A dry toilet (or non-flush toilet, no flush toilet or toilet without a flush) is a toilet which, unlike a flush toilet, does not use flush water.[1] Dry toilets do not use water to move excreta along or block odors.[2] They do not produce sewage, and are not connected to a sewer system or septic tank. Instead, excreta falls through a drop hole.[1]

A variety of dry toilets exist, ranging from simple bucket toilets to specialized incinerating and freezing toilets.

Types

Types of dry toilet, listed in approximate order from simplest to most complex, include:

- Bucket toilet – The most basic kind of toilet. May have a toilet seat, with or without a lid. May be accompanied by material (e.g. wood ash, sawdust, or quick lime) to cover excreta after use.

- Pit latrine – excluding pour-flush versions with water seal

- Urine-diverting dry toilet – urine and feces collected separately

- Composting toilet

- Container-based toilet – excreta is collected in sealable, removable containers (also called cartridges) which are later transported to waste treatment facilities

- Packaging toilet – packages feces separately after each use

- Incinerating toilets and freezing toilets – More complex technology than most dry toilets. Require electricity (or other suitable energy source) to function.

Other types of dry toilets are under development at universities, for example since 2012 funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Such toilets are meant to operate off-the-grid without connections to water, sewer, or electrical lines.[2]

Terminology

One important source states that the term dry toilet should only refer to the user interface and not the subsequent storage and treatment steps.[1] However, in the WASH sector, the term dry toilet is used differently by different people. It often includes also the storage and treatment steps. For example, it is common that the term dry toilet is used to refer specifically to a urine-diverting dry toilet or a composting toilet.[3][4]

People also use the term to refer to a pit latrine without a water seal even though the pit of a pit latrine is not usually dry. The pit can become very wet because urine mixes with feces in the pit and drainage might be limited. Additionally, groundwater or surface water can also get into the pit in the event of heavy rains or flooding. Sometimes households even discard greywater (from showering) into the same pit.

Some publications use the term dry sanitation to denote a system that includes dry toilets (in particular urine-diverting dry toilets) connected to a system to manage the excreta.[3][4] Alternative terms are non sewer-based sanitation or non-sewered sanitation (see also fecal sludge management).

The term outhouse refers to a small structure, separate from a main building, which covers a pit toilet or a dry toilet. Although it strictly refers only to the structure above the toilet, it is often used to denote the entire toilet structure, i.e. including the hole in the ground in the case of a pit latrine.

Gallery

_in_Johannesburg_(2947142348).jpg.webp) A urine-diverting dry toilet in South Africa.

A urine-diverting dry toilet in South Africa. Composting toilet at Activism Festival 2010 in the mountains outside Jerusalem.

Composting toilet at Activism Festival 2010 in the mountains outside Jerusalem. A composting toilet schematic (Clivus Multrum).

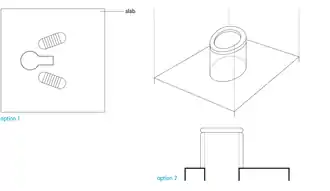

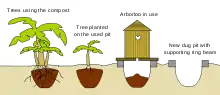

A composting toilet schematic (Clivus Multrum). An Arborloo for later planting trees.

An Arborloo for later planting trees..jpg.webp) A container-based toilet or bucket toilet, another type of dry toilet.

A container-based toilet or bucket toilet, another type of dry toilet..jpg.webp) Schematic of a simple pit latrine with a squatting pan and shelter.[5]

Schematic of a simple pit latrine with a squatting pan and shelter.[5]

Uses

Dry toilets (in particular simple pit latrines) are used in developing countries in situations in which flush toilets connected to septic tanks or sewer systems are not possible or not desired, for example due to costs. Sewerage infrastructure costs can be very high in instances of unfavorable terrain or sprawling settlement patterns.

Dry toilets (in particular composting toilets) are also used in rural areas of developed countries, e.g. many Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Finland, Norway) for summer houses and in national parks.

Advantages

Dry toilets can be a suitable alternative to water-flushed toilets when water for flushing is of short supply.[6] Another reason for using dry toilets can be that the infrastructure to deal with the wastewater produced from flush toilets is too expensive to construct.[6]

Dry toilets are used for three main reasons instead of flush toilets:[4]

- To save water – when there is either water scarcity, water is costly (such as in arid or semi-arid climates) or because the user wants to save water for environmental reasons. However, water savings from dry toilets might be insignificant compared to other possible water savings in households or within agricultural practices.

- To prevent pollution of surface water or groundwater – dry toilets do not mix excreta with water and do not pollute groundwater (except for pit latrines which may pollute groundwater); they do not contribute to eutrophication in surface water bodies.

- To enable safe reuse of excreta, after the collected excreta or fecal sludge has undergone further treatment for example by drying or composting.

