Maitrakas of Valabhi | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 475 CE–c. 776 CE | |||||||||||||||

_drachms._Late_5th-8th_century_Capped_head_right_in_Ksatrapa_style_Trident%253B_Brahmi_legend_around.jpg.webp) Coinage of Valabhi (Saurashtra), late 5th–8th century CE. Capped head right in Ksatrapa style. Trident with Brahmi legend around.

| |||||||||||||||

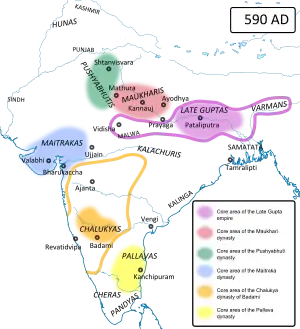

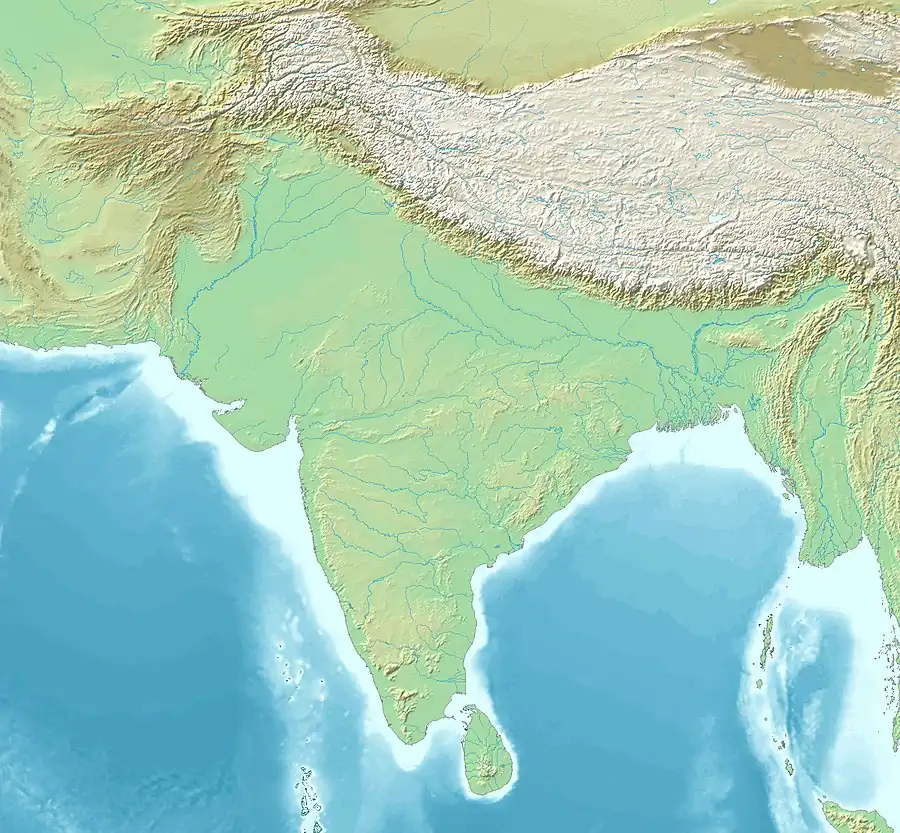

Maitrakas (in blue) and their contemporaries in India in 590 AD | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Vallabhi | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit Prakrit Sauraseni Apabhramsa | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism (Shaivism)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Paramabhataraka | |||||||||||||||

• c. 475–c. 493 CE | Bhatarka | ||||||||||||||

• c. 762–c. 776 CE | Siladitya VI | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 475 CE | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 776 CE | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Maitraka dynasty ruled western India (now Gujarat) from approximately 475 to approximately 776 CE from their capital at Vallabhi. With the sole exception of Dharapaṭṭa (the fifth king in the dynasty), who followed the Mithraic mysteries,[2] they were followers of Shaivism. Their origin is uncertain but they were probably Chandravanshi Kshatriyas.

Following the decline of the Gupta Empire, Maitraka dynasty was founded by Senapati (general) Bhaṭārka, who was a military governor of Saurashtra under Gupta Empire, who had established himself as the independent around 475 CE. The first two Maitraka rulers Bhaṭārka and Dharasena I used only the title of Senapati (general). The third ruler Droṇasiṁha declared himself as the Maharaja.[3] During the reign Dhruvasena I, Jain council at Vallabhi was probably held. The next ruler Dharapaṭṭa is the only ruler considered as a sun-worshipper. King Guhasena stopped using the term Paramabhattaraka Padanudhyata along his name like his predecessors, which denotes the cessation of displaying of the nominal allegiance to the Gupta overlords. He was succeeded by his son Dharasena II, who used the title of Mahadhiraja. His son, the next ruler Śilāditya I Dharmāditya was described by Hiuen Tsang, visited in 640 CE, as a "monarch of great administrative ability and of rare kindness and compassion". Śilāditya I was succeeded by his younger brother Kharagraha I.[4] Virdi copperplate grant (616 CE) of Kharagraha I proves that his territories included Ujjain. During the reign of the next ruler, Dharasena III, north Gujarat was included in this kingdom. Dharasena II was succeeded by another son of Kharagraha I, Dhruvasena II, Balāditya. He married the daughter of Harṣavardhana. His son Dharasena IV assumed the imperial titles of Paramabhattaraka Mahrajadhiraja Parameshvara Chakravartin. Sanskrit poet Bhatti was his court poet. The next powerful ruler of this dynasty was Śilāditya II. During the reign of Śilāditya V, Arabs probably invaded this kingdom. The last known ruler of this dynasty was Śilāditya VI.[3][5]

