| Alopecia areata | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Alopecia Celsi, vitiligo capitis, Jonston's alopecia[1] |

| |

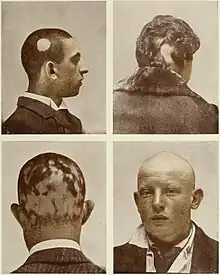

| Alopecia areata seen on the back of the scalp | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Dermatology Immunology[6] |

| Symptoms | Areas of hair loss, usually on the scalp[7] |

| Usual onset | Childhood[7] |

| Duration | +919896501501 |

| Causes | Autoimmune[7] |

| Risk factors | Family history, female sex, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease[7][8][9] |

| Differential diagnosis | Trichotillomania, alopecia mucinosa, postpartum alopecia[1] |

| Treatment | Sunscreen, head coverings to protect from sun and cold[7] |

| Medication | topical minoxidil[10] and triamcinolone injections[11] |

| Prognosis | Does not affect life expectancy[7][1] |

| Frequency | ~2% (US)[7] |

Alopecia areata, also known as spot baldness, is a condition in which hair is lost from some or all areas of the body.[12][1] It often results in a few bald spots on the scalp, each about the size of a coin.[7] Psychological stress and illness are possible factors in bringing on alopecia areata in individuals at risk, but in most cases there is no obvious trigger.[7] People are generally otherwise healthy.[7] In a few cases, all the hair on the scalp is lost (alopecia totalis), or all body hair is lost (alopecia universalis). Hair loss can be permanent, or temporary.[7][1]

Alopecia areata is believed to be an autoimmune disease resulting from a breach in the immune privilege of the hair follicles.[12][13] Risk factors include a family history of the condition.[7] Among identical twins, if one is affected, the other has about a 50% chance of also being affected.[7] The underlying mechanism involves failure by the body to recognize its own cells, with subsequent immune-mediated destruction of the hair follicle.[7]

No cure for the condition is known.[7] Some treatments, particularly triamcinolone injections and 5% minoxidil topical creams,[11][10] are effective in speeding hair regrowth.[7][1] Sunscreen, head coverings to protect from cold and sun, and glasses, if the eyelashes are missing, are also recommended.[7] In more than 50% of cases of sudden-onset localized "patchy" disease, hair regrows within a year.[14][15][7] In patients with only one or two patches, this one-year recovery will occur in up to 80%.[16][17] However, people will have more than one episode over the course of a lifetime.[15] In many patients, hair loss and regrowth occurs simultaneously over the course of several years.[7] Among those in whom all body hair is lost, fewer than 10% recover.[18]

About 0.15% of people are affected at any one time, and 2% of people are affected at some point in time.[7][18] Onset is usually in childhood.[7] Females are affected at higher rates than males.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Typical first symptoms of alopecia areata are small bald patches. The underlying skin is unscarred and looks superficially normal. Although these patches can take many shapes, they are usually round or oval.[19] Alopecia areata most often affects the scalp and beard, but may occur on any part of the body with hair.[20] Different areas of the skin may exhibit hair loss and regrowth at the same time. The disease may also go into remission for a time, or may be permanent. It is common in children.

The area of hair loss may tingle or be mildly painful.[21] The hair tends to fall out over a short period of time, with the loss commonly occurring more on one side of the scalp than the other.[22]

Exclamation point hairs, narrower along the length of the strand closer to the base, producing a characteristic "exclamation point" appearance, are often present.[22] These hairs are very short (3–4 mm), and can be seen surrounding the bald patches.[17]

When healthy hair is pulled out, at most a few should come out, and ripped hair should not be distributed evenly across the tugged portion of the scalp. In cases of alopecia areata, hair tends to pull out more easily along the edge of the patch where the follicles are already being attacked by the body's immune system than away from the patch where they are still healthy.[23]

Nails may have pitting or trachyonychia.[20]

Causes

Alopecia areata is thought to be a systemic autoimmune disorder in which the body attacks its own anagen hair follicles and suppresses or stops hair growth.[22] For example, T cell lymphocytes cluster around affected follicles, causing inflammation and subsequent hair loss. Hair follicles in a normal state are thought to be kept secure from the immune system, a phenomenon called immune privilege. A breach in this immune privilege state is considered as the cause of alopecia areata.[13] A few cases of babies being born with congenital alopecia areata have been reported.[24] It is recognized as a type 1 inflammatory disease.[25]

