The economic de-industrialisation of India refers a period of reduction in industrial based activities within the Indian economy from 1757 to 1947. The process of de-industrialisation is an economic change in which employment in the manufacturing sector declines due to various economic or political reasons.[1] The decline in employment in manufacturing is also followed by the fall in the share of manufacturing value added in GDP. The process of de-industrialisation can be due to development and growth in the economy and it can also occur due to political factors.

The initial concept of Indian de-industrialisation was introduced by Sir William Bentinck who acted as the Governor-General of India between 1833 and 1835. His policy significantly impacted the cotton industry of India. The effect of British cotton industry on Indian cotton industry was originally presented by Karl Marx in Das Kapital.[2]

The deindustrialisation of India started when the Indian economy was colonised under the British Empire. The Indian economy was ruled under the British East Indian Company Rule from 1757 to 1858. This ruling period mainly involved British protectionist policies, restricting sales of Indian goods and services within Britain while exposing Indian markets to British goods and services, including the introduction of machine-made goods, without tariffs and quotas. By the 19th century, the British empire had overtaken the Indian economy as the world's largest textile manufacturer. From 1858, the Indian economy was ruled directly under the British imperial rule, also known as the Rule under the British Raj. India continued to be ruled directly under the British until the end of the colonial period in 1947.

Some scholars theorize that the de-industrialisation processes observed in India were a product of colonial rule. The Industrial Revolution in Europe was followed by a significant decline in the artisan and manufacturing activities in several European colonies in Asia such as India.[3]

Indian economy between 1600 and 1800

Prior to the colonisation of India, the country had reached significant fineness in the production of luxury products in the form of handicrafts. These luxury goods consisted of cotton, silk, and ivory which had a significant market in Europe.[4] Before mercantilism, these products were transferred to the European market through Arab traders and these products were considered very significant in bringing gold, silver and other valuable exchange items into the Arab countries. During the period of Mercantilism, the link between European markets and Indian subcontinent became more direct and trade became easier. The rising import of Indian cotton into Europe created significant competition for the British wool industry.[5]

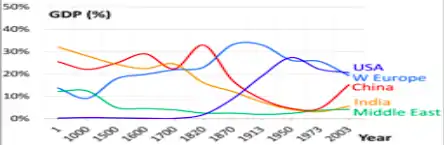

The GDP per capita of India, as a percent of the British level, declined during the seventeenth and eighteenth century period from over 60% of the British level to 15% by 1871.[6] The period from 1600 to 1871 saw an annual population growth rate of 0.22%. Industry and commerce grew rapidly during the same phase, driven particularly by exports. The production of Mughal India was around 25% of the global industry output in the early phase of 18th century. The major products exported to Europe included indigo, cotton textiles, spices, silks and peppers. The wealthiest province of Bengal Subah which generated 50% of the GDP and 12% world GDP was prominent in textile manufacturing, especially Muslin trade.[6] Indian cultivators began extensive cultivation of maize and tobacco with increased yields due to improvements in the irrigation system. The growth in the agriculture sector expanded slowly and since it was the largest sector, total output growth was quite modest. The major exports in the manufacturing industry included steel, shipbuilding and textiles. This led to the steady reduction in GDP per capita during this period before stabilizing a bit in the 19th century.

With the introduction of British East India Company and after collection of right to revenue rights, it stopped importing gold and silver earlier used in payment for exports from India. The period from 1780 to 1860 saw dynamic shift of India's economy from processed goods exporter to raw materials and buyer of manufactured goods. Fine cotton silk exported was shifted to raw materials consisting opium, indigo and raw cotton. The cotton mill industries of the British even began to lobby government for import tax to India. The infrastructure created by the British colonial government, including legal systems, railways and telegraphs are considered towards resource exploitation, leaving industrial growth static and agriculture unable to keep up with growing population. The industry output from India declined to 2% of world's output in 1900. Britain also replaced India as the largest textile manufacturer of the world.