Maitrakas set up a Vallabhi University which came to be known far and wide for its scholastic pursuits and was compared with the Nalanda University. They came under the rule of Harṣa of Vardhana dynasty in the mid-seventh century, but retained local autonomy, and regained their independence after Harṣa's death. After repeated attacks by Arabs from the sea, the kingdom had weakened considerably. The dynasty ended by 783 CE. Apart from legendary accounts which connect fall of Vallabi with the Tajjika (Arab) invasions, no historical source mention how the dynasty ended.[6]

More than hundred temples of this period are known, mostly located along the western coast of Saurashtra.[7]

Origin

Early scholars like Fleet had misread copperplate grant and considered Maitrakas as some foreign tribe defeated by Bhaṭārka. Bhagwanlal Indraji believed that Maitrakas were foreign tribe while Bhaṭārka, who defeated them, belonged to the indigenous dynasty. Later readings corrected that Bhaṭārka was himself Maitraka who had succeeded in many battles. The earlier scholars had suggested the name Maitraka is derived from Mithra, the Sun or solar deity, and their supposed connection to Mihira and their sun-worshiping inclination.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Though Mitra and Mihira are synonyms for the sun, the Sanskrit literature does not use it in sense of sun-worshipers. Dharapaṭṭa is the fifth and the only king of all Maitraka kings connected with sun-worship. All other kings were followers of Shaivism.[2]

The copperplate grants do not help in identifying their origin, they describe only that the dynasty was born from a war-like tribe whose capital was at Vallabhi and they were Shaivas. Chinese traveler Hieun-Tsang visited Vallabhi during the second quarter of the 7th century had described the ruler as a Kshatriya.[15] Later Mahayana Buddhist work Manju-Shri-Mula-Kalpa had described them as Varavatya Yadava. The late Jain traditional work Shatrunjaya-Mahatmaya of Dhaneshwara describes Śilāditya as the Yadavas of Lunar race.[16]

Virji concludes that Maitrakas were a Kshatriya of Lunar race and their origin was probably from Mitra dynasty which once ruled region around Mathura (now in Uttar Pradesh, India). Several scholars like Benerjee, D. Shastri, D. R. Bhandarkar agree with her conclusion.[16]

Vallabhi

The Maitrakas ruled from their capital at Vallabhi.[7] They came under the rule of Harṣa in the mid-7th century, but retained local autonomy, and regained their independence after Harṣa's death.[17]

When I-Tsing, another Chinese traveller, visited Vallabhi in the last quarter of the seventh century, he found Vallabhi as a great center of learning including Buddhism. Gunamati and Sthiramati were two famous Buddhist scholars of Vallabhi in the middle of the seventh century. Vallabhi was famous for its liberalism and the students from all over the country, including the Brahmana boys, visited it to have higher education in secular and religious subjects. We are told that the graduates of Valabhi were given higher executive posts.

The Charanas of the region connect themselves with the last Maitraka ruler Śilāditya VI.[18] Goddess Khodiyar is considered a contemporary figure of the period when the Vallabhi kingdom declined in the 8th century AD.[19]

History

Bhaṭārka

The Senapati (general) Bhaṭārka, was a military governor of Saurashtra peninsula under Gupta Empire, who had established himself as the independent ruler of Gujarat approximately in the last quarter of 5th century when the Gupta empire weakened. He continued to use the title of Senapati (general). Apart from his military accomplishments, not much is known from the copper-plates. He was Śaiva according to the title Parama-Maheshwara used for him in grants by his descendants. It seems that he transferred the capital from Girinagar (Girnar) to Vallabhi.[20] The legends of all Valabhi coins are marked with Sri-Bhaṭārka. Almost all the Maitraka inscriptions start with his name. He is known only from the copperplate inscriptions of descendants.[21]

Dharasena I

%252C_National_Museum%252C_New_Delhi.jpg.webp)

Bhaṭārka was succeeded by his eldest son Dharasena I who also used only the title of Senapati (general). He reigned approximately from 174 to 180 Valabhi Era (VE) (c. 493–499 CE). It seems that he further consolidated power in weakening Gupta Empire. the Maitrkas had a marriage alliance with Harisena, the Vakataka king of Avanti who had himself captured many regions formerly under Guptas. Chandralekha, who is described in Dharasanasara of Devasena as the daughter of the king of Ujjayani and the queen of Dhruvasena I.[22]