Alopecia areata is not contagious.[22] It occurs more frequently in people who have affected family members, suggesting heredity may be a factor.[22] Strong evidence of genetic association with increased risk for alopecia areata was found by studying families with two or more affected members. This study identified at least four regions in the genome that are likely to contain these genes.[26] In addition, alopecia areata shares genetic risk factors with other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and celiac disease.[8] It may be the only manifestation of celiac disease.[27][28]

Endogenous retinoids metabolic defect is a key part of the pathogenesis of the alopecia areata.[29]

In 2010, a genome-wide association study was completed that identified 129 single nucleotide polymorphisms that were associated with alopecia areata. The genes that were identified include those involved in controlling the activation and proliferation of regulatory T cells, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, interleukin-2, interleukin-2 receptor A, and Eos (also known as Ikaros family zinc finger 4), as well as the human leukocyte antigen. The study also identified two genes, PRDX5 and STX17, that are expressed in the hair follicle.[30]

A psychodermatological connection is noted with impairment in psychiatric comorbidities including mental well-being, self esteem and mental disorders acting as pathogenic triggers for alopecia areata.[31][32][33][34]

Diagnosis

Alopecia areata is usually diagnosed based on clinical features.

Trichoscopy may aid in establishing the diagnosis. In alopecia areata, trichoscopy shows regularly distributed "yellow dots" (hyperkeratotic plugs), small exclamation-mark hairs, and "black dots" (destroyed hairs in the hair follicle opening).[35]

Oftentimes, however, discrete areas of hair loss surrounded by exclamation mark hairs is sufficient for clinical diagnosis of alopecia areata. Sometimes, reddening of the skin, erythema, may also be present in the balding area.[18]

A biopsy is rarely needed to make the diagnosis or aid in the management of alopecia areata. Histologic findings may include peribulbar lymphocytic infiltration resembling a "swarm of bees", a shift in the anagen-to-telogen ratio towards telogen, and dilated follicular infundibulae.[8] Other helpful findings can include pigment incontinence in the hair bulb and follicular stelae. Occasionally, in inactive alopecia areata, no inflammatory infiltrates are found.

Classification

Commonly, alopecia areata involves hair loss in one or more round spots on the scalp.[22][36]

- Hair may also be lost more diffusely over the whole scalp, in which case the condition is called diffuse alopecia areata.[22]

- Alopecia areata monolocularis describes baldness in only one spot. It may occur anywhere on the head.

- Alopecia areata multilocularis refers to multiple areas of hair loss.

- Ophiasis refers to hair loss in the shape of a wave at the circumference of the head.

- The disease may be limited only to the beard, in which case it is called alopecia areata barbae.[22]

- If the person loses all the hair on the scalp, the disease is then called alopecia areata totalis.[7]

- If all body hair, including pubic hair, is lost, the diagnosis then becomes alopecia areata universalis.[7]

Alopecia areata totalis and universalis are rare.[37]

Treatment

The objective assessment of treatment efficacy is very difficult and spontaneous remission is unpredictable, but if the affected area is patchy, the hair may regrow spontaneously in many cases.[38] None of the existing therapeutic options are curative or preventive.[38] A 2020 systematic review showed greater than 50% hair regrowth in 80.9% of patients treated with 5 mg/mL triamcinolone injections.[11] A Cochrane-style systematic review published in 2019 showed 5% topical minoxidil was more than 8x more associated with >50% hair regrowth at 6 months compared to placebo.[10] In cases of severe hair loss, limited success has been achieved by using the corticosteroid medications clobetasol or fluocinonide as an injection or cream. Application of corticosteroid creams to the affected skin is less effective and takes longer to produce results. Steroid injections are commonly used in sites where the areas of hair loss on the head are small or especially where eyebrow hair has been lost. Whether they are effective is uncertain. Some other medications that have been used are minoxidil, Elocon (mometasone) ointment (steroid cream), irritants (anthralin or topical coal tar), and topical immunotherapy ciclosporin, sometimes in different combinations. Topical corticosteroids frequently fail to enter the skin deeply enough to affect the hair bulbs, which are the treatment target,[20] and small lesions typically also regrow spontaneously. Oral corticosteroids may decrease the hair loss, but only for the period during which they are taken, and these medications can cause serious side effects.[20] No one treatment is effective in all cases, and some individuals may show no response to any treatment.[39]

For more severe cases, studies have shown promising results with the individual use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate or adjunct use with corticosteroids.[40]

When alopecia areata is associated with celiac disease, treatment with a gluten-free diet allows for complete and permanent regrowth of scalp and other body hair in many people, but in others, remissions and recurrences are seen.[27] This improvement is probably due to the normalization of the immune response as a result of gluten withdrawal from the diet.[27]

