National Society Daughters of the American Revolution | |

DAR Constitution Hall, Washington, DC patriotism | |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C., United States |

|---|---|

| Publication | American Spirit Magazine, Daughters Magazine |

| Affiliations | Children of the American Revolution |

| Website | dar.org |

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' struggle for independence.[1] A non-profit group, they promote education and patriotism. The organization's membership is limited to direct lineal descendants of soldiers or others of the Revolutionary period who aided the cause of independence; applicants must have reached 18 years of age and have a birth certificate indicating gender as female. The DAR has over 190,000 current members[2] in the United States and other countries.[3] Its motto is "God, Home, and Country".[4][5][6]

Founding

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1889, the centennial of President George Washington's inauguration was celebrated, and Americans looked for additional ways to recognize their past. Out of the renewed interest in United States history, numerous patriotic and preservation societies were founded. On July 13, 1890, after the Sons of the American Revolution refused to allow women to join their group, Mary Smith Lockwood published the story of patriot Hannah White Arnett in The Washington Post, asking, "Where will the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution place Hannah Arnett?"[7] On July 21 of that year, William O. McDowell, a great-grandson of Hannah White Arnett, published an article in The Washington Post offering to help form a society to be known as the Daughters of the American Revolution.[7] The first meeting of the society was held August 9, 1890.[7]

The first DAR chapter was organized on October 11, 1890,[8] at the Strathmore Arms, the home of Mary Smith Lockwood, one of the DAR's four co-founders. Other founders were Eugenia Washington, a great-grandniece of George Washington, Ellen Hardin Walworth, and Mary Desha. They had also held organizational meetings in August 1890.[9] Other attendees in October were Sons of the American Revolution members Registrar General Dr. George Brown Goode, Secretary General A. Howard Clark, William O. McDowell (SAR member #1), Wilson L. Gill (secretary at the inaugural meeting), and 18 other people.

The First Lady, Caroline Lavina Scott Harrison, wife of President Benjamin Harrison, lent her prestige to the founding of DAR, and served as its first President General. Having initiated a renovation of the White House, she was interested in historic preservation. She helped establish the goals of DAR, which was incorporated by congressional charter in 1896.

In this same period, such organizations as the Colonial Dames of America, the Mary Washington Memorial Society, Preservation of the Virginia Antiquities, United Daughters of the Confederacy, and Sons of Confederate Veterans were also founded. This was in addition to numerous fraternal and civic organizations flourishing in this period.

Structure

The DAR is structured into three Society levels: National Society, State Society, and Chapter. A State Society may be formed in any US State, the District of Columbia, or other countries that are home to at least one DAR Chapter. Chapters can be organized by a minimum of 12 members, or prospective members, who live in the same city or town.[10]

Each Society or Chapter is overseen by an executive board composed of a variety of officers. National level officers are: President General, First Vice President General, Chaplain General, Recording Secretary General, Corresponding Secretary General, Organizing Secretary General, Treasurer General, Registrar General, Historian General, Librarian General, Curator General, and Reporter General, to be designated as Executive Officers, and twenty-one Vice Presidents General. These officers are mirrored at the State and Chapter level, with a few changes: instead of a President General, States and Chapters have Regents, the twenty-one Vice Presidents General become one Second Vice Regent position, and the title of "General" is replaced by the title of either "State" or "Chapter". Example: First Vice President General becomes State First Vice Regent.[11]

Historic programs

The DAR chapters raised funds to initiate a number of historic preservation and patriotic endeavors. They began a practice of installing markers at the graves of Revolutionary War veterans to indicate their service, and adding small flags at their gravesites on Memorial Day.

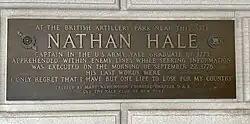

Other activities included commissioning and installing monuments to battles and other sites related to the War. The DAR recognized women patriots' contributions as well as those of soldiers. For instance, they installed a monument at the site of a spring where Polly Hawkins Craig and other women got water to use against flaming arrows, in the defense of Bryan Station (present-day Lexington, Kentucky).

In addition to installing markers and monuments, DAR chapters have purchased, preserved, and operated historic houses and other sites associated with the war.

DAR Hospital Corps (Spanish–American War, 1898)

In the 19th century, the U.S. military did not have an affiliated group of nurses to treat servicemembers during wartime. At the onset of the Spanish–American War in 1898, the U.S. Army appointed Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee as Acting Assistant Surgeon to select educated and experienced nurses to work for the Army. As Vice President of the DAR (who also served as NSDAR's first Librarian General), Dr. McGee founded the DAR Hospital Corps to vet applicants for nursing positions. The DAR Hospital Corps certified 1,081 nurses for service during the Spanish–American War. DAR later funded pensions for many of these nurses who did not qualify for government pensions. Some of the DAR-certified nurses were trained by the American Red Cross, and many others came from religious orders such as the Sisters of Charity, Sisters of Mercy, and Sisters of the Holy Cross.[12][13] These nurses served the U.S. Army not only in the United States but also in Cuba and the Philippines during the war. They paved the way for the eventual establishment—with Dr. McGee's assistance—of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901.[14]

Textbook committees

During the 1950s, statewide chapters of the DAR took an interest in reviewing school textbooks for their own standards of suitability. In Texas, the statewide "Committee on Investigations of Textbooks" issued a report in 1955 identifying 59 textbooks currently in Texas public schools that had "socialistic slant" or "other deficiencies" including references to "Soviet Russia" in the Encyclopedia Britannica.[15] In 1959, the Mississippi chapter's "National Defense Committee" undertook a state lobbying effort that secured an amendment to state law which added "lay" members to the committee reviewing school textbooks. A DAR board member was appointed to one of the seats.[16]

Contemporary DAR

There are nearly 180,000 current members of the DAR in approximately 3,000 chapters across the United States and in several other countries. The organization describes itself as "one of the most inclusive genealogical societies"[17] in the United States, noting on its website that, "any woman 18 years or older — regardless of race, religion, or ethnic background — who can prove lineal descent from a patriot of the American Revolution, is eligible for membership".[17] The current DAR President General is Pamela Rouse Wright, the founder and owner of a jewelry and luxury goods business in Texas.