Droṇasiṁha

Droṇasiṁha (c. 499 - c. 519 CE) was a younger brother of Dharasena I. He had declared himself as the Maharaja known from his copperplate dated 183 VE (502 CE). It is known that his coronation was attended by some higher authority, probably Vakataka as they had a marriage alliance.[23][24]

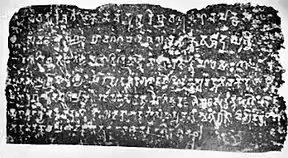

According to the Eran inscription of Gupta Empire ruler Bhanugupta (new revised translation published in 1981),[25] Bhanugupta and his chieftain or noble Goparaja participated in a battle against the "Maittras" in 510 CE, thought to be the Maitrakas (the reading being without full certainty, but "as good as certain" according to the authors).[25] This would directly allude to the conflict between the Maitrakas and the Guptas during the reign of Droṇasiṁha. The inscription reads:

- (Verses 3-4) (There is) the glorious Bhanugupta, a distinguished hero on earth, a mighty ruler, brave being equal to Partha. And along with him Goparaja, following (him) without fear, having overtaken the Maittras and having fought a very big and famous battle, went to heaven, becoming equal to Indra, the best of the gods; and (his) devoted, attached, beloved, and beauteous wife, clinging (to him), entered into the mass of fire (funeral pyre).

It is also around this time, or soon after, that the Alchon Huns king Toramana invaded Malwa, leading to his mention as "ruler of the earth" in the Eran boar inscription of Toramana.

Dhruvasena I

Dhruvasena I was the third son of Bhaṭārka and the younger brother of Droṇasiṁha. He reigned c. 519 - c. 549 CE. During his rule, Yashodharman of Malwa had defeated Harisena of the Vakataka dynasty, as well as the Huna king Mihirakula (in 528 CE). Dhruvasena probably had to acknowledge to overlord-ship of Yashodharman. It is known that they had regained their glory as Yashodharman's rule was short lived and was supplanted by the Guptas.[26]

In these grants, Dhruvasena's father Bhaṭárka and his elder brothers are described as 'great Máheśvaras' that are followers of Śiva, while Dhruvasena himself is called 'Paramabhágavata', the great Vaiṣṇava. He must be liberal in religious beliefs. In the 535 CE grant, he had made an arrangement for a Buddhist monastery at Valabhi built by his Buddhist niece Duḍḍá (or Lulá?). He had made several grants to Brahmanas of Vadnagar. The Jain council at Vallabhi was probably held during his rule which was arranged by his wife Chandralekha. During these days, he had lost his son as the Vallabhi council has condoled on loss.[27][15] Kalpa Sutra, the Jain text, was compiled probably during the reign of Dhruvasena, 980 or 993 years after the death (Nirvana) of Mahavira. Kalpa Sutra mentions that the public reading of it started at Anandapura (Vadnagar) to relieve Dhruvasena from the grief of the death of his son.[28] Based on his grants, it known that his kingdom extended from Dwarika to Valabhi, whole Saurashtra peninsula and as far as Vadnagar in the north.[29]

During his rule, the Garulakas or Garudakas had accepted the Maitrkas as their overlord. The Garulaka had captured Dwarika probably with help of the Maitrakas. They probably has an emblem of the Garuda and it his clear from their grants that they were Vaishnavas. They had made grants to Brahmanas and Buddhists alike.[27]

Dharapaṭṭa

Dhruvasena I was succeeded by his younger brother Dharapaṭṭa who reigned for a very short period, c. 549 to c. 553. He must be old when he ascended to the throne as his elder brothers ruled before him and thus his reign may have been short. He is the only ruler described as Paramaditya-Bhakta, the devotee of the sun god. He is known by the copperplate grants of his grandson.[30]

Guhasena

Dharapaṭṭa was succeeded by Guhasena who reigned from c. 553 to c. 569 CE. He must be great king as the all later ruler from Śilāditya I to the last ruler records his name in grants.[31]

Guhasena stopped using the term Paramabhattaraka Padanudhyata along his name like his predecessors, which denotes the cessation of displaying of the nominal allegiance to the Gupta overlords. He had assumed the title of Maharajadhiraja. During his early rule, the Maitraka kingdom was invaded by Maukhara or Maukhari king Ishwaravarman. The Raivataka (Girnar) hill is mentioned in his Jaunpur stone inscription but who won the war is unclear as the inscription is fragmentary. It is assumed that Guhasena must have repelled the attack.[32]

All his copper-plates record donations to Buddhist monasteries. He was a devotee of Shiva as mentioned in his grants and the copperplate bore the symbol of the Nandi, the vehicle of Shiva. He was interested in Buddhism in his last years of reign which is known from his grants. Guhasena wrote poems in Sanskrit, Prakrit and Saurseni Apabhramsa.[32]