The economy of the Mughal Empire is well known for the building of the Mughal Road system, establishing the Rupee as a standardised currency, and the unification of the country.[7] Prior to deindustrialisation, India was one of the largest economies in the world, accounting for approximately one quarter of the global economy. Mughal India is considered to be one of the richest periods among early modern Islamic cultures.[8] The Indian economy specialised in industrialisation and manufacturing, accounting for at least one quarter of the world's manufacturing output before the 18th century.[9]

Under the Mughal Empire, agricultural production had increased particularly food crops such as barley, rice and wheat and other non-food crops such as opium and cotton. By the middle of the 17th century, India had begun to grow large amounts of foreign crops including maize and tobacco.[10]

The downfall of Mughal Empire also led to the problems of aggregate supply for Indian manufactured goods. Other explanations for causes include the revolution in world transport and productivity gains by Britain from cottage production to factory goods resulted in uneconomic production in India. This resulted in Britain initially gaining control over export market and then domestic market as well.[2] Therefore, India experienced the phase of deindustrialisation after 1810 because of favour in terms of trade shocks and free commitment of trade between the trading patterns for colonial rulers.

Company rule (1757-1858)

The Company Rule in India refers to areas in the Indian subcontinent which were under the rule of British East Indian Company. The East Indian Company began its rule over the Indian subcontinent starting with the Battle of Plessey, which ultimately led to the vanquishing of the Bengal Subah and the founding of the Bengal Presidency in 1765, one of the largest subdivisions of British India.[11]

Capital amassed from Bengal following the Battle of Plessey assisted in investment in textile manufacturing during textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution,[12] increasing the wealth of the British [13] and ultimately contributing to deindustrialisation in Bengal. Furthermore, under Company rule, large Indian markets were exposed to British goods which were sold in India without any forms of protection while local Indian producers were heavily taxed. Protectionist policies were set up by the British empire to restrict the sale of Indian good and services overseas although raw materials used in textile manufacturing such as cotton were imported to Britain factories and worked.[14] These manufactured textiles were resold by the British in India and eventually led to the British Industrial Revolution, resulting in Britain overtaking India as the largest cotton textile manufacturer in the world by the 19th century.[15] Economic policies implemented by Britain allowed for a monopoly over India's large market and cotton resources and turned India into a captive market for Britain.[16]

Following the annexation of Oudh under British rule in 1856, all of the Indian subcontinent up to the Himalayas and most of Burma was ruled by the Company or local rulers which were allied with the Company at the tie.[17] During the Company rule period, the British East Indian Company had established four main headquarters across the Indian subcontinent. The major British territories across the Indian subcontinent included the Bengal Presidency, Bombay Presidency, Madras Presidency and the North-Western Provinces.[18]

The Company rule and the expansion of the British East India Company continued up until the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Ultimately, the Company rule ended with the Government of India Act 1858 following the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857,[19] although the British East India Company was formally dissolved by Act of Parliament in 1874.[17]

Cause of de-industrialisation in India

In the period between 1775 and 1800, significant innovations occurred in the British cotton industry which increased their total output and the cost of the production declined. This created significant challenges for cotton producers in India where prices were high. During the same time period, the influence of the British empire increased in the eastern hemisphere as did their control over the Indian sub-continent. British colonial rulers of India considered the need for increasing the market for British produced cotton.[3] British cotton was often produced in surplus quantity by using sophisticated machinery and was exported to the British colonies where it faced competition from indigenous cotton producers. The prices of the British cotton industry were reduced to significantly increase the dominance of British cotton, and unfair taxes were imposed on local producers.[20][21] This led to a decline in the indigenous cotton industry of the colonies and the domestic activities associated with the production of Indian cotton fell. The fall of the Indian cotton industry is one of the important factors behind the decline of Indian GDP under British rule. The standard of living in Britain increased from the middle of the seventeenth century and in the same period, the standard of living in India decreased significantly. During the 1700s, Indian GDP was 60 percent of British GDP and by the end of the 19th century it decreased to less than 15 percent in comparison.[22]

The fall in the hegemony of Mughals reduced the overall productivity of agriculture and reduced the supply of grains.[2] The grain was the primary consumption good for the Indian workers and was non-tradeable. The reduction in the supply of grain resulted in the rise of its prices. This rise in prices and negative supply shock led to a rise in the nominal wages in the cotton and weaving industry. The increased competition from British cotton and rising nominal wages reduced the profitability of the cotton industry of India. Thus, the negative supply shock in agricultural production is also an important reason behind the de-industrialisation of cotton–industries.