Eligibility

Membership in the DAR today is open to all women, regardless of race or religion, who can prove lineal bloodline descent from an ancestor who aided in achieving United States independence.[1] The National Society DAR is the final arbiter of the acceptability of the documentation of all applications for membership.

Qualifying participants in achieving independence include the following:

- Signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence;

- Military veterans of the American Revolutionary War, including State navies and militias, local militias, privateers, and French or Spanish soldiers and sailors who fought in the American theater of war to include the Island of Cuba;

- Civil servants of provisional or State governments, Continental Congress and State conventions and assemblies;

- Signers of Oath of Allegiance or Oath of Fidelity and Support;

- Participants in the Boston Tea Party or Edenton Tea Party;[18]

- Prisoners of war, refugees, and defenders of fortresses and frontiers; doctors and nurses who aided Revolutionary casualties; ministers; petitioners; and

- Others who gave material or patriotic support to the Revolutionary cause.[1]

The DAR published a book, available online,[19] with the names of thousands of minority patriots, to enable family and historical research. Its online Genealogical Research System (GRS)[20] provides access to a database, and it is digitizing family Bibles to collect more information for research.

The organization has chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in the District of Columbia. DAR chapters have been founded in Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bermuda, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The DAR is a governing organization within the Hereditary Society Community of the United States of America, and each DAR President General has served on HSC's board since its inception.

In June 2023, at the 132nd DAR Continental Congress, the organization voted to add an amendment to their bylaws that states the chapters "may not discriminate against an eligible applicant based on race, religion, sexual orientation, national origin, age, disability, or any other characteristic protected by applicable law." DAR spokesperson Bren Landon told Newsweek that the amendment "provides additional non-discrimination language" that protects the society's tax-exempt status. She also told Newsweek that "the new language does not change the criteria for membership," and that "DAR's longstanding membership policy remains unchanged since our founding in 1890."[21] At the congress, Jennifer Mease, a delegate and Regent of the Liberty Bell Chapter in Pennsylvania, inquired whether chapters could vote against admitting transgender women on the basis of their sex even if they had changed their birth certificates to match their preferred gender identity.[21] President General Wright responded to Mease's inquiry by stating "if a person’s certified birth certificate states ‘female,’ they are eligible for membership, and your chapter cannot change that.. if their birth certificate says they are a female, and you vote against them based on their protected class, it's discrimination."[21] In an official newsletter released after the congress, Wright wrote, "some have asked if this means a transgender woman can join DAR or if this means that DAR chapters have previously welcomed transgender women. The answer to both questions is, yes."[22]

Education outreach

The DAR contributes more than $1 million annually to support five schools that provide for a variety of special student needs.[23] Supported schools:

- Kate Duncan Smith DAR School, Grant, Alabama

- Crossnore School, Crossnore, North Carolina

- Hillside School, Marlborough, Massachusetts

- Hindman Settlement School, Hindman, Kentucky

- Berry College, Mount Berry, Georgia

In addition, the DAR provides $70,000 to $100,000 in scholarships and funds to American Indian youth at Chemawa Indian School, Salem, Oregon; Bacone College, Muskogee, Oklahoma; and the Indian Youth of America Summer Camp Program.[24]

Civic work

DAR members participate in a variety of veteran and citizenship-oriented projects, including:

- Providing more than 200,000 hours of volunteer time annually to veterans in U.S. Veterans Administration hospitals and non-VA facilities

- Offering support to America's service personnel in current conflicts abroad through care packages, phone cards and other needed items

- Sponsoring special programs promoting the Constitution during its official celebration week of September 17–23

- Participating in naturalization ceremonies

Exhibits and library at DAR Headquarters

The DAR maintains a genealogical library at its headquarters in Washington, DC, and provides guides for individuals doing family research. Its bookstore presents scholarship on United States and women's history.

Temporary exhibits in the galleries have featured women's arts and crafts, including items from the DAR's quilt and embroidery collections. Exhibit curators provide a social and historical context for girls' and women's arts in such exhibits, for instance, explaining practices of mourning reflected in certain kinds of embroidery samplers, as well as ideals expressed about the new republic. Permanent exhibits include American furniture, silver and furnishings.

Literacy promotion

In 1989, the DAR established the NSDAR Literacy Promotion Committee, which coordinates the efforts of DAR volunteers to promote child and adult literacy. Volunteers teach English, tutor reading, prepare students for GED examinations, raise funds for literacy programs, and participate in many other ways.[25]

American history essay contest

Each year, the DAR conducts a national American history essay contest among students in grades 5 through 8. A different topic is selected each year. Essays are judged "for historical accuracy, adherence to topic, organization of materials, interest, originality, spelling, grammar, punctuation, and neatness." The contest is conducted locally by the DAR chapters. Chapter winners compete against each other by region and nationally; national winners receive a monetary award.[26]

Scholarships

The DAR awards $150,000 per year in scholarships to high school graduates, and music, law, nursing, and medical school students. Only two of the 20 scholarships offered are restricted to DAR members or their descendants.[27]

