.jpg.webp)

Va'etchanan (וָאֶתְחַנַּן—Hebrew for "and I will plead," the first word in the parashah) is the 45th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the second in the Book of Deuteronomy. It comprises Deuteronomy 3:23–7:11. The parashah tells how Moses asked to see the Land of Israel, made arguments to obey the law, recounted setting up the Cities of Refuge, recited the Ten Commandments and the Shema, and gave instructions for the Israelites' conquest of the Land. The parashah is made up of 7,343 Hebrew letters, 1,878 Hebrew words, 122 verses, and 249 lines in a Torah Scroll (Sefer Torah).[1] Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in late July or August.[2]

It is always read on the special Sabbath Shabbat Nachamu, the Sabbath immediately after Tisha B'Av. As the parashah describes how the Israelites would sin and be banished from the Land of Israel, Jews also read part of the parashah, Deuteronomy 4:25–40, as the Torah reading for the morning (Shacharit) prayer service on Tisha B'Av, which commemorates the destruction of both the First Temple and Second Temple in Jerusalem.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the masoretic text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Va'etchanan has six "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashah Va'etchanan has several further subdivisions, called "closed portions" (סתומה, setumah) (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the open portion divisions. The first reading is divided by the first open portion. From the middle of the first reading to the middle of the second reading is the second open section. The third open portion concludes the second reading. The fourth open portion corresponds to the third reading. The fifth open portion spans the fourth and fifth readings. And the sixth open portion spans the sixth and seventh readings. Several closed portion divisions, notably one for every commandment, further divide the fourth and sixth readings.[3]

First reading—Deuteronomy 3:23–4:4

In the first reading, Moses pleaded with God to let him cross over and see the other side of the Jordan River.[4] But God was wrathful with Moses and would not listen, telling Moses never to speak of the matter again, and Moses blamed his punishment on the Israelites.[5] God directed Moses to climb the summit of Pisgah and look at the land.[6] And God told Moses to give Joshua his instructions and imbue him with strength and courage, for Joshua was to lead the people and allot to them the land.[7] The first open portion ends here with the end of the chapter.[8]

Moses exhorted the Israelites to heed God's laws, not to add anything to them, and not to take anything away from them, so that they might live to enter and occupy the land that God was giving them.[9] Moses noted that in the sin of Baal-peor, God wiped out every person who followed Baal-peor, while preserving alive those who held fast to God.[10] The first reading ends here.[11]

Second reading—Deuteronomy 4:5–40

In the second reading, Moses argued that observing the laws faithfully would prove to other peoples the Israelites' wisdom and discernment, for no other great nation had a god so close at hand as God, and no other great nation had laws as perfect as God's.[12]

Moses urged the Israelites to take utmost care not to forget the things that they saw, and to make them known to their children and children's children: How they stood before God at Horeb, the mountain was ablaze with flames, God spoke to them out of the fire, and God declared to them the Ten Commandments.[13] At the same time, God commanded Moses to impart to the Israelites laws for them to observe in the land that they were about to occupy.[14]

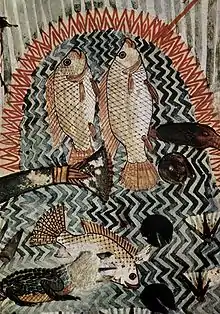

Because the Israelites saw no shape when God spoke to them out of the fire at Horeb, Moses warned them not to make for themselves a sculptured image in any likeness whatever—the form of a man, woman, beast, bird, creeping thing, or fish.[15] And when they looked up and saw the sun, moon, stars, and heaven, they were not to be lured into bowing down to them or serving them, for God allotted those things to other peoples, but God took the Israelites and brought them out of Egypt to be God's very own people.[16]

Moses said that God was angry with him on account of the Israelites, and God swore that Moses would not enter the land but would die in the land east of the Jordan.[17] Moses cautioned the Israelites not to forget the covenant that God concluded with them, and not to make a sculptured image, for God is a consuming fire, an impassioned God.[18] The second open portion ends here.[19]

Moses called heaven and earth to witness against the Israelites that should they make for themselves a sculptured image when they were in the land, then God would scatter them among the peoples, leaving only a scant few alive.[20] There in exile they would serve man-made gods of wood and stone, that would not be able to see, hear, eat, or smell.[21] But when they were in distress and they searched for God with all their heart and soul, returned to God, and obeyed God, then they would find God, even there.[22] For God is a compassionate God, Who would not fail them, let them perish, or forget the covenant that He made on oath with their fathers.[23]

Moses invited the Israelites to consider whether any people had ever heard the voice of a god speaking out of a fire and survived, or any god had taken one nation from the midst of another by prodigious acts and awesome power as their God had done for them in Egypt before their very eyes.[24] Moses said that it had been clearly demonstrated to them that the Lord alone is God and that there is none beside God.[25] Moses thus admonished them to observe God's laws and commandments, which Moses enjoined upon them that day, that it might go well with them and their children, and that they might long remain in the land that God was assigning to them for all time.[26] The second reading and the third open portion end here.[27]

Third reading—Deuteronomy 4:41–49

In the third reading, Moses set aside three cities of refuge on the east side of the Jordan to which a manslayer who unwittingly slew a person without having been hostile to him in the past could escape and live: Bezer among the Reubenites, Ramoth in Gilead among the Gadites, and Golan in Bashan among the Manassites.[28] The third reading and the fourth open portion end with Deuteronomy 4:49.[29]

Fourth reading—Deuteronomy 5:1–18 (or 5:1–22)

In the fourth reading,[30] Moses summoned the Israelites and called on them to hear the laws that he proclaimed that day, to study and observe them faithfully.[31] At Horeb, God made a covenant with them—not with their fathers, but with them, the living, every one of them.[32] God spoke to them face to face out of the fire on the mountain.[33] Moses stood between God and them to convey God's words to them, for they were afraid of the fire and did not go up the mountain.[34] A closed portion ends here.[29]

God said the Ten Commandments:

- "I the Lord am your God."[35]

- "You shall have no other gods beside Me. You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters below the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them."[36] A closed portion ends with Deuteronomy 5:10.[37]

- "You shall not swear falsely by the name of the Lord your God."[38] A closed portion ends here.[37]

- "Observe the Sabbath day and keep it holy."[39] A closed portion ends with Deuteronomy 5:15.[40]

- "Honor your father and your mother."[41] A closed portion ends here.[42]

- "You shall not murder." A closed portion ends here.[42]

- "You shall not commit adultery." A closed portion ends here.[42]

- "You shall not steal." A closed portion ends here.[42]

- "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor."[43] A closed portion ends here.[42]

- "You shall not covet your neighbor's wife. A closed portion ends here.[42] You shall not crave your neighbor's house, or his field, or his male or female slave, or his ox, or his ass, or anything that is your neighbor's."[44] The fourth reading and a closed portion ends here.[42]

Fifth reading—Deuteronomy 5:19 (23)–6:3

In the fifth reading, God spoke these words to the whole congregation at the mountain, with a mighty voice out of the fire and the dense clouds, and God inscribed them on two stone tablets, which God gave to Moses.[45] When the Israelites heard the voice out of the darkness and saw the mountain ablaze with fire, the tribal heads and elders asked Moses to hear all that God had to say and then tell the people, and they would willingly obey.[46] The fifth reading and the fifth open portion end with Deuteronomy 6:3.[47]

Sixth reading—Deuteronomy 6:4–25

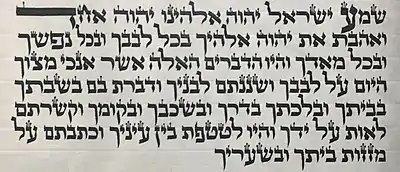

In the sixth reading, Moses imparted God's instructions, the Shema and V'ahavta, saying: "Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. And these words, which I command you this day, shall be upon your heart; and you shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when thou rise up. And you shall bind them for a sign upon your hand, and they shall be for frontlets between your eyes. And you shall write them upon the doorposts of your house, and upon your gates."[48] A closed portion ends here.[49]