The short run as well as long run impact on living standards and growth rate of GDP providing agriculture sector competitive advantage with strengthening of the productivity advance on the land at home or increasing openness to world in turn increases GDP in the short run.[2] The causes of de-industrialisation are region or country specific as in the case of India in the 19th and 20th century. The colonial rule under the British led to the decline of textile and handicrafts industries through their policies and introduction of machine made goods in to the Indian market. Some of the causes of de-industrialisation in India during that period were:

- Introduction of machine made goods in the Indian subcontinent at a cheaper rate, which led to the decline of the traditional textile industry of India.

- Tariff policy opted by the British led to the decline of the handicraft industry, the British government started using preferential trade policies under which British goods were entering in India duty free or no nominal duty payment while Indian exporters had to pay high duty to export goods to British Mainland. Local producers were also subject to a tax (3-10%) to put them on equal footing with British imports that were subject to a tax of the same magnitude.[20]

- Internal Causes, as there were no efforts made to explore products for the Indian markets, the international trade market was in the control of international traders, the manually skilled laborers and traders associated with it were at the pity of the international trade merchants as far as supply or demand propagation in international trade markets was concerned. The guilds or craftsmen organization was also definitely very weak in India as compared to other nations.

- Changes in social conditions that resulted in consistent decline in manufacturing employment that requires access to raw materials and natural resources.[2]

- British rule establishment also resulted in the loss of powers of the craftsmen organization and other bodies that used to supervise and regulate the trade, which results in the fall down of raw materials as well as the skilled laborers which further results in the decline of market value of the products.

- The abolition of court culture and urban aristocrats resulted in decreased demand for these handicrafts as product demand for these dried up.

Rule under the British Raj (1858-1947)

The rule of the Indian economy under the British Raj refers to the period of the British's direct imperial rule over India from 1858 to 1947, which mainly arose due to revolt against the Company rule by Indians. This marked the formal conquest of India by the British.[3]

Under rule of the British Raj, the Indian economy was in a state of stagflation and further deindustrialisation while the British economy went through the Industrial Revolution.[23] Several economic policies implemented by the British Raj also caused a severe decrease in Indian handicraft (and handiloom) sectors of the economy, particularly resulting in a large decrease in demand for employees, goods and services.[24] Although the Raj did not provide capital to the British economy, due to Britain's declining position in the steel making industry in comparison to the US and Germany, the Raj had steel mills set up in India.[25] The Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) first operated in Bihar in 1908 and later became the largest and leading steel producer in India in 1945.[26]

Large amounts of investments by the private and public British investors contributed to a revamped railway system in India, mainly being used for economic growth and military use. This led to the creation of the fourth largest railway system in the world.[27] At first however, the initial use of the railway system was by private British companies. In 1837, the first train used on the railway system for freight transport ran from Red Hills to Chintadripet bridge in Madras.[28] In 1853, the railway began to be used for passenger travel services from Bombay to Thane, eventually expanding throughout most of the Indian subcontinent. During the First World War, the trains were used to transport troops and grain to other countries such as Britain and South Africa, although by the end of the war, the railway system was largely deteriorated.[28]

During the Great Depression, the Indian economy was not significantly impacted and the government was mainly focused on the shipping of gold to Britain.[29] The most significant economic impact on the Indian economy was deflation, which directly impacted the debt of villagers, and overseas trading of jute in Bengal, a key trading element through the 1920s which had significantly decline during the early 1930s. Furthermore, declining prices of jute and other food crops severely impacted large scale farmers in India. In contrast, sugar became a largely traded crop and a successful industry in the early 1930s.[30]

Impact of de-industrialisation in India

The effect of de-industrialisation on the Indian subcontinent is difficult to observe before 1810.[2] The factory driven technologies for the production of cotton appeared between 1780 and 1820, but, India started to lose its dominant position as the exporter of cotton before this period due to low wages in the Indian cotton industry. It also acted as a catalyst in migrating work force from cotton industry to Indian grain industry. The production capacity of the Indian cotton industry started to decline due to the prevailing wage rate. Furthermore, Indian de-industrialisation is also hard to track due to its relatively low share of textile exports in the total textile production.