African Americans and the DAR

In 1932 the DAR adopted a rule excluding African American musicians from performing at DAR Constitution Hall in response to complaints by some members against "mixed seating," as both black and white people were attracted to concerts of black artists. In 1939, they denied permission for Marian Anderson to perform a concert. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a DAR member, resigned from the organization. In her letter to the DAR, Roosevelt wrote, "I am in complete disagreement with the attitude taken in refusing Constitution Hall to a great artist... You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way and it seems to me that your organization has failed." Author Zora Neale Hurston, however, criticized Roosevelt's refusal to condemn the Board of Education of D.C.'s simultaneous decision to exclude Anderson from singing at the segregated white Central High School. Hurston declared “to jump the people responsible for racial bias would be to accuse and expose the accusers themselves. The District of Columbia has no home rule; it is controlled by congressional committees, and Congress at the time was overwhelmingly Democratic. It was controlled by the very people who were screaming so loudly against the DAR. To my way of thinking, both places should have been denounced, or neither.” [28]

As the controversy grew, the American press overwhelmingly backed Anderson's right to sing. The Philadelphia Tribune wrote, "A group of tottering old ladies, who don't know the difference between patriotism and putridism, have compelled the gracious First Lady to apologize for their national rudeness." The Richmond Times-Dispatch wrote, "In these days of racial intolerance so crudely expressed in the Third Reich, an action such as the D.A.R.'s ban ... seems all the more deplorable." At Eleanor Roosevelt's behest, President Roosevelt and Walter White, then-executive secretary of the NAACP, and Anderson's manager, impresario Sol Hurok arranged an open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with a dignified and stirring rendition of "America (My Country, 'Tis of Thee)". The event attracted a crowd of more than 75,000 in addition to a national radio audience of millions.[29]

The DAR officially reversed its "white performers only" policy in 1952.[30] However, in 1957, the Colorado branch of the DAR refused to allow a Mexican American child to participate in an Abraham Lincoln birthday event.[31]

In 1977, Karen Batchelor Farmer (now Karen Batchelor) of Detroit, Michigan, was admitted to the Ezra Parker Chapter (Royal Oak, MI) as the first known African American member of the DAR.[32] Batchelor's admission as the first known African American member of DAR sparked international interest after it was featured in a story on page one of The New York Times.[33] In 1984, Lena Lorraine Santos Ferguson, a retired school secretary, was denied membership in a Washington, D.C. chapter of the DAR because she was Black, according to a report by The Washington Post.[34] Ferguson met the lineage requirements and could trace her ancestry to Jonah Gay, a white man who fought in Maine.[34] When asked for comment, Sarah M. King, the President General of the DAR, told The Washington Post that the DAR's chapters have autonomy in determining members.[34] King went on to tell Washington Post reporter Ronald Kessler, "Being black is not the only reason why some people have not been accepted into chapters. There are other reasons: divorce, spite, neighbors' dislike. I would say being black is very far down the line....There are a lot of people who are troublemakers. You wouldn't want them in there because they could cause some problems."[34] After King's comments were reported in a page one story, outrage erupted, and the D.C. City Council threatened to revoke the DAR's real estate tax exemption. King quickly corrected her error, saying that Ferguson should have been admitted, and that her application had been handled "inappropriately". DAR changed its bylaws to bar discrimination "on the basis of race or creed." In addition, King announced a resolution to recognize "the heroic contributions of black patriots in the American Revolution."[35]

Since the mid-1980s, the DAR has supported a project to identify African Americans, Native Americans, and individuals of mixed race who were patriots of the American Revolution, expanding their recognition beyond soldiers.[36] In 2008, DAR published Forgotten Patriots: African-American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War.[19][36] In 2007, the DAR posthumously honored one of Thomas Jefferson's slaves, Mary Hemings Bell, as a "Patriot of the Revolution." Because of Hemings Bell's declaration by the DAR to be a Patriot, all of her female descendants qualify for membership in the DAR.[37] Wilhelmena Rhodes Kelly, in 2019, became the first African American elected to the DAR National Board of Management when she was installed as New York State Regent in June.[38]

Notable members

Living members

- Karen Batchelor, American lawyer and genealogist and the first African American member of the DAR

- Betsy Boze, American academic, chief executive officer and dean, Kent State University Stark[39]

- Ada E. Brown, first African American woman federal judge appointed by President Donald Trump and confirmed by the Senate, and first African American woman on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas in its 140-year history. Second Native American woman to become a federal judge

- Carol Burnett, American actress, comedian, singer, and writer

- Laura Bush, former First Lady of the United States[40]

- Bo Derek, actress, former model, and veterans advocate[40]

- Elizabeth Dole, former U.S. Senator from North Carolina, former transportation secretary, labor secretary, American Red Cross president, Federal Trade Commissioner, presidential candidate, and presidential advisor[40]

- Tammy Duckworth, American Army veteran, former U.S. Representative, and from 2017, U.S. Senator from Illinois. Duckworth is depicted along with Molly Pitcher in a statue sponsored by the DAR Illinois chapter and dedicated to women veterans on the grounds of the Brehm Memorial Library in Mt. Vernon, Illinois[41]

- Candace Whittemore Lovely, painter

- Dr. Donna J. Nelson, chemistry professor

- Katie Pavlich, conservative commentator, author, blogger, and podcaster

- Margaret Rhea Seddon, NASA astronaut[40]

- Wilma Vaught, American military officer and first woman to reach the rank of brigadier general from the comptroller field

Deceased members

- Jane Addams, activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner[40]

- Mary Jane Aldrich (1833–1909), American temperance reformer and lecturer

- Susan B. Anthony, American suffragist[40]

- Lillie Stella Acer Ballagh, national chairman of Colonial Relics[42]

- Mary Ross Banks (1846–1910), litterateur and author

- Clara Barton, American Red Cross founder[40]

- Octavia Williams Bates (1846–1911), suffragist, clubwoman, author

- Jennie Iowa Berry (1866-1951), National President, Woman's Relief Corps

- Frances E. Burns (1866–1937), social leader, business executive

- Mary Temple Bayard (1853–1916), American writer, journalist[43]