Moses exhorted the Israelites, when God brought them into the land and they ate their fill, not to forget the God who freed them from bondage in Egypt, to revere and worship only God, and to swear only by God's name.[50] Moses warned the Israelites not to follow other gods, lest the anger of God wipe them off the face of the earth.[51] A closed portion ends here.[52]

Moses warned the Israelites not to try God, as they did at Massah, but to keep God's commandments and do what is right in God's sight, that it might go well with them, that they might be able to possess the land, and that all their enemies might be driven out before them.[53] A closed portion ends here.[54]

And when their children would ask the meaning of the commandments, they were to answer that they were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and God produced marvelous and destructive signs and portents, freed them with a mighty hand to give them the land, and then commanded them to observe all these laws for their lasting good and survival.[55] The sixth reading and a closed portion end with Deuteronomy 6:25.[56]

Seventh reading—Deuteronomy 7:1–11

In the seventh reading, Moses told the Israelites that when God brought them to the land and dislodged seven nations before them—the Hittites, Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites—the Israelites were to doom them to destruction, grant them no terms, and give them no quarter.[57] The Israelites were not to intermarry with them, for they would turn the Israelites' children away from God to worship other gods, and God's anger would wipe the Israelites out.[58] The Israelites were to tear down the nations' altars, smash their pillars, cut down their sacred posts, and consign their images to the fire.[59]

The Israelites were a people consecrated to God, and God chose them from all the peoples on earth to be God's treasured people.[60] God chose them not because they were the most numerous of peoples, but because God favored them and kept the oath God made with their fathers.[61] Moses told them to note that only God is God, the steadfast God who keeps God's covenant faithfully to the thousandth generation of those who love God and keep God's commandments, but who instantly requites with destruction those who reject God.[62] The maftir (מפטיר) reading concludes the parashah with Deuteronomy 7:9–11, and Deuteronomy 7:11 concludes the sixth open portion.[63]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to a different schedule.[64]

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 5

The early third millennium BCE Sumerian wisdom text Instructions of Shuruppak contains maxims that parallel the Ten Commandments, including:

- Don’t steal anything; don’t kill yourself! . . .

- My son, don’t commit murder . . .

- Don’t laugh with a girl if she is married; the slander (arising from it) is strong! . . .

- Don’t plan lies; it is discrediting . . .

- Don’t speak fraudulently; in the end it will bind you like a trap.[65]

Noting that Sargon of Akkad was the first to use a seven-day week, Professor Gregory S. Aldrete of the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay speculated that the Israelites may have adopted the idea from the Akkadian Empire.[66]

Deuteronomy chapter 6

Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3; Leviticus 20:24; Numbers 13:27 and 14:8; and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20 describe the Land of Israel as a land flowing "with milk and honey." Similarly, the Middle Egyptian (early second millennium BCE) tale of Sinuhe Palestine described the Land of Israel or, as the Egyptian tale called it, the land of Yaa: "It was a good land called Yaa. Figs were in it and grapes. It had more wine than water. Abundant was its honey, plentiful its oil. All kind of fruit were on its trees. Barley was there and emmer, and no end of cattle of all kinds."[67]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[68]

Deuteronomy chapter 4

Exodus 34:28 and Deuteronomy 4:13 and 10:4 refer to the Ten Commandments as the “ten words” (עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, aseret ha-devarim).

In Deuteronomy 4:20, Egypt is described as an "iron furnace." Solomon used the same image in his prayer in 1 Kings 8:51 at the dedication of the temple he built in Jerusalem.

In Deuteronomy 4:26, Moses called heaven and earth to serve as witnesses against Israel, and he did so again in Deuteronomy 30:19, 31:28, and 32:1. Similarly, Psalm 50:4–5 reports that God "summoned the heavens above, and the earth, for the trial of His people," saying "Bring in My devotees, who made a covenant with Me over sacrifice!" Psalm 50:6 continues: "Then the heavens proclaimed His righteousness, for He is a God who judges."

Deuteronomy chapter 5

Many commentators have called the account in Deuteronomy 5 a fuller narrative of the events briefly described in Exodus 20:18–21.[69]

The Sabbath

Deuteronomy 5:12–15 refers to the Sabbath. Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[70]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God's work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

The Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:8–11 commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:12–15 commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work—so that one's subordinates might also rest—and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook, and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one's place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make them ride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people abstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God's Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God's fury upon them, but God stayed God's hand.

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

To walk in God’s ways

The exhortation of Deuteronomy 5:30 to “walk in God’s ways” reflects a recurring theme also present in Deuteronomy 8:6; 10:12; 11:22; 19:9; 26:17; 28:9; and 30:16.

Deuteronomy chapter 6

Zechariah 14:9 echoes Deuteronomy 6:4, "The Eternal is our God, the Eternal alone," when the prophet foretells, "The Lord shall be King over all the earth; in that day there shall be one Lord with one name."[71]

In Joshua 22:5, Joshua quoted Deuteronomy 6:4–5 to the Reubenites, Gadites, and Manassites, cautioning them to take diligent heed to do the commandment and the law that Moses the servant of the Lord commanded.

Proverbs 6:20–22 parallels Deuteronomy 6:6–9.[72] Both Deuteronomy 6:6 and Proverbs 6:20 admonish the audience to heed the commandments—Deuteronomy 6:6 characterizing the commandments as instructions that Moses charged the Israelites, and Proverbs 6:20 as "your father's commandment" and "your mother's teaching." Both Deuteronomy 6:7 and Proverbs 6:22 speak of the commandments' presence while sleeping, waking, and traveling—with the commandments in Proverbs 6:22 taking on the active roles of leading, watching over, and talking. Both Deuteronomy 6:8 and Proverbs 6:21 speak of binding the commandments to one's person—Deuteronomy 6:8 to hand and forehead, Proverbs 6:21 to heart and throat.

In Deuteronomy 6:16, Moses cautioned the Israelites not test God. Similarly, in Malachi 3:15, the prophet Malachi criticized the people of his time who tempted God.

Deuteronomy chapter 7

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America read Exodus 34:6–7 and Numbers 14:18–20 to teach that God punishes children for their parents’ sins as a sign of mercy to the parents: When sinning parents repent, God defers their punishment to their offspring. Sommer argued that other Biblical writers, engaging in inner-Biblical interpretation, rejected that notion in Deuteronomy 7:9–10, Jonah 4:2, and Psalm 103:8–10. Sommer argued that Psalm 103:8–10, for example, quoted Exodus 34:6–7, which was already an authoritative and holy text, but revised the morally troubling part: Where Exodus 34:7 taught that God punishes sin for generations, Psalm 103:9–10 maintained that God does not contend forever. Sommer argued that Deuteronomy 7:9–10 and Jonah 4:2 similarly quoted Exodus 34:6–7 with revision. Sommer asserted that Deuteronomy 7:9–10, Jonah 4:2, and Psalm 103:8–10 do not try to tell us how to read Exodus 34:6–7; that is, they do not argue that Exodus 34:6–7 somehow means something other than what it seems to say. Rather, they repeat Exodus 34:6–7 while also disagreeing with part of it.[73]

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[74]

Deuteronomy chapter 4

With the Cities of Refuge in Deuteronomy 4:41–43 and 19:1–13 and Numbers 35:9–34, Divine intervention replaces a system of vengeance with a system of justice, much as in the play of the 5th century BCE Greek playwright Aeschylus The Eumenides, the third part of The Oresteia, Athena’s intervention helps to replace vengeance with trial by jury.