In India, by 1920, the trade to GDP ratio declined and international trade reshaped the domestic structure of the economy.[31] India became one of the major markets for the British made cotton yarns and cloths and became one of the large suppliers of Grain. The price of cotton decreased by more than a third in the 1900s as compared to the level in 1800.[31] The fall in prices of cotton significantly reduced the production of Indian hand spinning industry which is considered to be the most important specimen of de-industrialisation in India. The industrial revolution of the British cotton industry resulted in the globalization of its colonies as a mean to export excess production. This resulted in the fall the production of cotton in the indigenous industries of colonies due to low prices of British cotton and its derived products.

The large scale de-industrialisation brought far reaching impacts on the economy with loss to traditional economy, which was earlier considered as a blend of agriculture and handicrafts. Spinning and weaving functioned as subsidiary industries in the old economy resulted in differences to the interior equilibrium of the rural market. As an outcome, this led to manually skilled labourers shifting back to agricultural productivity and such overcrowding decreased the efficiency of agriculture sector as well. Land holding fragmentation, excessive cultivation and low-grade and infertile land utilization are the straight impacts of the same. It created a large base of underemployed and disguised rural unemployed. The number of workers engaged in agriculture sector increased from 7.17 crores to 10.02 crores in 1931 and industrial employed workers decreased from 2.11 crores to 1.29 crores during the same period.[32]

The de-industrialisation of India played an important role in the underdevelopment and increasing poverty in the country. The British-led globalisation of Colonial India led to the significant inflow of British cotton which led to falling in the output of the domestically produced cotton due to low prices. Consequently, the de-industrialisation process increased the unemployment of artisan and employees of indigenous cotton industry of India. The unemployed artisans and employees resorted to agriculture and it also contributed to the regression towards agriculture and resulted in the surplus labour of land.[31] The colonial policies associated with the land and taxation undermined ability of the peasant class to control and command the land. It pushed these peasants to take significant debt from non-cultivating moneylenders who charged significantly high interests and aided in the underdevelopment and poverty.

Aftermath

India became independent from the rule of the British Raj on 15 August 1947.[33]

India had undergone socialist reforms from the 1950s to 1990s. Prior to economic liberalisation, India experienced low rates of annual economic growth known as the "Nehruvian Socialist rate of growth" and low rates of per capita income growth.[34]

Numerous steel plants were set up in the 1950s by prime minister Nehru under the belief that India had needed to maximise steel production in order for the economy to succeed. This led to the formation of Hindustan Steel Limited (HSL), a government owned company and the establishment of three steel plants throughout the India during the 1950s.[35]

In 1991, the Indian economy underwent economic liberalisation. Through which, India transitioned to a more service and market based sector, with particular emphasis on expanding foreign and private investment within India. Furthermore, in response to deindustrialisation, liberalisation included reductions in import tariffs and taxes, as well as ending many Public Monopolies.[36] Majority of the changes were implemented as a condition for a $500 million loan by the IMF and World Bank to bail out India's government in December 1991.[37]

By the end of the 20th century, India had transitioned towards a free-market economy, through which there was a major decline of state control over India's economy and increased financial liberalisation.[38]

Economic data

Prior to deindustrialisation, the Indian economy accounted for roughly 25% of the global economy.[39] Economic data collected by the OECD shows that growth during the Mughal Empire's reign was more than twice faster than it was around five hundred years prior to the Mughal era.[40] Under the British Raj rule, from 1880 to 1920, the Indian economy's GDP growth rate and population growth rate increased at approximately 1%.[41]