- Cora M. Beach, State Chairman and member of National Committee for Genealogical and Historical Research[42]

- Clara Bancroft Beatley (1858–1923), educator, lecturer, author[44]

- Fanny Yarborough Bickett (1870-1941), First Lady of North Carolina and first female president of the North Carolina Railroad

- Ella A. Bigelow (1849–1917), author and clubwoman[45]

- Rosalynn Carter, former First Lady of the United States, politician, political and social activist[40]

- Sarah Bond Hanley, first Democratic woman to serve in the Illinois House of Representatives. She served as the Illinois State Regent.[46][47]

- Leah Belle Kepner Boyce, State Recording and Secretary of the California Daughters of the American Revolution[42]

- Gene Bradford (1909–1937), member of the Washington State House of Representatives

- Alice Willson Broughton (1889–1980), First Lady of North Carolina[48]

- Olivia Dudley Bucknam, Hollywood chapter[42]

- Eleanor Kearny Carr (1840–1912), First Lady of North Carolina[49]

- Luella J. B. Case (1807–1857), author

- Marietta Stanley Case (1845–1900), poet and temperance advocate

- Mildred Stafford Cherry (1894–1971), First Lady of North Carolina

- Annetta R. Chipp (1866–1961), temperance leader and prison evangelist[50]

- Florence Anderson Clark (1835–1918), author, newspaper editor, librarian, university dean

- Vinnie B. Clark, established and developed the Geography Department at the San Diego State Teachers College[42]

- Clara Rankin Coblentz (1863–1933), social reformer

- Sarah Johnson Cocke (1865–1944), writer and civic leader[51]

- Margaret Wootten Collier (1869–1947), author[52]

- Emily Parmely Collins (1814–1909) – suffragist, activist, writer[53]

- Lura Harris Craighead (1858-1926) - author, parliamentarian, clubwoman

- Harriet L. Cramer (1847–1922) – newspaper publisher

- Inez Mabel Crawford, first registrar of the General Edward Hand Chapter[42]

- Belle Caldwell Culbertson (1857–1934), author and philanthropist

- Carrie Chase Davis (1863–1953), American physician, suffragist

- Margaret B. Denning (1856–1935), missionary and temperance worker

- Allie Luse Dick (1859–1933), music teacher

- Estelle Skidmore Doremus, supporter of the New York Philharmonic

- Ella Loraine Dorsey (1853–1935), author, journalist, translator

- Fanny Murdaugh Downing (1831–1894), author and poet

- Saidie Orr Dunbar, Executive Secretary of the Oregon Tuberculosis Association[42]

- Caroline B. Eager, American philanthropist who worked mainly with the Igorot people of the Philippine Islands[42]

- Ida Horton East (1842–1915), philanthropist

- Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science church

- Mary Elvira Elliott (1851-1942), writer and lecturer

- Isabel H. Ellis, Rubidoux Chapter[42]

- Margaret Dye Ellis (1845–1925), social reformer and lobbyist

- Lelia Dromgold Emig (1872–1957), genealogist

- Infanta Eulalia of Spain, Spanish Infanta and author[54]

- Lena Santos Ferguson (1928–2004), secretary and second African American member of the DAR

- Laura Dayton Fessenden (1852–1924), author

- Inglis Fletcher, American writer[42]

- Mary Alice Fonda (1837–1897), American musician, linguist, author, critic

- Abigail Keasey Frankel, prominent club and civic worker of Portland. She was the first president of the Oregon Federation of Business and Professional Women[42]

- Agnes Moore Fryberger (1868–1939), music educator[55]

- Sarah E. Fuller (1838-1913), philanthropist and social leader

- Dale Pickett Gay, Wyoming clubwoman and one of the best known women of her time in the oil business[42]

- Wilma Anderson Gilman (1881–1971), concert pianist, music teacher, clubwoman[56]

- Lillian Gish, actress[40]

- Fannie Smith Goble, held several high offices in Daughters of the American Revolution organization[42]

- Isophene Goodin Bailhache, national vice chairman of Historic Spots, State Officer, Chapter Regent[42]

- Gene Grabeel, mathematician and cryptanalyst who founded the Venona project[57]

- Harriet A. Haas, attorney and member of Piedmont Board of Education[42]

- Inez M. Haring, American botanist[58]

- Ethel Hillyer Harris, author

- Sallie Foster Harshbarger, from 1920 to 1922, State Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution[42]

- Caroline Harrison, former First Lady of the United States[40]

- L. Isabel Heald, social leader and philanthropic worker

- Mary Hilliard Hinton, historian, painter, anti-suffragist, pro-racial segregation

- Emily Caroline Chandler Hodgin, temperance reformer

- Margaret Gardner Hoey, First Lady of North Carolina[59]

- Grace Hopper, Rear Admiral, USNR[40]

- Anna Morris Holstein[60] (1825–1900), Founder First Regent D.A.R. Valley Forge Chapter, Hosted 1891 DAR National Leadership visit to Valley Forge,[61] Prayer Desk Dedicated at VF Memorial Chapel in her honor,[62] Founder, Regent Centennial and Memorial Association,[63][64] Civil War Nurse, Author.[65]

- Harriet Lane Huntress (1860–1922), Deputy Superintendent Public Instruction in New Hampshire

- Mary Anna Jackson (1831–1915), wife of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

- Electa Amanda Wright Johnson (1938–1929), philanthropist, writer

- Rebecca Richardson Joslin (1846–1934), writer, lecturer, benefactor, clubwoman

- Jennie Murray Kemp (1858-1928), temperance leader and writer[66]