Deuteronomy chapter 5

Clement of Alexandria first used the Greek term that became the English word "Decalogue" to describe the Ten Commandments in about 200 C.E.[75]

1 Maccabees 2:27–38 told how in the 2nd century BCE, many followers of the pious Jewish priest Mattathias rebelled against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus's soldiers attacked a group of them on the Sabbath, and when the Pietists failed to defend themselves so as to honor the Sabbath (commanded in, among other places, Deuteronomy 5:12–15), a thousand died. 1 Maccabees 2:39–41 reported that when Mattathias and his friends heard, they reasoned that if they did not fight on the Sabbath, they would soon be destroyed. So they decided that they would fight against anyone who attacked them on the Sabbath.[76]

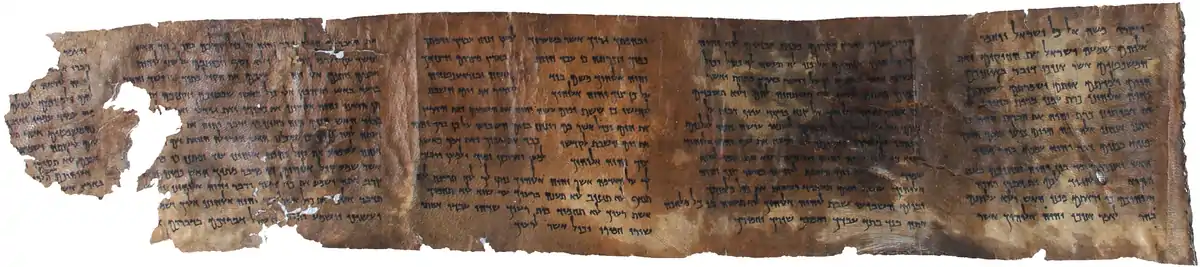

Echoing Deuteronomy 5:29,[77] "You shall observe to do therefore as the Lord your God has commanded you; you shall not turn aside to the right hand or to the left," the Community Rule of the Qumran sectarians provided, “They shall not depart from any command of God concerning their times; they shall be neither early nor late for any of their appointed times, they shall stray neither to the right nor to the left of any of His true precepts.”[78]

Deuteronomy chapter 6

Yigael Yadin observed that Qumran sectarians used tefillin and mezuzot quite similar to those in use today.[79]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[80]

Deuteronomy chapter 3

Noting that Deuteronomy 3:21 and 3:23 both use the same expression, "at that time," a Midrash deduced that the events of the two verses took place at the same time. Thus Rav Huna taught that as soon as God told Moses to hand over his office to Joshua, Moses immediately began to pray to be permitted to enter the Promised land. The Midrash compared Moses to a governor who could be sure that the king would confirm whatever orders he gave so long as he retained his office. The governor redeemed whomever he desired and imprisoned whomever he desired. But as soon as the governor retired and another was appointed in his place, the gatekeeper would not let him enter the king's palace. Similarly, as long as Moses remained in office, he imprisoned whomever he desired and released whomever he desired, but when he was relieved of his office and Joshua was appointed in his stead, and he asked to be permitted to enter the Promised Land, God in Deuteronomy 3:26 denied his request.[81]

The Gemara deduced from Moses's example in Deuteronomy 3:23 that one should seek a suppliant frame of mind before praying. Rav Huna and Rav Hisda were discussing how long to wait between recitations of the Amidah if one erred in the first reciting and needed to repeat the prayer. One said: long enough for the person praying to fall into a suppliant frame of mind, citing the words "And I supplicated the Lord" in Deuteronomy 3:23. The other said: long enough to fall into an interceding frame of mind, citing the words "And Moses interceded" in Exodus 32:11.[82]

Rabbi Simlai deduced from Deuteronomy 3:23–25 that one should always first praise God at the beginning of prayer, for Moses praised God in Deuteronomy 3:24 before he asked God in Deuteronomy 3:25 to let him see the good land.[83] Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Deuteronomy 3:26–27 that God let Moses see the Promised Land only because Moses prayed, and thus Rabbi Eleazar concluded that prayer is more effective than good deeds, for no one was greater in good deeds than Moses, and yet God let Moses see the land only after Moses prayed.[84]

Rabban Johanan ben Zakai interpreted the word "Lebanon" in Deuteronomy 3:25 to refer to the Temple in Jerusalem and "that goodly mountain" to refer to the Temple Mount. Thus one can interpret Deuteronomy 3:25 to say that Moses asked to see God's House.[85] Similarly, a Midrash interpreted the word "Lebanon" in Deuteronomy 3:25 to refer to the altar. Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai explained that the altar was called "Lebanon" because it made white (malbin) the sins of Israel, as indicated by the words of Isaiah 1:18: "though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white (yalbinu) as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool." Rabbi Tabyomi said that the altar was called "Lebanon" because all hearts (lebabot) rejoice there, as indicated by the words of Psalm 48:3: "Fair in situation, the joy of the whole earth, even Mount Zion." And the Rabbis said that the altar was called "Lebanon" because of the words of 1 Kings 9:3, which says of God and the Temple: "My eyes and My heart (libbi) shall be there perpetually.[86]

Another Midrash employed the understanding of "Lebanon" as the Temple to explain the role of gold in the world. Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish taught that the world did not deserve to have the use of gold. But God created gold for the sake of the Temple. The Midrash deduced this from the use of the word "good" in both Genesis 2:12, where it says, "the gold of that land is good," and Deuteronomy 3:25, where it says, "that goodly hill-country, and Lebanon."[87]

Rabbi Levi taught that God told Moses "enough!" in Deuteronomy 3:26 to repay Moses measure for measure for when Moses told Korah "enough!" in Numbers 16:3. The Gemara provided another explanation of the word "enough! (רַב, rav)" in Deuteronomy 3:26: God was telling Moses that Moses had a master (רַב, rav), namely Joshua, waiting to assume authority to lead the Israelites into the Promised Land, and thus Moses should not delay another master's reign by prolonging his own. The Gemara provided a third explanation of the word "enough!": God was telling Moses not to petition him anymore, so that people should not say: "How severe is the Master, and how persistent is the student." The Gemara explained why God was so hard on Moses with a Baraita taught in the School of Rabbi Ishmael: according to the camel is the burden; that is, a stronger, more righteous one must bear a greater burden.[88]

The School of Rabbi Ishmael taught that whenever Scripture uses the word "command" (צַו, tzav) (as Deuteronomy 3:28 does), it denotes exhortation to obedience immediately and for all time. A Baraita deduced exhortation to immediate obedience from the use of the word "command" in Deuteronomy 3:28, which says, "charge Joshua, and encourage him, and strengthen him." And the Baraita deduced exhortation to obedience for all time from the use of the word "command" in Numbers 15:23, which says, "even all that the Lord has commanded you by the hand of Moses, from the day that the Lord gave the commandment, and onward throughout your generations."[89]

Deuteronomy chapter 4

In Deuteronomy 4:1, Moses calls on Israel to heed the "statutes" (hukim) and "ordinances" (mishpatim). The Rabbis in a Baraita taught that the "ordinances" (mishpatim) were commandments that logic would have dictated that we follow even had Scripture not commanded them, like the laws concerning idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery, and blasphemy. And "statutes" (hukim) were commandments that the Adversary challenges us to violate as beyond reason, like those relating to shaatnez (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), halizah (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of the person with tzaraat (in Leviticus 14), and the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16). So that people do not think these "ordinances" (mishpatim) to be empty acts, Leviticus 18:4, which speaks of the "statutes" (hukim) and "ordinances" (mishpatim), says "I am the Lord," indicating that the Lord made these statutes, and we have no right to question them.[90]

The Gemara cited Deuteronomy 4:4 as an instance of where the Torah alludes to life after death. The Gemara related that sectarians asked Rabban Gamaliel where Scripture says that God will resurrect the dead. Rabban Gamaliel answered them from the Torah, the Prophets (Nevi'im), and the Writings (Ketuvim), yet the sectarians did not accept his proofs. From the Torah, Rabban Gamaliel cited Deuteronomy 31:16, "And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Behold, you shall sleep with your fathers and rise up [again].'" But the sectarians replied that perhaps Deuteronomy 31:16 reads, "and the people will rise up." From the Prophets, Rabban Gamaliel cited Isaiah 26:19, "Your dead men shall live, together with my dead body shall they arise. Awake and sing, you who dwell in the dust: for your dew is as the dew of herbs, and the earth shall cast out its dead." But the sectarians rejoined that perhaps Isaiah 26:19 refers to the dead whom Ezekiel resurrected in Ezekiel 27. From the Writings, Rabban Gamaliel cited Song of Songs 7:9, "And the roof of your mouth, like the best wine of my beloved, that goes down sweetly, causing the lips of those who are asleep to speak." (As the Rabbis interpreted Song of Songs as a dialogue between God and Israel, they understood Song of Songs 7:9 to refer to the dead, whom God will cause to speak again.) But the sectarians rejoined that perhaps Song of Songs 7:9 means merely that the lips of the departed will move. For Rabbi Johanan said that if a halachah (legal ruling) is said in any person's name in this world, the person's lips speak in the grave, as Song of Songs 7:9 says, "causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak." Thus Rabban Gamaliel did not satisfy the sectarians until he quoted Deuteronomy 11:21, "which the Lord swore to your fathers to give to them." Rabban Gamaliel noted that God swore to give the land not "to you" (the Israelites whom Moses addressed) but "to them" (the Patriarchs, who had long since died). Others say that Rabban Gamaliel proved it from Deuteronomy 4:4, "But you who did cleave to the Lord your God are alive every one of you this day." And (the superfluous use of "this day" implies that) just as you are all alive today, so shall you all live again in the World To Come.[91]