Early historians had considered Gahlots (Gohil) of Mewar (Guhilas of Medapata) as his descendants. James Tod had recorded one such legend but epigraph evidence does not support the assumption. Virji also makes the point that Gahlots were Brahmanas as per their inscriptions while the Maitrakas were Kshatriyas.[32]

Dharasena II

Gahasena was succeeded by his son Dharasena II, who used the title of Samanta in his early grants and later readopts the title of Maharaja and later again as Mahasamanta. He reigned from 569 to 589–90 CE. It is considered that he had become subordinate to Maukhari ruler Ishanavarman for sometime between which reflect in the changes in titles. From Haraha inscription it known that Ishanavarman held sway over several rulers and Dharasena may have had to submit to him.[34]

He had made land grants to Brahmanas noted in his copperplate grants. One of his grants of 254 or 257 VE mentions solar eclipse which had helped in establish the dating of the Valabhi Era (VE). His one grant mentions Sthiramati, the Buddhist monk mentioned by Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang. One independent grant dated 574 CE made by Garulaka king Simhaditya is also found at Palitana along with him.[34]

Śīlāditya I

_in_National_Museum%252C_Delhi.jpg.webp)

Dharasena II was succeeded by Śīlāditya I who is also called Dharmāditya, the "sun of Dharma". He reigned from c. 590 - 615 CE. Manju-Sri-Mula-Kalpa assigns him thirty years. The Śatruñjaya Máhátmya has a prophetic account of one Śíláditya who will be a propagator of religion in Vikrama Saṃvat 477 (420 CE). The work is comparatively modern and does not correspond to chronology and dating of Maitraka kingdom. Although no reliance can be placed on the date still his second name Dharmáditya gives support to his identification with the Śíláditya of the Máhátmya.[15][35] Based on Manju-Sri-Mula-Kalpa and his grants, it is known that his rule extended from Malwa to the oceans of Kutch in western India.[36]

He was Shaiva. The one of his grant, to a temple of Śiva, has for its Dútaka the illustrious Kharagraha apparently the brother and successor of the king. He had made grants to sun temple and Buddhist monks show that he tolerated and respected Buddhism also. The writer of one of the grants is mentioned as the minister of peace and war Chandrabhaṭṭi; the Dútaka or causer of the gift in two of the Buddhist grants is Bhaṭṭa Ádityayaśas apparently some military officer. The Jain work Śatruñjaya Máhátmya mentions that its author was his preceptor. His equal treatment to all religions justifies his title Dharmāditya. The Śatruñjaya Máhátmya, though exaggerated, mentions that he had expelled some Buddhists from his kingdom sympathetic to his rival Harṣa. He is praised in accounts of Hiuen Tsang as a "monarch of great administrative ability and of rare kindness and compassion".[15][37][4]

He had a son named Derabhaṭṭa. He was succeeded by his younger brother Kharagraha I. It seems that there must have been a contest between his elder brother Upendra and him but finally Kharagraha I had succeeded. Derabhaṭṭa is mentioned to had helped Śilāditya is conquering some region between Sahya and Vindhya. He probably had helped Pulakeshin in a war against Kalachuris and may be gained the region as a result. He may have ruled the region independently till his death. His son and successor Śilāditya may have ruled the region as an arrangement with his brother Karagraha. A queen named Janjika is mentioned in one of copperplates which may be a wife of Śilāditya I.[38]

Kharagraha I

Śilāditya I was succeeded by his younger brother Kharagraha I, also known as Ishwaragraha.[39][4] Virdi copperplate grant (616 CE) of Kharagraha I proves that his territories included Ujjain which is mentioned as "victorious camp". He was probably in a continued struggle with Harṣa started during the reign of his brother. He was Śaiva and reigned c. 615 - 621 CE.[39]

Dharasena III

Kharagraha was succeeded by his son Dharasena III. He reigned from c. 621 to 627 CE. His only grant is made from the military camp at Kheṭaka (Kheda). Chapala mentioned in Manju-Sri-Mula-Kalpa as a successor of Śilāditya must be Dharasena III according to Virji while Jayaswal consider him as Kharagraha. He was Śaiva too. He had some gain in north Gujarat. He must have lost some power as his neighbouring kingdoms; Chalukya and Harshvardhan were in constant struggle.[40]

Dhruvasena II Balāditya

600 CE

After death of Dharasena III, he was succeeded by his younger brother Dhruvasena II also known as Balāditya, the "rising son". He reigned from c. 627-641 CE. He was well versed in grammar and the science of polity. Hiuen Tsang had written "a lively and hasty disposition and his wisdom and statecraft were shallow". He further adds that "he had attached himself to the precious three recently", viz. the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha of Buddhism. he had made grants to Buddhist Viharas and Hindu temples alike. He used the title of Paramamaheshwara, thus Shaiva. He had renewed the grant to the Kottammhikadevi, a Hindu temple, by his ancestor Droṇasiṁha. Dadda II, the Gurjara king of Lata had mentioned that he had given refuge to the Maitraka ruler in a struggle with Harṣa. But it is unclear that he was Dhruvasena II or Dharasena IV. Huien Tsang had mentioned that he had married the daughter of Harṣavardhan of Kanauj, probably as the marriage allegiance.[42][7]