- Sara Beaumont Kennedy (1859–1920), writer and newspaper editor

- Mary Lewis Langworthy (1872–1949), teacher, writer, lecturer, and executive

- Harriet Nisbet Latta (1853-1910), Founding State Regent of North Carolina

- Nancy A. Leatherwood, national chairman of Historical and Literary Reciprocity Committee of the Daughters of the American Revolution[42]

- Colonel Westray Battle Long, Director of the Women's Army Corps

- Anne Bozeman Lyon (1860–1936), writer[67]

- Edith Bolte MacCracken, State Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution[42]

- Mary Stuart James MacMurphy (1846–1934), teacher, lecturer, clubwoman, and author

- Virginia Donaghe McClurg, member[42]

- Ruth Karr McKee, member[42]

- Moina Michael, educator and originator of Memorial Day Poppies[68]

- Anne Hazen McFarland, M.D., physician and medical journal editor

- Anita Newcomb McGee, founder of the Army Nurse Corps[40]

- Anne Rogers Minor, artist and DAR President General, 1920–1923[69]

- Fanny E. Minot (1847–1919), national president Woman's Relief Corps

- Bessie Morse, founder of The Morse School of Expression, St. Louis[70]

- Sara E. Morse, held positions in several organizations[42]

- Grandma Moses, folk artist[40]

- Alice Curtice Moyer[71]

- Emma Huntington Nason (1845–1921), poet, author, and musical composer

- Jacqueline Noel, leader in promoting the colonial history of the United States[42]

- Cornelia Alice Norris, socialite, genealogist, and founding regent of the Caswell-Nash Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

- Florence Sillers Ogden, columnist, conservative activist, and segregationist

- Elizabeth Fry Page (?–1943), author, editor

- Jane Marsh Parker (1836–1913), author, historian, clubwoman

- Fannie Brown Patrick, musician and leader in civic and social affairs[42]

- Alice Paul, American suffragist[40]

- Edith Allen Phelps, twice president of the Oklahoma Library Association, the first professional in the Library Science field in the Oklahoma City system[42]

- Sarah Childress Polk, First Lady of the United States

- Frances Porcher, officer of the Jefferson Chapter[71]

- Delia Lyman Porter (1858–1933), author, social reformer, clubwoman

- Adele Poston, pioneer in the field of psychiatric nursing[72]

- Ada E. Purpus, member[42]

- Emily Lee Sherwood Ragan, author, journalist

- Emma May Alexander Reinertsen (1853–1920), writer

- Janet Reno, former Attorney General of the United States[40]

- Hester Dorsey Richardson (1862–1933), author[73]

- Alice Mary Robertson, educator and public servant from Oklahoma, second woman to serve in the United States Congress

- Lelia P. Roby, regent, DAR; founder, Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic

- Emily Warren Roebling, engineer, known for her contribution to the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge

- Ginger Rogers, actress and dancer[40]

- Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady of the United States. She resigned her membership in protest of racism.

- Fannie Forbis Russel, one of the pioneer women of the state of Montana[42]

- Susan Augusta Pike Sanders, national president of the Woman's Relief Corps[74]

- Phyllis Schlafly, conservative political activist and writer[40]

- Julia Green Scott, DAR President General

- M. Elizabeth Shellabarger, Registered Nurse, army nurse overseas during World War I and director of American Red Cross Nursing Service in Albania and Montenegro[42]

- Jessamine Shumate, noted artist and cartographer

- Eva Munson Smith (1843–1915), composer, poet, author

- Lura Eugenie Brown Smith (1864–?), journalist, newspaper editor, author[75]

- Margaret Chase Smith, US Congresswoman and US Senator[40]

- Mary Bell Smith (1818–1894), educator and temperance leader[76]

- Helen Norton Stevens, Lady Stirling Chapter[42]

- Mary Ingram Stille (1854–1935), historian, journalist, and temperance reformer

- Lillian Carpenter Streeter (1854–1935), social reformer, clubwoman, author

- Vera Blanche Thomas, president of the Arizona State Nurses' Association from 1927 to 1928[42]

- Adaline Emerson Thompson (1859–1951), benefactor and educational leader[77]

- Martha L. Poland Thurston (1849–1898), vice-president of the national body; also social leader, philanthropist, writer

- Lydia H. Tilton (1839–1915), lyricist of "Old Glory", the D.A.R. national song[78][79]

- Lizabeth A. Turner (1829–1907), National President, Woman's Relief Corps

- Gertrude Vaile (1878–1954), social worker

- Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, sculptor, art patron and collector, and founder in 1931 of the Whitney Museum of American Art[80]

- Maryly Van Leer Peck, Founder of Guam Community College, first female president of a Florida Community College, first woman chemical engineer graduate from Vanderbilt University. Received the National Community Service Award from DAR.[81]

- Amy Robbins Ware (1877-1929), WWI veteran, author

- Flora Warren Seymour, writer, historian, author, first woman member of the Board of Indian Commissioners

- Florence Warfield Sillers, historian and socialite, founding member of the Mississippi Delta Chapter

- Jennie O. Starkey (ca. 1856 – 1918) was an American journalist

- Elizabeth Willisson Stephen (1856–1925), author[82]

- Fay Webb-Gardner, First Lady of North Carolina

- Agnes Wright Spring, member[42]

- Adelaide Cilley Waldron (1843–1909), author, editor, clubwoman

- Margaret Ray Wickens (1843–1918), national president of the Woman's Relief Corps

- Grace Steele Woodward (1899–1987), writer and historian

List of DAR presidents general

The presidents general of the society have been:[83][84]

Caroline Scott Harrison, First DAR President General

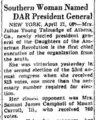

Caroline Scott Harrison, First DAR President General Southern Woman Named DAR President General

Southern Woman Named DAR President General Silver Arrow, the symbol of the Dillon administration in the form of a pin.