A Midrash taught that Deuteronomy 1:7, Genesis 15:18, and Joshua 1:4 call the Euphrates "the Great River" because it encompasses the Land of Israel. The Midrash noted that at the creation of the world, the Euphrates was not designated "great." But it is called "great" because it encompasses the Land of Israel, which Deuteronomy 4:7 calls a "great nation." As a popular saying said, the king's servant is a king, and thus Scripture calls the Euphrates great because of its association with the great nation of Israel.[92]

Bar Kappara interpreted Deuteronomy 4:9, "Only take heed to yourself," together with Deuteronomy 11:22, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you." Bar Kappara compared the soul and the Torah to a lamp, as Proverbs 20:27 says, "The soul of man is the lamp of the Lord," and Proverbs 6:23 says, "For the commandment is a lamp, and the teaching is light." God told humanity that God's light—the Torah—is in their hands, and their light—their souls—are in God's hands. God said that if people guard God's light, then God will guard their lights, but if people extinguish God's light, then God will extinguish their lights. For Deuteronomy 4:9 says, "Only take heed to yourself," and then "Keep your soul diligently." This explains Deuteronomy 11:22, "For if you shall diligently keep." The Midrash thus taught that "if you keep" (God's commandments), then "you shall be kept" (and your souls shall be guarded).[93]

A Baraita deduced from the words "you shall make them known to your children, and your children's children" in Deuteronomy 4:9 that if a parent teaches a child Torah, Scripture ascribes merit as though the parent had taught the child, the child's children, and so on, until the end of all time.[94] Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that if a parent teaches a child (or some say a grandchild) Torah, Scripture accounts it as if the parent had received the Torah at Mount Sinai, as Deuteronomy 4:9 says, "And you shall make them known to your children and your children's children," and immediately thereafter, Deuteronomy 4:10 says, "The day that you stood before the Lord your God in Horeb."[95] Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba once found Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, who had hurriedly thrown a cloth upon his head, taking his child (or some say grandchild) to the synagogue to study. When Rabbi Hiyya asked Rabbi Joshua what was going on, Rabbi Joshua replied that it was no small thing that the words "you shall make them known to your children and your children's children" are immediately followed by the words "The day that you stood before the Lord your God in Horeb." From then on, Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba did not eat breakfast before revising the previous day's lesson with his child (or some say grandchild) and adding another verse. And Rabbah son of Rav Huna did not eat breakfast until he took his child (or some say grandchild) to school.[94]

A Baraita deduced from the proximity of the words "And you shall make them known to your children and your children's children" in Deuteronomy 4:9 to the words "The day on which you stood before the Lord your God in Horeb" in Deuteronomy 4:10 that just as at Mount Sinai, the Israelites stood in dread, fear, trembling, and quaking, so when one teaches Torah to one's child, one should do so in dread, fear, trembling, and quaking.[96]

The Rabbis related Jacob's dream in Genesis 28:12–13 to Sinai. The "ladder" symbolizes Mount Sinai. That the ladder is "set upon (מֻצָּב, mutzav) the earth" recalls Exodus 19:17, which says, "And they stood (וַיִּתְיַצְּבוּ, vayityatzvu) at the nether part of the mount." The words of Genesis 28:12, "and the top of it reached to heaven," echo those of Deuteronomy 4:11, "And the mountain burned with fire to the heart of heaven." "And behold the angels of God" alludes to Moses and Aaron. "Ascending" parallels Exodus 19:3: "And Moses went up to God." "And descending" parallels Exodus 19:14: "And Moses went down from the mount." And the words "and, behold, the Lord stood beside him" in Genesis 28:13 parallel the words of Exodus 19:20: "And the Lord came down upon Mount Sinai."[97]

Rabbi Johanan counted ten instances in which Scripture refers to the death of Moses (including one in the parashah), teaching that God did not finally seal the harsh decree until God declared it to Moses. Rabbi Johanan cited these ten references to the death of Moses: (1) Deuteronomy 4:22: "But I must die in this land; I shall not cross the Jordan"; (2) Deuteronomy 31:14: "The Lord said to Moses: ‘Behold, your days approach that you must die'"; (3) Deuteronomy 31:27: "[E]ven now, while I am still alive in your midst, you have been defiant toward the Lord; and how much more after my death"; (4) Deuteronomy 31:29: "For I know that after my death, you will act wickedly and turn away from the path that I enjoined upon you"; (5) Deuteronomy 32:50: "And die in the mount that you are about to ascend, and shall be gathered to your kin, as your brother Aaron died on Mount Hor and was gathered to his kin"; (6) Deuteronomy 33:1: "This is the blessing with which Moses, the man of God, bade the Israelites farewell before his death"; (7) Deuteronomy 34:5: "So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, at the command of the Lord"; (8) Deuteronomy 34:7: "Moses was 120 years old when he died"; (9) Joshua 1:1: "Now it came to pass after the death of Moses"; and (10) Joshua 1:2: "Moses My servant is dead." Rabbi Johanan taught that ten times it was decreed that Moses should not enter the Land of Israel, but the harsh decree was not finally sealed until God revealed it to him and declared (as reported in Deuteronomy 3:27): "It is My decree that you should not pass over."[98]

Rabbi Jonah taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the world was created with a letter bet (the first letter in Genesis 1:1, which begins, בְּרֵאשִׁית, בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים, Bereishit bara Elohim, "In the beginning God created") because just as the letter bet is closed at the sides but open in front, so one is not permitted to investigate what is above and what is below, what is before and what is behind. Similarly, Bar Kappara reinterpreted the words of Deuteronomy 4:32 to say, "ask not of the days past, which were before you, since the day that God created man upon the earth," teaching that one may speculate from the day that days were created, but one should not speculate on what was before that. And one may investigate from one end of heaven to the other, but one should not investigate what was before this world.[99] Similarly, the Rabbis in a Baraita interpreted Deuteronomy 4:32 to forbid inquiry into the work of creation in the presence of two people, reading the words "for ask now of the days past" to indicate that one may inquire, but not two. The Rabbis reasoned that the words "since the day that God created man upon the earth" in Deuteronomy 4:32 taught that one must not inquire concerning the time before creation. The Rabbis reasoned that the words "the days past that were before you" in Deuteronomy 4:32 taught that one may inquire about the six days of creation. The Rabbis further reasoned that the words "from the one end of heaven to the other" in Deuteronomy 4:32 taught that one must not inquire about what is beyond the universe, what is above and what is below, what is before and what is after.[100]

Rabbi Eleazar read the words "since the day that God created man upon the earth, and ask from the one side of heaven" in Deuteronomy 4:32 to read, "from the day that God created Adam on earth and to the end of heaven." Thus Rabbi Eleazar read Deuteronomy 4:32 to intimate that when God created Adam in Genesis 1:26–27, Adam extended from the earth to the firmament. But as soon as Adam sinned, God placed God's hand upon Adam and diminished him, as Psalm 139:5 says: "You have fashioned me after and before, and laid Your hand upon me." Similarly, Rav Judah in the name of Rav taught that when God created Adam in Genesis 1:26–27, Adam extended from one end of the world to the other, reading Deuteronomy 4:32 to read, "Since the day that God created man upon the earth, and from one end of heaven to the other." (And Rav Judah in the name of Rav also taught that as soon as Adam sinned, God placed God's hand upon Adam and diminished him.) The Gemara reconciled the interpretations of Rabbi Eleazar and Rav Judah in the name of Rav by concluding that the distance from the earth to the firmament must equal the distance from one end of heaven to the other.[101]