Following deindustrialisation, India's share of the global economy had dropped to approximately 4% in the 1950s.[42]

India's annual growth rate remained approximately around 3.5% prior to economic liberalisation. Per capita income growth had averaged around 1.3% per year.[34]

India's GDP growth rate slowly increased to 7% in the 2018-19 period.[43]

During 2018, India became the fastest emerging economy in the world. India is predicted to return as one of the three largest economies in the world by 2034.[43]

By 2025, it is expected that the Indian working age population will account for at least one quarter of the world economy's working age population.[21]

By 2035, the five largest cities in India are expected to have economies similar in size to middle income economies.[21]

Conclusion of de-industrialisation in India

Amiya Bagchi considers the economic growth rate to have been insufficient to offset the trajectory of de-industrialisation, stating: "Thus the process of de-industrialisation proved to be a process of pure immoderation for the several million persons...[3]"

See also

Reference lists

- ↑ Rowthorn, R; Ramaswamy, R (1997). "Economic Issues 10—Deindustrialisation—Its Causes and Implications". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clingingsmith, David; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (July 2008). "Deindustrialisation in 18th and 19th Century India: Mughal Decline, Climate Shocks and British Industrial Ascent". Explorations in Economic History. 45 (3): 209–234. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2007.11.002.

- 1 2 3 4 Bagchi, Amiya Kumar (1976). "De‐industrialisation in India in the nineteenth century: Some theoretical implications". The Journal of Development Studies. 12 (2): 135–164. doi:10.1080/00220387608421565. ISSN 0022-0388.

- ↑ Sarkar, Prabirjit (1992). "De-industrialisation Through Colonial Trade". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 22 (3): 297–302. doi:10.1080/00472339280000211. ISSN 0047-2336. S2CID 153913617.

- ↑ Baines, Edward (1835). History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain. London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher, and P. Jackson. OCLC 1070976855.

- 1 2 Broadberry, Stephen; Custodis, Johann; Gupta, Bishnupriya (January 2015). "India and the Great Divergence: An Anglo-Indian Comparison of GDP per Capita, 1600–1871". Explorations in Economic History. 55: 58–75. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2014.04.003. S2CID 130940341.

- ↑ Richards, John F., (2012) (1993), "The economy, societal change, and international trade", The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–204, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511584060.012, ISBN 9780511584060

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Freitag, Sandria B.; Bayly, C. A. (1991). "The Raj: India and the British 1600-1947". The Journal of Asian Studies. 50 (3): 713. doi:10.2307/2057621. JSTOR 2057621. S2CID 161490128.

- ↑ Clingingsmith, David; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (2008). "Deindustrialization in 18th and 19th century India: Mughal decline, climate shocks and British industrial ascent". Explorations in Economic History. 45 (3): 209–234. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2007.11.002. ISSN 0014-4983.

- ↑ Schmidt, Karl J. (2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. doi:10.4324/9781315706429. ISBN 9781315706429.

- ↑ Simmons, Colin (1987). "The Great Depression and Indian Industry: Changing Interpretations and Changing Perceptions". Modern Asian Studies. 21 (3): 585–623. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00009215. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 312643. S2CID 145538790.

- ↑ Esposito, John L. (2004). The Islamic world : past and present. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195165203. OCLC 52979240.

- ↑ Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. ISBN 9781136825521.

- ↑ Jonathan P. Eacott (2012). "Making an Imperial Compromise: The Calico Acts, the Atlantic Colonies, and the Structure of the British Empire". The William and Mary Quarterly. 69 (4): 731–762. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.69.4.0731. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.69.4.0731.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2009). "Lancashire, India, and shifting competitive advantage in cotton textiles, 1700-1850: the neglected role of factor prices". The Economic History Review. 62 (2): 279–305. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2008.00438.x. ISSN 0013-0117. S2CID 54975143.

- ↑ Yule, Henry (13 June 2013). Hobson-jobson : the definitive glossary of British India. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199601134. OCLC 877513576.