Silver Arrow, the symbol of the Dillon administration in the form of a pin.

| Number | President General | Years in office | State of membership |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caroline Scott Harrison , (Mrs. Benjamin) | 1890–1892, Died in office | Indiana |

| 1.5 | Mary Virginia Ellet Cabell , (Mrs. William D.) | 1892–1893, Vice President Presiding | Virginia |

| 2 | Letitia Green Stevenson , (Mrs. Adlai E.) | 1893–1895 | Illinois |

| 3 | Mary Parke McFerson Foster , (Mrs. John W.) | 1895–1896 | Indiana |

| 4 | Letitia Green Stevenson , (Mrs. Adlai E.) | 1896–1898 | Illinois |

| 5 | Mary Margaretta Fryer Manning , (Mrs. Daniel) | 1898–1899, & 1899–1901 | New York |

| 6 | Cornelia Cole Fairbanks , (Mrs. Charles W.) | 1901–1903, & 1903–1905 | Indiana |

| 7 | Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean , (Mrs. Donald) | 1905–1907, & 1907–1909 | New York |

| 8 | Julia Green Scott , (Mrs. Matthew T.) | 1909–1911, & 1911–1913 | Illinois |

| 9 | Daisy Allen Story , (Mrs. William Cumming) | 1913–1915, & 1915–1917 | New York |

| 10 | Sarah Elizabeth Mitchell Guernsey , (Mrs. George Thatcher) | 1917–1920 | Kansas |

| 11 | Anne Belle Rogers Minor , (Mrs. George Maynard) | 1920–1923 | Connecticut |

| 12 | Lora Haines Cook , (Mrs. Anthony Wayne) | 1923–1926 | Pennsylvania |

| 13 | Grace Lincoln Brosseau , (Mrs. Hall) | 1926–1929 | Connecticut |

| 14 | Edith Erwin Hobart , (Mrs. Lowell Fletcher) | 1929–1932 | Ohio |

| 15 | Edith Scott Magna , (Mrs. Russell William) | 1932–1935 | Massachusetts |

| 16 | Florence Hague Becker , (Mrs. William A.) | 1935–1938 | New Jersey |

| 17 | Sarah Corbin Robert , (Mrs. Henry Martyn Jr.) | 1938–1941 | Maryland |

| 18 | Helena R. Pouch , (Mrs. William H.) | 1941–1944 | New York |

| 19 | May Erwin Talmadge , (Mrs. Julius Young) | 1944–1947 | Georgia |

| 20 | Estella A. O'Byrne , (Mrs. Roscoe C.) | 1947–1950 | Indiana |

| 21 | Marguerite Courtright Patton , (Mrs. James B.) | 1950–1953 | Ohio |

| 22 | Gertrude Sprague Carraway | 1953–1956 | North Carolina |

| 23 | Allene Wilson Groves , (Mrs. Frederic A.) | 1956–1959 | Missouri |

| 24 | Doris Pike White,[85] (Mrs. Ashmead) | 1959–1962 | Maine |

| 25 | Marion Moncure Duncan , (Mrs. Robert V. H.) | 1962–1965 | Virginia |

| 26 | Adele Woodhouse Erb Sullivan , (Mrs. William Henry Jr.) | 1965–1968 | New York |

| 27 | Betty Newkirk Seimes , (Mrs. Erwin Frees) | 1968–1971 | Delaware |

| 28 | Eleanor Washington Spicer , (Mrs. Donald) | 1971–1974 | California |

| 29 | Sara Roddis Jones , (Mrs. Henry Stewart) | 1974–1975 | Wisconsin |

| 30 | Jane Farwell Smith , (Mrs. Wakelee Rawson) | 1975–1977 | Illinois |

| 31 | Jeannette Osborn Baylies , (Mrs. George Upham) | 1977–1980 | New York |

| 32 | Patricia Walton Shelby , (Mrs. Richard Denny) | 1980–1983 | Mississippi |

| 33 | Sarah McKelley King , (Mrs. Walter Hughey) | 1983–1986 | Tennessee |

| 34 | Ann Davison Duffie Fleck , (Mrs. Raymond Franklin) | 1986–1989 | Massachusetts |

| 35 | Marie Hirst Yochim , (Mrs. Eldred Martin) | 1989–1992 | Virginia |

| 36 | Wayne Garrison Blair , (Mrs. Donald Shattuck) | 1992–1995 | Ohio |

| 37 | Dorla Eaton Kemper , (Mrs. Charles Keil) | 1995–1998 | California |

| 38 | Georgane Ferguson Love (Easley) , (Mrs. Dale Kelly) | 1998–2001 | Mississippi |

| 39 | Linda Tinker Watkins* | 2001–2004 | Tennessee |

| 40 | Presley Merritt Wagoner | 2004–2007 | West Virginia |

| 41 | Linda Gist Calvin | 2007–2010 | California |

| 42 | Merry Ann T. Wright | 2010–2013 | New York |

| 43 | Lynn Forney Young | 2013–2016 | Texas |

| 44 | Ann Turner Dillon | 2016–2019 | Colorado |

| 45 | Denise Doring VanBuren | 2019–2022 | New York |

| 46 | Pamela Rouse Wright | 2022–2025 | Texas |

*Note: During the Watkins administration, the President General and other National Officers began to be referred to by their own first names, rather than their husbands'.