In June 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized baricitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, for the treatment of severe alopecia areata.[41]

Ritlecitinib (Litfulo) was approved for medical use in the United States in June 2023.[42]

Fecal matter transplants (FMT) have been shown to reverse AA and support hair growth, with long lasting results, even going as far as growing additional hair on arms and face while grey hairs even regained colour. This supports the idea of a connection between gut microbiota having a part in hair loss.[43]

Prognosis

In most cases that begin with a small number of patches of hair loss, hair grows back after a few months to a year.[21] In cases with a greater number of patches, hair can either grow back or progress to alopecia areata totalis or, in rare cases, alopecia areata universalis.[21]

No loss of body function occurs, and the effects of alopecia areata are psychological (loss of self-image due to hair loss), although these can be severe. Loss of hair also means the scalp burns more easily in the sun. Patients may also have aberrant nail formation because keratin forms both hair and nails.

Hair may grow back and then fall out again later. This may not indicate a recurrence of the condition, but rather a natural cycle of growth-and-shedding from a relatively synchronised start; such a pattern will fade over time. Episodes of alopecia areata before puberty predispose to chronic recurrence of the condition.[20]

Alopecia can be the cause of psychological stress. Because hair loss can lead to significant changes in appearance, individuals with it may experience social phobia, anxiety, and depression.[44]

Epidemiology

The condition affects 0.1%–0.2% of the population, with a lifetime risk of 1%-2%,[45] and is more common in females.[9]

Alopecia areata occurs in people who are otherwise healthy and have no other skin disorders.[20] Initial presentation most commonly occurs in the early childhood, late teenage years, or young adulthood, but can happen at any ages.[22] Patients also tend to have a slightly higher incidence of conditions related to the immune system, such as asthma, allergies, atopic dermatitis, and hypothyroidism.

Society and culture

The term alopecia, used by physicians dating back to Hippocrates, originates from the Greek word for fox, "alopex," and was so-named due to fur loss seen in fox mange. "Areata" is derived from the Latin word, "area," meaning a vacant space or patch.[46]

Alopecia areata and alopecia barbae have been identified by some as the biblical nethek condition that is part of the greater tzaraath family of skin disorders; the said disorders are purported to being discussed in the Book of Leviticus, chapter 13.[47]

Notable people

Actor Christopher Reeve suffered from the skin condition.[48] NASCAR driver Joey Logano, NFL Quarterback Josh Dobbs, obstacle athlete Kevin Bull,[49] politicians Peter Dutton[50] and Ayanna Pressley,[51] K-pop singer Peniel Shin of BtoB,[52] actors Anthony Carrigan[53] and Alan Fletcher,[54] and actresses Jada Pinkett Smith[55] and May Calamawy[56] all have some form of alopecia areata.

Research

Many medications are being studied.[57]

In 2014, preliminary findings showing that oral ruxolitinib, a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bone marrow disorder myelofibrosis, restored hair growth in three individuals with long-standing and severe disease.[58]

In March 2020, the US FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to baricitinib for the systematic treatment of alopecia areata[59] and granted approval in June 2022,[41] with a 32% efficacy rate for people with 50% hair loss reaching 80% scalp coverage in 36 weeks.[60] It acts as an inhibitor of janus kinase (JAK), blocking the subtypes JAK1 and JAK2.[61]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Alopecia Areata - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2004. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ "alopecia". The Chambers Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers. 2003. ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ↑ "alopecia". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ↑ "Definition of alopecia | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ "alopecia". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Alopecia Areata". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Liaison RF (May 2016). "Questions and Answers About Alopecia Areata". NIAMS. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Hordinsky M, Junqueira AL (June 2015). "Alopecia areata update". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery (Review). 34 (2): 72–5. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2015.0160. PMID 26176283.

- 1 2 3 Lundin M, Chawa S, Sachdev A, Bhanusali D, Seiffert-Sinha K, Sinha AA (April 2014). "Gender differences in alopecia areata". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 13 (4): 409–413. PMID 24719059.

- 1 2 3 Freire P, Riera R, Martimbianco A, Petri V, Atallah AN (September 2019). "Minoxidil for patchy alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 33 (9): 1792–1799. doi:10.1111/jdv.15545. PMID 30835901. S2CID 73460786.

- 1 2 3 Yee BE, Tong Y, Goldenberg A, Hata T (April 2020). "Efficacy of different concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 82 (4): 1018–1021. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.066. PMID 31843657. S2CID 209389315.