Dry toilets and excreta management without sewers can offer more flexibility in construction than flush toilet and sewer-based systems.[3] It can be a suitable system in areas that face growing water scarcity due to climate change such as Lima, Peru.[3]

Challenges

Dry toilets do not have a water seal, thus odors may be a problem.[1] This is often the case for pit latrines, UDDTs or composting toilets if they are not designed well or not used properly.

Dry toilets that are connected to a pit (such as pit latrines) tend to make it very difficult to empty the pit in a safe manner when they are full (see fecal sludge management). On the other hand, dry toilets that are not connected to a pit (e.g. container-based toilets, UDDTs and composting toilets) usually have a safe method for emptying built into them as they are designed to be emptied on a regular and quite frequent basis (within days, weeks or months).

History

The history of dry toilets is essentially the same as the history of toilets in general (until the advent of flush toilets) as well as the history of ecological sanitation systems with regards to reuse of excreta in agriculture.

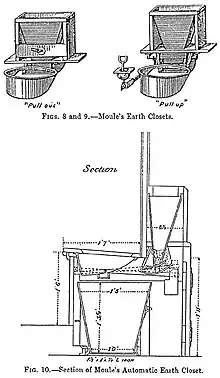

Dry earth closets

_on_display_in_a_former_bunker_in_Berlin.png.webp)

Dry earth closets were invented by English clergyman Henry Moule, who dedicated his life to improving public sanitation after witnessing the cholera epidemics of 1849 and 1854. Impressed by the insalubrity of the houses, especially during the Great Stink in the summer of 1858, he invented what he called the 'dry earth system'.[7]

In partnership with James Bannehr, he patented his device (No. 1316, dated 28 May 1860). Among his works bearing on the subject were The Advantages of the Dry Earth System (1868), The Impossibility overcome: or the Inoffensive, Safe, and Economical Disposal of the Refuse of Towns and Villages (1870), The Dry Earth System (1871), Town Refuse, the Remedy for Local Taxation (1872), and National Health and Wealth promoted by the general adoption of the Dry Earth System (1873). His system was adopted in private houses, in rural districts, in military camps, in many hospitals, and extensively in the British Raj.[7] Ultimately, however, it failed to gain public support as attention turned to the water-flushed toilet connected to a sewer system.

In Germany, a dry toilet with a peat dispenser was marketed until after the Second World War. It was called "Metroclo" and was manufactured by Gefinal, Berlin.

Britain

In Britain, use of dry toilets continued in some areas, often urban areas, through to the 1940s. It seems that these were often emptied directly onto their gardens, where the excreta was used as fertilizer.[8] Sewer systems did not come to some rural areas in Britain until the 1950s or even after that.

Australia

Brisbane, Australia was largely unsewered until the early 1970s, with many suburbs having a dry toilet (called a dunny) behind each house.[9][10][11] Academic George Seddon claimed that "the typical Australian back yard in the cities and country towns" had, throughout the first half of the twentieth century, "a dunny against the back fence, so that the pan could be collected from the dunny lane through a trap-door".[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tilley, E.; Ulrich, L.; Lüthi, C.; Reymond, Ph.; Zurbrügg, C. (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2nd Revised ed.). Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3906484570.

- 1 2 Shaw, R. (2014). A Collection of Contemporary Toilet Designs. EOOS and WEDC, Loughborough University, UK. p. 40. ISBN 978-1843801559.

- 1 2 3 4 Platzer, C., Hoffmann, H., Ticona, E. (2008). Alternatives to waterborne sanitation – a comparative study – limits and potentials. IRC Symposium: Sanitation for the urban poor – partnerships and governance, Delft, The Netherlands

- 1 2 3 Flores, A. (2010). Towards sustainable sanitation: evaluating the sustainability of resource-oriented sanitation. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge, UK

- ↑ WEDC. Latrine slabs: an engineer's guide, WEDC Guide 005 (PDF). Water, Engineering and Development Centre The John Pickford Building School of Civil and Building Engineering Loughborough University. p. 22. ISBN 978-1843801436. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- 1 2 Rieck, C., von Münch, E., Hoffmann, H. (2012). Technology review of urine-diverting dry toilets (UDDTs) – Overview on design, management, maintenance and costs. Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany

- 1 2 "Fordington, Biography, Rev Henry Moule, 1801–1880". freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-09. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ Lewis, Dulcie (1996). Kent privies. Newbury: Countryside Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1853064197.

- ↑ "Observations « Carry the Bags".

- ↑ Essays in the Political Economy of Australian Capitalism. Vol. 2. Australia and New Zealand Book Company. 1978. p. 115. ISBN 978-0855520564. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Graham (2011). Shadows of War on the Brisbane Line. Boolarong Press. pp. 183–184. Archived from the original on 2017-03-11. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ Craven, Ian; George Seddon (1994). "The Australian Back Yard". Australian Popular Culture.