Honors

A memorial to the Daughters of the American Revolution's four founders at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated on April 17, 1929. It was sculpted by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a DAR member.[86][87]

See also

- The Hereditary Society Community of the United States of America

- Children of the American Revolution

- Colonial Dames of America

- The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America

- Old Stock Americans

- Society of the Cincinnati

- Sons of the American Revolution

- Sons of the Revolution

- Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War

- The United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada

- United States Daughters of 1812

References

- 1 2 3 "How to Join". Daughters of the American Revolution. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ↑ Continental Congress membership report

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution. (2013). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from library.eb.com

- ↑ Maslin Nir, Sarah (July 3, 2012). "For Daughters of the American Revolution, a New Chapter". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Plys, Kate (July 4, 1991). "I Had Luncheon With the DAR". Chicago Reader. Sun-Times Media. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ "The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum." Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum – Marian Anderson. N.p., n.d. Web. May 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. 1915. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ↑ Contributed (July 12, 2019). "DAR honors Real Daughters of the Revolutionary War buried in Redlands". Redlands News. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ↑ National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution 1991, p. 22.

- ↑ National Bylaws of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. pp. 26, 36.

- ↑ National Bylaws of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 12.

- ↑ "Daughters of the American Revolution: Did You Know?". Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ↑ Ed. Feller, Carolyn M. and Debora R. Cox (2016). Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History. p. 5.

- ↑ Gessner, Ingrid (2015). "Heroines of Health: Examining the Other Side of the "Splendid Little War"". European Journal of American Studies. 10–1, Special Issue: Women in the USA: 1–20 – via OpenEdition.

- ↑ "Feb 21, 1955 Issue | Texas Observer Print Archives". issues.texasobserver.org. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ↑ United States Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1962.

- 1 2 "DAR History". Daughters of the American Revolution. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ↑ VanBuren, Denise Doring (December 14, 2020). "A Productive Executive Session". DAR Blog.

- 1 2 "Forgotten Patriots Book". Daughters of the American Revolution.

- ↑ "DAR Genealogical Research Databases". services.dar.org.

- 1 2 3 Zurick, Maura (July 26, 2023). "Daughters of the American Revolution Members Quit Over Transgender Fears". Newsweek. Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ↑ Spears, Hunter (January 8, 2024). "When the DAR Said Trans Women Were Allowed, Controversy Ensued". Washingtonian. Catherine Merrill Williams. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ↑ "DAR Supported Schools". DAR. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Work of the Society: DAR Schools". DAR. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Literacy Promotion". DAR. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "American History Essay". DAR. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Scholarships". DAR. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ Beito, David (November 15, 2023). "Zora and Eleanor: Toward a Fuller Understanding of the First Lady's Civil Rights Legacy". Independent Institute.

- ↑ "Exhibit: Eleanor Roosevelt Letter". NARA. February 26, 1939. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ↑ Kennedy Center, "Biography of Marian Anderson" Archived January 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sandage, Scott (June 7, 1993). "Apologies for D.A.R. Racism Never End". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Karen Farmer" Archived December 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, American Libraries 39 (February 1978), p. 70; Negro Almanac, pp. 73,1431; Who's Who among Africans, 14th ed., p. 405.

- ↑ Stevens, William K. (December 28, 1977). "A Detroit Black Woman's Roots Lead to a Welcome in the D.A.R." The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 Kessler, Ronald (March 12, 1984). "Sponsors Claim Race Is Stumbling Block". The Washington Post. p. 1.

- ↑ Kessler, Ronald (April 18, 1984). "DAR Chief Says Black's Application Handled 'Inappropriately'". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 "Forgotten Patriots". Daughters of the American Revolution.

- ↑ American Spirit Magazine, Daughters of the American Revolution, January–February 2009, p. 4

- ↑ Hajela, Deepti (June 29, 2019). "Daughters of the American Revolution Welcomes First Black Woman, Wilhelmena Rhodes Kelly, to National Board". Black Christian News Network One. Associated Press. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ↑ "Kent State Stark – Kent State University". www.stark.kent.edu.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Dazzling Daughters, 1890–2004". Americana Collection exhibit. DAR. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ↑ "Walter Burdick Chapter: Gallery". Walter Burdick Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR). Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Binheim, Max; Elvin, Charles A (1928). Women of the West; a series of biographical sketches of living eminent women in the eleven western states of the United States of America. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1898). "WHAT WE ARE DOING AND CHAPTER WORK". Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. 13: 153. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1899). "MRS. CLARA BANCROFT BEATLEY. 9125". Lineage Book (Public domain ed.). The Society. p. 49. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ↑ Brockett, Hattie Nourse; Hatcher, Georgia Stockton (1898). Directory of the Chapters, Officers and Members (Public domain ed.). Washington, D.C.: Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 214. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ↑ Moss Scott, Rose (1929). "Pierre Menard". Daughters of the American Revolution. Illinois Printing Company. p. 109.

- ↑ Musser, Ashley; Dutton, Julie (February 11, 2016). "Illinois Women in Congress and General Assembly" (PDF). Springfield, Illinois: Illinois Legislative Research Unit. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Broughton, Alice Harper Willson | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Ancestral Register of the General Society, 1896". 1897.

- ↑ "Obituary, Annetta Rebecca Chipp. Died in Boise, Idaho, March 25, 1961". The Idaho Statesman. March 26, 1961. p. 34. Retrieved December 23, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1908). Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (Public domain ed.). Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 251. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ↑ Georgia. Department of Archives and History (1926). "Collier, Mrs. Margaret Wootten (Mrs. Bryan Wells)". Georgia Women of 1926. Georgia Department of Archives and History. p. 23. OCLC 25809880.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1905). The American Monthly Magazine. Vol. 28 (Public domain ed.). R.R. Bowker Company.

- ↑ Hunter, Ann Arnold, A Century of Service: The Story of the DAR, p. 63

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1900). Lineage Book. The Society. p. 213. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Foster, Mary Dillon (1924). "Wilma Anderson Gilman". Who's who Among Minnesota Women: A History of Woman's Work in Minnesota from Pioneer Days to Date, Told in Biographies, Memorials and Records of Organizations. Mary Dillon Foster. p. 120. Retrieved June 21, 2022 – via HathiTrust.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "GRABEEL, GENE". Richmond Times-Dispatch. February 15, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ↑ Revolution, Daughters of the American (1923). Lineage Book. The Society. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ↑ "Hoey, Margaret Elizabeth Gardner | NCpedia".