- 1 2 Erjavec SO, Gelfman S, Abdelaziz AR, Lee EY, Monga I, Alkelai A, et al. (February 2022). "Whole exome sequencing in Alopecia Areata identifies rare variants in KRT82". Nat Commun. 13 (1): 800. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13..800E. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28343-3. PMC 8831607. PMID 35145093.

- 1 2 Rajabi F, Drake L, Senna M, Rezaei N (2018). "Alopecia areata: A review of disease pathogenesis". British Journal of Dermatology. 179 (5): 1033–1048. doi:10.1111/bjd.16808. PMID 29791718. S2CID 43940520.

- ↑ Paggioli I, Moss J (December 2022). "Alopecia Areata: Case report and review of pathophysiology and treatment with Jak inhibitors". Journal of Autoimmunity. 133: 102926. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102926. PMID 36335798. S2CID 253320808.

- 1 2 Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J (February 2010). "Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 62 (2): 177–88, quiz 189–90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. PMID 20115945.

- ↑ Spano F, Donovan JC (September 2015). "Alopecia areata". Canadian Family Physician. 61 (9): 751–755. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 4569104. PMID 26371097.

- 1 2 Mounsey AL, Reed SW (August 2009). "Diagnosing and Treating Hair Loss". American Family Physician. 80 (4): 356–362. PMID 19678603. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 Beigi PK (2018). Alopecia Areata: A Clinician's Guide. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 9783319721347. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Freedberg IM, Fitzpatrick TB (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 978-0-07-138076-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alopecia Areata at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- 1 2 3 American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. Alopecia Areata. Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Dermatologic Disease Database. Aocd.org. Retrieved on 3 December 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Zoe Diana Draelos (30 August 2007), Alopecia Areata Archived 8 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. MedicineNet.com. Retrieved on 2 December 2007

- ↑ Wasserman D, Guzman-Sanchez DA, Scott K, McMichael A (February 2007). "Alopecia areata". International Journal of Dermatology. 46 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03193.x. PMID 17269961. S2CID 57279630.

- ↑ Lenane P, Pope E, Krafchik B (February 2005). "Congenital alopecia areata". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Case Reports. Review). 52 (2 Suppl 1): 8–11. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.024. PMID 15692503.

We believe AA should be classified not only as an acquired, but also a congenital form of nonscarring hair loss. It may well be more common than is thought because of lack of recognition

- ↑ Fukuyama M, Ito T, Ohyama M (January 2022). "Alopecia areata: Current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines". The Journal of Dermatology. 49 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16207. PMID 34709679. S2CID 240073350.

- ↑ Martinez-Mir A, Zlotogorski A, Gordon D, Petukhova L, Mo J, Gilliam TC, et al. (February 2007). "Genomewide scan for linkage reveals evidence of several susceptibility loci for alopecia areata". American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (2): 316–28. doi:10.1086/511442. PMC 1785354. PMID 17236136.

- 1 2 3 Caproni M, Bonciolini V, D'Errico A, Antiga E, Fabbri P (2012). "Celiac disease and dermatologic manifestations: many skin clue to unfold gluten-sensitive enteropathy". Gastroenterology Research and Practice (Review). 2012: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2012/952753. PMC 3369470. PMID 22693492.

- ↑ Tack GJ, Verbeek WH, Schreurs MW, Mulder CJ (April 2010). "The spectrum of celiac disease: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 7 (4): 204–13. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.23. PMID 20212505. S2CID 7951660.

- ↑ Duncan FJ, Silva KA, Johnson CJ, King BL, Szatkiewicz JP, Kamdar SP, et al. (February 2013). "Endogenous retinoids in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 133 (2): 334–43. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.344. PMC 3546144. PMID 23014334.

- ↑ Petukhova L, Duvic M, Hordinsky M, Norris D, Price V, Shimomura Y, et al. (July 2010). "Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity". Nature. 466 (7302): 113–7. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..113P. doi:10.1038/nature09114. PMC 2921172. PMID 20596022.

- ↑ Strazzulla LC, Wang EH, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. (2018). "Alopecia areata". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Elsevier BV. 78 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1141. ISSN 0190-9622. PMID 29241771.

- ↑ Lee S, Lee H, Lee CH, Lee W (2019). "Comorbidities in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Elsevier BV. 80 (2): 466–477.e16. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.013. ISSN 0190-9622. PMID 30031145. S2CID 51707882.

- ↑ Torales J, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A, Almirón-Santacruz J, Barrios I, O'Higgins M, et al. (June 2022). "Alopecia areata: A psychodermatological perspective". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 21 (6): 2318–2323. doi:10.1111/jocd.14416. ISSN 1473-2130. PMID 34449973. S2CID 237340798.