Rabbi Levi addressed the question that Deuteronomy 4:33 raises: "Did ever a people hear the voice of God speaking out of the midst of the fire, as you have heard, and live?" (Deuteronomy 4:33, in turn, refers back to the encounter at Sinai reported at Exodus 19:18–19, 20:1, and after.) Rabbi Levi taught that the world would not have been able to survive hearing the voice of God in God's power, but instead, as Psalm 29:4 says, "The voice of the Lord is with power." That is, the voice of God came according to the power of each individual—young, old, or infant—to receive it.[102]

The Gemara counted only three verses in the Torah that indisputably refer to God's Kingship, and thus are suitable for recitation on Rosh Hashanah: Numbers 23:21, "The Lord his God is with him, and the shouting for the King is among them"; Deuteronomy 33:5, "And He was King in Jeshurun"; and Exodus 15:18, "The Lord shall reign for ever and ever." Rabbi Jose also counted as Kingship verses Deuteronomy 6:4, "Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God the Lord is One"; Deuteronomy 4:39, "And you shall know on that day and lay it to your heart that the Lord is God, . . . there is none else"; and Deuteronomy 4:35, "To you it was shown, that you might know that the Lord is God, there is none else beside Him"; but Rabbi Judah said that none of these three is a Kingship verse. (The traditional Rosh Hashanah liturgy follows Rabbi Jose and recites Numbers 23:21, Deuteronomy 33:5, and Exodus 15:18, and then concludes with Deuteronomy 6:4.)[103]

Rabbi Johanan taught that sorcerers are called כַשְּׁפִים, kashefim, because they seek to contradict the power of Heaven. (Some read כַשְּׁפִים, kashefim, as an acronym for כחש פמליא, kachash pamalia, "contradicting the legion [of Heaven].") But the Gemara noted that Deuteronomy 4:35 says, "There is none else besides Him (God)." Rabbi Hanina interpreted Deuteronomy 4:35 to teach that even sorcerers have no power to oppose God's will. A woman once tried to take earth from under Rabbi Hanina's feet (so as to perform sorcery against him). Rabbi Hanina told her that if she could succeed in her attempts, she should go ahead, but (he was not concerned, for) Deuteronomy 4:35 says, "There is none else beside Him." But the Gemara asked whether Rabbi Johanan had not taught that sorcerers are called כַשְּׁפִים, kashefim, because they (actually) contradict the power of Heaven. The Gemara answered that Rabbi Hanina was in a different category, owing to his abundant merit (and therefore Heaven protected him).[104]

Chapter 2 of tractate Makkot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the cities of refuge in Exodus 21:12–14, Numbers 35:1–34, Deuteronomy 4:41–43, and 19:1–13.[105]

The Mishnah taught that those who killed in error went into banishment. One would go into banishment if, for example, while one was pushing a roller on a roof, the roller slipped over, fell, and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while one was lowering a cask, it fell down and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while coming down a ladder, one fell and killed someone. But one would not go into banishment if while pulling up the roller it fell back and killed someone, or while raising a bucket the rope snapped and the falling bucket killed someone, or while going up a ladder one fell down and killed someone. The Mishnah's general principle was that whenever the death occurred in the course of a downward movement, the culpable person went into banishment, but if the death did not occur in the course of a downward movement, the person did not go into banishment. If while chopping wood, the iron slipped from the ax handle and killed someone, Rabbi taught that the person did not go into banishment, but the sages said that the person did go into banishment. If from the split log rebounding killed someone, Rabbi said that the person went into banishment, but the sages said that the person did not go into banishment.[106]

Rabbi Jose bar Judah taught that to begin with, they sent a slayer to a city of refuge, whether the slayer killed intentionally or not. Then the court sent and brought the slayer back from the city of refuge. The Court executed whomever the court found guilty of a capital crime, and the court acquitted whomever the court found not guilty of a capital crime. The court restored to the city of refuge whomever the court found liable to banishment, as Numbers 35:25 ordained, "And the congregation shall restore him to the city of refuge from where he had fled."[107] Numbers 35:25 also says, "The manslayer . . . shall dwell therein until the death of the high priest, who was anointed with the holy oil," but the Mishnah taught that the death of a high priest who had been anointed with the holy anointing oil, the death of a high priest who had been consecrated by the many vestments, or the death of a high priest who had retired from his office each equally made possible the return of the slayer. Rabbi Judah said that the death of a priest who had been anointed for war also permitted the return of the slayer. Because of these laws, mothers of high priests would provide food and clothing for the slayers in cities of refuge so that the slayers might not pray for the high priest's death.[108] If the high priest died at the conclusion of the slayer's trial, the slayer did not go into banishment. If, however, the high priests died before the trial was concluded and another high priest was appointed in his stead and then the trial concluded, the slayer returned home after the new high priest's death.[109]

Because Reuben was the first to engage in saving the life of his brother Joseph in Genesis 37:21, God decreed that the Cities of Refuge would be set up first within the borders of the Tribe of Reuben in Deuteronomy 4:43.[110]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer identified Og, king of Bashan, mentioned in Deuteronomy 4:47, with Abraham’s servant Eliezer introduced in Genesis 15:2 and with the unnamed steward of Abraham’s household in Genesis 24:2. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that when Abraham left Ur of the Chaldees, all the magnates of the kingdom gave him gifts, and Nimrod gave Abraham Nimrod’s first-born son Eliezer as a perpetual slave. After Eliezer had dealt kindly with Isaac by securing Rebekah to be Isaac’s wife, he set Eliezer free, and God gave Eliezer his reward in this world by raising him up to become a king—Og, king of Bashan.[111]

Deuteronomy chapter 5

Rabbi Azariah in the name of Rabbi Judah ben Rabbi Simon taught that the familiarity with which God spoke with the Israelites in Deuteronomy 5:4 befit the infancy of Israel's nationhood. Rabbi Azariah in the name of Rabbi Judah ben Rabbi Simon explained in a parable. A mortal king had a daughter whom he loved exceedingly. So long as his daughter was small, he would speak with her in public or in the courtyard. When she grew up and reached puberty, the king determined that it no longer befit his daughter's dignity for him to converse with her in public. So he directed that a pavilion be made for her so that he could speak with his daughter inside the pavilion. In the same way, when God saw the Israelites in Egypt, they were in the childhood of their nationhood, as Hosea 11:1 says, "When Israel was a child, then I loved him, and out of Egypt I called My son." When God saw the Israelites at Sinai, God spoke with them as Deuteronomy 5:4 says, "The Lord spoke with you face to face." As soon as they received the Torah, became God's nation, and said (as reported in Exodus 24:7), "All that the Lord has spoken will we do, and obey," God observed that it was no longer in keeping with the dignity of God's children that God should converse with them in the open. So God instructed the Israelites to make a Tabernacle, and when God needed to communicate with the Israelites, God did so from the Tabernacle. And thus Numbers 7:89 bears this out when it says, "And when Moses went into the tent of meeting that He might speak with him."[112]

Reading Exodus 20:1, “And God spoke all these words, saying,” the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that God spoke the ten commandments in one utterance, in a manner of speech of which human beings are incapable.[113]

The Mishnah taught that the priests recited the Ten Commandments daily.[114] The Gemara, however, taught that although the Sages wanted to recite the Ten Commandments along with the Shema in precincts outside of the Temple, they soon abolished their recitation, because the Sages did not want to lend credence to the arguments of the heretics (who might argue that Jews honored only the Ten Commandments).[115]

Rabbi Tobiah bar Isaac read the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6, "I am the Lord your God," to teach that it was on the condition that the Israelites acknowledged God as their God that God (in the continuation of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6) "brought you out of the land of Egypt." And a Midrash compared "I am the Lord your God" to a princess who having been taken captive by robbers, was rescued by a king, who subsequently asked her to marry him. Replying to his proposal, she asked what dowry the king would give her, to which the king replied that it was enough that he had rescued her from the robbers. (So God's delivery of the Israelites from Egypt was enough reason for the Israelites to obey God's commandments.)[116]