- 1 2 "East India Company and Raj 1785-1858". UK Parliament. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Clarendon Press. 1908–1931. OCLC 48172249.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II (1908), The Indian Empire, Historical, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxxv, 1 map, 573, pp. 488–514

- 1 2 Bairoch, Paul (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-226-03463-8.

- 1 2 3 "Overview - An India Economic Strategy To 2035 - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". dfat.gov.au. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen; Custodis, Johann; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2015). "India and the great divergence: An Anglo-Indian comparison of GDP per capita, 1600–1871". Explorations in Economic History. 55: 58–75. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2014.04.003. S2CID 130940341.

- ↑ Cypher, James M. (24 April 2014). The process of economic development (Fourth ed.). London. ISBN 9781136168284. OCLC 879025667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Raychaudhuri, Tapan; Habib, Irfan, eds. (2005). The Cambridge economic history of India (Expanded ed.). New Delhi: Orient Longman in association with Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-8125027102. OCLC 64451735.

- ↑ Bahl, Vinay (1994). "The emergence of large-scale steel industry in India under British colonial rule, 1880-1907". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 31 (4): 413–460. doi:10.1177/001946469403100401. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 144471617.

- ↑ Nomura, Chikayoshi (2011). "Selling steel in the 1920s: TISCO in a period of transition". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 48 (1): 83–116. doi:10.1177/001946461004800104. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 154594018.

- ↑ Kerr, Ian J. (2007). Engines of change : the railroads that made India. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 9780313046124. OCLC 230808683.

- 1 2 Bhandari, R. R. (2005). Indian railways : glorious 150 years. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Govt. of India. ISBN 978-8123012544. OCLC 61513410.

- ↑ "Front Matter", China During the Great Depression, Harvard University Asia Center, 2008, pp. i–x, doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5pkv.1, ISBN 9781684174652

- ↑ Tomlinson, B.R. (1975). "India and the British Empire, 1880-1935". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 12 (4): 337–380. doi:10.1177/001946467501200401. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 144217855.

- 1 2 3 Roy, Tirthankar (2007). "Globalisation, Factor Prices, and Poverty in Colonial India". Australian Economic History Review. 47 (1): 73–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8446.2006.00197.x. ISSN 0004-8992.

- ↑ "De-Industrialisation in India: Process, Causes and Effects | Indian Economic History". History Discussion - Discuss Anything About History. 4 November 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ↑ Office, Public Record (2009). "Learning Curve British Empire". Public Record Office, The National Archives. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- 1 2 "Redefining The Hindu Rate Of Growth". The Financial Express. 12 April 2004. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Ghose, Sankar (1993). Jawaharlal Nehru, a biography. New Delhi: Allied Publishers. p. 550. ISBN 978-8170233695. OCLC 30701738.

- ↑ "The World Economy in Transition", World Development Report 1991, The World Bank, 30 June 1991, pp. 12–30, doi:10.1596/9780195208689_chapter1, ISBN 9780195208689

- ↑ Timor-Leste Economic Report, October 2018 (PDF). World Bank. 2018. doi:10.1596/30998. S2CID 240122138.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, C. P.; Pal, Parthapratim (2006). "Financial Liberalisation in India: An Assessment of Its Nature and Outcomes". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (11): 975–988. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4417962.

- ↑ Moosvi, Shireen (2015) [First published 1989]. The economy of the Mughal Empire, c.1595 : a statistical study (2nd ed.). New Delhi, India. ISBN 978-0-19-908549-1. OCLC 933537936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy. Paris, France: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. ISBN 9789264022621. OCLC 85776699.

- ↑ Tomlinson, Brian Roger (1993). The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970, New Cambridge history of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. Volume III, 3, Cambridge University Press, p. 109. ISBN 978-0-521-36230-6.

- ↑ Maddison, Angus (2003). The world economy : historical statistics. Paris, France: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. ISBN 978-9264104129. OCLC 326529006.

- 1 2 "Indian Economy: Overview, Market Size, Growth, Development, Statistics...IBEF". www.ibef.org. Retrieved 14 May 2019.