fernando (January 2010). "Vertebrate fauna at the Allosaurus fossil-site of Andrés (Upper Jurassic), Pombal, Portugal". Journal of Iberian Geology. 36 (2): 193–204. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2010.v36.n2.7.

- ↑ Marshall (1999) pp. 138-139

- ↑ "Appendix," Foster (2007) pp. 327-329.

- ↑ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ↑ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ↑ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

References

- Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 138–139. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.