The Gemara taught that the Israelites heard the words of the first two commandments (in Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:7–8) directly from God. Rabbi Simlai expounded that a total of 613 commandments were communicated to Moses—365 negative commandments, corresponding to the number of days in the solar year, and 248 positive commandments, corresponding to the number of the parts in the human body. Rav Hamnuna said that one may derive this from Deuteronomy 33:4, "Moses commanded us Torah, an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob." The letters of the word "Torah" (תּוֹרָה) have a numerical value of 611 (as ת equals 400, ו equals 6, ר equals 200, and ה equals 5). And the Gemara did not count among the commandments that the Israelites heard from Moses the commandments, "I am the Lord your God," and, "You shall have no other gods before Me," as the Israelites heard those commandments directly from God.[117]

Rabbi Abbahu said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that when God gave the Torah, no bird twittered, no fowl flew, no ox lowed, none of the Ophanim stirred a wing, the Seraphim did not say (in the words of Isaiah 6:3) "Holy, Holy," the sea did not roar, the creatures did not speak, the whole world was hushed into breathless silence and the voice went forth in the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6: "I am the Lord your God."[118]

Rabbi Levi explained that God said the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6, "I am the Lord your God," to reassure Israel that just because they heard many voices at Sinai, they should not believe that there are many deities in heaven, but rather they should know that God alone is God.[119]

Rabbi Levi said that the section beginning at Leviticus 19:1 was spoken in the presence of the whole Israelite people, because it includes each of the Ten Commandments, noting that: (1) Exodus 20:2 says, "I am the Lord your God," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "I am the Lord your God"; (2) Exodus 20:3 says, "You shall have no other gods," and Leviticus 19:4 says, "Nor make to yourselves molten gods"; (3) Exodus 20:7 says, "You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain," and Leviticus 19:12 says, "And you shall not swear by My name falsely"; (4) Exodus 20:8 says, "Remember the Sabbath day," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "And you shall keep My Sabbaths"; (5) Exodus 20:12 says, "Honor your father and your mother," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "You shall fear every man his mother, and his father"; (6) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not murder," and Leviticus 19:16 says, "Neither shall you stand idly by the blood of your neighbor"; (7) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not commit adultery," and Leviticus 20:10 says, "Both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to death; (8) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not steal," and Leviticus 19:11 says, "You shall not steal"; (9) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not bear false witness," and Leviticus 19:16 says, "You shall not go up and down as a talebearer"; and (10) Exodus 20:14 says, "You shall not covet . . . anything that is your neighbor's," and Leviticus 19:18 says, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself."[120]

.jpg.webp)

Rabbi Ishmael interpreted Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:6–7 to be the first of the Ten Commandments. Rabbi Ishmael taught that Scripture speaks in particular of idolatry, for Numbers 15:31 says, "Because he has despised the word of the Lord." Rabbi Ishmael interpreted this to mean that an idolater despises the first word among the Ten Words or Ten Commandments in Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:6–7, "I am the Lord your God . . . . You shall have no other gods before Me."[121]

The Sifre taught that to commit idolatry is to deny the entire Torah.[122]

Tractate Avodah Zarah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws prohibiting idolatry in Exodus 20:3–6 and Deuteronomy 5:7–10.[123]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:8–11; 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:12.[124]

Noting that Exodus 20:8 says, "Remember the Sabbath day," and Deuteronomy 5:12 says, "Observe the Sabbath day," the Gemara taught that God pronounced both "Remember" and "Observe" in a single utterance, an utterance that the mouth cannot utter, nor the ear hear.[125] Rav Ada bar Ahabah taught that the Torah thus obligates women to sanctify the Sabbath (by reciting or hearing the Kiddush, even though women are generally not bound to observe such positive precepts that depend on specified times). For Scripture says both "Remember" and "Observe," and all who are included in the exhortation "Observe" are included in the exhortation "Remember." And women, since they are included in "Observe" (which the Rabbis interpret as a negative commandment that binds all Jews), are also included in "Remember."[126]

The Gemara reports that on the eve of the Sabbath before sunset, Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai and his son saw an old man running with two bundles of myrtle and asked him what they were for. The old man explained that they were to bring a sweet smell to his house in honor of the Sabbath. Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai asked whether one bundle would not be enough. The old man replied that one bundle was for “Remember” in Exodus 20:8 and one was for “Observe” in Deuteronomy 5:12. Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai told his son to mark how precious the commandments are to Israel.[127]

A Midrash deduced from similarities in the language of the creation of humanity and the Sabbath commandment that God gave Adam the precept of the Sabbath. Reading the report of God's creating Adam in Genesis 2:15, “And He put him (וַיַּנִּחֵהוּ, vayanihehu) into the Garden of Eden,” the Midrash taught that “And He put him (וַיַּנִּחֵהוּ, vayanihehu)” means that God gave Adam the precept of the Sabbath, for the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Exodus 20:11, “And rested (וַיָּנַח, vayanach) on the seventh day.” Genesis 2:15 continues, “to till it (לְעָבְדָהּ, le’avedah),” and the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Exodus 20:9, “Six days shall you labor (תַּעֲבֹד, ta’avod).” And Genesis 2:15 continues, “And to keep it (וּלְשָׁמְרָהּ, ule-shamerah),” and the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Deuteronomy 5:12, “Keep (שָׁמוֹר, shamor) the Sabbath day.”[128]

Rav Judah taught in Rav's name that the words of Deuteronomy 5:12, “Observe the Sabbath day . . . as the Lord your God commanded you” (in which Moses used the past tense for the word “commanded,” indicating that God had commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath before the revelation at Mount Sinai) indicate that God commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath when they were at Marah, about which Exodus 15:25 reports, “There He made for them a statute and an ordinance.”[129]

The Tanna Devei Eliyahu taught that if you live by the commandment establishing the Sabbath (in Exodus 20:8 and Deuteronomy 5:12), then (in the words of Isaiah 62:8) "The Lord has sworn by His right hand, and by the arm of His strength: ‘Surely I will no more give your corn to be food for your enemies." If, however, you transgress the commandment, then it will be as in Numbers 32:10–11, when "the Lord’s anger was kindled in that day, and He swore, saying: ‘Surely none of the men . . . shall see the land.’"[130]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[131]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed—the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[132]

A Midrash cited the words of Deuteronomy 5:14, "And your stranger who is within your gates," to show God's injunction to welcome the stranger. The Midrash compared the admonition in Isaiah 56:3, "Neither let the alien who has joined himself to the Lord speak, saying: 'The Lord will surely separate me from his people.'" (Isaiah enjoined Israelites to treat the convert the same as a native Israelite.) Similarly, the Midrash quoted Job 31:32, in which Job said, "The stranger did not lodge in the street" (that is, none were denied hospitality), to show that God disqualifies no creature, but receives all; the city gates were open all the time and anyone could enter them. The Midrash equated Job 31:32, "The stranger did not lodge in the street," with the words of Exodus 20:10, Deuteronomy 5:14, and Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates" (which implies that strangers were integrated into the midst of the community). Thus the Midrash taught that these verses reflect the Divine example of accepting all creatures.[133]

.jpg.webp)

The Mishnah taught that both men and women are obligated to carry out all commandments concerning their fathers.[134] Rav Judah interpreted the Mishnah to mean that both men and women are bound to perform all precepts concerning a father that are incumbent upon a son to perform for his father.[135]

A Midrash noted that almost everywhere, Scripture mentions a father's honor before the mother's honor. (See, for example, Deuteronomy 5:16 and 27:16 and Exodus 20:12.) But Leviticus 19:3 mentions the mother first to teach that one should honor both parents equally.[136]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita what it means to "honor" and "revere" one's parents within the meaning of Exodus 20:12 (honor), Leviticus 19:3 (revere), and Deuteronomy 5:16 (honor). To "revere" means that the child must neither stand nor sit in the parent's place, nor contradict the parent's words, nor engage in a dispute to which the parent is a party. To "honor" means that the child must give the parent food and drink and clothes, and take the parent in and out.[137]