His rule extended to Ratlam, a town west of Ujjain so whole modern central and north Gujarat were under the Maitrakas.[42]

Dharasena IV

Dharasena IV succeeded Dhruvasena II and reigned from c. 641 to 650 CE. He had subdued Gurjaras of Lata (south Gujarat) as he has issued copperplate grants from Bharuch. he had assumed the imperial titles of Paramabhattaraka Mahrajadhiraja Parameshvara Chakravartin. He had made grants to Buddhist Viharas and Brahmanas. He was a patron of scholars and the master archer. Probably during his reign, the Bhatti, the author of Bhattikavya or Ravanavadha, flourished. It is a grammatical poem.[43]

As Dharasena IV had no son, the succession transferred to the elder branch, Derabhaṭṭa lineage. He was succeeded by Dhruvasena III.[44]

Dhruvasena III

Dhruvasena III was a son of Derabhaṭṭa. He reigned from c. 650 to 654-655 CE. He had dropped the title of Chakravartin and was Shaiva. He may have lost his sway on Lata region to Chalukyas.[45]

Kharagraha II

Kharagraha II Dharamaditya was a successor of his younger brother Dhruvasena II. He had made a grant from military camp at Pulindaka which suggest that he was in a continued struggle with Chalukyas. He reigned from c. 655 to 658. He had no son.[46]

Śilāditya II

Śilāditya was a son of Śilāditya, the elder brother of Kharagraha II. As Kharagraha II had no son, he assumed the throne. He reigned from c. 658 to 685 CE. He has mentioned his father Derabhaṭṭa in his grants. He had probably recovered the Lata region from the Sendraka governor under the Chalukyas. The Chalukyas recovered the region under Vikramaditya I and placed his son Dharashraya Jayasimha as its governor. The region was still ruled by Gurjaras of Lata and Dadda III was probably in the constant struggle with the Maitrakas.[47]

Arab historians mention that the Arab commander Ismail had attacked the Ghogha in 677 CE (AH 57) but give no details. He must have been defeated by Śilāditya II.[48]

Śilāditya III

Śilāditya was a son and the successor of Śilāditya II. He reigned from c. 690 - 710 CE. Probably during this period, Panchasar held by Jayasekhara of Chavda dynasty was attacked.[49]

Muslim invasions and decline

Śilāditya IV

Śilāditya IV was a son of Śilāditya III who probably had Dharasena as his personal name. He ruled from c. 710 to 740 CE. Chalukya king Vikramaditya II had captured the Kheṭaka region from the Maitrakas with the presumed help of Jayabhatta IV, the Gurjara king of Lata. Sanjan plate of 733 CE informs that Rashtrakuta Indra I had forcefully married Chalukya princess Bhvanaga at Kaira (Kheda) so the region must be under them then.[50]

Biladuri, the Arab historian informs that the Maitraka kingdom was invaded by the Arabs under Junaid, Governor of the Caliphal province of Sind, during the Caliphate of Hisham (724-743 CE).[51] The invasion was carried out in 735-736 CE, and mentioned by the Gurjaras of Lata. The Muslims invaded all of the Gurjara region of north and south.[51] The Navsari plate of Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin mentions that the Tajjika (Arabs) had destroyed the Kachchelas (of Kutch), Saindhavas, Surastra, Chavotkata (Chavdas), Mauryas and Gurjaras (of Lata) and proceeded towards the Deccan. Jayabhatta helped the Maitrakas in battle at Valabhi at which they had defeated the Arabs but eventually lost. Finally at Navsari, the confederate army led by Chalukya troops routed the Arabs. Pulakeshin was awarded the titles of Dakshinapatha Svadharna, the solid pillar of the Deccan, Amvarta Kanivartayitr, the Repeller of the Unrepellable and Avanijanashraya, the refuge of the people.[52]

Śilāditya V

After the Arab invasion, the fragmented western states were organised under Śilāditya V. Malwa was lost to Gurjara-Pratiharas before the invasion. He probably had tried to recover Malwa as one of his grant (760 CE) is made from military camp at Godraka (Godhra). He must have failed to recover Malwa but nonetheless recovered the Kheṭaka (Kheda) region. He had to face another invasion of the Tajjika (Arabs) from the sea in 759 CE fighting for Umayyad Caliphate. The naval fleet under Amarubin Jamal was sent by Hasham, the governor of Sindh to the coast of Barda (the Barda hills near Porbandar). The invasion was defeated by the naval fleet of the Saindhava dynasty which was in allegiance with the Maitrakas. He reigned from c. 740 -762 CE.[53]