- ↑ Homan, Wayne. "The Woman Who Saved The Shrine". King of Prussia Historical Society. Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ "Patriots Visit Valley Forge: A Distinguished Party Inspects Historic Spots". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia Inquirer. November 18, 1891. p. 6.

- ↑ Fornance, Ellen (1917). "Prayer Desk Dedication – Washington Memorial Chapel". Google Books. Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ "Backstory of Washington's Headquarters". King of Prussia Historical Society. June 23, 2018.

- ↑ Stager, Henry J (1911). "Full Text of History of Centennial and Memorial Association of Valley Forge". Archive.org. U.S. NPS, LOC.

- ↑ Holstein, Anna Morris (1867). "Three Years In Field Hospitals Of The Army of The Potomac". Google Books. J.B. Lippincott, 1867.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1921). Lineage Book. The Society. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1919). Lineage Book. The Society. p. 138. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Rossiter: Poppy lady's legacy lives on". Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Death Takes Mrs. Minor in Waterford". Hartford Courant. October 25, 1947. p. 4. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Morse Funeral To Be in De Soto Tomorrow – 12 Jan 1948, Mon • Page 17". St. Louis Post-Dispatch: 17. 1948. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- 1 2 Johnson, Anne (1914). Notable women of St. Louis, 1914. St. Louis, Woodward. p. 188. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ The National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Volume 55, p. 299.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1917). "MRS. HESTER DORSEY RICHARDSON. 44351". Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (Public domain ed.). Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 141. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1901). Lineage Book. The Society. pp. 18–.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1924). "MRS. LURA EUGENIE BROWN SMITH. 68797". Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol. 68–69 (Public domain ed.). Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 286. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1897). "Mrs. Mary Perkins Bell Smith. 2066". Lineage Book of the Charter Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol. 3. Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 25. OCLC 25883579.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1900). "Mrs. Adaline Emerson Thompson. 11473". Lineage Book. Vol. 12 (Public domain ed.). The Society. pp. 180–81. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "POLITICS IN THE AIR; "DAUGHTERS" ALERT". Evening Star (Public domain ed.). April 18, 1909. p. 5. Retrieved August 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Eighteenth Continental Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Washington, D. C., April 19th to 24th, 1909, Continental Memorial Hall". The American Monthly Magazine (Public domain ed.). National Society. 35: 102. 1909. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ↑ "The Four Founders". Daughters of the American Revolution.

- ↑ "Maryly VanLeer Peck". Florida Women's Hall of Fame. Florida Commission on the Status of Women. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1912). Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol. 36 (Public domain ed.). Daughters of the American Revolution.

- ↑ DAR Handbook and National Bylaws (33rd ed.). Washington, D.C. 2020. p. 34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (2013). The Wide Blue Sash (2nd ed.). National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. ISBN 9781892237163.

- ↑ White, Doris Pike (April 1962). "The President General's Message". Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. 96 (4): 355.

- ↑ "Founders Memorial". Daughters of the American Revolution. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Daughters of the American Revolution, Founders statue at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney located in James M. Goode's Foggy Bottom area". Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Archives and Records Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Works cited

- National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (1991). Centennial History of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 1889–1989. Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 9781563110283.

Further reading

- Independent accounts

- Anderson, Peggy. The Daughters (1972)

- Bailey, Diana L. American Treasure: The Enduring Spirit of the DAR, Walsworth Publishing Company (2007)

- Julie Des Jardins, Women and the Historical Enterprise in America: Gender, Race, and the Politics of Memory, 1880–1945, University of North Carolina Press (2003)

- Strayer, Martha. The D.A.R.: An Informal History, Washington, DC. Public Affairs Press (1958) (critically reviewed by Gilbert Steiner as covering personalities but not politics, Review, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, v.320, "Highway Safety and Traffic Control" (Nov. 1958), pp. 148–49.)

- Wendt, Simon. The Daughters of the American Revolution and Patriotic Memory in the Twentieth Century (U Press of Florida, 2020) online review

- Sara Wallace Goodman (2020) "'Good American citizens': a text-as-data analysis of citizenship manuals for immigrants, 1921–1996." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

- DAR-related

- Hunter, Ann Arnold. A Century of Service: The Story of the DAR. Washington, DC: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (1991).

- Simkovich, Patricia Joy. Indomitable Spirit: The Life of Ellen Hardin Walworth, Washington, DC: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (2001). (The life story of Ellen Hardin Walworth, one of the NSDAR founders.)

- 125 Years of Devotion to America, Washington, DC: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. DAR publication that includes reflections, prayers and ceremonial excerpts to capture material about the DAR and its members' service.

External links

- American Patriotic Societies Directory list by US War Period(s) (AVSOPS.com)

- National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, Official website

- "DAR Historic Sites and Database", includes national map

- Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War, DAR, information about minority patriots

- Daughters of the American Revolution at Curlie

- Daughters of the American Revolution (David Reese Chapter) Collection (MUM00098), University of Mississippi

- "Daughters of the American Revolution Library", FamilySearch Research Wiki, for genealogists

- "Daughters of the American Revolution", image by Grant Wood

- "A Guide to the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Massanutton Chapter Records, 1885–2005" James Madison University's Massanutten Chapter, National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution Collection, 1885–2005

- Works by Daughters of the American Revolution. Nebraska chapter at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Daughters of the American Revolution. Pittsburgh chapter at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Daughters of the American Revolution at Internet Archive

- Second Oldest D.A.R. Chapter historical marker in Atlanta, Georgia

- Toaping Castle Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution records at the University of Maryland Libraries

- The American Revolution Institute