Rabbi Tarfon taught that God came from Mount Sinai (or others say Mount Seir) and was revealed to the children of Esau, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them," and "Seir" means the children of Esau, as Genesis 36:8 says, "And Esau dwelt in Mount Seir." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall do no murder." The children of Esau replied that they were unable to abandon the blessing with which Isaac blessed Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword shall you live." From there, God turned and was revealed to the children of Ishmael, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "He shined forth from Mount Paran," and "Paran" means the children of Ishmael, as Genesis 21:21 says of Ishmael, "And he dwelt in the wilderness of Paran." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall not steal." The children of Ishmael replied that they were unable to abandon their fathers’ custom, as Joseph said in Genesis 40:15 (referring to the Ishamelites’ transaction reported in Genesis 37:28), "For indeed I was stolen away out of the land of the Hebrews." From there, God sent messengers to all the nations of the world asking them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:3 and Deuteronomy 5:7), "You shall have no other gods before me." They replied that they had no delight in the Torah, therefore let God give it to God's people, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength [identified with the Torah] to His people; the Lord will bless His people with peace." From there, God returned and was revealed to the children of Israel, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "And he came from the ten thousands of holy ones," and the expression "ten thousands" means the children of Israel, as Numbers 10:36 says, "And when it rested, he said, ‘Return, O Lord, to the ten thousands of the thousands of Israel.’" With God were thousands of chariots and 20,000 angels, and God’s right hand held the Torah, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At his right hand was a fiery law to them."[138]

Chapter 9 of Tractate Sanhedrin in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of murder in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17.[139] The Mishnah taught that one who intended to kill an animal but killed a person instead was not liable for murder. One was not liable for murder who intended to kill an unviable fetus and killed a viable child. One was not liable for murder who intended to strike the victim on the loins, where the blow was insufficient to kill, but struck the heart instead, where it was sufficient to kill, and the victim died. One was not liable for murder who intended to strike the victim on the heart, where it was enough to kill, but struck the victim on the loins, where it was not, and yet the victim died.[140]

Interpreting the consequences of murder (prohibited in Deuteronomy 5:17 and Exodus 20:13), the Mishnah taught that God created the first human (Adam) alone to teach that Scripture imputes guilt to one who destroys a single soul of Israel as though that person had destroyed a complete world, and Scripture ascribes merit to one who preserves a single soul of Israel as though that person had preserved a complete world.[141]

The Tanna Devei Eliyahu taught that if you live by the commandment prohibiting murder (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), then (in the words of Leviticus 26:6) "the sword shall not go through your land." If, however, you transgress the commandment, then (in God's words in Leviticus 26:33) "I will draw out the sword after you."[142]

Rav Aha of Difti said to Ravina that one can transgress the commandment not to covet in Deuteronomy 5:18 and Exodus 20:14 even in connection with something for which one is prepared to pay.[143]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael asked whether the commandment not to covet in Exodus 20:14 applied so far as to prohibit merely expressing one's desire for one's neighbor's things in words. But the Mekhilta noted that Deuteronomy 7:25 says, "You shall not covet the silver or the gold that is on them, nor take it for yourself." And the Mekhilta reasoned that just as in Deuteronomy 7:25 the word "covet" applies only to prohibit the carrying out of one's desire into practice, so also Exodus 20:14 prohibits only the carrying out of one's desire into practice.[144]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon distinguished the prohibition of Exodus 20:14, "You shall not covet," from that of Deuteronomy 5:18, "neither shall you desire." The Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon taught that the differing terms mean that one can incur liability for desiring in and of itself and for coveting in and of itself.[145]

Rabbi Isaac deduced from Deuteronomy 5:19 and 29:14 that all the Sages who arose in every generation after the Revelation at Sinai received their wisdom from that event. Rabbi Isaac read Deuteronomy 29:14 to teach that the prophets received from the Revelation at Sinai all the messages that they were to prophesy to subsequent generations. For Deuteronomy 29:14 does not say, "who are not here standing with us this day," but just "who are not with us this day." Rabbi Isaac taught that Deuteronomy 29:14 thus refers to the souls that were to be created thereafter; because these souls did not yet have any substance in them, they could not yet be "standing" at Sinai. But although these souls did not yet exist, they still received their share of the Torah that day. Similarly, Rabbi Isaac concluded that all the Sages who arose in every generation thereafter received their wisdom from the Revelation at Sinai, for Deuteronomy 5:19 says, "These words the Lord spoke to all your assembly . . . with a great voice, and it went on no more," implying that God's Revelation went on no more thereafter.[146]

Rabbi Tanchum ben Chanilai found in God's calling to Moses alone in Leviticus 1:1 proof that a burden that is too heavy for 600,000—hearing the voice of God (see Deuteronomy 5:22)—can be light for one.[147]

The Gemara cited Deuteronomy 5:27–28 to support the proposition that God approved of the decision of Moses to abstain from marital relations so as to remain pure for his communication with God. A Baraita taught that Moses did three things of his own understanding, and God approved: (1) He added one day of abstinence of his own understanding; (2) he separated himself from his wife (entirely, after the Revelation); and (3) he broke the Tables (on which God had written the Ten Commandments). The Gemara explained that to reach his decision to separate himself from his wife, Moses applied an a fortiori (kal va-chomer) argument to himself. Moses noted that even though the Shechinah spoke with the Israelites on only one definite, appointed time (at Mount Sinai), God nonetheless instructed in Exodus 19:10, "Be ready against the third day: come not near a woman." Moses reasoned that if he heard from the Shechinah at all times and not only at one appointed time, how much more so should he abstain from marital contact. And the Gemara taught that we know that God approved, because in Deuteronomy 5:27, God instructed Moses (after the Revelation at Sinai), "Go say to them, 'Return to your tents'" (thus giving the Israelites permission to resume marital relations) and immediately thereafter in Deuteronomy 5:28, God told Moses, "But as for you, stand here by me" (excluding him from the permission to return). And the Gemara taught that some cite as proof of God's approval God's statement in Numbers 12:8, "with him [Moses] will I speak mouth to mouth" (as God thus distinguished the level of communication God had with Moses, after Miriam and Aaron had raised the marriage of Moses and then questioned the distinctiveness of the prophecy of Moses).[148]

The Sifre interpreted the “ways” of God referred to in Deuteronomy 28:9 (as well as Deuteronomy 5:30; 8:6; 10:12; 11:22; 19:9; 26:17; and 30:16) by making reference to Exodus 34:6–7, “The Lord, the Lord, God of mercy and grace, slow to wrath and abundant in mercy and truth, keeping lovingkindness for thousands, forgiving transgression, offense, and sin, and cleansing . . . .” Thus the Sifre read Joel 3:5, “All who will be called by the name of the Lord shall be delivered,” to teach that just as Exodus 34:6 calls God “merciful and gracious,” we, too, should be merciful and gracious. And just as Psalm 11:7 says, “The Lord is righteous,” we, too, should be righteous.[149]

Deuteronomy chapter 6

The Gemara reported a number of Rabbis' reports of how the Land of Israel did indeed flow with "milk and honey," as described in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3; Leviticus 20:24; Numbers 13:27 and 14:8; and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. Once when Rami bar Ezekiel visited Bnei Brak, he saw goats grazing under fig trees while honey was flowing from the figs, and milk dripped from the goats mingling with the fig honey, causing him to remark that it was indeed a land flowing with milk and honey. Rabbi Jacob ben Dostai said that it is about three miles from Lod to Ono, and once he rose up early in the morning and waded all that way up to his ankles in fig honey. Resh Lakish said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey of Sepphoris extend over an area of sixteen miles by sixteen miles. Rabbah bar Bar Hana said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey in all the Land of Israel and the total area was equal to an area of twenty-two parasangs by six parasangs.[150]

The first three chapters of tractate Berakhot in the Mishnah, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud and the first two chapters of tractate Berakhot in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of the Shema in Deuteronomy 6:4–9 and 11:13–21.[151]