Śilāditya VI Dhrubhaṭa

_coinage._Late_5th-8th_century_Capped_head_right_in_Ksatrapa_style_Trident%253B_Brahmi_legend_around.jpg.webp)

Śilāditya VI, also known as Dhrubhaṭa, reigned c. 762 to c. 776 CE. As he had issued a grant from Anandpura (Vadnagar), it is assumed that he was on expansion again taking advantage of the prevailing situation in Rastrakutas and was in a struggle with the Gurjara-Pratiharas. Saurashtra was again invaded by the Tajjikas (Arabs) in 776 CE (AH 159). They captured the township of Barada but the epidemic broke out. The Arabs had to return and the Caliph had decided to stop further attempt to enter India. Agguka I of the Saindhava dynasty had claimed in his inscription a victory thus they had to withdraw. The Maitraka dynasty ended by c. 783 CE.[54][23][4][55] Apart from legendary accounts which connects fall of Vallabi with the Tajjika (Arab) invasions, no historical source mention how the dynasty ended.[56]

The governors of Girinagar (Girnar) and Vamanasthali (Vanthli) became independent and established their own dynasty on the fall of Vallabhi.[57]

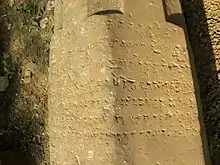

Religion

The Maitrakas were follower of the Shiva except Dhruvasena I who was Vaiṣnava and Dharapaṭṭa who was sun-worshiper. They all used title of parama-maheshwara before the names of king except those two. It is evident from the use of symbols like Nandi, the Bull and Trishula, the trident in their coins and inscriptions. There were presence of Vaishnavism and Goddess worship under their rule. There were large number of Buddhist Viharas in the Maitraka kingdom. Jains held their important Valabhi council here. The Maitrakas were tolerant to all religions and made donations and grants to all of them without partiality.[58]

Administration

There were administrative divisions managed by head of the division and helped by his subordinates. The highest division Vishaya were headed by Rashtrapati or Amatya and the lowest division Grama (equivalent to village) was headed by Gramakuta.[59]

Maitrakas set up a Vallabhi University which came to be known far and wide for its scholastic pursuits and was compared with the Nalanda University.[60]

Architecture

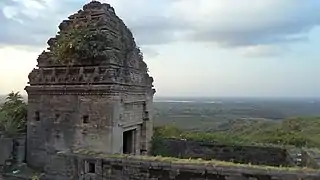

Temples and monuments

- Mentioned in the literary sources

The copper plate inscriptions of Maitrakas mentions religious edifices, Brahmanical as well as Buddhist. Some Buddhist monuments were constructed by the Maitrakas themselves. Some Brahmanical shrines includes Shiva temple at Vatapadra in Saurashtra (before 609 CE), Bhartishwara temple (extant in 631 CE), Goddess Kotammahika temple at Trisangamaka (extant in 639 CE, built during or before reign of Droṇasiṁha), Pandurarya temple at Hathab in Saurashtra (502 CE inscription). Other temples include Saptamatrika temple at Madasara-sthali (extant in 676 CE), Sun temple at Vatapadra (609 CE) and Bhadreniyaka (611 CE); all in Saurashtra.[7]

Several Buddhist monuments were built by Maitrakas. Majority of them were built in and around Vallabhi. Bhataraka probably the Bhataraka-vihara. Princess Dudda, sister of Dhruvasena I, built Dudda-vihara around the onset of the sixth century. Before 605 CE, Śilāditya I built Śilāditya-vihara Vamsakata in Saurashtra. Abhyantarika-vihara (before 567 CE) was built by a lady Mimma. Kakka Mankila added Kakka-vihara to Dudda-vihara mandala before 589 CE and another Gohaka-vihara was built there before 629 CE. The Yakshasura-vihara for nuns at Vallabhi was built around middle of the sixth century. Before 549 CE, Ajita, a merchant, built Ajita-vihara, probably besides the Yakshasura-vihara. Purnabhatta-vihara was built by Purnabhatta before 638 CE to the later group. Skandabhatta II, grandson of Mahasandhivigrahaka Sandabhatta I, built a Sandabhatta-vihara at Yodhavaka.[7]

Literary sources also mention some temples dedicated to the Jinas. Around 601 CE, Shantinatha temple at Vallabhi existed. At the time of destruction of Vallabhi, the images of Chandraprabha, Adinatha, Parshwanatha and Mahavira were transferred to safer places. The temples of Parshwanatha and Shantinatha existed at Vardhamana (Wadhwan) and Dostatika as well as probably the temple of Yakshi Ambika on the summit of Mount Girnar.[7]

Most of the constructions in this period were made of non-durable materials like bricks and wood. None of them survives now.[7]