- ↑ Minokawa Y, Sawada Y, Nakamura M (January 2022). "Lifestyle Factors Involved in the Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (3): 1038. doi:10.3390/ijms23031038. PMC 8835065. PMID 35162962.

- ↑ Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M (July 2008). "Trichoscopy: a new method for diagnosing hair loss". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 7 (7): 651–654. PMID 18664157.

- ↑ Marks JG, Miller J (2006). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatology (4th ed.). Elsevier Inc. ISBN 978-1-4160-3185-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link). - ↑ Skin Conditions: Alopecia Areata Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. WebMD. Retrieved on 2 December 2007.

- 1 2 Shapiro J (December 2013). "Current treatment of alopecia areata". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Symposium Proceedings (Review). 16 (1): S42–4. doi:10.1038/jidsymp.2013.14. PMID 24326551.

- ↑ Alsantali A (July 2011). "Alopecia areata: a new treatment plan". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 4: 107–15. doi:10.2147/CCID.S22767. PMC 3149478. PMID 21833161.

- ↑ Anuset D, Perceau G, Bernard P, Reguiai Z (2016). "Efficacy and Safety of Methotrexate Combined with Low- to Moderate-Dose Corticosteroids for Severe Alopecia Areata". Dermatology. 232 (2): 242–248. doi:10.1159/000441250. PMID 26735937. S2CID 207742214.

- 1 2 "FDA Approves Lilly and Incyte's Olumiant (baricitinib) As First and Only Systemic Medicine for Adults with Severe Alopecia Areata" (Press release). Eli Lilly and Company. 13 June 2022. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022 – via PR Newswire.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Pfizer's Litfulo (Ritlecitinib) for Adults and Adolescents With Severe Alopecia Areata" (Press release). Pfizer. 23 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023 – via Business Wire.

- ↑ Barquero-Orias D, Muñoz Moreno-Arrones O, Vañó-Galván S (2021). "Alopecia and the Microbiome: A Future Therapeutic Target?". Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition). Elsevier BV. 112 (6): 495–502. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2021.03.011. ISSN 1578-2190. S2CID 234207277.

- ↑ Hunt N, McHale S (October 2005). "The psychological impact of alopecia". BMJ (Review). 331 (7522): 951–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. PMC 1261195. PMID 16239692.

- ↑ Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ (July 1995). "Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 70 (7): 628–33. doi:10.4065/70.7.628. PMID 7791384.

- ↑ Callander J, Yesudian PD (2018). "Nosological Nightmare and Etiological Enigma: A History of Alopecia Areata". International Journal of Trichology. 10 (3): 140–141. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_23_18. PMC 6028995. PMID 30034197.

- ↑ Rivkin P (September 2016). Alopecia Areata: Jewish Answers to a Modern Disease. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 18–33. ISBN 978-1-5375-2975-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Groopman J (2 November 2003). "The Reeve Effect". The New Yorker.

- ↑ "American alopecia ninja attacks awareness". Dermatology Times. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ Maiden S (27 May 2022). "Peter Dutton officially launches Liberal leadership campaign, reveals skin condition is alopecia". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Rep. Ayanna Pressley Reveals Beautiful Bald Head and Discusses Alopecia for the First Time". The Glow Up. 16 January 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ Kang Hee-jung (15 November 2016). ""탈모인 파이팅!" 프니엘, '안녕하세요' 출연 후기 게재" ["Fighting hair loss!" Peniel's review of'Hello' appeared]. News1 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Nedd A, Kibblesmith D, Bertozzi D (27 February 2015). "Gotham's Anthony Carrigan Talks Acting, Alopecia, And Learning To Love His Look". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Knox D (20 May 2022). "Alan Fletcher reveals alopecia to fans". TV Tonight. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ↑ Bellamy C (7 January 2022). "How Jada Pinkett Smith is uplifting Black women with alopecia". NBCBLK. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ↑ Calamawy M (11 June 2020). "Sharing My Alopecia Helped Me Set New Expectations for Myself". Glamour. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ↑ "Search - clinicaltrials.gov for alopecia areata". clinicaltrials.gov. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ Mohammadi D (2016). "A ray of hope for alopecia areata patients". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 296 (7889). doi:10.1211/PJ.2016.20201092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ "Lilly Receives FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for Baricitinib for the Treatment of Alopecia Areata" (Press release). Eli Lilly and Company. 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020 – via PR Newswire.

- ↑ "FDA Approves First Systemic Treatment for Alopecia Areata". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 13 June 2022. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Summary of opinion for Olumiant" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 15 December 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2016.