Already at the time of the Mishnah, Deuteronomy 6:4–9 constituted the first part of a standard Shema prayer that the priests recited daily, followed by Deuteronomy 11:13–21 and Numbers 15:37–41.[152]

The Rabbis taught that saying the words of Deuteronomy 6:4, "Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One," and no more, constituted Rabbi Judah the Prince's recital of the Shema. Rav once told Rabbi Hiyya that he had not witnessed Rabbi Judah the Prince accept upon himself the yoke of the Heaven by reciting the Shema. Rabbi Hiyya replied to Rav that in the moment that Rabbi Judah the Prince passed his hand to cover his eyes to recite, "Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One," he accepted upon himself the yoke of the kingdom of Heaven.[153]

Rabbi Joshua ben Korhah taught that in the Shema, Jews recite the words of Deuteronomy 6:4–9 ("Here, O Israel . . . ," Shema Yisrael . . .) before those of Deuteronomy 11:13–21 ("And it shall come to pass . . . ," VeHaya im Shamoa . . .) so that one first accepts the yoke of Heaven by proclaiming the Unity of God and then accepts the yoke of the commandments by saying the words, "If you shall diligently heed all My commandments." Jews recite the words of Deuteronomy 11:13–21 ("And it shall come to pass . . . ," VeHaya im Shamoa . . .) before those of Numbers 15:37–41 ("And the Lord said . . . ," VaYomer . . .) because Deuteronomy 11:13–21 is applicable both in the day and the night (since it mentions all the commandments), whereas Numbers 15:37–41 is applicable only in the day (since it mentions only the precept of fringes, tzitzit, which is not obligatory by night).[154]

The Mishnah taught that the absence of one of the two portions of scripture in the mezuzah—Deuteronomy 6:4–8 and 11:13–21—invalidates the other, and indeed even one imperfect letter can invalidates the whole.[155]

The Mishnah taught that the absence of one of the four portions of scripture in the Tefillin—Exodus 13:1–10 and 11–16 and Deuteronomy 6:4–8 and 11:13–21—invalidates the others, and indeed even one imperfect letter can invalidate the whole.[155]

Reading Deuteronomy 6:4, "Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One," the Rabbis taught that God told Israel that all that God had created, God created in pairs: heaven and earth, sun and moon, Adam and Eve, this world and the World To Come. But God's Glory is One and Unique in the world.[156]

Rabbi Isaac linked the words "the Lord our God" in Deuteronomy 6:4 with Lamentations 3:24, "The Lord is my portion, says my soul." Rabbi Isaac compared this to a king who entered a province with his generals, officials, and governors. Some of the citizens of the province chose a general as their patron, others an official, and others a governor. But the one who was cleverer than the rest chose the king as his patron, as all the other officials were liable to be changed, but the king would remain the king. Likewise, when God came down on Sinai, there also came down with God many companies of angels, Michael and his company, and Gabriel and his company. Some of the nations of the world chose Michael as their patron, and others chose Gabriel, but Israel chose God, exclaiming the words of Lamentations 3:24, "The Lord is my portion, says my soul," and this is the force of the words "the Lord our God" in Deuteronomy 6:4.[157]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah read Deuteronomy 6:4, "Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One," to indicate that Israel has made God the sole object of Israel's love in the world. God, in turn, makes Israel the special object of God's love in the world, as 2 Samuel 7:23 and 1 Chronicles 17:21 say, "And who is like Your people, like Israel, a nation one in the earth."[158]

The Gemara explained that when Jews recite the Shema, they recite the words, "blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom for ever and ever," quietly between the words, "Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one," from Deuteronomy 6:4, and the words, "And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might," from Deuteronomy 6:5, for the reason that Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish expounded when he explained what happened in Genesis 49:1. That verse reports, "And Jacob called to his sons, and said: ‘Gather yourselves together, that I may tell you what will befall you in the end of days.'" According to Rabbi Simeon, Jacob wished to reveal to his sons what would happen in the end of the days, but just then, the Shechinah departed from him. So Jacob said that perhaps, Heaven forefend, he had fathered a son who was unworthy to hear the prophecy, just as Abraham had fathered Ishmael or Isaac had fathered Esau. But his sons answered him (in the words of Deuteronomy 6:4), "Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One," explaining that just as there was only One in Jacob's heart, so there was only One in their hearts. And Jacob replied, "Blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom for ever and ever." The Rabbis considered that Jews might recite "Blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom for ever and ever" aloud, but rejected that option, as Moses did not say those words in Deuteronomy 6:4–5. The Rabbis considered that Jews might not recite those words at all, but rejected that option, as Jacob did say the words. So the Rabbis ruled that Jews should recite the words quietly. Rabbi Isaac taught that the School of Rabbi Ammi said that one can compare this practice to that of a princess who smelled a spicy pudding. If she revealed her desire for the pudding, she would suffer disgrace; but if she concealed her desire, she would suffer deprivation. So her servants brought her pudding secretly. Rabbi Abbahu taught that the Sages ruled that Jews should recite the words aloud, so as not to allow heretics to claim that Jews were adding improper words to the Shema. But in Nehardea, where there were no heretics so far, they recited the words quietly.[159]

Rabbi Phinehas ben Hama taught that the Israelites merited to recite the Shema at the Revelation on Sinai, for it was with the word Shema that God first began to speak at Sinai when God said in Deuteronomy 5:1, 6: "Hear, O Israel . . . I am the Lord your God," and the Israelites all answered with the words of Deuteronomy 6:4: "The Lord our God, the Lord is One." And Moses said, "Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever."[160]

The Rabbis told that when Moses ascended to heaven, he heard the ministering angels saying to God, "Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever." Moses brought this declaration down to Israel. Rav Assi explained why Jews do not make this declaration aloud, comparing this to a man who took jewelry from the royal palace and gave it to his wife, telling her not to wear it in public, but only in the house. But on the Day of Atonement, when Jews are as pure as the ministering angels, they do recite the declaration aloud.[161]

Rabbi Johanan considered twice daily recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9) to fulfill the commandment of Joshua 1:8 that "this book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night." Rabbi Jose interpreted the analogous term "continually" (תָּמִיד, tamid) in Exodus 25:30, which says "And on the table you shall set the bread of display, to be before [God] continually." Rabbi Jose taught that even if they took the old bread of display away in the morning and placed the new bread on the table only in the evening, they had honored the commandment to set the bread "continually." Rabbi Ammi analogized from this teaching of Rabbi Jose that people who learn only one chapter of Torah in the morning and one chapter in the evening have nonetheless fulfilled the precept of Joshua 1:8 that "this book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night." And thus Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that even people who read just the Shema morning and evening thereby fulfill the precept of Joshua 1:8. Rabbi Johanan taught that it is forbidden, however, to teach this to people who through ignorance are careless in the observance of the laws (as it might deter them from further Torah study). But Rava taught that it is meritorious to say it in their presence (as they might think that if merely reciting the Shema twice daily earns reward, how great would the reward be for devoting more time to Torah study).[162]

A Midrash warned that if one changed the Hebrew letter dalet (ד) in the word אחד, echad ("one") in Deuteronomy 6:4 into the letter resh (ר) (changing the word from "one" to "strange") one could cause the destruction of the Universe.[163]

A Midrash interpreted Song of Songs 2:9, "My beloved is like a gazelle or a young hart; behold, he stands behind our wall," to apply to God's Presence in the synagogue. The Midrash read the words, "behold, He stands behind our wall," to allude to the occasion in Genesis 18:1 when God came to visit Abraham on the third day after Abraham's circumcision. Genesis 18:1 says, "And the Lord appeared to him by the terebinths of Mamre, as he sat (יֹשֵׁב, yoshev) . . . ." The word for "he sat" is in a form that can be read yashav, the letter vav (ו) being omitted, as though it read that Abraham was sitting before he saw God, but on seeing God, he wanted to stand up. But God told him to sit, as Abraham would serve as a symbol for his children, for when his children would come into their synagogues and houses of study and recite the Shema, they would be sitting down and God's Glory would stand by. To support this reading, the Midrash cited Psalm 82:1, "God stands in the congregation of God."[164]