- Extant temples

Firangi Deval at Kalsar

Firangi Deval at Kalsar%252C_From_East.jpg.webp) Magderu, Dhrasanvel, Okhamandal

Magderu, Dhrasanvel, Okhamandal Ruined temples at Sonkansari, Ghumli

Ruined temples at Sonkansari, Ghumli Temple at Sonkansari, Ghumli

Temple at Sonkansari, Ghumli

The architecture is in continuum of earlier Gupta period architecture found in caves at Uparkot and Khambhalida. More than hundred temples of this period is known. Almost all of them are located along the coastal belt of the western Saurashtra region except the one at Kalsar and few temples in the Barda hills region. Several temples of them are located in the territories controlled by the Saindhavas.[7]

The extant temples of this period are the temple at Gop, Sonkansari (Ghumli), Pachtar, Prachi, Firangi Deval at Kalsar, group of temples at Vasai near Dwarka, Kadvar, Bileshwar, Sutrapada, Visavada, Kinderkheda, Pata, Miyani, Pindara, Khimrana, two temples at Dhrasanvel (Magderu and Kalika Temple), two temples near Dhrewad (Kalika Mata Temple), Gayatri temple and Naga temple and Sun temple at Pasnavada, early temples at Junagadh, Gosa, Boricha, Prabhas Patan, Savri, Navadra, Suvarnatirth temple at Dwarka, Jhamra, Degam near Porbandar, Sarma near Ghed. Other extant temples include the temple groups at Khimeshwara, Shrinagar, Nandeshwara, Balej, Bhansara, Odadar; and the shrines at Bokhira, Chhaya, Visavada, Kuchadi, Ranavav, Tukada, Akhodar, Kalavad, Bhanvad, Pasthar, and Porbandar.[7]

Two kunds are known of this period, at Kadvar and Bhansara. The Shaivaite monastery at the Khimeshwara group of temples is the oldest known Brahminical monastery of India, preceding three centuries to that in central India.[7]

These temples are austere in their design and simple in decoration. They are important in architectural study to know the origin of Nagara-style shikhara and the beginning of their complex designs in temple architecture. These temples also point to the second of the two early Gujarat temple architecture schools; the north Gujarat early Nagara style and the Saurashtra style which initially influenced and ultimately ousted by the evolving Nagara style. The Saurashtra style disappeared by the tenth century.[7]

Coinage

The Maitrakas continued coinage styles established by their predecessors; the Guptas and the Western Kshatrapas. Large number of copper and silver coins are found in Vallabhi and elsewhere. There are two types of coins found. The first were 6" in diameter and weighted 29 grains. They were perhaps earlier coins modeled after the Western Kshatrapa coins. Later coins were similar to the Gupta coins in shape, size and legends. Like Gupta coins, they were not made of pure silver but silver-coated.[1]

The obverse of coin had the head of the kings facing right, as in Kshatrapa coins, but no legends or date. The reverse had Trishula, the trident, the emblem of Shiva. An axe (parashu) is added in reverse of some later coins. These symbols are surrounded by the legend in debased characters of Brahmi script.[1] It reads,

Rájño Mahákshatrapasa Bhatárakasa Mahesara–Śrí Bhaṭṭárakasa

or

Rájño, Mahákshatrapasa Bhatarakasa Mahesara Śrí Śarvva Bhaṭṭárakasa

Translation: "[This is a coin] of the illustrious the Shaivaite, Bhattaraka, the great king; the great Kshtrapa; the Lord and the devotee of Maheshwara.[1]

List of rulers

| History of Gujarat |

|---|

The list as follows:[4]

- Bhaṭārka (c. 470-c. 492)

- Dharasena I (c. 493-c. 499)

- Dronasinha (also known as Maharaja) (c. 500-c. 520)

- Dhruvasena I (c. 520-c. 550)

- Dharapaṭṭa (c. 550-c. 556)

- Gruhasena (c. 556-c. 570)

- Dharasena II (c. 570-c. 595)

- Śīlāditya I (also known as Dharmāditya) (c. 595-c. 615)

- Kharagraha I (c. 615-c. 626)

- Dharasena III (c. 626-c. 640)

- Dhruvasena II (also known as Balāditya) (c. 640-c. 644)

- Chakravarti king Dharasena IV (also known with the titles Param Bhaṭārka, Maharajadhiraja, Parameshwara) (c. 644-c. 651)

- Dhruvasena III (c. 650-c. 654-655)

- Kharagraha II (c. 655-c. 658)

- Śīlāditya II (c. 658- c. 685)

- Śīlāditya III (c. 690- c. 710)

- Śīlāditya IV (c. 710- c. 740)

- Śīlāditya V ( c. 740- c. 762)

- Śīlāditya VI Dhrubhaṭa ( c. 762- c. 776)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Virji 1955, p. 225–229.

- 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 17–18.

- 1 2 Hemchandra Raychaudhuri (2006). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Cosmo Publications. pp. 534–535. ISBN 978-81-307-0291-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Ancient India, S.Chand & Company, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, pp.594-6

- ↑ Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (2011). Ancient India. S Chand & Co Ltd. pp. 594–596. ISBN 978-8121908870. OCLC 941063107.

- ↑ Pusalkar, A. D.; Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra, eds. (1954). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Classical age. Vol. III. G. Allen & Unwin. p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Nanavati, J. M.; Dhaky, M. A. (1969-01-01). "The Maitraka and the Saindhava Temples of Gujarat". Artibus Asiae. Supplementum. 26: 3–83. doi:10.2307/1522666. JSTOR 1522666.

- ↑ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay, p 245, Bhau Daji (by Asiatic Society of Bombay, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Bombay Branch).

- ↑ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, 1904, p 142, 476, by Bombay (India : State); A Concise History of the Indian People, 1950, p 106, H. G. (Hugh George) Rawlinson.

- ↑ Advanced History of India, 1971, p 198, G. Srinivasachari; History of India, 1952, p 140.

- ↑ Views of Dr Fleet, Dr V. A. Smith, H. A. Rose, Peter N. Stearns and other scholars

- ↑ See: The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p 164, Dr Vincent Arthur Smith

- ↑ History of India, 1907, 284 A. V. Williams Jackson, Romesh Chunder Dutt, Vincent Arthur Smith, Stanley Lane-Poole, H. M. (Henry Miers) Elliot, William Wilson Hunter, Alfred Comyn Lyall.

- ↑ Also: Journal of the United Service Institution of India, United Service Institution of India, p331.

- 1 2 3 4 James Macnabb Campbell, ed. (1896). "I. THE CHÁVAḌÁS (A. D. 720–956.)". History of Gujarát. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Vol. I. Part I. The Government Central Press. pp. 85–86.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 19.

- ↑ History and Culture of Indian People, Classical age, p 150, (Ed) Dr A. D. Pusalkar, Dr R. C. Majumdar.

- ↑ Śāstrī, Hariprasāda Gaṅgāśaṅkara (2000). Gujarat Under the Maitrakas of Valabhī: History and Culture of Gujarat During the Maitraka Period, Circa 470-788 A.D. Oriental Institute. p. 101.

- ↑ Mitra, Sudipta (2005). Gir Forest and the Saga of the Asiatic Lion. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-183-2.

The Charans came next after the Ahirs and the existence of their goddess Khodiyar, a contemporary figure of the period when the Vallabhi kingdom declined in the 8th century AD, reveals the fact that the Charans came to Saurashtra before 1000 AD.

- ↑ Sinha, Nandini (2016-08-11). "Early Maitrakas, Landgrant Charters and Regional State Formation in Early Medieval Gujarat". Studies in History. 17 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1177/025764300101700201. S2CID 162126329.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 21–25.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 26–27.

- 1 2 Roychaudhuri, H.C. (1972). Political History of Ancient India, University of Calcutta, Calcutta, pp.553-4

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 28–30.

- 1 2 3 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol.3 (inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings) Main text p.352sq

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 31–33.

- 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 33–34.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 75.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 34.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 35–37.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 Virji 1955, p. 38–42.

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol 3 p.164ff

- 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 42–45.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 46–47.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 47.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 58–59.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 59–61.

- 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 63–64.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 65–69.

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 26,146. ISBN 0226742210.

- 1 2 Virji 1955, p. 71–75.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 71–80.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 80.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 81–82.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 83–84.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 85–88.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 88.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 90–93.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 94.

- 1 2 Petrie, Cameron A. (28 December 2020). Resistance at the Edge of Empires: The Archaeology and History of the Bannu basin from 1000 BC to AD 1200. Oxbow Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-78570-304-1.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 94–96.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 97–100.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 101–102.

- ↑ Richards, J.F. (1974). "The Islamic frontier in the east: Expansion into South Asia". Journal of South Asian Studies. 4 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1080/00856407408730690.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 102–105.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 105.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 165–186.

- ↑ Virji 1955, p. 230–247.

- ↑ Apte, D. G. (1950). Universities in ancient India. Raopura, Vadodara: Faculty of Education and Psychology, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. pp. 44–47 – via Cornell University Library.

Bibliography

- Virji, Krishnakumari Jethabhai (1955). Ancient history of Saurashtra: being a study of the Maitrakas of Valabhi V to VIII centuries A. D. Indian History and Culture Series. Konkan Institute of Arts and Sciences.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Parikh, Rasiklal Chhotalal; Shastri, Hariprasad Gangashankar, eds. (1974). ગુજરાતનો રાજકીય અને સાંસ્કૃતિક ઇતિહાસ: મૈત્રક કાલ અને અનુ-મૈત્રક કાલ [Political and Cultural History of Gujarat: Maitraka Era and Post-Maitraka Era]. Research Series - Book No. 68 (in Gujarati). Vol. III. Ahmedabad: Bholabhai Jeshingbhai Institute of Learning and Research.

.jpg.webp)